Research question

The externally depoliticized appearance versus the internally power-laden nature of each space. - How the mechanisms of power have domesticated internet data and wildlife in the DMZ?

Boundaries are often depicted as walls, but in truth they are far more intricate. A boundary is not simply a line or barrier; it marks where I end and someone else begins. At once, it performs contradictory functions: protection and separation, connection and disconnection. Within this ambiguous duality, we experience both the sense of security that boundaries confer and the anxiety they inevitably generate. Such a dual state of mind formed the backdrop to my upbringing in Seoul—the capital of the world’s last divided nation—at the tail end of the Cold War in the 1990s. In everyday life, the calm and the unease brought about by boundaries would unexpectedly intersect time and again. Here, I want to delve into the truth behind these boundaries.

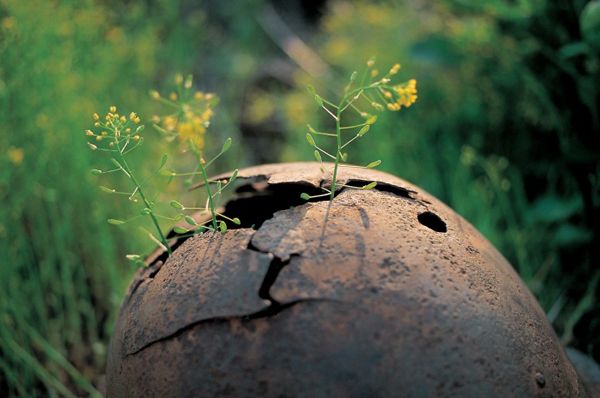

In Korean society, the existence of boundaries is sharply illustrated by the Military Demarcation Line that cuts the peninsula into two. After the Korean War ended in 1945, negotiations established a buffer zone two kilometers to the north and two kilometers to the south of this line, creating what is known as the Demilitarized Zone (United Nations Command et al., 1953, Article 1). A The mix of security and anxiety surrounding this boundary goes beyond the mere geographical space of the DMZ and reflects broader political and social circumstances in Korea (Park, 1997).BIn fact, the DMZ carries two faces: the notion of stability and peace, promoted as a “pristine ecological treasure,” and the specter of threat and conflict, manifested by ongoing military tension and rigorous surveillance (Song, 2022.). C As fears of nuclear armament and armed clashes intensify, the DMZ’s “peaceful and ecological” image paradoxically becomes more prominent. Yet behind this green curtain lies the undeniable legacy of war, with layers of remnants and scars accumulated over decades.

I encountered this green curtain—long dormant in my subconscious—quite unexpectedly during a morning stroll in park in The Hague, Netherlands. Amid the greenery path barely visible through the dense fog, a tall stiff stem rising from the ground with its tip slightly bowed heads out; trying to blend in among real plants mimicking their appearance. This drooping thing turned out to be an unused fiber-optic internet cable. Ironically, however, it was far more ubiquitous than any actual vegetation covering the entire globe internationally.

