CHAPTER I

“All art is quite useless.”

- Oscar Wilde

1.1 Overview on aesthetics of twentyish century

From the beginning of Western civilization aesthetic theory has been developed, enriched and motivated by thinkers, philosophers, and artists. They saw the experience of beauty as an appeal to the sublime. Plato, writing in Athens in the fourth century BC, argued that beauty is the sign of another and higher order. “Beholding beauty with the eye of the mind”, he wrote, “you will be able to nourish true virtue and become the friend of God .” At any time before the twentieth century if you asked educated people to describe the aim of poetry, art or music, they would have replied “beauty.” Beauty remained a value, as important as truth and goodness. Then in the 20th century aesthetics increasingly stopped being important and art has become in many cases a pure, self-oriented originality achieved by whatever moral costs it takes. Anything has the right to be called ‘art’ today, whereas art has an obvious impact on an individual. Art does not express the divine any longer, but simply follows the massive commune often for the sake of self advertisement and enrichment. We experience the big pressure of an image imposed by media and pop culture that makes us rethink and change in certain ways not just our physical surroundings, but our acts, values, music, manners, even languages, all of it becoming progressively poorer and more callous.

1.2 The roots of conceptual art

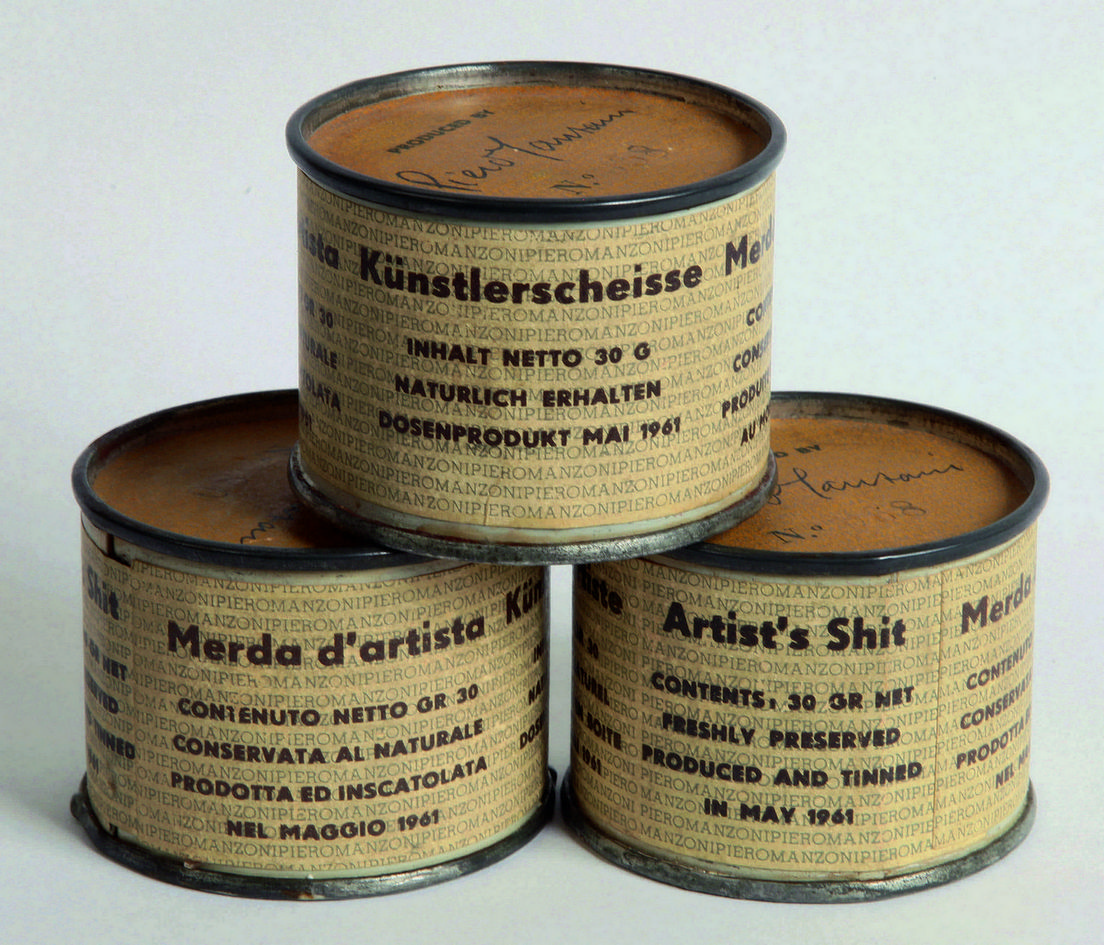

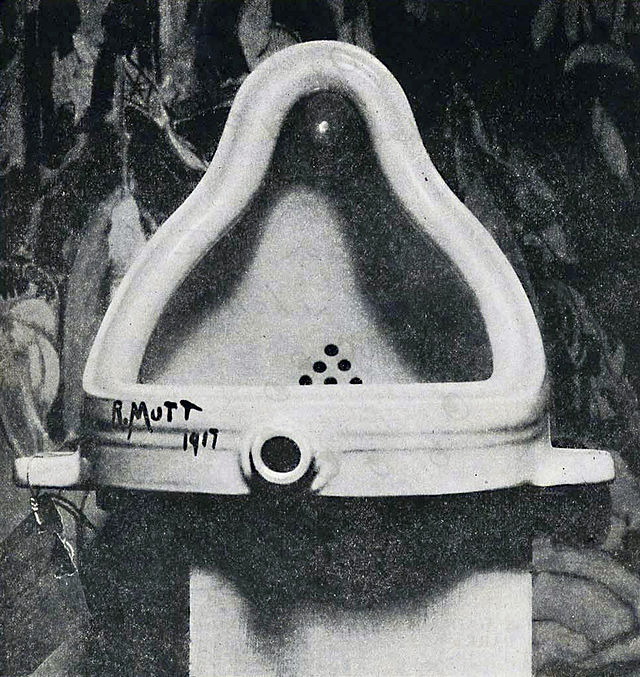

