Beauty in Unexpected Forms

Japanese aesthetics and their presence in Japanese contemporary design and society

by Irene Salo

Introduction

Learning from different

cultures and their traditions brings an

endless amount of inspiration and provides new

perspectives to look at the world. Marcel

Proust said: “There is a beauty in being

surrounded by the foreign – seeing things from

a new perspective, with new

eyes.1” Our

cultural values and background hugely

influence the way we perceive the world.

For a long time, I have

been fascinated by Japanese culture. In the

past, I was enrolled into an international

school, where I formed close friendships with

a Japanese family. I learned about their

traditions and visited them in Japan. Last

year, my interest was broadened further when I

went on an Erasmus exchange program in Aalto

University, Helsinki where I spent most of my

semester following Japan-related courses such

as Japanese watercolor woodcut, Ukiyo-e,

bookbinding and packaging design. My professor

in Aalto, Kari Laitinen, inspired my thesis

topic by mentioning a concept from Japan that

views the world in a seemingly opposite way

compared to the West.

These concepts find beauty in the most unusual places

such as in emptiness, subtlety and imperfection.

Reading more about these aesthetic

concepts turned my worldview upside down. In

Japan, simplicity is equivalent to emptiness

and it is seen as a positive quality whereas

in West, emptiness and nothingness are viewed

in a rather negative manner. As an example,

“Shakespeare: “Nothing will come of nothing.” Bertolt Brecht: “what happens to the holes when the cheese is gone?”2

Our graphic design

education predominantly concentrates on

Western design. Subsequently, it can be

interesting to learn about the practices from

other parts of the world, investigate what

could be taken from foreign ideas and whether

they could be valuable to Western graphic

design and our society. These Japanese ideas

are fascinating, because even though they are

ancient concepts, they are still visible in

Japanese contemporary society and deeply built

into their mentality. Graphic designer, author

and curator Kenya Hara states:

"Today, we seem to be experiencing a rationalization of the senses. The art of refinement has been half-forgotten, and attentiveness to detail, absorption, and slow engagement are neglected.3”

This statement applies to today’s world, especially in the West, with its overwhelming and constantly accelerating consumer and material culture and fast-paced lifestyles. This is also seen in the field of graphic design, including the rise of extravagant and rather inharmonious trends. Therefore, I wonder if Western design could benefit from a new kind of aesthetics that are so subtle and do not ‘shout out’ the message?

Simplicity contains numerous benefits for our technological and material-saturated society and ways of living, yet we keep on neglecting it and strive for the most complicated and excessive. Could we enhance our visual communication by examining the traditional Japanese aesthetic principles? This thesis will investigate the qualities and values of traditional Japanese aesthetic concepts, concentrating on simplicity, and analyze its presence and significance in Japanese contemporary design. Where are these powerful and inspiring aesthetic values originating? How did the discovery of simple beauty come about? What makes Japanese aesthetics distinctive from rest of the world? Why is this topic valuable and fascinating for a non-Japanese?

This research will analyze these matters in the context of the work of contemporary designer Kenya Hara among other notable Japanese designers. By using “Void” from the architect Tapio Periäinen, I would also like to explore the importance of simplicity from an ecological point of view against our wasteful habits of consumption. Sometimes the best answers can be found in the most unexpected forms.

1: Traditional Japanese aesthetics in modern Japan

Origin of Japanese aesthetics

Japan has a worldwide reputation for its focus on beauty in many aspects of its culture, such as in their arts, poetry, calligraphy, the traditional tea ceremony, consumer goods and architecture. The refined, simplistic aesthetic taste, seen especially in the traditional Japanese architecture, has played a huge influence on designers and artists in the West, most notably Vincent van Gogh and architect Frank Lloyd Wright.4 It has also inspired the minimalist movement, where things are stripped to its essentials.5

In order to understand the uniqueness of the Japanese aesthetics, it is crucial to get to know their origin and the Japanese worldview. Their concepts of aesthetics, starting from the Heian era (15th century),6 are deeply rooted in the Zen Buddhist thoughts of ‘material poverty, spiritual richness’ and the elimination of everything unnecessary in the surroundings and in the mind. Currently, Japan has become a fascinating mix of aspects from both East and the West. It seems as if the country has managed to develop and preserve its recognizable and distinctive traditional aesthetic values, even after the vast influence from the consumer culture of the West.

According to author Nancy Walkup, the geographic isolation of Japan played an important role in the development of the distinctive aesthetics.7 Being isolated by the sea protected the country from foreign invasion and influence and allowed for the development of original aesthetic ideas. Americans traders broke the isolation in the 19th century and since then the West has had an immense influence on the modern Japanese culture. Walkup explains that the Japanese term for art, ‘katachi’, means ‘form and design’. Its implication is that art is synonymous with living, functional purpose and spiritual simplicity.8

Inspired by Zen philosophy, the Japanese translated the ideas of the ultimate simplicity into aesthetics and design elements. The rock garden in Ryoanji temple is an example that demonstrates refined simplicity. This garden consists of 15 stones arranged apart from each other, bound by a vast emptines. This way, the focus is on the essence of the elements, while stimulating meditation.

Rock garden in Ryoanji temple

The essential aesthetic ideal of the traditional Japanese culture and worldview is harmony with nature. Despite the changes brought about by the westernization of Japanese culture, these ideas are still visible in the everyday lives of the Japanese.9 The deep appreciation towards nature can be seen for instance in the way the Japanese society concentrates on finding balance between man and nature. In the Heian era, Japan found a new focus on nature by appreciating its unpredictability and imperfections.10 The Japanese had to accept the harsh nature the country faces in every season, like earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and monsoons.

The high contrast between technology and nature, as well as the contrast between Western consumer influence and the pure Japanese traditions are very visible in Japan’s current landscape. When browsing through the busy streets of one of their biggest cities, such as a high-tech, future oriented city like Tokyo, it is hard to find any traces from the traditional values. The streets filled with masses of people, material hysteria, screaming bold colors and flashing billboards and advertisements, makes it look like any big Western city.

On the contrary, when entering the temples within the city or the rural countryside, one is bound by calmness and tranquility. Even though the contrast between the urban and the rural is so distinctive, it is exactly that which seems to fit perfectly, complement each other and come together harmoniously. It is those various temples and gardens spread around cities that indicate the Japanese awareness and bond with nature.

In his book on wabi-sabi, author Leonard Koren says that the traditional Japanese aesthetics are an exact opposite of the Western ideal of ultimate beauty.11 According to him, in most of the Western world the conventional beauty is something monumental, durable and spectacular, whereas in Japan beauty is seen in subtlety, simplicity and things imperfect.12 In the Western world, we are taught to strive for perfection and the most extraordinary results. It could be argued that West is also rather materially oriented, whereas the East traditionally emphasizes the spiritual.

The numerous aesthetic concepts that even the Japanese have trouble explaining are even more challenging for a non-Japanese. Yet, these concepts are something that each Japanese person understands deep within. These concepts, including 'Ma' and 'Wabi-sabi', depict a different kind of beauty. The common ideology of these concepts is that beauty can be found in the most unexpected forms.13 Wabi-sabi characterizes rural and desolate beauty while Ma, an empty and formless beauty, sees emptiness as the ultimate simplicity.14

Beauty in the desolate

Wabi-sabi is the most visible and characteristic aspect of the traditional Japanese aesthetics. Wabi-sabi ideas are closely linked to Zen Buddhist thoughts and were present already in the earliest examples of Japanese literature.15 Wabi-sabi is not just an aesthetic concept, but it could serve as a way of life that ignores material hierarchy and concentrates on the essence of matters. The concept depicts refined simplicity and celebrates things that are crude, faded and unnoticed. Leonard Koren explains that Wabi-sabi sees beauty in the most unconventional, minor and overlooked matters.

“Wabi-sabi is the beauty of the imperfect, impermanent, incomplete, modest, humble and the unconventional. Wabi-sabi objects are earthy, simple, unpretentious and made out of natural materials.16” In short it is the opposite of today’s mass-produced, technology oriented culture and modernism.

“Wabi-sabi is not about gorgeous flowers, majestic trees, or bold landscapes. It is about the minor and the hidden, the tentative and the ephemeral: things so subtle and evanescent that they are invisible to the vulgar eyes.17” As an example of this; wabi-sabi would not see beauty in the blooming cherry blossom trees, but in the process of the leaves dying and withering away. Seeing beauty in the ugliness is uncommon in our world and clearly something that not everyone can appreciate. In order to learn to appreciate the beauty of it, one needs a different mindset, one that is not prejudice.

The Japanese tea ceremony is considered as one of the most important traditional Japanese arts. The ceremony symbolizes the ultimate, almost primitive, simplicity. “Although Wabi-sabi quickly permeates almost every aspect of sophisticated Japanese culture and taste, it reached its most comprehensive realization within the context of the tea ceremony”,18 The tea ceremony ‘celebrates’ the mundane, everyday ritual of drinking tea. What makes it less ‘mundane’ is the fact that it is taking place in a special tea hut; a completely empty space. There is nothing else in the room apart from some temporary decorative object like a flower arrangement.

