4. To index the external.

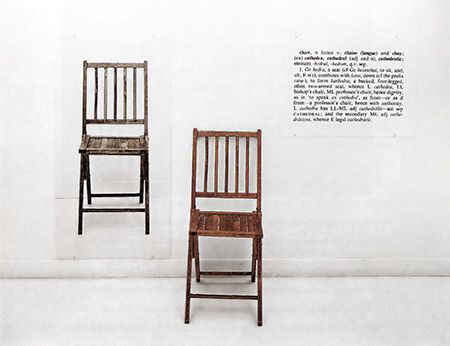

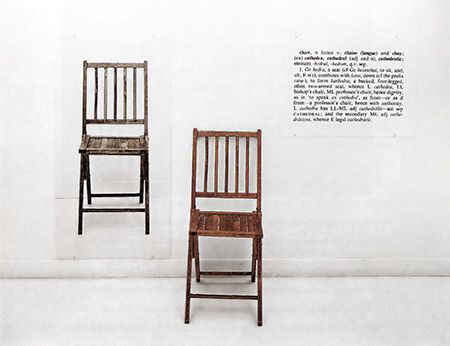

A frame is a border between two worlds, a separator between inside and outside, a binary divider between what is and what isn't. Humans (and other animals for that matter) recognise patterns and index the things we experience by comparing them to previous encounters, which –in primal terms– allows us to understand, process, and survive. Think of the importance of being able to tell food and danger apart in a cave(hu)man scenario. In this example, the frame is a border surrounding different conceptual boxes in our head. In his 1965 work entitled "One and three chairs" (fig. 9), Joseph Kosuth presents three embodiments of a chair: A chair, a photograph of that same chair, and a dictionary definition of a chair. With this work he starts a discourse about semantics and our relationship to external concepts.

But of course, we can also find more literal examples of borders. Humans have sectioned off territory with lines on maps, and borders on land, to indicate where one nation state ends and the other starts. We've subdivided geographic masses into regions according to the language, dialects, history, and traditions of those regions (fig. 10). But not all territories are (hu)manmade, a territory can also consist of a physiological limitation within an ecosystem. A fish and a frog that live in the same pond have different territories, simply because a frog is an amphibian and can go on land (fig. 11). But animal territories are not only defined by their physical capabilities. A 2013 documentary produced by the British television series "Horizon" entitled "The Secret Life of the Cat", follows 50 domestic cats by equipping them with cameras and GPS trackers (fig. 12) 5. In this documentary we discover that cats have much more intricate territorial dynamics and habits than previously thought.

A frame is not only the border between worlds, but it also dictates the laws and hierarchies that govern these worlds, and not only the bureaucratic judicial laws of countries. Imagine, for example, the top view of an apartment layout. The apartment is divided into multiple rooms by its walls, these could be seen as frames of the house. Each room (or section) has different rules and expectations of what they are "supposed" to look like, what activities take place in them etc. These expectations are socially constructed concepts that live in our heads.

Let's take a bathroom for instance. we might not have seen every bathroom ever, but as soon as we spot a toilet bowl, a sink, and perhaps some square tiles we know what we're dealing with. We also recognise the nuances these attributes carry. If we see a toilet bowl discarded in the street or on display in a store, we know that they are not intended for use. But now imagine if we didn't have this pattern-recognising system in our brain, and every time we would visit a unfamiliar bathroom, we would have to rediscover how to do our business. It would be as if you're on a holiday in a country with foreign bathroom traditions, and you haven't developed a successful technique yet (fig. 13).

It is important to emphasize that this type of pattern-recognition is based on previous input. This means that the resulting conclusions should not be regarded as any sort of absolute truth. This of course, becomes especially relevant when dealing with artificial intelligence, which is completely based on pattern-recognition and data input and therefore susceptible to pre-existing biases.

In a conversation with Femke Snelting and Jara Rocha, following a screening of her work "The Fragility of Life", Simone Niquille compares anthropometric efforts to "...an attempt to translate the human body into numbers. Be it for the sake of comparison, efficiency, policing."6. In Allan Sekula's article "The body and the archive" he argues against these types of practices by saying that "The photographic archive's components are not conventional lexical units, but rather are subject to the circumstantial character of all that is photographable."7 and that therefore they should not be regarded as empirical units of measurement.

4. To index the external.

A frame is a border between two worlds, a separator between inside and outside, a binary divider between what is and what isn't. Humans (and other animals for that matter) recognise patterns and index the things we experience by comparing them to previous encounters, which –in primal terms– allows us to understand, process, and survive. Think of the importance of being able to tell food and danger apart in a cave(hu)man scenario. In this example, the frame is a border surrounding different conceptual boxes in our head. In his 1965 work entitled "One and three chairs" (fig. 9), Joseph Kosuth presents three embodiments of a chair: A chair, a photograph of that same chair, and a dictionary definition of a chair. With this work he starts a discourse about semantics and our relationship to external concepts.

