An interesting discovery can be made while studying the collection of interviews with Harmony Korine: in practically every interview he mentions one aspect of filmmaking, that not only practically characterizes his view on film and literature, but also exemplifies the connection between his oeuvre and the database–narrative ideas that drive this text. Never once expressing his realization about him repeating himself on this topic in every single interview, Korine keeps bringing up his views on the scene’s superiority over the plot[1]. He sometimes rationalizes this by explaining this ideology’s resemblance to the ideology of life in general, but also by how focusing on scenes relates to the implicit marketing pragmatics of movies and how, in fact, at the end of the day only singular scenes remain in a viewer’s memory after a visit to a cinema.

I find those ideas and the emphasis on the scenes as another a spot-on illustration to the “Database Cinema” theory[2]. It is important to think about the scenes of a Korine script like photographs, because after writing a voluminous database of those, the editing process becomes the process of selecting the best and putting them into the script like into a photobook. In a 2019 interview at the Gucci Hub in Milan[3], Korine admits to the usage of cue cards in the process of writing “Gummo”, to even stronger emphasize his prioritization of scenes.

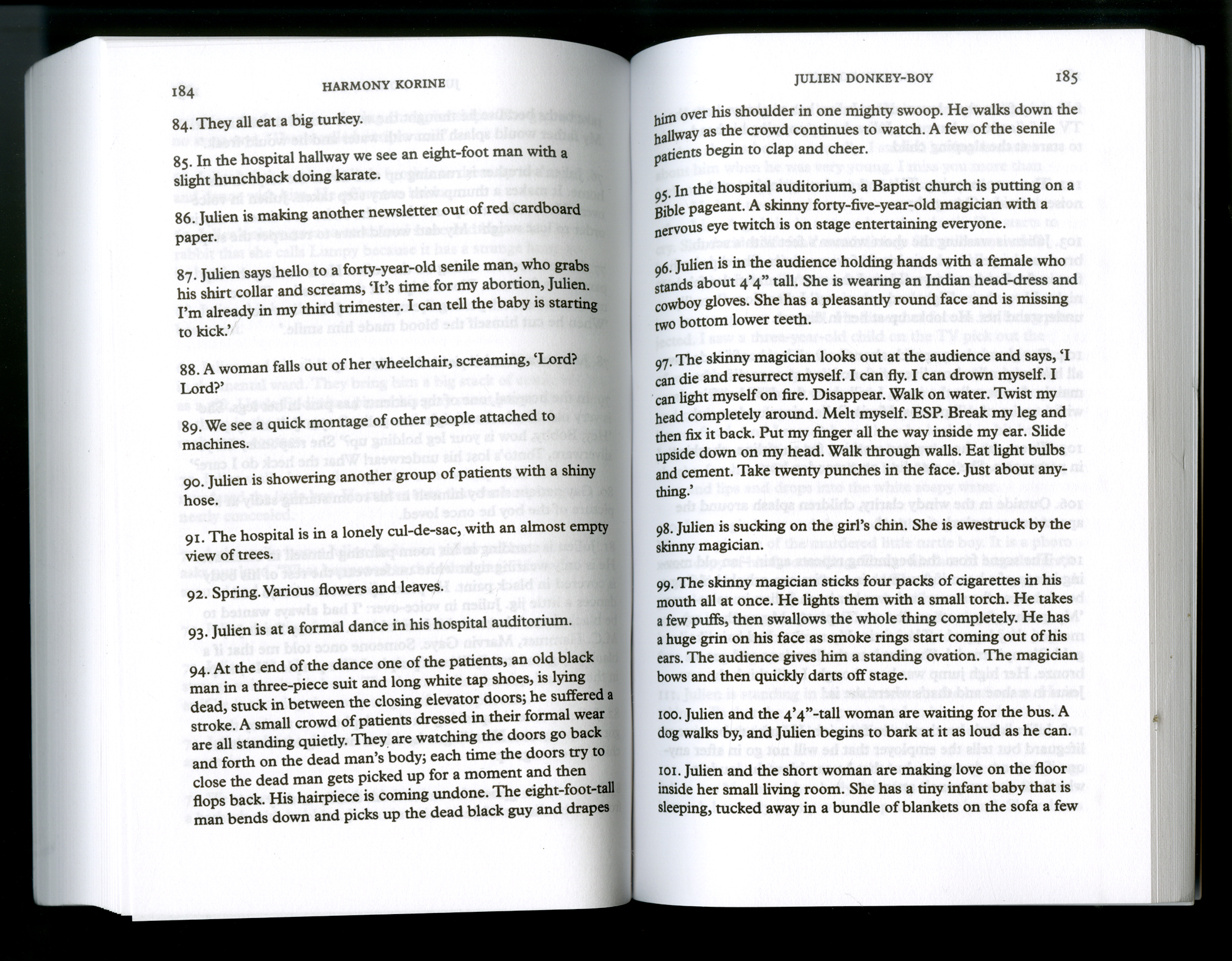

A striking example of the application of Korine’s scene-based approach can be found in the script for his 1999 feature film “julien donkey-boy”[4]. Uncovered only to those who buy the “Collected Screenplays 1” book, the “instruction” to the understanding of the script reads:

This is a non-traditional script design. The order in which the scenes are written should serve as a ver broad skeletal frame. I am only using them a as a guide which the story is hung upon. (…) The written scenes have no particular order.

In the same interview at the Gucci Hub, Korine opens up even more about his approach to filming/performing the pre-written scenes. Still on the topic of “Gummo”, he describes filming the same scenes many times in many arrangements and locations, therefore creating an even larger database and letting the narrative creation process happen during the editing and in the minds of the spectators. The alternative performances of the scenes that are instances of a database are related in absentia in the final cut of the film, so they only exist in the mind of the moviemaker and the viewer, if they are imagined. I consider this an interesting illustration of the existence of Manovich’s paradigmatic sets related in absentia and existing only implicitly.