F**** the system (Frame the system)

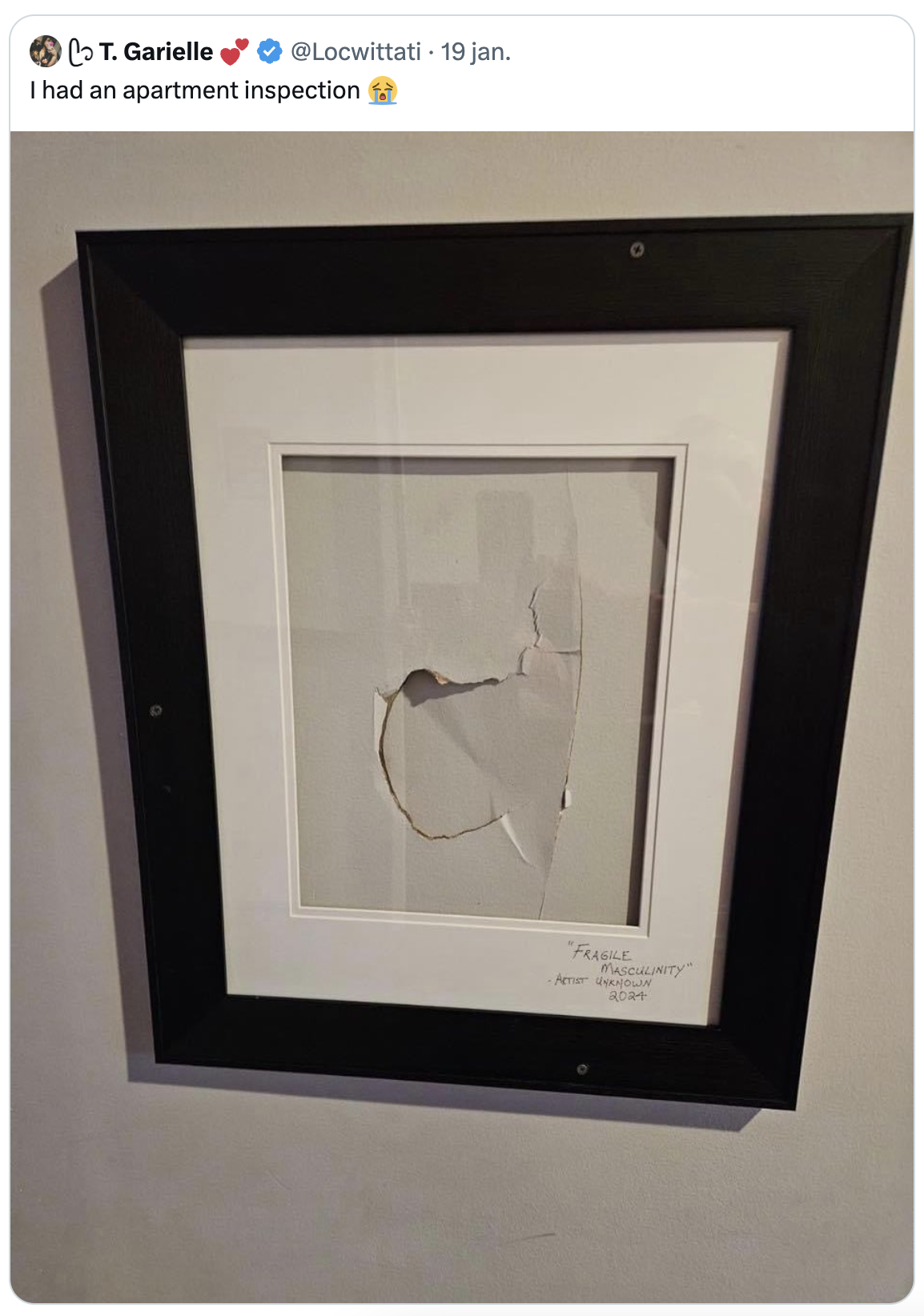

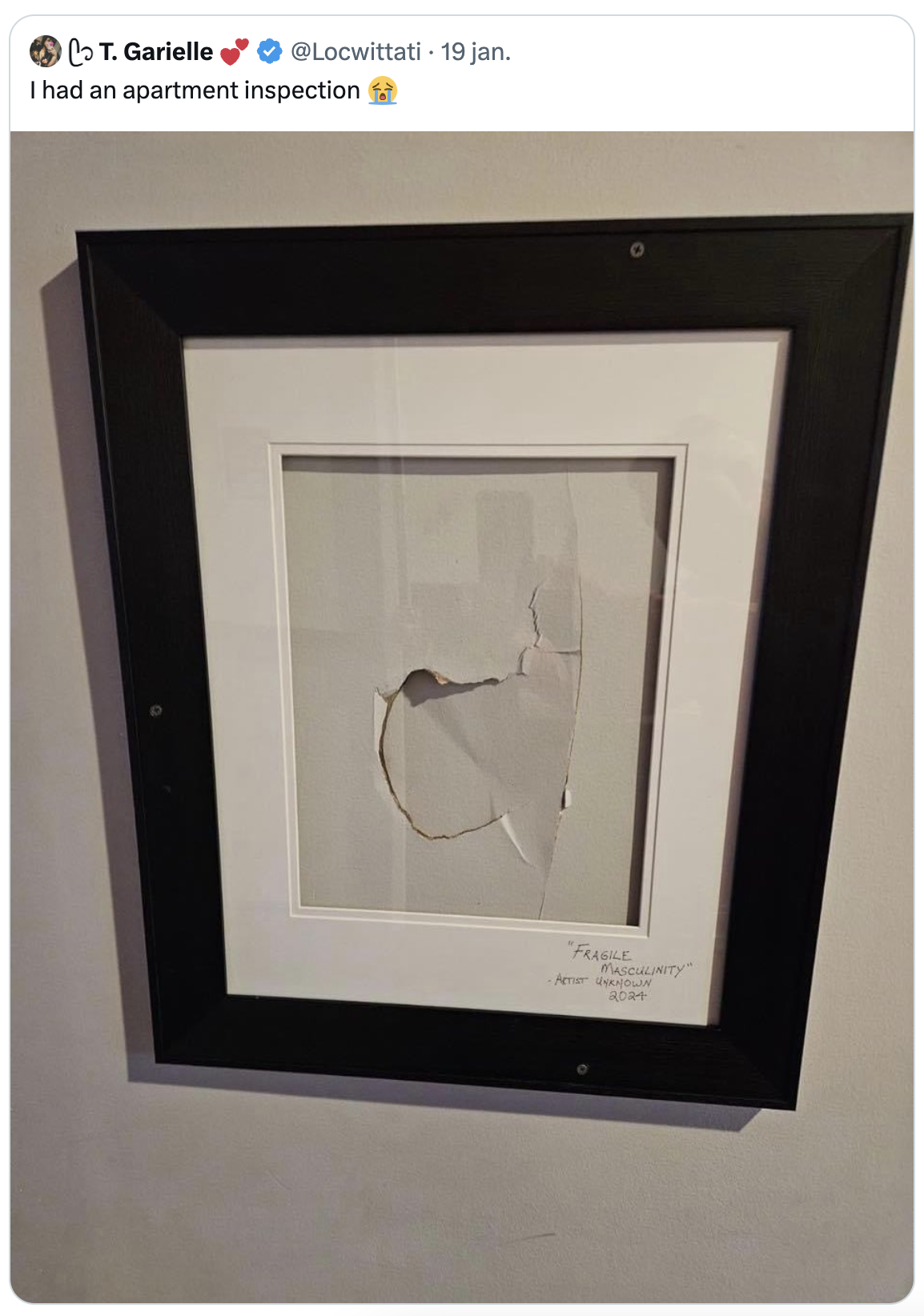

On January 24th, 2024, twitter user @Locwittati posted an image of a wall with a hole in it, covered up by a picture frame, to make it look like the damaged drywall was instead part of an artwork (fig. 25). The tweet was captioned: "I had an apartment inspection "15. In the KABK men's bathroom in the graphic design department, the walls are completely covered in graffiti tags, but among them is a small empty wooding picture frame, placed on top of some deep bathroom ponderings and inspirational quotes. On top of the frame somebody wrote "Does art make the frame or the frame makes art?" (fig. 26). And though both references might seem a bit silly, they open a discourse about the rigid, formal traditions and expectations within art. And while discussing these norms we must also mention Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), a Dada sculpture that challenged those same conventions (fig. 27). (There is some discourse about whether Duchamp was the creator of this work, or if it should be attributed to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven16).

Today, a popular form of visual expression takes place on trashcans, electricity boxes, traffic lights, and other urban furniture (fig. 28, fig. 29). We find all of these covered in graffiti and stickers. Most, if not all of these types of urban ornamentation would be considered vandalism by the government. But, these same urban items are often fitted with a reusable frame, that serves as a designated advertisement spot (fig. 30). In her work, Swedish artist Klara Liden (1979) recontextualizes these pieces of urban furniture by taking