The tea ceremony is the definition of aesthetic simplicity, harmony, respect and tranquility. Finnish architect Tapio Periäinen states: “its ideal, to come closer to nature, is realized by sheltering oneself under a thatched roof in a room which is hardly ten square feet.19” It serves as a pause and a quiet moment away from the hectic daily lives, and an as appreciation of that moment.

Learning to appreciate and understand Wabi-sabi ideas could free people’s minds from ignorance, and wake them out from their everyday ‘numbness’. It could serve as a reminder that we are on this planet only temporarily and that all our material belongings are impermanent. It could make us put emphasis on the things that truly matter and eliminate the unnecessary from our lives.Some aspects of Wabi-sabi seem similar to modernist thought. 32Although both of them embrace simplicity, this concept is the opposite of modernism. Wabi-sabi is human and nature-oriented, whereas modernism is technology-oriented. Modernism concentrates on endurance and man-made aspects; Wabi-sabi is about natural materials and impermanent things.20

The essay In praise of Shadows by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki is an inspiring insight into the world of Japanese aesthetics. The essay is about how oriental art and literature represents an appreciation of shadows and subtlety.

“Whenever I see the alcove of a tastefully built Japanese room, I marvel at our comprehension of the secrets of shadows, our sensitive use of shadow and light. The “mysterious orient” of which Westerners speak probably refers to the uncanny silence of these dark places… Where lies the key to this mystery? Ultimately it is the magic of shadows.21”

The essay compares the cultures of the East and the West and discusses traditional Japanese aesthetics in contrast to the changes westernization brings to Japan, and how the West is always striving for progress and searches for perfection. Some of the typical characteristics of Japanese aesthetics include asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, economy, modesty, and appreciation of the honest integrity of natural objects and processes.

Wabi-sabi ideals are most evident in the arts, architecture and interior design. For example, famous fashion designer Rei Kawakubo of Commes des Carcons is known for embracing wabi-sabi aesthetics in her designs. The asymmetrical, worn-out, and deconstructed elements of these garments show that beauty does not always need to exist only in the conventional.

Rei Kawakubo, Commes des Carcons.

Empty

Emptiness is the core concept in Japanese aesthetics. Periäinen explains the meaning of ‘Ma’ in his book ‘Void’ by “being the pure and essential void between all things22” and the ultimate form of simplicity. Nothingness is the center and a space where things originate and evolve from.23” Ma is in the Japanese architecture, garden design, music, flower arrangements, calligraphy and poetry, and like Wabi-sabi, Ma is a way of life, not only a philosophical and artistic concept.

Simplicity in the West has existed only for a little while compared to Japan, where it has been an important part of life for more than 300 years.24” In the West however, simplicity was first introduced by the American arts movement minimalism. It began in New York City in the late 1960s and notable contributors include Donald Judd and Frank Stella.25”

Emptiness, in the West, usually has negative connotations and is linked with words such as boring, un-sophisticated and unfinished. In the East, emptiness possesses endless possibilities and is the element of ultimate sophistication. To describe the meaning of Ma, Periäinen uses the Japanese flag as an example. The flag has a red circle in the middle, surrounded by blank space. The flag does not have any profound meaning to it, but the emptiness around the red circle is open to many interpretations, a rising sun being one of them. Periäinen also describes Ma by being the pauses in speech, which make the words standout and the white space around letters that enables the shape to exist:

“It is the purposeful pauses in speech, which make the words stand out, and it is the quiet time we need to make our busy lives meaningful. It is the silence between the notes, which make the music, and MA is what creates the peace of mind we all need, so that there is room for our thoughts to exists properly.26”

The famous painting Pine Trees (1539-1610) from Hasegawa Tohaku is a great example of beauty seen in emptiness and the use of negative space. The painting consists of only a few pine trees wrapped around the mist. It is the emptiness of the mist that allows those trees to stand out and it is what creates the powerful atmosphere of the painting.

Pine Trees (1539-1610) by Hasegawa Tohaku

Emptiness plays the most important part in the living space and interior decoration of a Japanese house27”. A typical Japanese house contains peacefulness due to the predominant emptiness. The most sophisticated Japanese houses contain no unnecessary objects or decorations and is consequently free from clutter. The dominance of emptiness makes the objects present to stand out. To the eyes of a Westerner, Japanese houses may seem modest due to the sizes of the rooms and the lack of furniture. During my stay in Japan, I was surprised to see that Japanese rooms do not have what is necessary to Western houses: beds, shelves and a large dinner table with chairs. The rooms in a Japanese house are used in a multifunctional manner; for example the beds are stored away during the daytime, in order to use the space for something else. The emptiness in the houses allows the rooms to stay flexible and adapt to different requirements.

This kind of lifestyle is quite contrasting to the Western standards. It seems as we need stuff in our surroundings to fill the void and to create meaning in our lives. This can be seen especially in most Western interior design, where we have the need to cover our walls with paintings and frames and tables filled with all sorts of decorational objects. One exception of this is Scandinavian design, where simplicity, nature and the ‘less is more’ concept are the key design elements. Kenya Hara explains, that the past, we needed this kind of extravagancy to demonstrate the power of the king or an emperor, but in today’s world kings do not possess such power anymore and such ‘show off’ is not necessary.28”

Another aspect of Japanese life where this kind of refined simplicity is found is in the Ikebana flower arrangement. Hara claims: “a vessel full of something, mounted high with whatever it may be, is never as beautiful as one that is empty.29” This can be applied to the art of Ikebana, where only a couple of flowers and branches are used in a vase. Natalie Avella, author of ‘Graphic Japan’, points out that:

“The Japanese sensibility sees no beauty in a mass of flowers in a vase. The single flower loses its effect in the mass, and opulence alone is not considered a virtue in an arrangement.30”

Limited, careful use of material and space and the balance between those two in Ikebana is rather similar to the method of work of many of Japan’s most well-known designers: restrained use of text, color and line.In this chapter, I have discussed two notable Japanese aesthetic concepts. The next chapter analyses how these philosophies are used in contemporary context, focusing most specifically in graphic design.

2: Traditional aesthetic values in contemporary Japanese design

Emptiness in communication

The contemporary Japanese graphic also displays a unique mix of traditional cultural influences while pushing towards global innovation. The design values concentrate on quality, elegance and innovative thinking. The design style is focused on simple and clean design solutions, and leans towards use of natural materials. In the Western world, it is often acknowledged that modernity will wipe out cultural traditions. Conversely, Hara views design as a cultural product and that “design should aid you in tracing perceptions and objects to their origins.”30 That being said, Japanese design often uses traditional ideology successfully transforming and updating them into contemporary context.”31 Simplicity is the key design element and it is the prevailing aspect of Japanese design. It is important to note here that the term ‘simplicity’ does not imply a lack of content.

Kenya Hara explains Japan’s fascination towards simplicity and minimalism by being “the most comfortable way for Japan to face the world.32” Hara is seen as the future of Japanese design, because of his ability to express and communicate a clear Japanese design philosophy that is aware of the past and insightful to the present.”33 He applies everyday observations with reflections on Japanese aesthetics and sensitivity to his work. Hara believes that Asian countries hold a key cultural resource that cannot be found anywhere else in the world and that “lifestyle has value in Asia”. Hara said: “The Swiss have their cheese, the French their wine, but Hara’s future Japan will be based on the export of a way of life.”34

Hara’s design principles are profoundly associated with the Japanese aesthetic concept of emptiness. Emptiness is similar to the Western idea of simplicity. There are, however, numerous differences with one being the fact that in Japan it is viewed as a positive quality. Emptiness is the “possibility yet to be filled.”35 Hara’s book ‘White’ is entirely dedicated on this subject matter, white being closely intertwined with emptiness. Hara explains that emptiness is what makes people and things what they are: “reality can be understood as background noise with nothing much going on and out of emptiness would (ideally) emerge the viewer’s questions, theories, and efforts to forge independent meaning.”36 Hara believes this to be a uniquely Japanese quality. “I hope to design outside the consideration of a form”37, he explains. Hara uses a vessel to explain the value of emptiness in graphic design:

“The mechanism of communication is activated when we look at an empty vessel, not as a negative state, but in terms of its capability to be filled with something.”38

If a vessel is already filled with stuff, it cannot be filled anymore and subsequently fails to present any new opportunities. Emptiness lets the mind and its creativity wander freely. For instance, Japanese conversations use emptiness the same way Hara uses empty space in his design work. He writes about the power of non-verbal communication such as a nod or eye contact that can convey so much.