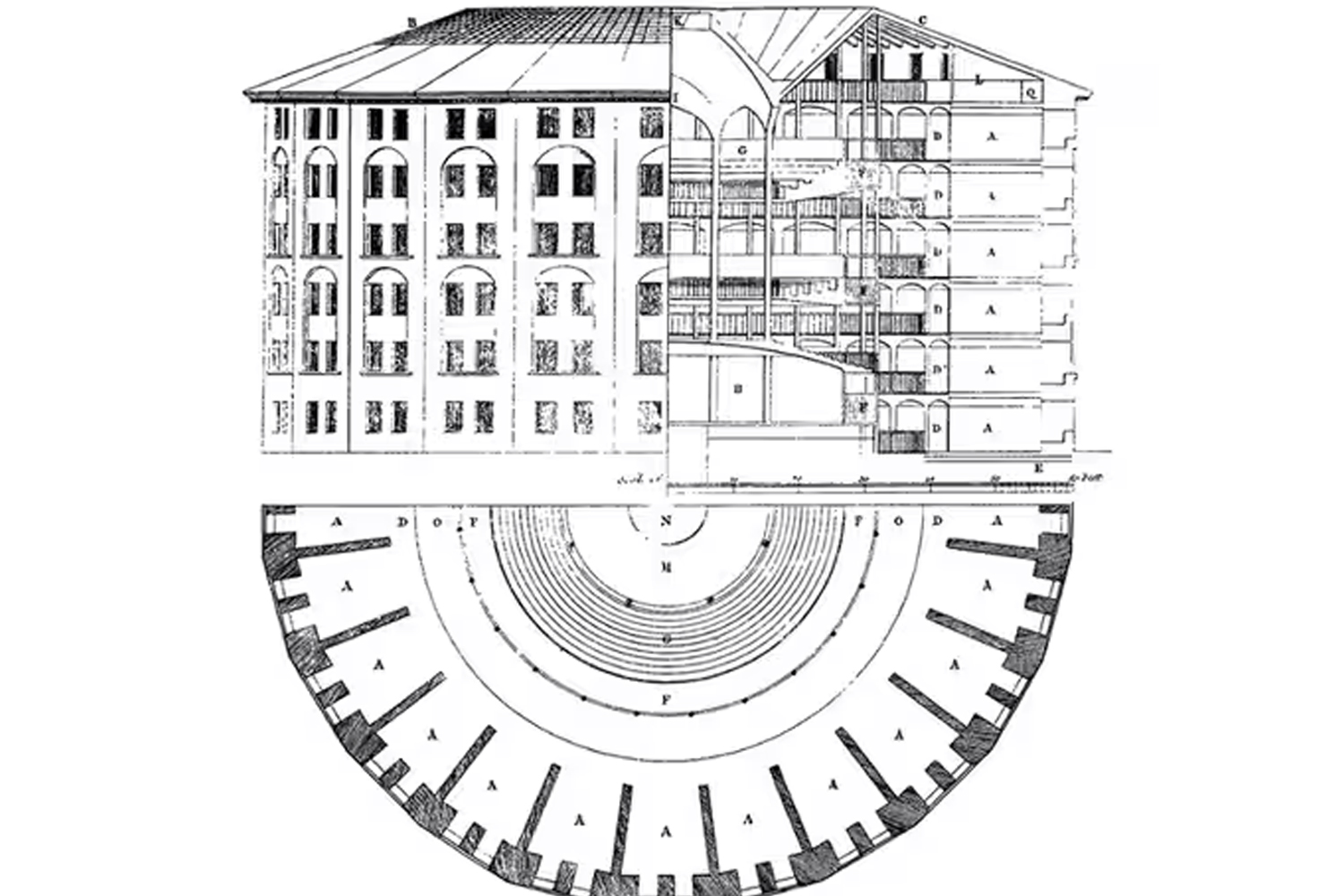

In the Netherlands, fiber-optic cables sprawl beneath the ground like roots of a vast living organism. These multi-colored cables reflect government policies that assign specific colors to certain internet service providers on each street. Following these roots to their underground hub, one eventually reaches massive data centers housing super-computing machines that emit intense heat. Because these centers handle sensitive tasks of classifying and analyzing data, they remain highly confidential, with even company employees often unaware of their precise locations or identities.

For some thirty years now, the Internet’s “warm blessing” has become so integral to our lives that it might as well join sunlight and water as a basic component of our being. On average, people spend over 70% of their day online, though they often do so without even realizing it. Shoshana Zuboff (2019) warns that this deep digital dependence has spawned a new power dynamic known as “surveillance capitalism,” which collects and commercializes human behavior and data without restraint, rapidly Infringing on the entire world through virtual, rather than physical, borders (Zuboff, 2019, p. 21).D The Internet may appear to unify the globe, yet in practice it is perpetually segmented by national laws, corporate algorithms, and data regulations (Nissenbaum, 2010). These “digital boundaries” not only determine who has control over personal data but can also restrict access itself for some users.

Ultimately, the DMZ as a physical boundary and the Internet as a digital boundary share an underlying pattern: on one hand, they offer safety or convenience; on the other, they obscure a subtle infiltration of power. Just as the Korean government and media promote the DMZ as a “pure, untouched ecosystem,” big tech corporations market their platforms as open, participatory spaces. Yet the more concealed a domain is, the more deftly power weaves its influence (Foucault, 1979). The process by which governments and big tech firms craft specific narratives that citizens or users then “voluntarily” embrace aligns with Michel Foucault’s concept of “governmentality.” In much the same way the DMZ never fully escaped the debris of war or its surveillance apparatus, our supposedly boundless Internet similarly harvests consumer data as a vast resource for control.

It is this notion of “boundaries” that anchors my investigation. Though the boundary between North and South and the boundary of Internet privacy appear to be two distinct realms, both harbor a certain ambiguity that simultaneously evoke both stability and unease. As a Korean, raised amid the tension of a national divide, and as a modern Internet user who confronts the precariousness of digital privacy each day, I want to explore these two settings in tandem. The foggy edges of these boundaries may threaten or unsettle us, yet they also open up the possibility of transformation. However, the moment we romanticize these boundaries as “pristine nature” or a “free network,” the underlying power and our shared responsibility become ever more difficult to perceive. Hence, this paper illuminates the unsettling and dual nature of boundaries, revealing the hidden workings of power behind them, while pondering how we might reconceptualize and rebuild such boundaries for ourselves.

This thesis is divided into 4 chapters. Chapter 1 examines how the DMZ came to be recognized as both a zone of peace and a zone of war, and sheds light on the ecological system of the DMZ, where elements of "violence" - such as land mines, invasive species, and herbicides - have co-evolved with the local flora and fauna. Chapter 2 focuses on the concept of the 'digital DMZ' and shows how the physical borders - not only Korean border but also international borders - have transformed into digital borders. Chapter 3 examines the early days of the Internet and the evolving discourse of data on the Internet in an era of hyper-connectivity. It explores how the original vision of the Internet - as an open and decentralized space - contrasts with today's networked reality, where artificial intelligence and big data can fuel a form of "data colonialism" that turns the Internet into a revealing mechanism of surveillance and control. Chapter 4 argues that the Internet is becoming another digital form of the DMZ in the Foucauldian concept of governmentality, which guides how people think and act, and closes with thoughts on the alternatives we might pursue.