Frames in illuminated parchment and the Kelmscott Press

We see another interesting usage of frames in medieval books, which follow a rich tradition of ornamental borders and illustrated margins. Because these books were made long before the invention of the printing press, each specimen was crafted through countless hours of meticulous and precise hand labour. This job, tasked to monks in a monastery, was very difficult and often took place under less-than-ideal circumstances. We know this because some scribes wrote little complaints in the books. An example of such complaints is "Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides,"11.

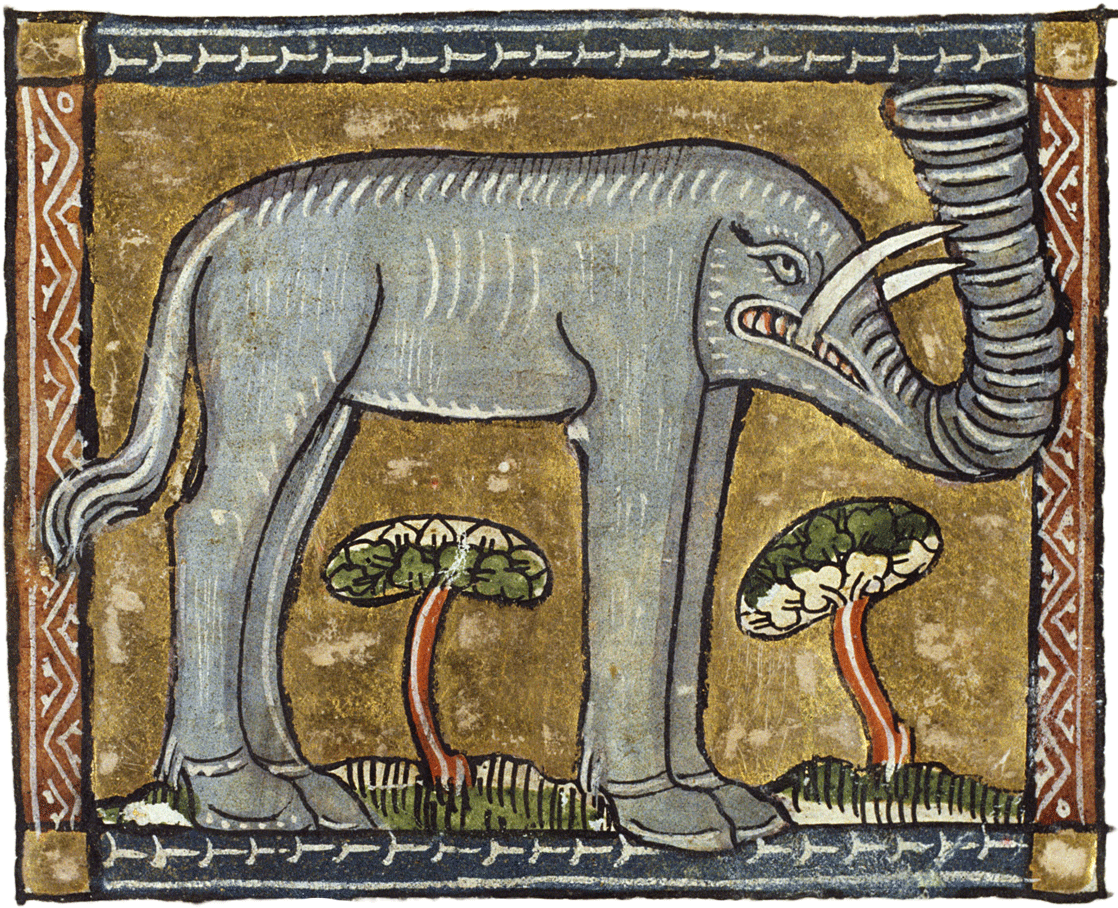

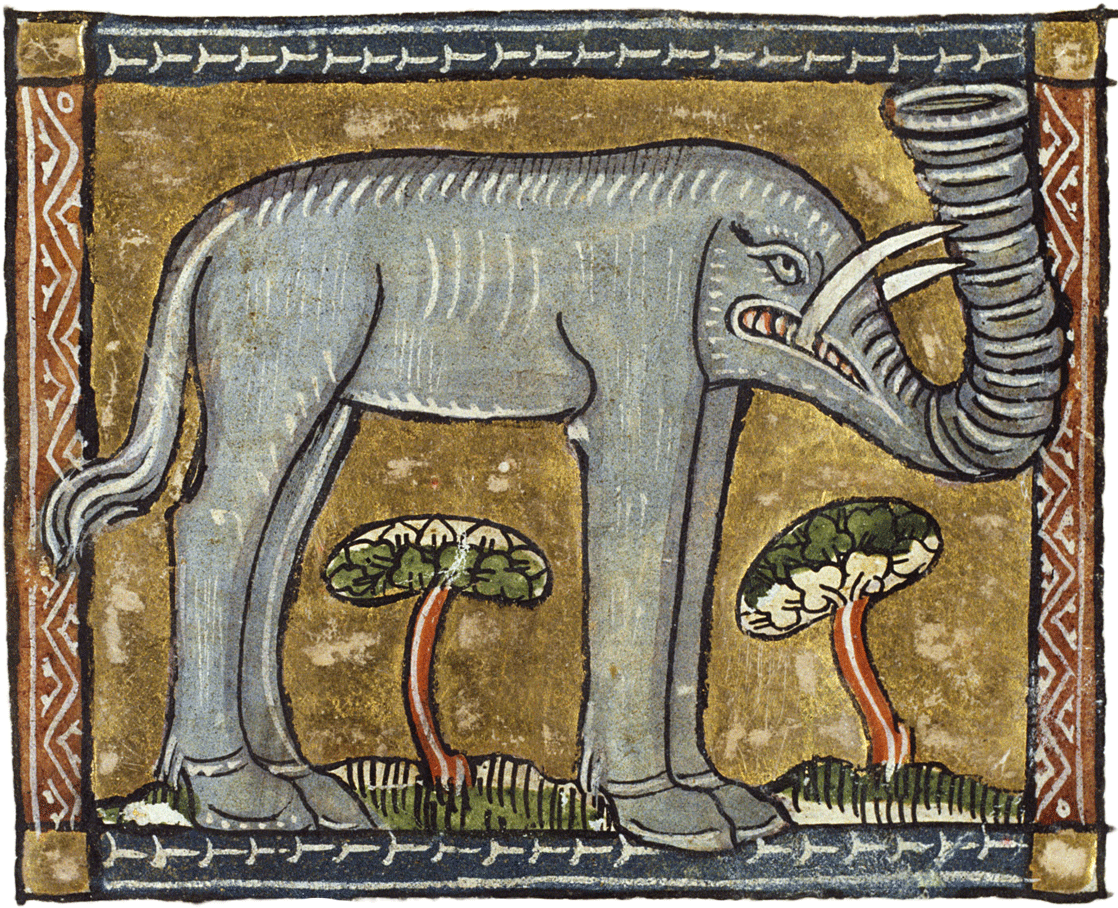

These types of scribbles are referred to as marginalia: That which takes place in the margins of a book. Marginalia can also refer to the illustrations and decorations in the margins of these medieval books. From these illustrations we can learn about the culture and the knowledge of the time in which the book was crafted. Often, they contained depictions of animals that show that the artist had clearly never seen the animal in person, resulting in creatures with absurd proportions (fig. 19). Another recurring subject matter are knights engaged in battle with snails. Though there isn't a definitive explanation for it, historian Lilian Randall proposes that the snails (fig. 20) are a metaphor for the Lombards (a Germanic people who ran the Lombard Kingdom) 12.

If we take a "small" leap in time to 19th century, we see that books have become much more widely available through industrialisation and the means of mass production. Mass production is a process that prioritises quantity over quality, resulting in a degradation of quality in produced goods, including books. William Morris was a designer who was at the forefront of the Arts and Crafts movement, which protested the decline of design standards by creating beautifully decorative and detailed