The Japanese way of communication is full of emptiness: subjects of sentences are often left unsaid and left for the imagination and speculation.39” The Japanese people see words as not always necessary in a conversation. This opposes the Western standards of communication, which is more direct. In most countries, especially in the United States, a silence in a conversation is considered awkward and the conversation needs constantly go on to avoid awkwardness. Hara views people reaching a harmony in silence to be a highly sophisticated level of communication. Listening is a crucial part of it and this applies also to design: “good communication has the distinction of being able to listen to each other, rather than to press one’s opinion onto the opponent40.” Hara explains: “Each party must work to surmise the other’s position. This mutual work eliminates three or four steps in the dialogue before the first word is even spoken.41”

Hara’s work has elements of courtesy that can be linked with the Japanese mentality of politeness and respectfulness. As he states, a good design should not always impose ideas and opinions onto its viewer; instead it should leave room for interpretation and the viewer to experience the work, also from a personal, imaginative level.42 Hara, in common with many Japanese artists and designers, uses a lack of detail and void around an object in order to leave the interpretation up to the audience. His design of the perfume bottles for the Japanese fashion brand Kenzo obeys his design aesthetics and taste; it is all about the clean, simple form. Nothing unnecessary; it revolves around the functionality of the object in its purest form. It is a good example how emptiness could be a powerful design element.

Designing for the senses

Japanese design emphasizes how an object is felt or accepted. “Hara intensifies the need to critically adjust our understanding of the senses. He challenges the simplifications that inform much present day thought concerning what could be felt, experienced, and emotionally negotiated."43

Hara states that in today’s world a lot of slow engagement is neglected and replaced by a digital screen and that our senses must be ‘awakened’ from the mind-numbing routines of our daily lives. Hara’s ‘HAPTIC_Awakening the senses’(2004) exhibition does exactly that. It focuses on the interaction between an object and human senses, stimulating and using them to change our perception of our surrounding. The exhibition consisted of contemporary designs researching the theme of perceiving senses through material choices, shape, color and texture. His motive was to design an object through which a person can sense and physically feel something.

The logo of the exhibition was letters drawn with cultivated fungus. An example from the exhibition that demonstrates this kind of awakening is the limp remote control. When the remote control is switched off, it hangs down as if it were dead, similar to Salvador Dali’s surreal painting style of the melting clock. The material used for the production was unusual and was responsive to the touch of a human. New perspective on the so-called mundane objects is beneficial, because it enables us to see things in a new light.

Defamiliarization of the ordinary

Hara states that ‘defamiliarization’ is closely related to ‘white’ and emptiness. “White moves in the opposite direction of chaos; it is the singular image that emerges from disorder.”44 He explains that when he meditates on an object, it becomes refreshingly different, as if he had just encountered it for the first time.45 When thinking about our everyday objects, we see and use them every day but yet we do not really acknowledge them and the possibilities they possess. These objects may have become too common for us, so that they have become something trivial. Hara believes that a good design creates another perspective on something and the user will “never look at an everyday object in quite the same way again”. He calls this kind of thought process an ‘awakening’; something that could deepen our understanding of objects and our surroundings. It could awaken us from the numbness of being in our daily comfort zones and help us to regain perspectives of our surroundings and the objects around us. He states: “design should make the known become unknown.”46

Hara’s designs defamiliarize every day objects by distortion and manipulating the scale or the perspective. His exhibition ‘Architect’s Macaroni Exhibition’ is a great example of that. Hara asked twenty architects to redesign macaroni that is 50 times bigger than a normal macaroni. The main research question was ‘what does macaroni and architecture have in common?’ The architects had a total freedom of redesigning pasta, which resulted in complex and futuristic designs that are unrecognizable as the pasta found in the supermarket.

Akio Okumura: i flute. Kenya Hara: Architect's Macaroni Exhibition

It is not as creative to design things representing their original form; they grab more attention when they are out of the ordinary and present new possibilities and dimensions. Surely, these designs of the pasta are too crazy and complex to be sold commercially. It does, however, make the viewer look at the ‘boring’ pasta on our plates in a new light and realize its beautiful forms that we hardly ever pay attention to. Hara explains how the ‘defamiliarization’ of an everyday object works. He talks about how numerous artists, including Yasuhiro Ishimoto47, have tried to transform ordinary flowers into something unfamiliar.

”Yet if we perceive a flower as a living entity, even in a picture, we can come closer to reading its true essence. Photographers often compete to take pictures of flowers for reasons that have nothing to do with their beauty. Rather, they desire to reach the point where they can capture the living flowers in a way that no one ever has before.48”

An object that we encounter constantly on everyday basis is likely to become so normal to us that it becomes almost invisible. Design and art can make us rediscover these objects, making them exciting again, and ultimately making daily lives more exciting. When we see an object we take for granted in an unfamiliar context or form, we suddenly start seeing it again. The ordinary objects around us may not have much aesthetic appeal at first glance, but they do play an important part on our lives and indicate things about our existence.

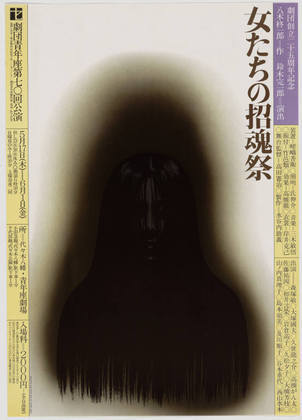

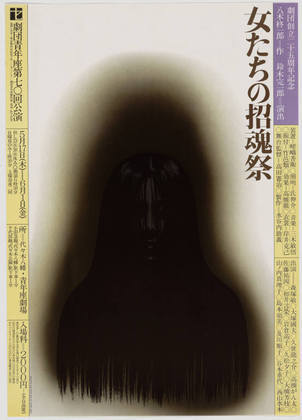

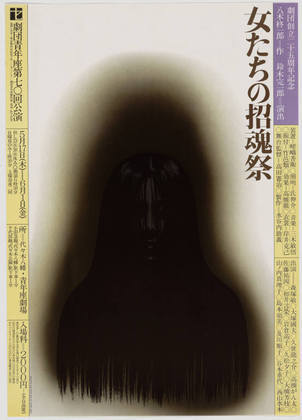

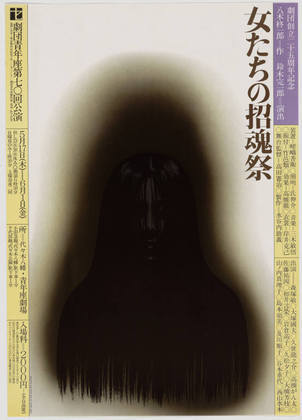

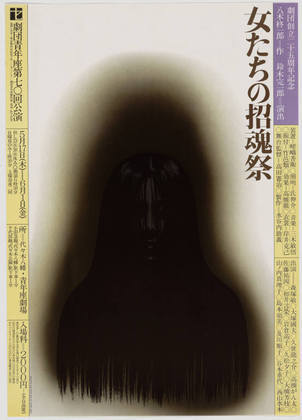

‘Gurafiku49 is an online magazine dedicated to showcase contemporary Japanese graphic design. Exploring the online magazine, the links to the traditional concepts are evident in many of the poster designs. For instance, the images and typography are often wrapped around empty space. Wabi-sabi elements can be seen in the hand-made aspects and playful imperfections. The influence from Western graphic design is obviously evident, but the usage of empty space, simple shapes and hand-made imperfections and textures indicate the underlying inspiration from the traditional ideals. Writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery states:

“Perfection (in design) is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but rather when there is nothing more to take away”.50

This statement applies to a lot of these poster designs where the design elements have been stripped to the maximum; yet still remain interesting for the viewer. It is intriguing how these designs possess the opposing atmosphere to the vivid and hectic landscape of the city. Instead of being imposing and shouting the message, these posters gently allure attention. Such ‘in your face’ approach is not always necessary, when the design is able to communicate a clear visual idea. The refreshing emptiness around the typography and the images together with the pastel color palette and bold unpretentious lines catch the attention immediately and is pleasing to the eye due to the peacefulness it emits through the harmonious and well-composed design elements.