The great artists of the past were aware of the human life to be full of chaos and suffering. But they believed that the remedy for the bitter reality could be found in art. The genuine work of art brings consolation in sorrow and assertion in joy. It shows human life to be worthwhile. Many modern artists have become weary of this sacred task. The randomness of modern life, they think, cannot be redeemed by art. Instead it should be displayed. Of course an ancestor of today’s, observing conceptual art, could be rightly referred to the French artist Marcel Duchamp who signed an urinal with a signature “R. Mutt” and submitted it for an exhibition. This act was satirical, designed to mock the world of art and the snobs that go with it. But it has been interpreted in another way - the confirmation that anything can be art like a can of excrement (Piero Manzoni: Artist’s Shit, 1961) or Images by Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987) and Robert Mapplethorpe’s Jim and Tom, Sausalito (1977) (which showed one man urinating into another man’s mouth) even a pile of bricks by Carl Andre is proudly referred to as an art piece.

In such cases, art does not have any sacred status and does not raise us higher. It does not conveys moral or spiritual values, instead It becomes a human gesture among others; as meaningful as a laugh or a shout. “Art used to be a cult of beauty in the past, nowadays it often seems to encourage cult of ugliness instead.” Notice how people who look for beauty in art seem to be just out of touch with modern realities. Nevertheless, the art world understandably is a highly competitive place, and artists need any edge they can get, including a shock value to be recognized. But what is shocking first time round is boring and vacuous when repeated.

