3. To endow with importance

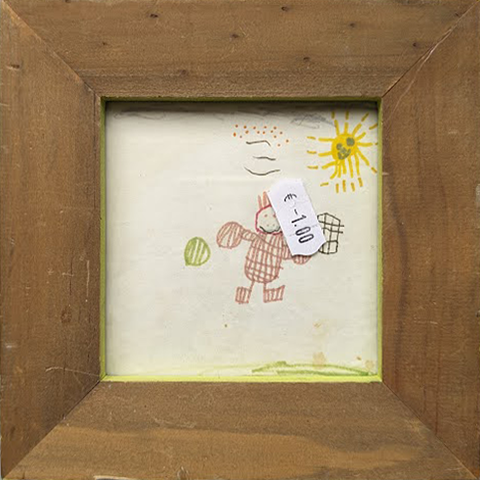

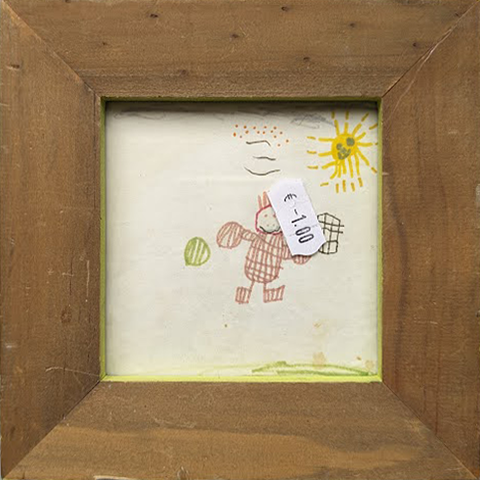

As we just concluded, each act of framing is the result of a curation (though not necessarily deliberate or conscious). Because of this, we can assume that whatever is framed holds some degree of importance to the framer. A grandparent framing a drawing made by their grandchild is an obvious example (fig. 6). The grandparent probably won't care much about the artistic value of the drawing because it is the grandchild that is important to them.

With this logic, we can look at the act of framing as a ritual that bestows a certain validity and authority over the framed. A lacklustre drawing that is hung on the refrigerator may be ugly, but the mere fact that it was put on display is a statement that tells anyone who sees it, that the drawing is important to the fridge-owner. Even though there was not literal frame in this example, the act of putting an item on display, can be regarded as framing. Making it no different than an expensive gilded frame in a museum.

If we look at a frame beyond its physical container as the institution it represents, we start to see how the credibility of the author is transmitted to the contents by the used medium. Think of the instantly recognisable blue envelopes that have become synonymous with the Dutch tax administration (fig. 7). If these bills were instead handwritten in coloured pencils, covered in sparkly stickers, and full of grammatical errors, we would question their legitimacy and be hesitant to pay them.

But the opposite is also true. A veil of credibility and truthfulness can be created by replicating or appropriating certain institutional aesthetics. A malicious example of this is phishing emails, pretending to be a legitimate service to scam unwary victims. Another, more light-hearted example happened in 2017, when twitch-streamer A.J. Lester illegally broadcasted a pay-per-view UFC fight by holding a gaming controller and pretending to be playing a game, instead of watching a live event4 (fig. 8).

Owen S. Good, “UFC Pay-per-View Streamed on Twitch by a Guy Pretending It Was a Video Game,” n.d.↩︎

3. To endow with importance

As we just concluded, each act of framing is the result of a curation (though not necessarily deliberate or conscious). Because of this, we can assume that whatever is framed holds some degree of importance to the framer. A grandparent framing a drawing made by their grandchild is an obvious example (fig. 6). The grandparent probably won't care much about the artistic value of the drawing because it is the grandchild that is important to them.

With this logic, we can look at the act of framing as a ritual that bestows a certain validity and authority over the framed. A lacklustre drawing that is hung on the refrigerator may be ugly, but the mere fact that it was put on display is a statement that tells anyone who sees it, that the drawing is important to the fridge-owner. Even though there was not literal frame in this example, the act of putting an item on display, can be regarded as framing. Making it no different than an expensive gilded frame in a museum.