Graphic designer Koichi Sato’s posters are a good example of a mix of traditional taste together with contemporary and futuristic imagery. Graphic designer Shigeo Fukuda’s51 posters often are inspired by the possibilities that negative and empty space possess. He uses those qualities to create optical illusions. His posters portray a creative way of using negative space for his benefit. When white space is used in an intriguing manner, it transforms into foreground. “The emptiness becomes the positive shape and the positive and negative areas become intricately linked.” It is often a lack of controlled white space that produces visual noise and inharmonious design. Author Alex White supports this claim:

“Emptiness in two-dimensional design is called white space and lies behind the type and imagery. But it is more than just the background of a design, for if a design’s background alone were properly constructed, the overall design would immediately double in clarity and usefulness.53”

Dynamic white space, abstraction and removing unnecessary details are the key to sophisticated design. He states that most design education is concerned with combining and sometimes inventing bits of content and it almost always overlooks the critically important part of the design that goes unnoticed: the background spaces and shapes. White space is like the glue that holds all the other elements in place.54

Poster design by Koichi Sato

Redesign of chocolate bar

3: The value of emptiness in Japanese design and society

Sustainability and design

As seen in the interior design of Japanese houses and in Zen Buddhist ideas, Hara sees the importance of removing all the decorations and everything that is unnecessary. Clutter hides and distracts us from what is truly meaningful. This design philosophy can be especially seen in the products of Muji55. Muji’s aesthetics and ideology is directly derived from the Japanese aesthetics of emptiness. It is distinguished by its minimalism and respect towards nature. It emphases on recycling and avoids waste in production and packaging. It also emphases a no-logo policy56, implying that only a little amount of money is used for marketing and advertisement. Their design style has been described to have ‘mundanity, being ‘no-frills’ and ‘minimalist’ and also as ‘Bauhaus-style’.57

Muji’s product design and brand identity is based around the natural materials and efficient manufacturing processes. The products have a very earthly color palette and all the product labels are the same and indicate only the contents of the product. The photograph below of a man surrounded by void basically summarizes the ideology of Muji. The man on the photograph looks so small and humble amongst the vast greatness of void, which fits in with their ideology that man is not the center of the world, but equal to everything and that nature cannot be controlled; instead, we should strive for harmony with it.

MUJI advertisement, 2003, "Horizon" poster, Uyuni Salt Lake

RE-DESIGN daily products of the 21st Century’ is another of Hara’s exhibitions. It shows how daily life serves as a great source for design.58 These ordinary objects include toilet paper, tea bags and matches. The goal was to redesign familiar objects in a unique way to create new experiences and ways to use them. Some of the objects were made to make our daily lives more beautiful and our daily routines more enjoyable. Some objects did the opposite; in fact some became harder to use in order to convey a serious message.59 This happened with the redesign of toilet paper, designed by Shigeru Ban60: the hole in the paper roll was cut in a square shape instead of a circle, which made it difficult to roll and in the end you consume less toilet paper. Making a little but substantial alteration to the design, changed its purpose: instead of being just a toilet paper roll, it now serves as a reminder of our wasteful and unsustainable habits and that we should cut down and slow consumption of paper.

Matches were redesigned in a way that they look like real twigs from a tree to remind us of diminishing forests. These redesigned products are all about preservation and renewal by making simple, yet thoughtful alterations. The chocolate bar may seem at first just like an ordinary cute pattern, but because of the cut of the pattern, you will end up eating less chocolate, resulting in fewer consumed calories. This reminds the audience to cut down sugar consumption, because of the numerous underlying health hazards.