work. One such project was the Kelmscott Press13 –founded by Morris–, a publishing house that took great inspiration from medieval illuminated manuscripts, while using contemporary printing techniques. The books they published featured frames and initials akin to their predecessors, but instead of calligraphing by hand, they printed reusable woodblocks designs (fig. 21). Similar to the medieval marginalia, the treatment and production methods of books that were produced under –what became known as– the Fine Press movement, reflect the circumstances of their creation.

Frames in illuminated parchment and the Kelmscott Press

We see another interesting usage of frames in medieval books, which follow a rich tradition of ornamental borders and illustrated margins. Because these books were made long before the invention of the printing press, each specimen was crafted through countless hours of meticulous and precise hand labour. This job, tasked to monks in a monastery, was very difficult and often took place under less-than-ideal circumstances. We know this because some scribes wrote little complaints in the books. An example of such complaints is "Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides,"11.

These types of scribbles are referred to as marginalia: That which takes place in the margins of a book. Marginalia can also refer to the illustrations and decorations in the margins of these medieval books. From these illustrations we can learn about the culture and the knowledge of the time in which the book was crafted. Often, they contained depictions of animals that show that the artist had clearly never seen the animal in person, resulting in creatures with absurd proportions (fig. 19). Another recurring subject matter are knights engaged in battle with snails. Though there isn't a definitive explanation for it, historian Lilian Randall proposes that the snails (fig. 20) are a metaphor for the Lombards (a Germanic people who ran the Lombard Kingdom) 12.

