PROLOGUE

In this story, we will be tracing the origins of life on Earth to its material beginnings and

traveling down evolutionary routes, wading through entangled histories, skipping some parts and biting into

others, weaving human narratives in with more-than-human accounts and seeing where they overlap,

where they complement each other and when they don’t, where they diverge and when they were forced apart,

what’s left behind, what to do, which steps to take, how to weave them in again.

“The stories we are told shape the way we see the world,

which shapes the way we experience the world”

(Jensen, 2009).

A BRIEF HISTORY of YOU, ME & EVERYTHING

GENESIS

It’s most likely that you

would consider yourself as a member of the genus Homo Sapiens. If so, then you’d probably have some

sort of a body, and a skeleton to hold it in place. Your body would contain living cells and

extracellular materials, which would be organized into tissues, organs, and other systems, and amount to an

impressively expansive organism. You’d probably have features which you’d use to sense the world;

perhaps a tongue, some skin, a pair of ears and eyes,

and an uncharacteristically large brain to make sense of it all. As a mammal, you’d presumably

possess mammal-like qualities, such as hair & mammary glands (Lotha et al., 2000). Given that you are in

fact human, you’re not all that different from earlier instances in the human lineage, and though

complex, your bodily system is akin to many other organic lifeforms

(Rafferty et al., 1998). You share DNA with your fellow Earth-kin, and some more than others. You share 99.9% of your DNA with

another human, 98.8% with chimpanzees, 97.5% with mice, 94% with dogs, 80% with cows, 60% with

a common fruit fly, and more than 50% with a banana

(Ang, 2021).