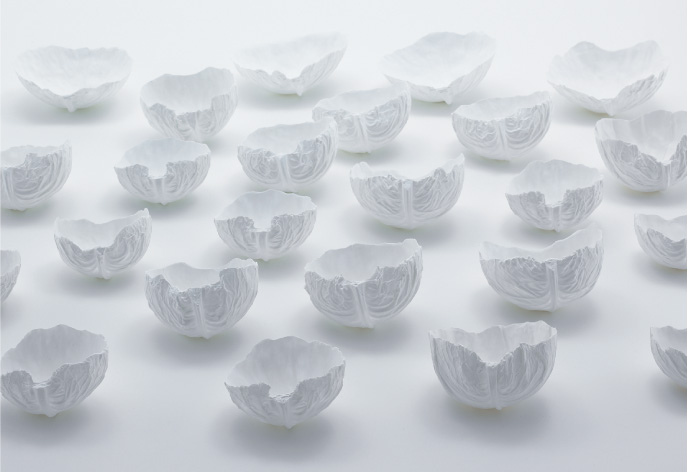

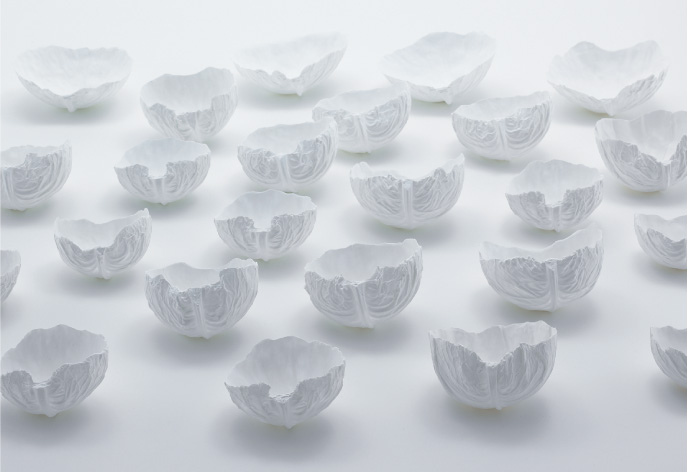

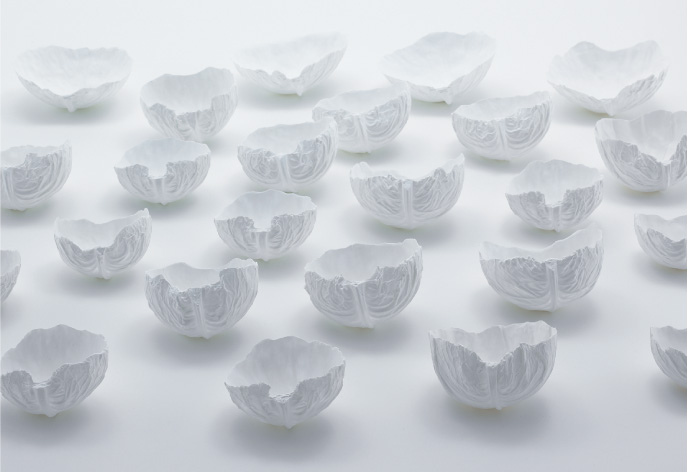

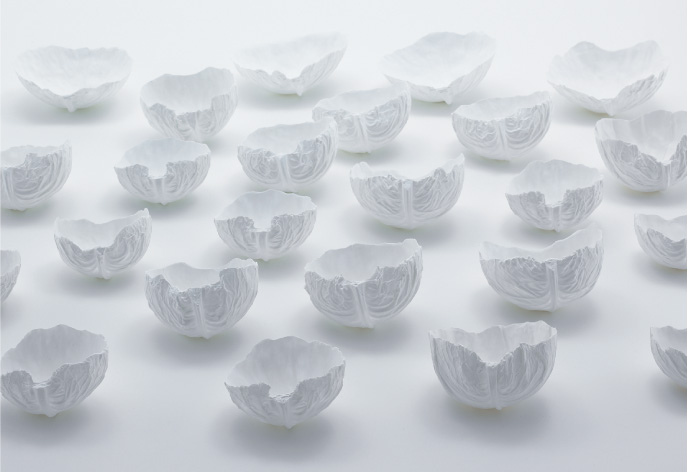

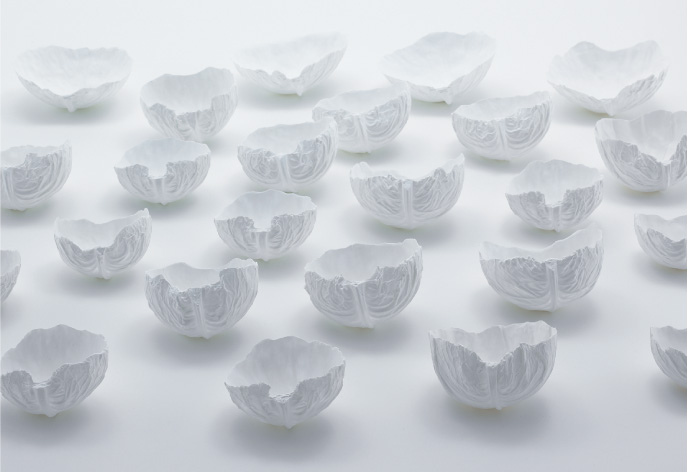

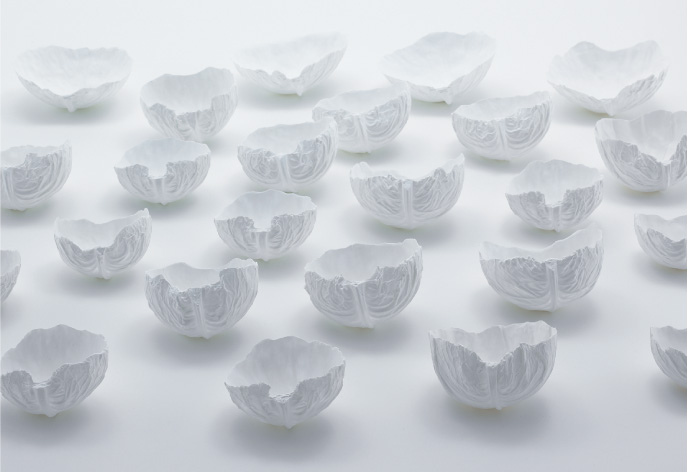

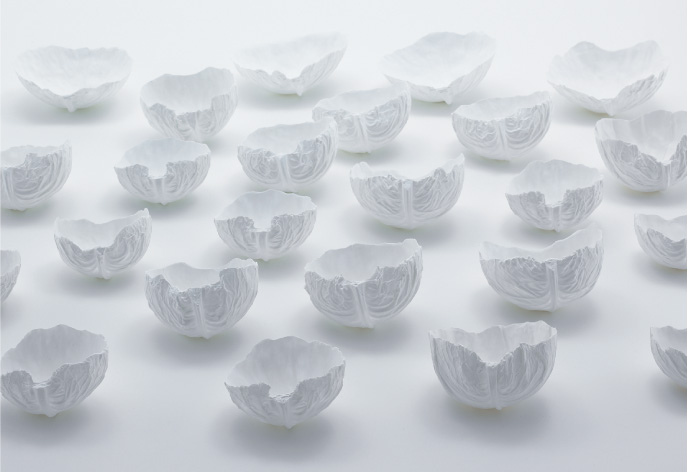

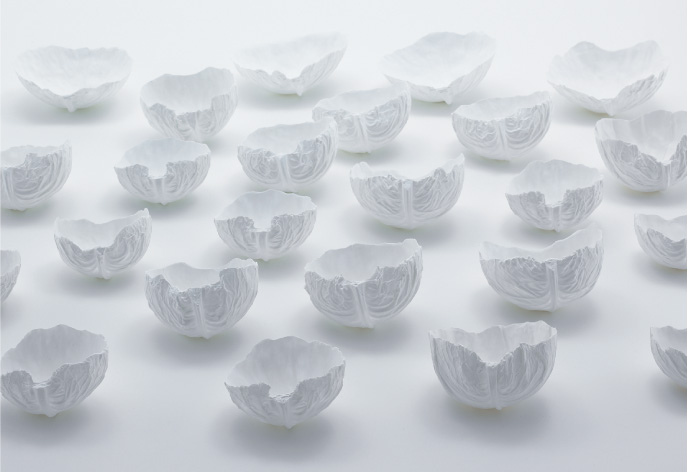

In his book ‘Designing Design’ Hara elaborates on the importance of emptiness in both the visual and philosophical traditions of Japan and its application to design. The title of the book means changing the traditional into totally new ideas, such as changing its original design, including shapes, functions and concepts.61This creates a new way to face our daily life and daily products. These works are about the products of daily life, like square tissue and redesigning pasta. The realistic looking silicone molded ‘cabbage bowls’ by designer Yasuhiro Suzuki peels off leaves that become its own functional bowl. Designers should face the real needs of our daily life that could help them to find the real meaning of contemporary product design. In order for us to make an aesthetic judgment of an ordinary object, we must first experience that object in a different form, giving it greater significance than the other, similar, objects around it.

Yasuhiro Suzuki: Cabbage Bowls

Naoto Fukusawa’s62 juice box package design portrays a new imaginative approach on packaging design. The design imitates the skin textures of real fruits. They bring out a new simplistic, refreshing take on packaging design that unquestionably stands out from the rest of the food market. The simplicity of the design puts the emphasis on the function and essence of the object. It also makes us face the reality that we tend to forget or simply ignore where for example our food comes from and therefore we could create more awareness with more design approaches like this. According to Hara, design should not aim for the short-term response, but focus on the long-term purpose: “if every designer had this kind of pursuit, the quality of modern designing could be improved. When the public understands designers, the design industry of modern products could have a bigger market.”

Naoto Fukusawa: Juice Skin

The word ‘Re-Design’ includes the meaning of recreating the definition of normal products. Hara encourages designers to improve the value and functions of these daily products in order to find the purpose of designing. Hara uses the redesigning of a cup as an example: “designers can follow the ideas of original function, which is holding water but not the current structure and trends. As long as designers could produce items that can be filled with water, these products could be called ‘cup’.63” Our visual environment that we interact with every day plays an important part on our lives morally and socially.

Hara’s designs combine active cultural imagination with a pragmatic engagement in everyday life. Design can be used to communicate a country’s values, history and possibilities. It can manipulate reality in a way so that it brings a new perspective to the viewer. Taking the ideas of simplicity from the East and adapting it to our way of life could enhance not only the quality of our lives but our surroundings as well. An example of a mix of Eastern philosophy with Western design is demonstrated through the Rings-stools designed by Nao Tamura for Artek. Nature has drawn the ‘yearly rings’ of each tree differently: the thick rings indicate good years and the thin, the bad.64 This is a unique approach of using natural elements in a contemporary context.

'Yearly rings' chair, Artek

Ecological value of emptiness

Emptiness does not only present positive qualities within the arts, design and architecture, but has a massive potential in improving our environment that is facing some of the most serious issues of human history ranging from climate change to over population. According to Periäinen, emptiness creates possibilities for an ecologically sustainable coexistence of man-made environment and nature. “Let us think about those additional 7 billion people + the continuous economical and material growth desired by those already living.66”

Periäinen also says:

“Void empties thoughts of routines and prejudices and outgrown value structures. In Eastern thought the emptying of the mind is a prerequisite to grasp universal truth or enlightenment. It could help the West, as well, to embark upon a new and more natural era.67

He wonders why so little emptiness has been interpreted in the Western lifestyles and mentality compared to Japan. In fact, West is known to be the culture of the full and excessive. Using empty space would not only be important for the restore and maintenance of the ecological balances, but also for the development of a more natural ways of living. This is because emptiness in practice eliminates material objects and borders. Meanings that emptiness offers a really powerful tool to decline materialism, thus easing the pressures put on living nature.68 The Zen Buddhist thoughts teach people to aim for ‘non-material emptiness’. Periäinen said:

“The non-material emptiness and the balance between the void and material could perhaps again be achieved by combining the old wisdom of the East with the technological know-how of the West.69”

This could be applied for example in the sizes of produced objects and careful choice of environment-friendly materials. Periäinen states that “In Japan, seeds have also been sown for Western industrial product development: the size or volume of several gadgets, their amount of materials and components, is constantly reduced.”70” Like in Japan, the Nordic countries have also adapted a simplified and reduced design language that has become part of their country’s identity. This design language has not only aesthetic value, but is used in a position of more prominent ecological importance.

Designers today are familiar with the current tide that adds value to the creation of something new. I believe that design should seek for innovative, forward-thinking and experimental solutions. However, we have to do it in a conscious way that is aware of the currents of our world and in a way that we do not end up erasing the traces of our past and everything else standing on the way. To my understanding the Japanese sensibility is probably more adjusted towards preservation rather than only aiming for something completely new. We could make a change by reducing the size of gadgets and minimalising waste in production and making conscious choices for materials. To conclude this chapter, simplicity is not just an aesthetic concept but possess endless possibilities and solutions to enhance our lives and the environment. We have now researched simplicity and emptiness from a traditional side, in contemporary design context and from ecological point of view.

Conclusion

The starting point of this thesis was a personal fascination and curiosity towards Japanese culture and design. Through this research I came to find the real underlying fascination and motive for my interest. I realised that I can relate to the Japanese values and strongly believe this is because my home country Finland shares a lot of similar values as Japan, such as appreciation of nature, quietness and simplicity. Just like in Japan, awkward silences are acceptable and one does not need to talk all the time just to fill the silence. Finnish design is also world famous for its ‘whiteness’, simplicity and use of natural materials and nature as the subject matter.

In fact, Japanese simplicity seems to be comparable to Western design principles of ‘less is more’; especially seen in Scandinavian and Nordic design. The major difference between them is that simplicity has existed far longer in Japan and is implemented into nearly every aspect of their society and culture. The lifestyle and aesthetic values in rest of the Western world are quite contrasting to the ones in Japan. Another major difference is that in the Western world emptiness is always viewed as something negative. Western world seems to have a phobia of emptiness where as Japan has a phobia of clutter. Emptiness in Japan means a new beginning; the origin of everything and full of possibilities.

The traditional Japanese views on beauty are also much different to the ones in Western society. Japanese values suggest a more subtle beauty that is imperfect, evanescent and rust. In design and visual communication, the focus seems to be on listening as a way of communication instead of ‘yelling out’ or imposing the message. In my opinion, in today’s consumer-saturated world, such pure design approach is aesthetically refreshing. That kind of design is effortless for the viewer, because the message can be seen instantly instead of searching for it through the visual clutter. Appreciation of the subtleness could serve as a counteract to the hectic, digital lives of contemporary man, where slow engagement is often neglected and replaced by a digital screen.

In most Western society, a lot is designed in a rather masculine manner; everything must be monumental, and subtleness is often viewed as a boring, imperfections as ugly and emptiness as unsophisticated (apart from the minimal design trends). From analysing the Japanese aesthetic qualities and their impact on contemporary design and society, it gave me a good opportunity to compare and reflect upon my own culture and my role as a graphic designer. I discovered similarities to my own design vision and that I appreciate simplicity over abundance and modesty over extravagance.