But of course, we can also find more literal examples of borders. Humans have sectioned off territory with lines on maps, and borders on land, to indicate where one nation state ends and the other starts. We've subdivided geographic masses into regions according to the language, dialects, history, and traditions of those regions (fig. 10). But not all territories are (hu)manmade, a territory can also consist of a physiological limitation within an ecosystem. A fish and a frog that live in the same pond have different territories, simply because a frog is an amphibian and can go on land (fig. 11). But animal territories are not only defined by their physical capabilities. A 2013 documentary produced by the British television series "Horizon" entitled "The Secret Life of the Cat", follows 50 domestic cats by equipping them with cameras and GPS trackers (fig. 12) 5. In this documentary we discover that cats have much more intricate territorial dynamics and habits than previously thought.

A frame is not only the border between worlds, but it also dictates the laws and hierarchies that govern these worlds, and not only the bureaucratic judicial laws of countries. Imagine, for example, the top view of an apartment layout. The apartment is divided into multiple rooms by its walls, these could be seen as frames of the house. Each room (or section) has different rules and expectations of what they are "supposed" to look like, what activities take place in them etc. These expectations are socially constructed concepts that live in our heads.

Let's take a bathroom for instance. we might not have seen every bathroom ever, but as soon as we spot a toilet bowl, a sink, and perhaps some square tiles we know what we're dealing with. We also recognise the nuances these attributes carry. If we see a toilet bowl discarded in the street or on display in a store, we know that they are not intended for use. But now imagine if we didn't have this pattern-recognising system in our brain, and every time we would visit a unfamiliar bathroom, we would have to rediscover how to do our business. It would be as if you're on a holiday in a country with foreign bathroom traditions, and you haven't developed a successful technique yet (fig. 13).

It is important to emphasize that this type of pattern-recognition is based on previous input. This means that the resulting conclusions should not be regarded as any sort of absolute truth. This of course, becomes especially relevant when dealing with artificial intelligence, which is completely based on pattern-recognition and data input and therefore susceptible to pre-existing biases.

In a conversation with Femke Snelting and Jara Rocha, following a screening of her work "The Fragility of Life", Simone Niquille compares anthropometric efforts to "...an attempt to translate the human body into numbers. Be it for the sake of comparison, efficiency, policing."6. In Allan Sekula's article "The body and the archive" he argues against these types of practices by saying that "The photographic archive's components are not conventional lexical units, but rather are subject to the circumstantial character of all that is photographable."7 and that therefore they should not be regarded as empirical units of measurement.

4. To index the external.

A frame is a border between two worlds, a separator between inside and outside, a binary divider between what is and what isn't. Humans (and other animals for that matter) recognise patterns and index the things we experience by comparing them to previous encounters, which –in primal terms– allows us to understand, process, and survive. Think of the importance of being able to tell food and danger apart in a cave(hu)man scenario. In this example, the frame is a border surrounding different conceptual boxes in our head. In his 1965 work entitled "One and three chairs" (fig. 9), Joseph Kosuth presents three embodiments of a chair: A chair, a photograph of that same chair, and a dictionary definition of a chair. With this work he starts a discourse about semantics and our relationship to external concepts.

But of course, we can also find more literal examples of borders. Humans have sectioned off territory with lines on maps, and borders on land, to indicate where one nation state ends and the other starts. We've subdivided geographic masses into regions according to the language, dialects, history, and traditions of those regions (fig. 10). But not all territories are (hu)manmade, a territory can also consist of a physiological limitation within an ecosystem. A fish and a frog that live in the same pond have different territories, simply because a frog is an amphibian and can go on land (fig. 11). But animal territories are not only defined by their physical capabilities. A 2013 documentary produced by the British television series "Horizon" entitled "The Secret Life of the Cat", follows 50 domestic cats by equipping them with cameras and GPS trackers (fig. 12) 5. In this documentary we discover that cats have much more intricate territorial dynamics and habits than previously thought.

A frame is not only the border between worlds, but it also dictates the laws and hierarchies that govern these worlds, and not only the bureaucratic judicial laws of countries. Imagine, for example, the top view of an apartment layout. The apartment is divided into multiple rooms by its walls, these could be seen as frames of the house. Each room (or section) has different rules and expectations of what they are "supposed" to look like, what activities take place in them etc. These expectations are socially constructed concepts that live in our heads.