On the other hand, getting back to Duchamp’s Urinal, it has never intended to be beautiful. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t stimulate our imagination. Stimulating imagination could be called a key to what art seeks to do nowadays. Duchamp felt that art had become too interested in technique. His reason for making an artwork was a denial of all the things that people saw in art previously in order to explore the central question of art that in his opinion was lying somewhere else than beauty, rarity and skill. Duchamp himself had no idea how influential the discovery he had stumbled upon would become – a statement that a work of art is a work of art because we think of it as such. ‘He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - created a new thought for that object.' ('The Richard Mutt Case', The Blind Man, New York, no.2, May 1917, p.5.)

1.3 Ugliness

A defender of conceptual art may argue that an idea of certain artwork can be beautiful and there is nothing wrong in perceiving conceptual art from this perspective. It allows people to see the world in which they are living these days, an abstract world that isn’t ideal, but the world as it is some better place but of the here and now that teaches how to be and leave more at ease with it.

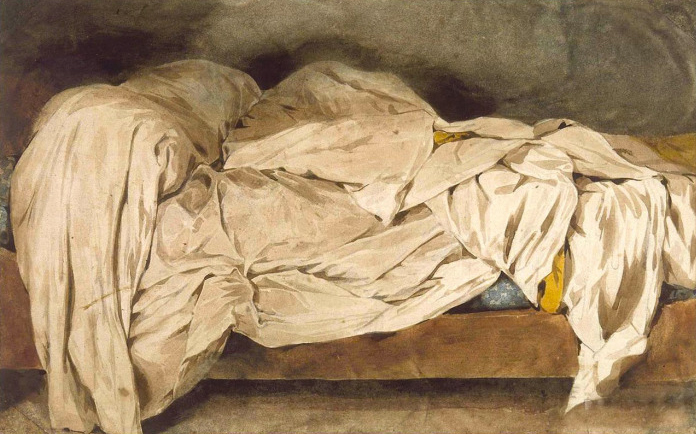

But take look at the example of Eugene Delacroix’s (Un lit defait, 1827.) It displays the artist’s bed in all its disorder. He depicts the world as it is with all its vanity and personal emotional chaos. But the bed is transformed by the creative act to become the symbol of the human condition that creates a bridge between the artist and us. It becomes suddenly much more than the depiction of every day life. Delacroix says, “See how these sweat-stained sheets record the troubled dreams, the tormented energy of the person who has left them and how the light picks them out as if they are still animated by the sleeper.”

Conceptual art is often an idea , a beautiful concept. But having an idea does not mean it is a work of art. A statesman or a scientist could come up with a beautiful idea but it does not make them an artists.

Some people describe Tracey Emin’s bed in that way. But the key of the separation between the works of art as in Delacroix and Tracey Emin’s example is that one makes ugliness beautiful and the other shares the ugliness that it displays. To me, the biggest and perhaps the most essential difference lies in this statement.

Breakfast with Frost, BBC 1999

David Frost: “What is it that makes that art rather than just a rumpled bed?”

Tracey Emin: “The first thing that makes it art is that I say that it is.”

Interviewer: “You say that is..

Emin: “I say that it is.”

Frost: “The second thing is that the Tate says that it is….But what do you want the viewer, the visitor to the gallery to say? Do you want…. You don’t want them to say, ‘I think that’s beautiful.’”

Emin: “No, no one’s actually said that, only me.”

Frost: “You think it’s beautiful?”

Emin: “No, no one’s actually said that, only me.”

Emin: “Yeah…. I do, otherwise I wouldn’t have showed it.”

Undoubtedly Emin’s work makes no attempt to transform the raw material of an idea but shares one sordid reality among others. Literal translation of modern life that does not pursuit to convey any moral or social values.

Undoubtedly Emin’s work makes no attempt to transform the raw material of an idea but shares one sordid reality among others. Literal translation of modern life that does not pursuit to convey any moral or social values.

“The art of today shows us the world as it is – the here and now and all its imperfections. But is the result really art. Surely something is not a work of art simply because it offers a slice of reality.”