I would say that the core of Japanese aesthetics is ‘material poorness and spiritual richness’, whereas West is the culture of the excessive. A lot of Western design is aimed on technological development and advancement and the focus is often only on the future, neglecting issues of the present day. Technological development has brought up massive improvements onto our lives and should not be hindered by any means. However, we should move forward in a more conscious manner that would not only benefit our environment and in a way that would not make us less humane. In other words, technology should be used to enhance the quality of life without erasing the human aspects of it.

The Zen-inspired Japanese worldview seems in general more humane and nature-oriented and the design philosophy is directed towards preservation of the traditions. I can deeply appreciate Kenya Hara’s work, because he implements traditional ideas in a innovative, present and future oriented way.

Designers have the power to present new aesthetic platforms that could challenge people’s standpoints and trigger them to live more consciously and see things in a new angle and consequently enhance their lives. Designers have responsibility of being socially, culturally, environmentally, politically aware. As an example, designers could possibly embrace i.e. environmental issues in their material choices by making sustainable and ecologically aware choices and make critical designs that raise awareness. Design helps people to understand the changes in the world around us and turns them into our advantage by translating them into something that could enhance our lives and change the ways we perceive the world around, or simply just make our daily lives more exciting and meaningful.

People are in a constant search of the more complicated and impressive. In the contemporary world everything is targeted to be quick and perfect. We often fear that simple ultimately means easy, unsophisticated or unfinished and in today’s world subtle beauty is easy to get buried in the clutter and not be understood. But beauty does not only need to exist in the clean, mathematical perfections but can be found in the aspects you least expect. It just needs a different way of seeing, a new perspective on the world, and I believe design can do this.

Abstract

This research investigates traditional Japanese aesthetic values, concentrating on simplicity, and their presence in contemporary Japanese design. Despite being one of the top leading countries in technological advancement, Japan still manages to contain dominant and highly distinctive traditional features. These features are visible in contemporary society and deeply rooted in the everyday lives of the Japanese people. It is interesting that these aesthetic values are a total opposite from the Western standards where the conventional beauty is usually something monumental, extravagant and spectacular.

In Western society, the ordinary and simplicity is neglected and considered as insignificant aspects of life. In contrast, the Japanese aesthetic values find beauty in refined simplicity, emptiness, desolate and in things often considered as mundane and ordinary. It may not be normal for us to appreciate the mundane, because they lack the same aesthetic appeal that is out of the norms for us. We are taught and pushed to strive for the best and to achieve the most extraordinary results.

This paper examines what exactly makes these Japanese aesthetics so distinctive from rest of the world and why this kind of simplicity is so powerful and inspiring. With the diminishing cultural values in Japanese contemporary society and the heavy influence from the dominating Western design, are there still traces of the Japanese aesthetics in its contemporary design? The thesis will introduce Japanese aesthetic concepts Wabi-sabi, the beauty of simplicity, and Ma, which is the empty, formless beauty and examines how these are visible in the modern Japanese culture and design.The impact of these aesthetic qualities on contemporary Japanese (graphic) design is analyzed by exploring works of graphic designer Kenya Hara among other Japanese designers.

The goal of the thesis is to find new perspectives and aesthetic experiences to put the things we take for granted on a daily basis in a new light. Also, new ways in which we could become socially more conscious and aware of our surroundings from an ecological point of view will be discussed. Crucial to this research is the importance of simplicity, not only in design but also from an ecological point of view. Japan’s use of ancient ideas and strive to update them in an innovative way to be valid in the contemporary society is admirable and can serve as an inspiration to designers.

Instead of constantly searching for new perfection through focusing on technology and erasing a country’s traditions and culture, we can also aim for sustainable design solutions. Simplicity can present benefits for our society and way of living, yet we neglect it and keep striving for the most complicated and excessive. In today’s technology-saturated world, could we enhance our visual communication by examining the ancient Japanese aesthetic principles? ‘Greatness’ could exist in the inconspicuous and overlooked details.Sometimes answers can be found in the most unexpected forms.

Sources

Rock garden in Ryoanji temple

Beauty in the desolate

“Whenever I see the alcove of a tastefully built Japanese room, I marvel at our comprehension of the secrets of shadows, our sensitive use of shadow and light. The “mysterious orient” of which Westerners speak probably refers to the uncanny silence of these dark places… Where lies the key to this mystery? Ultimately it is the magic of shadows.21”

Rei Kawakubo, Commes des Carcons.

Empty

Emptiness is the core concept in Japanese aesthetics. Periäinen explains the meaning of ‘Ma’ in his book ‘Void’ by “being the pure and essential void between all things22” and the ultimate form of simplicity. Nothingness is the center and a space where things originate and evolve from.23” Ma is in the Japanese architecture, garden design, music, flower arrangements, calligraphy and poetry, and like Wabi-sabi, Ma is a way of life, not only a philosophical and artistic concept.

Simplicity in the West has existed only for a little while compared to Japan, where it has been an important part of life for more than 300 years.24” In the West however, simplicity was first introduced by the American arts movement minimalism. It began in New York City in the late 1960s and notable contributors include Donald Judd and Frank Stella.25”

Emptiness, in the West, usually has negative connotations and is linked with words such as boring, un-sophisticated and unfinished. In the East, emptiness possesses endless possibilities and is the element of ultimate sophistication. To describe the meaning of Ma, Periäinen uses the Japanese flag as an example. The flag has a red circle in the middle, surrounded by blank space. The flag does not have any profound meaning to it, but the emptiness around the red circle is open to many interpretations, a rising sun being one of them. Periäinen also describes Ma by being the pauses in speech, which make the words standout and the white space around letters that enables the shape to exist:

“It is the purposeful pauses in speech, which make the words stand out, and it is the quiet time we need to make our busy lives meaningful. It is the silence between the notes, which make the music, and MA is what creates the peace of mind we all need, so that there is room for our thoughts to exists properly.26”

The famous painting Pine Trees (1539-1610) from Hasegawa Tohaku is a great example of beauty seen in emptiness and the use of negative space. The painting consists of only a few pine trees wrapped around the mist. It is the emptiness of the mist that allows those trees to stand out and it is what creates the powerful atmosphere of the painting.

Pine Trees (1539-1610) by Hasegawa Tohaku

Emptiness plays the most important part in the living space and interior decoration of a Japanese house27”. A typical Japanese house contains peacefulness due to the predominant emptiness. The most sophisticated Japanese houses contain no unnecessary objects or decorations and is consequently free from clutter. The dominance of emptiness makes the objects present to stand out. To the eyes of a Westerner, Japanese houses may seem modest due to the sizes of the rooms and the lack of furniture. During my stay in Japan, I was surprised to see that Japanese rooms do not have what is necessary to Western houses: beds, shelves and a large dinner table with chairs. The rooms in a Japanese house are used in a multifunctional manner; for example the beds are stored away during the daytime, in order to use the space for something else. The emptiness in the houses allows the rooms to stay flexible and adapt to different requirements.

This kind of lifestyle is quite contrasting to the Western standards. It seems as we need stuff in our surroundings to fill the void and to create meaning in our lives. This can be seen especially in most Western interior design, where we have the need to cover our walls with paintings and frames and tables filled with all sorts of decorational objects. One exception of this is Scandinavian design, where simplicity, nature and the ‘less is more’ concept are the key design elements. Kenya Hara explains, that the past, we needed this kind of extravagancy to demonstrate the power of the king or an emperor, but in today’s world kings do not possess such power anymore and such ‘show off’ is not necessary.28”

Another aspect of Japanese life where this kind of refined simplicity is found is in the Ikebana flower arrangement. Hara claims: “a vessel full of something, mounted high with whatever it may be, is never as beautiful as one that is empty.29” This can be applied to the art of Ikebana, where only a couple of flowers and branches are used in a vase. Natalie Avella, author of ‘Graphic Japan’, points out that:

“The Japanese sensibility sees no beauty in a mass of flowers in a vase. The single flower loses its effect in the mass, and opulence alone is not considered a virtue in an arrangement.30”

Limited, careful use of material and space and the balance between those two in Ikebana is rather similar to the method of work of many of Japan’s most well-known designers: restrained use of text, color and line.In this chapter, I have discussed two notable Japanese aesthetic concepts. The next chapter analyses how these philosophies are used in contemporary context, focusing most specifically in graphic design.

2: Traditional aesthetic values in contemporary Japanese design

Emptiness in communication

The contemporary Japanese graphic also displays a unique mix of traditional cultural influences while pushing towards global innovation. The design values concentrate on quality, elegance and innovative thinking. The design style is focused on simple and clean design solutions, and leans towards use of natural materials. In the Western world, it is often acknowledged that modernity will wipe out cultural traditions. Conversely, Hara views design as a cultural product and that “design should aid you in tracing perceptions and objects to their origins.”30 That being said, Japanese design often uses traditional ideology successfully transforming and updating them into contemporary context.”31 Simplicity is the key design element and it is the prevailing aspect of Japanese design. It is important to note here that the term ‘simplicity’ does not imply a lack of content.