them out of their original context and presenting them in an exhibition (fig. 31). Her work is described as "marked by an enduring exploration of the physical and psychological bounds of the spaces – both public and private – we inhabit"17. When I see her work, I can't help but be reminded of the Fountain, because of the way her work highlights the mundane and creates a platform for more informal forms of visual media. Something about juxtaposing the graffiti and stickers –which will always be an underdog to regulated and institutional forms of media– with the "formal" context of a gallery, just feels so right.

F**** the system (Frame the system)

On January 24th, 2024, twitter user @Locwittati posted an image of a wall with a hole in it, covered up by a picture frame, to make it look like the damaged drywall was instead part of an artwork (fig. 25). The tweet was captioned: "I had an apartment inspection "15. In the KABK men's bathroom in the graphic design department, the walls are completely covered in graffiti tags, but among them is a small empty wooding picture frame, placed on top of some deep bathroom ponderings and inspirational quotes. On top of the frame somebody wrote "Does art make the frame or the frame makes art?" (fig. 26). And though both references might seem a bit silly, they open a discourse about the rigid, formal traditions and expectations within art. And while discussing these norms we must also mention Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), a Dada sculpture that challenged those same conventions (fig. 27). (There is some discourse about whether Duchamp was the creator of this work, or if it should be attributed to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven16).