Tracey Emin’s bed is a perfect example of “Literal translation of modern life that does not pursuit to convey any moral or social values". If you walked on a street and you saw a bed like that just standing there you would probably walk on. But surely if you saw the torso of the Apollo Belvedere lying in a skip you would be arrested by it.

1.4 Usefulness

In today’s democratic culture people often think it is politically incorrect to judge another person’s taste. Some are even insulted by the suggestion that there is a difference between good and bad taste or that it matters what you look at or read or listen to. But this doesn’t help anybody in the end, the reality is that there are standards of beauty which have a firm base in human nature and by understanding these standards the genuine work of art can be created.

“All art is absolutely useless,” said Oscar Wilde. This remark was intended as accolade for art that has a value higher than usefulness. People need useless things just as much as and even more than they need things for their use. Clear example of it is worship or friendship. These things are absolutely useless. And the same applies for art and beauty.

Our consumer society puts usefulness first and beauty is no better than a side effect. Since art is useless it doesn’t matter what we read, what we look at, what we listen to. We are captured by messages on every side, titillated, and seduced by appetite. And that is one reason why beauty is disappearing from our world. In our culture today the advert is more important than the work of art and art works often try to capture our attention as adverts do.

“The cynical assessment is that often contemporary art does not forge meaningful associations, but promotes entertainment and profit.”