Kenya Hara explains Japan’s fascination towards simplicity and minimalism by being “the most comfortable way for Japan to face the world.32” Hara is seen as the future of Japanese design, because of his ability to express and communicate a clear Japanese design philosophy that is aware of the past and insightful to the present.”33 He applies everyday observations with reflections on Japanese aesthetics and sensitivity to his work. Hara believes that Asian countries hold a key cultural resource that cannot be found anywhere else in the world and that “lifestyle has value in Asia”. Hara said: “The Swiss have their cheese, the French their wine, but Hara’s future Japan will be based on the export of a way of life.”34

Hara’s design principles are profoundly associated with the Japanese aesthetic concept of emptiness. Emptiness is similar to the Western idea of simplicity. There are, however, numerous differences with one being the fact that in Japan it is viewed as a positive quality. Emptiness is the “possibility yet to be filled.”35 Hara’s book ‘White’ is entirely dedicated on this subject matter, white being closely intertwined with emptiness. Hara explains that emptiness is what makes people and things what they are: “reality can be understood as background noise with nothing much going on and out of emptiness would (ideally) emerge the viewer’s questions, theories, and efforts to forge independent meaning.”36 Hara believes this to be a uniquely Japanese quality. “I hope to design outside the consideration of a form”37, he explains. Hara uses a vessel to explain the value of emptiness in graphic design:

“The mechanism of communication is activated when we look at an empty vessel, not as a negative state, but in terms of its capability to be filled with something.”38

If a vessel is already filled with stuff, it cannot be filled anymore and subsequently fails to present any new opportunities. Emptiness lets the mind and its creativity wander freely. For instance, Japanese conversations use emptiness the same way Hara uses empty space in his design work. He writes about the power of non-verbal communication such as a nod or eye contact that can convey so much.

The Japanese way of communication is full of emptiness: subjects of sentences are often left unsaid and left for the imagination and speculation.39” The Japanese people see words as not always necessary in a conversation. This opposes the Western standards of communication, which is more direct. In most countries, especially in the United States, a silence in a conversation is considered awkward and the conversation needs constantly go on to avoid awkwardness. Hara views people reaching a harmony in silence to be a highly sophisticated level of communication. Listening is a crucial part of it and this applies also to design: “good communication has the distinction of being able to listen to each other, rather than to press one’s opinion onto the opponent40.” Hara explains: “Each party must work to surmise the other’s position. This mutual work eliminates three or four steps in the dialogue before the first word is even spoken.41”

Hara’s work has elements of courtesy that can be linked with the Japanese mentality of politeness and respectfulness. As he states, a good design should not always impose ideas and opinions onto its viewer; instead it should leave room for interpretation and the viewer to experience the work, also from a personal, imaginative level.42 Hara, in common with many Japanese artists and designers, uses a lack of detail and void around an object in order to leave the interpretation up to the audience. His design of the perfume bottles for the Japanese fashion brand Kenzo obeys his design aesthetics and taste; it is all about the clean, simple form. Nothing unnecessary; it revolves around the functionality of the object in its purest form. It is a good example how emptiness could be a powerful design element.

Designing for the senses

Japanese design emphasizes how an object is felt or accepted. “Hara intensifies the need to critically adjust our understanding of the senses. He challenges the simplifications that inform much present day thought concerning what could be felt, experienced, and emotionally negotiated."43

Hara states that in today’s world a lot of slow engagement is neglected and replaced by a digital screen and that our senses must be ‘awakened’ from the mind-numbing routines of our daily lives. Hara’s ‘HAPTIC_Awakening the senses’(2004) exhibition does exactly that. It focuses on the interaction between an object and human senses, stimulating and using them to change our perception of our surrounding. The exhibition consisted of contemporary designs researching the theme of perceiving senses through material choices, shape, color and texture. His motive was to design an object through which a person can sense and physically feel something.

The logo of the exhibition was letters drawn with cultivated fungus. An example from the exhibition that demonstrates this kind of awakening is the limp remote control. When the remote control is switched off, it hangs down as if it were dead, similar to Salvador Dali’s surreal painting style of the melting clock. The material used for the production was unusual and was responsive to the touch of a human. New perspective on the so-called mundane objects is beneficial, because it enables us to see things in a new light.

Defamiliarization of the ordinary

Hara states that ‘defamiliarization’ is closely related to ‘white’ and emptiness. “White moves in the opposite direction of chaos; it is the singular image that emerges from disorder.”44 He explains that when he meditates on an object, it becomes refreshingly different, as if he had just encountered it for the first time.45 When thinking about our everyday objects, we see and use them every day but yet we do not really acknowledge them and the possibilities they possess. These objects may have become too common for us, so that they have become something trivial. Hara believes that a good design creates another perspective on something and the user will “never look at an everyday object in quite the same way again”. He calls this kind of thought process an ‘awakening’; something that could deepen our understanding of objects and our surroundings. It could awaken us from the numbness of being in our daily comfort zones and help us to regain perspectives of our surroundings and the objects around us. He states: “design should make the known become unknown.”46

Hara’s designs defamiliarize every day objects by distortion and manipulating the scale or the perspective. His exhibition ‘Architect’s Macaroni Exhibition’ is a great example of that. Hara asked twenty architects to redesign macaroni that is 50 times bigger than a normal macaroni. The main research question was ‘what does macaroni and architecture have in common?’ The architects had a total freedom of redesigning pasta, which resulted in complex and futuristic designs that are unrecognizable as the pasta found in the supermarket.

Akio Okumura: i flute. Kenya Hara: Architect's Macaroni Exhibition

It is not as creative to design things representing their original form; they grab more attention when they are out of the ordinary and present new possibilities and dimensions. Surely, these designs of the pasta are too crazy and complex to be sold commercially. It does, however, make the viewer look at the ‘boring’ pasta on our plates in a new light and realize its beautiful forms that we hardly ever pay attention to. Hara explains how the ‘defamiliarization’ of an everyday object works. He talks about how numerous artists, including Yasuhiro Ishimoto47, have tried to transform ordinary flowers into something unfamiliar.

”Yet if we perceive a flower as a living entity, even in a picture, we can come closer to reading its true essence. Photographers often compete to take pictures of flowers for reasons that have nothing to do with their beauty. Rather, they desire to reach the point where they can capture the living flowers in a way that no one ever has before.48”

An object that we encounter constantly on everyday basis is likely to become so normal to us that it becomes almost invisible. Design and art can make us rediscover these objects, making them exciting again, and ultimately making daily lives more exciting. When we see an object we take for granted in an unfamiliar context or form, we suddenly start seeing it again. The ordinary objects around us may not have much aesthetic appeal at first glance, but they do play an important part on our lives and indicate things about our existence.

‘Gurafiku49 is an online magazine dedicated to showcase contemporary Japanese graphic design. Exploring the online magazine, the links to the traditional concepts are evident in many of the poster designs. For instance, the images and typography are often wrapped around empty space. Wabi-sabi elements can be seen in the hand-made aspects and playful imperfections. The influence from Western graphic design is obviously evident, but the usage of empty space, simple shapes and hand-made imperfections and textures indicate the underlying inspiration from the traditional ideals. Writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery states:

“Perfection (in design) is achieved not when there is nothing more to add, but rather when there is nothing more to take away”.50

This statement applies to a lot of these poster designs where the design elements have been stripped to the maximum; yet still remain interesting for the viewer. It is intriguing how these designs possess the opposing atmosphere to the vivid and hectic landscape of the city. Instead of being imposing and shouting the message, these posters gently allure attention. Such ‘in your face’ approach is not always necessary, when the design is able to communicate a clear visual idea. The refreshing emptiness around the typography and the images together with the pastel color palette and bold unpretentious lines catch the attention immediately and is pleasing to the eye due to the peacefulness it emits through the harmonious and well-composed design elements.