If we take a "small" leap in time to 19th century, we see that books have become much more widely available through industrialisation and the means of mass production. Mass production is a process that prioritises quantity over quality, resulting in a degradation of quality in produced goods, including books. William Morris was a designer who was at the forefront of the Arts and Crafts movement, which protested the decline of design standards by creating beautifully decorative and detailed work. One such project was the Kelmscott Press13 –founded by Morris–, a publishing house that took great inspiration from medieval illuminated manuscripts, while using contemporary printing techniques. The books they published featured frames and initials akin to their predecessors, but instead of calligraphing by hand, they printed reusable woodblocks designs (fig. 21). Similar to the medieval marginalia, the treatment and production methods of books that were produced under –what became known as– the Fine Press movement, reflect the circumstances of their creation.

Frames in illuminated parchment and the Kelmscott Press

We see another interesting usage of frames in medieval books, which follow a rich tradition of ornamental borders and illustrated margins. Because these books were made long before the invention of the printing press, each specimen was crafted through countless hours of meticulous and precise hand labour. This job, tasked to monks in a monastery, was very difficult and often took place under less-than-ideal circumstances. We know this because some scribes wrote little complaints in the books. An example of such complaints is "Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides,"11.

These types of scribbles are referred to as marginalia: That which takes place in the margins of a book. Marginalia can also refer to the illustrations and decorations in the margins of these medieval books. From these illustrations we can learn about the culture and the knowledge of the time in which the book was crafted. Often, they contained depictions of animals that show that the artist had clearly never seen the animal in person, resulting in creatures with absurd proportions (fig. 19). Another recurring subject matter are knights engaged in battle with snails. Though there isn't a definitive explanation for it, historian Lilian Randall proposes that the snails (fig. 20) are a metaphor for the Lombards (a Germanic people who ran the Lombard Kingdom) 12.

If we take a "small" leap in time to 19th century, we see that books have become much more widely available through industrialisation and the means of mass production. Mass production is a process that prioritises quantity over quality, resulting in a degradation of quality in produced goods, including books. William Morris was a designer who was at the forefront of the Arts and Crafts movement, which protested the decline of design standards by creating beautifully decorative and detailed work. One such project was the Kelmscott Press13 –founded by Morris–, a publishing house that took great inspiration from medieval illuminated manuscripts, while using contemporary printing techniques. The books they published featured frames and initials akin to their predecessors, but instead of calligraphing by hand, they printed reusable woodblocks designs (fig. 21). Similar to the medieval marginalia, the treatment and production methods of books that were produced under –what became known as– the Fine Press movement, reflect the circumstances of their creation.

Unknown, “Marginalized,” Lapham’s Quarterly, n.d.↩︎

Lilian M. C. Randall, “The Snail in Gothic Marginal Warfare” 37, no. 3 (1962): 358–67.↩︎

“Graphic Design and Visual Culture in Europe 1890-1945,” n.d.

Frames in illuminated parchment and the Kelmscott Press

We see another interesting usage of frames in medieval books, which follow a rich tradition of ornamental borders and illustrated margins. Because these books were made long before the invention of the printing press, each specimen was crafted through countless hours of meticulous and precise hand labour. This job, tasked to monks in a monastery, was very difficult and often took place under less-than-ideal circumstances. We know this because some scribes wrote little complaints in the books. An example of such complaints is "Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides,"11.

These types of scribbles are referred to as marginalia: That which takes place in the margins of a book. Marginalia can also refer to the illustrations and decorations in the margins of these medieval books. From these illustrations we can learn about the culture and the knowledge of the time in which the book was crafted. Often, they contained depictions of animals that show that the artist had clearly never seen the animal in person, resulting in creatures with absurd proportions (fig. 19). Another recurring subject matter are knights engaged in battle with snails. Though there isn't a definitive explanation for it, historian Lilian Randall proposes that the snails (fig. 20) are a metaphor for the Lombards (a Germanic people who ran the Lombard Kingdom) 12.

If we take a "small" leap in time to 19th century, we see that books have become much more widely available through industrialisation and the means of mass production. Mass production is a process that prioritises quantity over quality, resulting in a degradation of quality in produced goods, including books. William Morris was a designer who was at the forefront of the Arts and Crafts movement, which protested the decline of design standards by creating beautifully decorative and detailed work. One such project was the Kelmscott Press13 –founded by Morris–, a publishing house that took great inspiration from medieval illuminated manuscripts, while using contemporary printing techniques. The books they published featured frames and initials akin to their predecessors, but instead of calligraphing by hand, they printed reusable woodblocks designs (fig. 21). Similar to the medieval marginalia, the treatment and production methods of books that were produced under –what became known as– the Fine Press movement, reflect the circumstances of their creation.

Unknown, “Marginalized,” Lapham’s Quarterly, n.d.↩︎

Lilian M. C. Randall, “The Snail in Gothic Marginal Warfare” 37, no. 3 (1962): 358–67.↩︎

“Graphic Design and Visual Culture in Europe 1890-1945,” n.d.