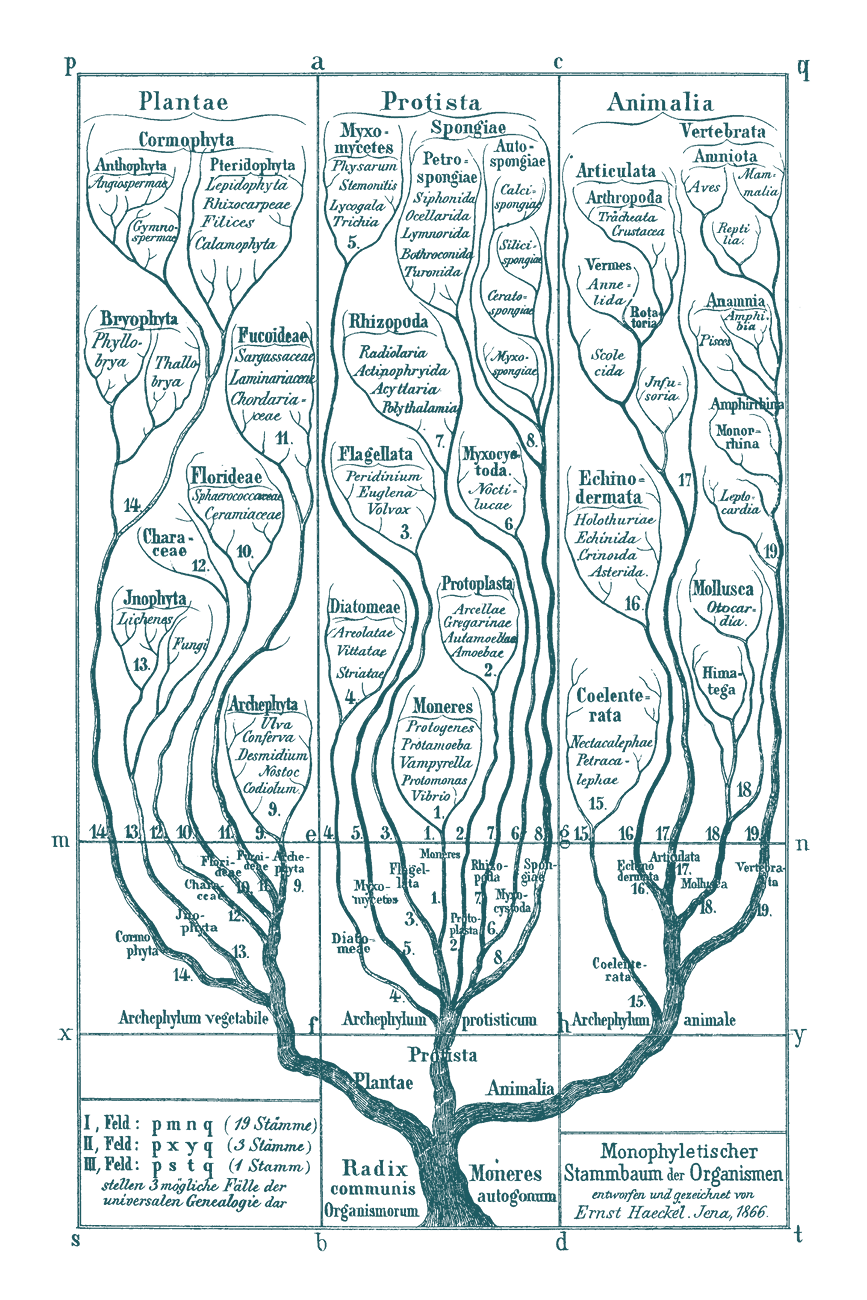

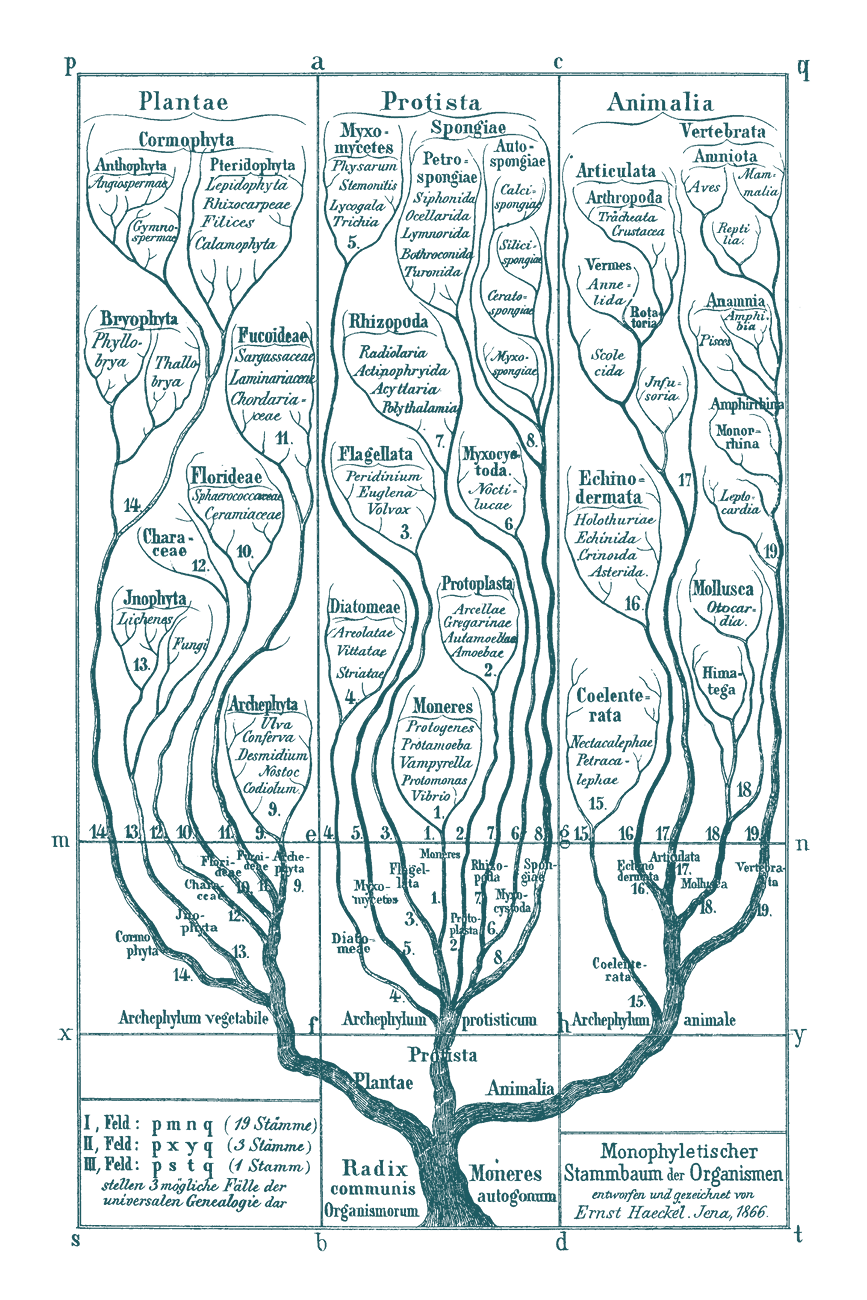

If you’d like to trace your genealogical history further, you would eventually find yourself on the

ocean floor some 4.2 billion years ago, in a single-cell bacterial organism (or group of organisms)

presently titled as LUCA, or the Last Universal Common Ancestor of all life on Earth (Wade, 2016).

It’s becoming was quite remarkable, as it was brought on by a series of ecological events caused by

the impact of our moon colliding with Earth, which converted the surface of our planet into a bed of

boiling lava, turned water to gasses, and carbon to atmospheric carbon dioxide. Only when Earth had cooled

down significantly enough to contain liquid water–and said water interacted with magma erupting through

the ocean floor–were the ideal conditions generated for LUCA, your ancestor, to emerge. LUCA was not the origin of life on Earth, but rather the emergence of carbon-based life

as we know it today[1] (Fox, 2024).

With the shifting conditions of the ecosystem and increased flow of energy and minerals, LUCA

further evolved into different types of organisms: some plant-like and some animal-like: soft-bodied

multicellular organisms with nervous systems, guts, muscle tissues, and traces of cholesterol

(Mileham et al., n.d.). Just like you, they could move, feed, digest and reproduce. An increase in oxygen led to their development of eyes & spines, and only

when calcium, phosphate & other materials got added to

the primordial soup, could they armor themselves with teeth, claws,

shells & skeletons. Each time the conditions changed, they changed with them, and every iteration generated a new

iteration (Fox, 2024). All these iterations shared (and share) a crucial dependence on the cyclical flow of

energy and minerals, where our bodies capture a portion of this flow at birth, release it when we die and

transform into different sets of materials. From plants to herbivores, to carnivores to plants

again. In many ways, the stability and resilience of

ecosystems is rooted in this constant circulation of biomass and flesh (de Landa, 1997).