Graphic designer Koichi Sato’s posters are a good example of a mix of traditional taste together with contemporary and futuristic imagery. Graphic designer Shigeo Fukuda’s51 posters often are inspired by the possibilities that negative and empty space possess. He uses those qualities to create optical illusions. His posters portray a creative way of using negative space for his benefit. When white space is used in an intriguing manner, it transforms into foreground. “The emptiness becomes the positive shape and the positive and negative areas become intricately linked.” It is often a lack of controlled white space that produces visual noise and inharmonious design. Author Alex White supports this claim:

“Emptiness in two-dimensional design is called white space and lies behind the type and imagery. But it is more than just the background of a design, for if a design’s background alone were properly constructed, the overall design would immediately double in clarity and usefulness.53”

Dynamic white space, abstraction and removing unnecessary details are the key to sophisticated design. He states that most design education is concerned with combining and sometimes inventing bits of content and it almost always overlooks the critically important part of the design that goes unnoticed: the background spaces and shapes. White space is like the glue that holds all the other elements in place.54

Poster design by Koichi Sato

Redesign of chocolate bar

3: The value of emptiness in Japanese design and society

Sustainability and design

As seen in the interior design of Japanese houses and in Zen Buddhist ideas, Hara sees the importance of removing all the decorations and everything that is unnecessary. Clutter hides and distracts us from what is truly meaningful. This design philosophy can be especially seen in the products of Muji55. Muji’s aesthetics and ideology is directly derived from the Japanese aesthetics of emptiness. It is distinguished by its minimalism and respect towards nature. It emphases on recycling and avoids waste in production and packaging. It also emphases a no-logo policy56, implying that only a little amount of money is used for marketing and advertisement. Their design style has been described to have ‘mundanity, being ‘no-frills’ and ‘minimalist’ and also as ‘Bauhaus-style’.57

Muji’s product design and brand identity is based around the natural materials and efficient manufacturing processes. The products have a very earthly color palette and all the product labels are the same and indicate only the contents of the product. The photograph below of a man surrounded by void basically summarizes the ideology of Muji. The man on the photograph looks so small and humble amongst the vast greatness of void, which fits in with their ideology that man is not the center of the world, but equal to everything and that nature cannot be controlled; instead, we should strive for harmony with it.

MUJI advertisement, 2003, "Horizon" poster, Uyuni Salt Lake

RE-DESIGN daily products of the 21st Century’ is another of Hara’s exhibitions. It shows how daily life serves as a great source for design.58 These ordinary objects include toilet paper, tea bags and matches. The goal was to redesign familiar objects in a unique way to create new experiences and ways to use them. Some of the objects were made to make our daily lives more beautiful and our daily routines more enjoyable. Some objects did the opposite; in fact some became harder to use in order to convey a serious message.59 This happened with the redesign of toilet paper, designed by Shigeru Ban60: the hole in the paper roll was cut in a square shape instead of a circle, which made it difficult to roll and in the end you consume less toilet paper. Making a little but substantial alteration to the design, changed its purpose: instead of being just a toilet paper roll, it now serves as a reminder of our wasteful and unsustainable habits and that we should cut down and slow consumption of paper.

Matches were redesigned in a way that they look like real twigs from a tree to remind us of diminishing forests. These redesigned products are all about preservation and renewal by making simple, yet thoughtful alterations. The chocolate bar may seem at first just like an ordinary cute pattern, but because of the cut of the pattern, you will end up eating less chocolate, resulting in fewer consumed calories. This reminds the audience to cut down sugar consumption, because of the numerous underlying health hazards.

In his book ‘Designing Design’ Hara elaborates on the importance of emptiness in both the visual and philosophical traditions of Japan and its application to design. The title of the book means changing the traditional into totally new ideas, such as changing its original design, including shapes, functions and concepts.61This creates a new way to face our daily life and daily products. These works are about the products of daily life, like square tissue and redesigning pasta. The realistic looking silicone molded ‘cabbage bowls’ by designer Yasuhiro Suzuki peels off leaves that become its own functional bowl. Designers should face the real needs of our daily life that could help them to find the real meaning of contemporary product design. In order for us to make an aesthetic judgment of an ordinary object, we must first experience that object in a different form, giving it greater significance than the other, similar, objects around it.

Yasuhiro Suzuki: Cabbage Bowls

Naoto Fukusawa’s62 juice box package design portrays a new imaginative approach on packaging design. The design imitates the skin textures of real fruits. They bring out a new simplistic, refreshing take on packaging design that unquestionably stands out from the rest of the food market. The simplicity of the design puts the emphasis on the function and essence of the object. It also makes us face the reality that we tend to forget or simply ignore where for example our food comes from and therefore we could create more awareness with more design approaches like this. According to Hara, design should not aim for the short-term response, but focus on the long-term purpose: “if every designer had this kind of pursuit, the quality of modern designing could be improved. When the public understands designers, the design industry of modern products could have a bigger market.”

Naoto Fukusawa: Juice Skin

The word ‘Re-Design’ includes the meaning of recreating the definition of normal products. Hara encourages designers to improve the value and functions of these daily products in order to find the purpose of designing. Hara uses the redesigning of a cup as an example: “designers can follow the ideas of original function, which is holding water but not the current structure and trends. As long as designers could produce items that can be filled with water, these products could be called ‘cup’.63” Our visual environment that we interact with every day plays an important part on our lives morally and socially.

Hara’s designs combine active cultural imagination with a pragmatic engagement in everyday life. Design can be used to communicate a country’s values, history and possibilities. It can manipulate reality in a way so that it brings a new perspective to the viewer. Taking the ideas of simplicity from the East and adapting it to our way of life could enhance not only the quality of our lives but our surroundings as well. An example of a mix of Eastern philosophy with Western design is demonstrated through the Rings-stools designed by Nao Tamura for Artek. Nature has drawn the ‘yearly rings’ of each tree differently: the thick rings indicate good years and the thin, the bad.64 This is a unique approach of using natural elements in a contemporary context.

'Yearly rings' chair, Artek

Ecological value of emptiness

Emptiness does not only present positive qualities within the arts, design and architecture, but has a massive potential in improving our environment that is facing some of the most serious issues of human history ranging from climate change to over population. According to Periäinen, emptiness creates possibilities for an ecologically sustainable coexistence of man-made environment and nature. “Let us think about those additional 7 billion people + the continuous economical and material growth desired by those already living.66”

Periäinen also says:

“Void empties thoughts of routines and prejudices and outgrown value structures. In Eastern thought the emptying of the mind is a prerequisite to grasp universal truth or enlightenment. It could help the West, as well, to embark upon a new and more natural era.67

He wonders why so little emptiness has been interpreted in the Western lifestyles and mentality compared to Japan. In fact, West is known to be the culture of the full and excessive. Using empty space would not only be important for the restore and maintenance of the ecological balances, but also for the development of a more natural ways of living. This is because emptiness in practice eliminates material objects and borders. Meanings that emptiness offers a really powerful tool to decline materialism, thus easing the pressures put on living nature.68 The Zen Buddhist thoughts teach people to aim for ‘non-material emptiness’. Periäinen said:

“The non-material emptiness and the balance between the void and material could perhaps again be achieved by combining the old wisdom of the East with the technological know-how of the West.69”

This could be applied for example in the sizes of produced objects and careful choice of environment-friendly materials. Periäinen states that “In Japan, seeds have also been sown for Western industrial product development: the size or volume of several gadgets, their amount of materials and components, is constantly reduced.”70” Like in Japan, the Nordic countries have also adapted a simplified and reduced design language that has become part of their country’s identity. This design language has not only aesthetic value, but is used in a position of more prominent ecological importance.

Designers today are familiar with the current tide that adds value to the creation of something new. I believe that design should seek for innovative, forward-thinking and experimental solutions. However, we have to do it in a conscious way that is aware of the currents of our world and in a way that we do not end up erasing the traces of our past and everything else standing on the way. To my understanding the Japanese sensibility is probably more adjusted towards preservation rather than only aiming for something completely new. We could make a change by reducing the size of gadgets and minimalising waste in production and making conscious choices for materials. To conclude this chapter, simplicity is not just an aesthetic concept but possess endless possibilities and solutions to enhance our lives and the environment. We have now researched simplicity and emptiness from a traditional side, in contemporary design context and from ecological point of view.

Conclusion

The starting point of this thesis was a personal fascination and curiosity towards Japanese culture and design. Through this research I came to find the real underlying fascination and motive for my interest. I realised that I can relate to the Japanese values and strongly believe this is because my home country Finland shares a lot of similar values as Japan, such as appreciation of nature, quietness and simplicity. Just like in Japan, awkward silences are acceptable and one does not need to talk all the time just to fill the silence. Finnish design is also world famous for its ‘whiteness’, simplicity and use of natural materials and nature as the subject matter.

In fact, Japanese simplicity seems to be comparable to Western design principles of ‘less is more’; especially seen in Scandinavian and Nordic design. The major difference between them is that simplicity has existed far longer in Japan and is implemented into nearly every aspect of their society and culture. The lifestyle and aesthetic values in rest of the Western world are quite contrasting to the ones in Japan. Another major difference is that in the Western world emptiness is always viewed as something negative. Western world seems to have a phobia of emptiness where as Japan has a phobia of clutter. Emptiness in Japan means a new beginning; the origin of everything and full of possibilities.

The traditional Japanese views on beauty are also much different to the ones in Western society. Japanese values suggest a more subtle beauty that is imperfect, evanescent and rust. In design and visual communication, the focus seems to be on listening as a way of communication instead of ‘yelling out’ or imposing the message. In my opinion, in today’s consumer-saturated world, such pure design approach is aesthetically refreshing. That kind of design is effortless for the viewer, because the message can be seen instantly instead of searching for it through the visual clutter. Appreciation of the subtleness could serve as a counteract to the hectic, digital lives of contemporary man, where slow engagement is often neglected and replaced by a digital screen.