If we look at a frame beyond its physical container as the institution it represents, we start to see how the credibility of the author is transmitted to the contents by the used medium. Think of the instantly recognisable blue envelopes that have become synonymous with the Dutch tax administration (fig. 7). If these bills were instead handwritten in coloured pencils, covered in sparkly stickers, and full of grammatical errors, we would question their legitimacy and be hesitant to pay them.

But the opposite is also true. A veil of credibility and truthfulness can be created by replicating or appropriating certain institutional aesthetics. A malicious example of this is phishing emails, pretending to be a legitimate service to scam unwary victims. Another, more light-hearted example happened in 2017, when twitch-streamer A.J. Lester illegally broadcasted a pay-per-view UFC fight by holding a gaming controller and pretending to be playing a game, instead of watching a live event4 (fig. 8).

Owen S. Good, “UFC Pay-per-View Streamed on Twitch by a Guy Pretending It Was a Video Game,” n.d.↩︎

3. To endow with importance

As we just concluded, each act of framing is the result of a curation (though not necessarily deliberate or conscious). Because of this, we can assume that whatever is framed holds some degree of importance to the framer. A grandparent framing a drawing made by their grandchild is an obvious example (fig. 6). The grandparent probably won't care much about the artistic value of the drawing because it is the grandchild that is important to them.

With this logic, we can look at the act of framing as a ritual that bestows a certain validity and authority over the framed. A lacklustre drawing that is hung on the refrigerator may be ugly, but the mere fact that it was put on display is a statement that tells anyone who sees it, that the drawing is important to the fridge-owner. Even though there was not literal frame in this example, the act of putting an item on display, can be regarded as framing. Making it no different than an expensive gilded frame in a museum.

If we look at a frame beyond its physical container as the institution it represents, we start to see how the credibility of the author is transmitted to the contents by the used medium. Think of the instantly recognisable blue envelopes that have become synonymous with the Dutch tax administration (fig. 7). If these bills were instead handwritten in coloured pencils, covered in sparkly stickers, and full of grammatical errors, we would question their legitimacy and be hesitant to pay them.

But the opposite is also true. A veil of credibility and truthfulness can be created by replicating or appropriating certain institutional aesthetics. A malicious example of this is phishing emails, pretending to be a legitimate service to scam unwary victims. Another, more light-hearted example happened in 2017, when twitch-streamer A.J. Lester illegally broadcasted a pay-per-view UFC fight by holding a gaming controller and pretending to be playing a game, instead of watching a live event4 (fig. 8).

Owen S. Good, “UFC Pay-per-View Streamed on Twitch by a Guy Pretending It Was a Video Game,” n.d.↩︎

3. To endow with importance

As we just concluded, each act of framing is the result of a curation (though not necessarily deliberate or conscious). Because of this, we can assume that whatever is framed holds some degree of importance to the framer. A grandparent framing a drawing made by their grandchild is an obvious example (fig. 6). The grandparent probably won't care much about the artistic value of the drawing because it is the grandchild that is important to them.

With this logic, we can look at the act of framing as a ritual that bestows a certain validity and authority over the framed. A lacklustre drawing that is hung on the refrigerator may be ugly, but the mere fact that it was put on display is a statement that tells anyone who sees it, that the drawing is important to the fridge-owner. Even though there was not literal frame in this example, the act of putting an item on display, can be regarded as framing. Making it no different than an expensive gilded frame in a museum.

If we look at a frame beyond its physical container as the institution it represents, we start to see how the credibility of the author is transmitted to the contents by the used medium. Think of the instantly recognisable blue envelopes that have become synonymous with the Dutch tax administration (fig. 7). If these bills were instead handwritten in coloured pencils, covered in sparkly stickers, and full of grammatical errors, we would question their legitimacy and be hesitant to pay them.

But the opposite is also true. A veil of credibility and truthfulness can be created by replicating or appropriating certain institutional aesthetics. A malicious example of this is phishing emails, pretending to be a legitimate service to scam unwary victims. Another, more light-hearted example happened in 2017, when twitch-streamer A.J. Lester illegally broadcasted a pay-per-view UFC fight by holding a gaming controller and pretending to be playing a game, instead of watching a live event4 (fig. 8).

Owen S. Good, “UFC Pay-per-View Streamed on Twitch by a Guy Pretending It Was a Video Game,” n.d.↩︎