Today, a popular form of visual expression takes place on trashcans, electricity boxes, traffic lights, and other urban furniture (fig. 28, fig. 29). We find all of these covered in graffiti and stickers. Most, if not all of these types of urban ornamentation would be considered vandalism by the government. But, these same urban items are often fitted with a reusable frame, that serves as a designated advertisement spot (fig. 30). In her work, Swedish artist Klara Liden (1979) recontextualizes these pieces of urban furniture by taking them out of their original context and presenting them in an exhibition (fig. 31). Her work is described as "marked by an enduring exploration of the physical and psychological bounds of the spaces – both public and private – we inhabit"17. When I see her work, I can't help but be reminded of the Fountain, because of the way her work highlights the mundane and creates a platform for more informal forms of visual media. Something about juxtaposing the graffiti and stickers –which will always be an underdog to regulated and institutional forms of media– with the "formal" context of a gallery, just feels so right.

F**** the system (Frame the system)

On January 24th, 2024, twitter user @Locwittati posted an image of a wall with a hole in it, covered up by a picture frame, to make it look like the damaged drywall was instead part of an artwork (fig. 25). The tweet was captioned: "I had an apartment inspection "15. In the KABK men's bathroom in the graphic design department, the walls are completely covered in graffiti tags, but among them is a small empty wooding picture frame, placed on top of some deep bathroom ponderings and inspirational quotes. On top of the frame somebody wrote "Does art make the frame or the frame makes art?" (fig. 26). And though both references might seem a bit silly, they open a discourse about the rigid, formal traditions and expectations within art. And while discussing these norms we must also mention Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), a Dada sculpture that challenged those same conventions (fig. 27). (There is some discourse about whether Duchamp was the creator of this work, or if it should be attributed to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven16).

Today, a popular form of visual expression takes place on trashcans, electricity boxes, traffic lights, and other urban furniture (fig. 28, fig. 29). We find all of these covered in graffiti and stickers. Most, if not all of these types of urban ornamentation would be considered vandalism by the government. But, these same urban items are often fitted with a reusable frame, that serves as a designated advertisement spot (fig. 30). In her work, Swedish artist Klara Liden (1979) recontextualizes these pieces of urban furniture by taking them out of their original context and presenting them in an exhibition (fig. 31). Her work is described as "marked by an enduring exploration of the physical and psychological bounds of the spaces – both public and private – we inhabit"17. When I see her work, I can't help but be reminded of the Fountain, because of the way her work highlights the mundane and creates a platform for more informal forms of visual media. Something about juxtaposing the graffiti and stickers –which will always be an underdog to regulated and institutional forms of media– with the "formal" context of a gallery, just feels so right.

@Locwittati, Twitter, January 24, 2024↩︎

Richard Whiddington, Did Duchamp Steal Credit for ‘The Fountain’ from a Woman Artist? (blog), October 25, 2023↩︎

Klara Liden, Sadie Coles HQ, February 22, 2024↩︎

F**** the system (Frame the system)

On January 24th, 2024, twitter user @Locwittati posted an image of a wall with a hole in it, covered up by a picture frame, to make it look like the damaged drywall was instead part of an artwork (fig. 25). The tweet was captioned: "I had an apartment inspection "15. In the KABK men's bathroom in the graphic design department, the walls are completely covered in graffiti tags, but among them is a small empty wooding picture frame, placed on top of some deep bathroom ponderings and inspirational quotes. On top of the frame somebody wrote "Does art make the frame or the frame makes art?" (fig. 26). And though both references might seem a bit silly, they open a discourse about the rigid, formal traditions and expectations within art. And while discussing these norms we must also mention Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), a Dada sculpture that challenged those same conventions (fig. 27). (There is some discourse about whether Duchamp was the creator of this work, or if it should be attributed to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven16).

Today, a popular form of visual expression takes place on trashcans, electricity boxes, traffic lights, and other urban furniture (fig. 28, fig. 29). We find all of these covered in graffiti and stickers. Most, if not all of these types of urban ornamentation would be considered vandalism by the government. But, these same urban items are often fitted with a reusable frame, that serves as a designated advertisement spot (fig. 30). In her work, Swedish artist Klara Liden (1979) recontextualizes these pieces of urban furniture by taking them out of their original context and presenting them in an exhibition (fig. 31). Her work is described as "marked by an enduring exploration of the physical and psychological bounds of the spaces – both public and private – we inhabit"17. When I see her work, I can't help but be reminded of the Fountain, because of the way her work highlights the mundane and creates a platform for more informal forms of visual media. Something about juxtaposing the graffiti and stickers –which will always be an underdog to regulated and institutional forms of media– with the "formal" context of a gallery, just feels so right.

@Locwittati, Twitter, January 24, 2024↩︎

Richard Whiddington, Did Duchamp Steal Credit for ‘The Fountain’ from a Woman Artist? (blog), October 25, 2023↩︎

Klara Liden, Sadie Coles HQ, February 22, 2024↩︎