Let's take a bathroom for instance. we might not have seen every bathroom ever, but as soon as we spot a toilet bowl, a sink, and perhaps some square tiles we know what we're dealing with. We also recognise the nuances these attributes carry. If we see a toilet bowl discarded in the street or on display in a store, we know that they are not intended for use. But now imagine if we didn't have this pattern-recognising system in our brain, and every time we would visit a unfamiliar bathroom, we would have to rediscover how to do our business. It would be as if you're on a holiday in a country with foreign bathroom traditions, and you haven't developed a successful technique yet (fig. 13).

It is important to emphasize that this type of pattern-recognition is based on previous input. This means that the resulting conclusions should not be regarded as any sort of absolute truth. This of course, becomes especially relevant when dealing with artificial intelligence, which is completely based on pattern-recognition and data input and therefore susceptible to pre-existing biases.

In a conversation with Femke Snelting and Jara Rocha, following a screening of her work "The Fragility of Life", Simone Niquille compares anthropometric efforts to "...an attempt to translate the human body into numbers. Be it for the sake of comparison, efficiency, policing."6. In Allan Sekula's article "The body and the archive" he argues against these types of practices by saying that "The photographic archive's components are not conventional lexical units, but rather are subject to the circumstantial character of all that is photographable."7 and that therefore they should not be regarded as empirical units of measurement.

“Secret Life of the Cat: The Science of Tracking Our Pets,” June 12, 2013↩︎

Simone Niquille, “The Fragility of Life,” Nieuwe Instituut (blog), July 13, 2017↩︎

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (1986): 3–64↩︎

4. To index the external.

A frame is a border between two worlds, a separator between inside and outside, a binary divider between what is and what isn't. Humans (and other animals for that matter) recognise patterns and index the things we experience by comparing them to previous encounters, which –in primal terms– allows us to understand, process, and survive. Think of the importance of being able to tell food and danger apart in a cave(hu)man scenario. In this example, the frame is a border surrounding different conceptual boxes in our head. In his 1965 work entitled "One and three chairs" (fig. 9), Joseph Kosuth presents three embodiments of a chair: A chair, a photograph of that same chair, and a dictionary definition of a chair. With this work he starts a discourse about semantics and our relationship to external concepts.

But of course, we can also find more literal examples of borders. Humans have sectioned off territory with lines on maps, and borders on land, to indicate where one nation state ends and the other starts. We've subdivided geographic masses into regions according to the language, dialects, history, and traditions of those regions (fig. 10). But not all territories are (hu)manmade, a territory can also consist of a physiological limitation within an ecosystem. A fish and a frog that live in the same pond have different territories, simply because a frog is an amphibian and can go on land (fig. 11). But animal territories are not only defined by their physical capabilities. A 2013 documentary produced by the British television series "Horizon" entitled "The Secret Life of the Cat", follows 50 domestic cats by equipping them with cameras and GPS trackers (fig. 12) 5. In this documentary we discover that cats have much more intricate territorial dynamics and habits than previously thought.

A frame is not only the border between worlds, but it also dictates the laws and hierarchies that govern these worlds, and not only the bureaucratic judicial laws of countries. Imagine, for example, the top view of an apartment layout. The apartment is divided into multiple rooms by its walls, these could be seen as frames of the house. Each room (or section) has different rules and expectations of what they are "supposed" to look like, what activities take place in them etc. These expectations are socially constructed concepts that live in our heads.

Let's take a bathroom for instance. we might not have seen every bathroom ever, but as soon as we spot a toilet bowl, a sink, and perhaps some square tiles we know what we're dealing with. We also recognise the nuances these attributes carry. If we see a toilet bowl discarded in the street or on display in a store, we know that they are not intended for use. But now imagine if we didn't have this pattern-recognising system in our brain, and every time we would visit a unfamiliar bathroom, we would have to rediscover how to do our business. It would be as if you're on a holiday in a country with foreign bathroom traditions, and you haven't developed a successful technique yet (fig. 13).

It is important to emphasize that this type of pattern-recognition is based on previous input. This means that the resulting conclusions should not be regarded as any sort of absolute truth. This of course, becomes especially relevant when dealing with artificial intelligence, which is completely based on pattern-recognition and data input and therefore susceptible to pre-existing biases.

In a conversation with Femke Snelting and Jara Rocha, following a screening of her work "The Fragility of Life", Simone Niquille compares anthropometric efforts to "...an attempt to translate the human body into numbers. Be it for the sake of comparison, efficiency, policing."6. In Allan Sekula's article "The body and the archive" he argues against these types of practices by saying that "The photographic archive's components are not conventional lexical units, but rather are subject to the circumstantial character of all that is photographable."7 and that therefore they should not be regarded as empirical units of measurement.

“Secret Life of the Cat: The Science of Tracking Our Pets,” June 12, 2013↩︎

Simone Niquille, “The Fragility of Life,” Nieuwe Instituut (blog), July 13, 2017↩︎

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (1986): 3–64↩︎