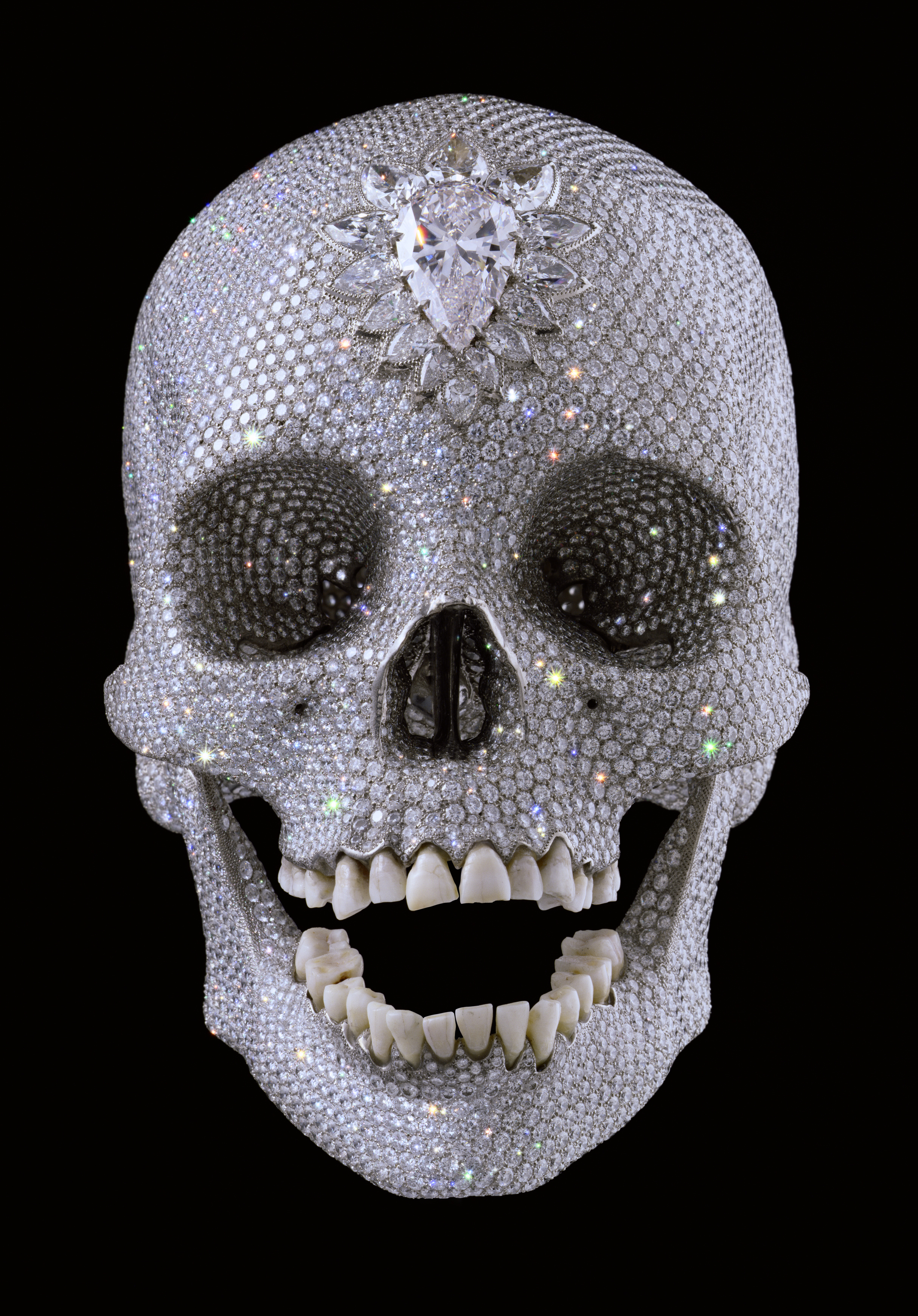

An example that comes to mind first is a Damien Hirst’s acknowledged bejeweled platinum skull (“For the Love of God” [2007]) “sparkling” with its “controversy” or macabre high-tech exhibits of dead sharks, sliced cows, or lambs in vitrines of formaldehyde. It is easy to imagine how Hirst’s tableaux of rotting meat (complete with maggots) “helped” the food business—but fame works in inscrutable ways.. Like adverts today’s works of art often aim to create a brand even when it has no product to sell, it sells itself.

1.5 Personal position

My assessment of art may seem very conservative and even hypocritical especially since I myself work in the field of progressive contemporary graphic design, but it must be stressed that to my personal view there is clear separation between art and design. Artists and designers both create visual compositions using a shared knowledge base, but their reasons for doing so are entirely different.

It serves people in two different ways and sometimes what comforts the design is not sufficient for the art (and other way around). One of the reasons I have chosen my path in art to be graphic design is its frankness, it does ultimately appears to be tied together with trade and commerce and yet it does makes the world aesthetically attractive and fills it up with beautiful physical surroundings. Both art and design needs creativity.

“creativity is about sharing. It is a call to others to see the world as the artist sees it… That’s why beauty can be found often in the naive art of children… Something of the child’s pure delight in creation survives in every true work of art… But creativity is not enough and the skill of the true artist is to show the real in the light of the ideal and so transfigure it.”

At the turn of the 20th century architects, like artists, began to be impatient with beauty and to put utility in its place. The American architect Louis Sullivan expressed the credo of the modernists when he said that “form follows function.” In other words, stop thinking about the way a building looks and think instead about what it does. I would like to use my personal experience to describe how Sullivan’s doctrine could be interpreted to justify a crime against architecture. I grew up in Moscow close to suburbs abundant with modern concrete architecture. The main idea of such architecture was the utility, in order to settle increasingly growing population and relocate people from communal houses. In the period of 1960s to 1980s Moscow has undergone a mass building. To fulfill an assignment rapidly and save money at the same time, the cheapest materials were used let alone any decoration or aesthetic component. As the result we may see today people simply do not want to live in buildings and concrete surroundings like that and trying to escape from it or move away, the pure utility with no regard to human needs can not be justified by any doctrine.This returns me to Oscar Wilde’s remark that all art is absolutely useless.

“Put usefulness first and you lose it. Put beauty first and what you do will be useful forever… It turns out that nothing is more useful than the useless. Ornaments in architecture liberate us from the tyranny of the useful and satisfy our need for harmony. In a way they remind us that we have more than practical needs. We are not just governed by animal appetites, like eating and sleeping. We have spiritual and moral needs too and if those needs go unsatisfied, so do we.”

.jpg)

.jpg)