One of the other illustrations to the database-oriented methods of representation can be found in Harmony Korine’s script of the never–produced movie “Jokes”[1]. The screenplay starts with a disclaimer about the its nontraditional nature and announces the database-like structure.

jokes is a separate undertaking, written in conjunction with the former. it is a movie in three parts. each chapter so to speak is based on a milton berle joke, usually a one-liner in the vein of henny youngman. basically i picked three separate jokes and embellished each one in order to stretch out a simple narrative of sorts. at the time i was watching all the alan clark films i could see and i was very much excited by his technique, his use of long flowing steady cam, no frills organic filmmaking. so i was inspired to approach each joke/chapter in a similar way, a return to a place i had never before felt any interest.

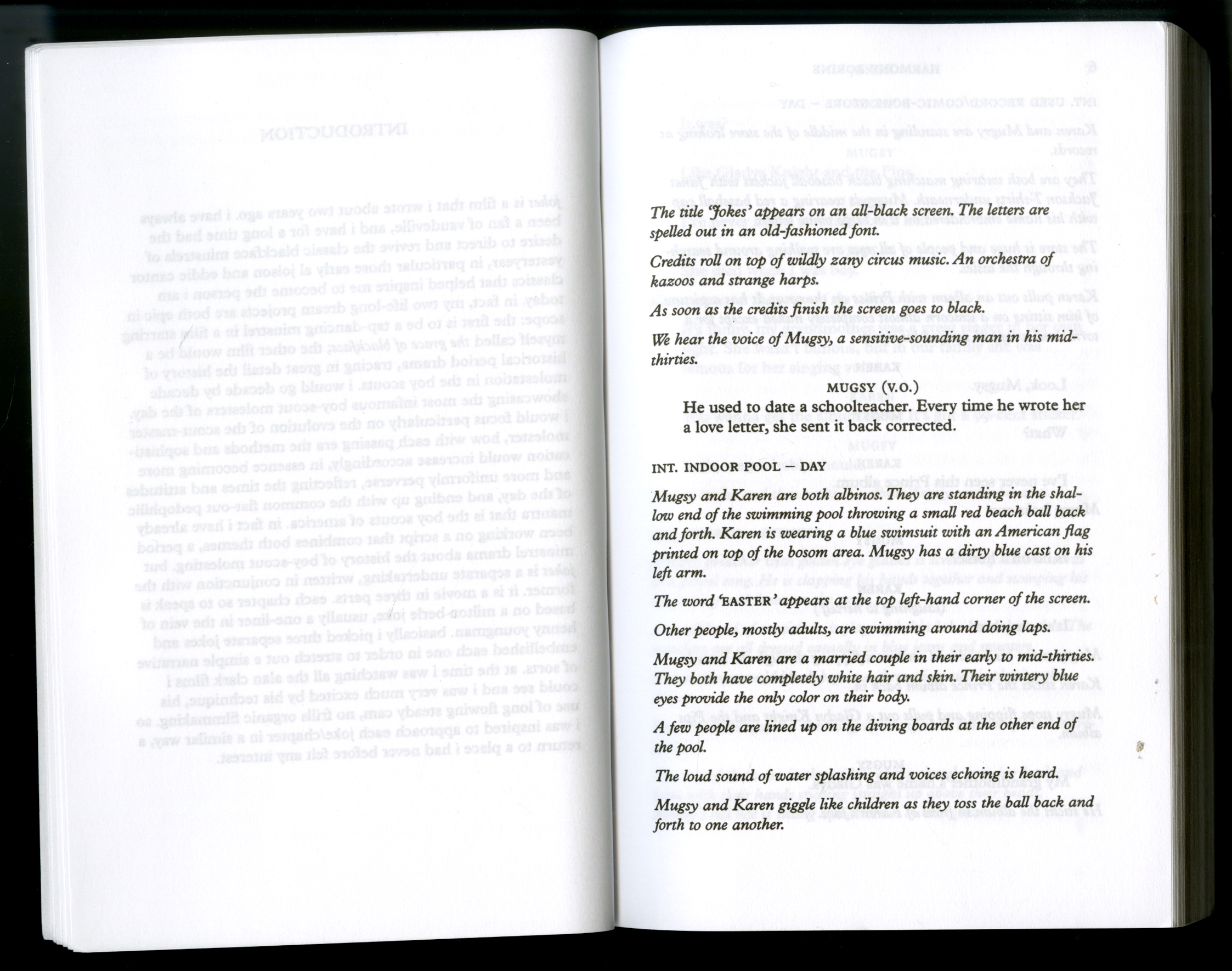

What follows is according to the introduction—a short script, of which every “chapter” begins with a joke told by the main character of the following story[FIG]. The stories: tautly constructed, highly imaginative and show his intuitive sense for emotion, tenderness, and of course the bizarre. The result: intriguing, thought-provoking and shocking journey leaving the viewer with more questions than answers. As a movie should and as life always does—claims Korine.

In this particular example, it’s interesting to think about the script as a translation of the narrative style of Henny Youngman's “one-liner” joke performances into a movie script and achieving a similar effect on the viewer. The fragmentation of the narrative creates tension and impedes the process of interpreting the story by the viewer. The more fragmented the structure and the more implicit the narrative, the receiving process gains in attentiveness and alertness. The “jokes” script reads in a shocking and convoluted manner and additionally gains even more complexity with the juxtaposition of the specific joke preceding the chapter and the content of it.