1. You as the reader of this thesis.

2. You contain the same organ system as nearly 100% of vertebrates alive today (mammals, birds,

reptiles, amphibians, fish), and some with invertebrates (insects, mollusks, arthropods) (Mileham,

R.,n.d.).

3. Earthkin refers to the assemblage of all organic species and lifeforms on Earth, a term that was

popularized by eco-feminist scholar and philosopher Donna Haraway.

4. Earth is 4.5 billion years old.

5. LUCA’s descendants can be grouped into two domains of cellular life: prokaryotes (simply celled

organisms like bacteria & archaea) & eukaryotes (all forms of complex multicellular life) (Lambert,

2024).

6. All known life on Earth is carbon-based, including you (Fortey, 2025).

7. Referring to the oxygen levels in the ocean.

8. More like washed into the soup, due to a major rise in sea level, which brought life-sustaining

materials from land to sea (Fox, 2024).

9. The primordial soup (also known as prebiotic soup or primitive broth) is a “generic term that

describes the aqueous solution of organic compounds that accumulated in primitive water bodies of

the early Earth as a result of endogenous abiotic syntheses and the extraterrestrial delivery by

cometary and meteoritic collisions, and from which some have assumed that the first living systems evolved”

(Bada & Lazcano, 2002).

10. And fungi, of course.

SYMBIOSIS

As fleshy lifeforms and biomasses ourselves, we too, partake in this type of energy exchange, which

is often referred to as a food chain. There are many ways in which energy circulates through life-systems

on Earth, and there are many types of food chains. When they overlap–and form a system of interlocking

chains–we can call them “food webs”. The interaction between individual members of these organic

systems, and with inorganic systems, is called an ecosystem. “Ecosystems are not random assemblages

of species, but self-organized meshworks in which species are interconnected by their functional

complementarities: prey and predator, host and parasite” (De Landa, 1997, p. 106). Since all

lifeforms belong to some ecosystem, they’re practically everywhere.

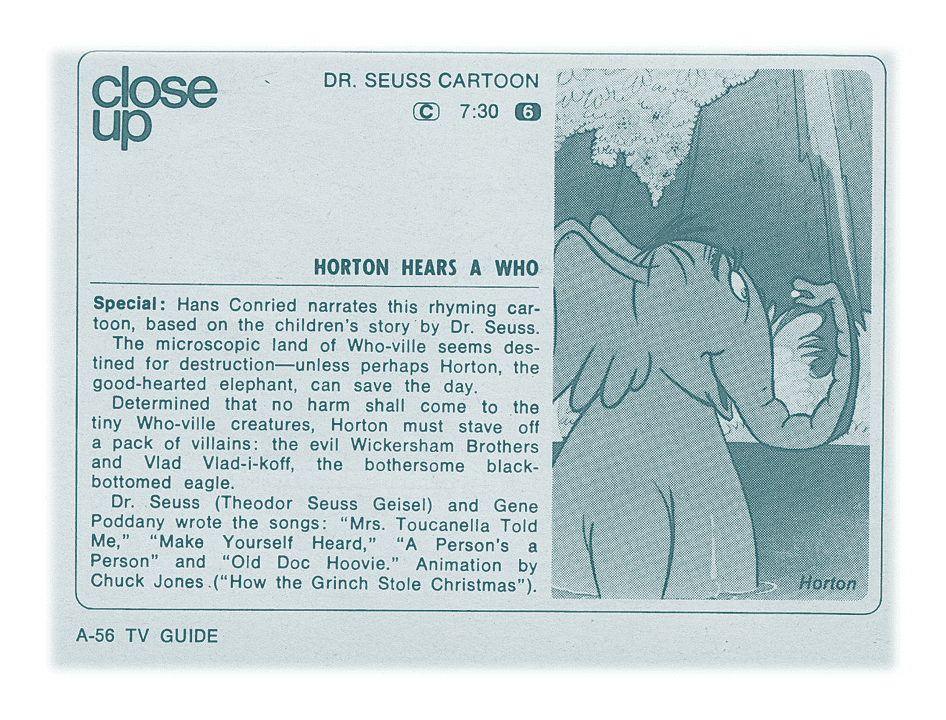

There are rich ecosystems existing on your skin and whole societies in dust particles. This is

cleverly demonstrated in Dr. Seuss’ fable Horton hears a Who! where Horton, the Elephant and protagonist of

the story, finds a speck of dust and learns that it carries a whole biome of its own[2] (Seuss, 1954). Inside these biomes and ecosystems, its agents engage in intimate relationships with one another, which are called symbiotic relationships. When

all species involved benefit from these interactions, we call them mutalistic relationships. Wolves and ravens are a good example of this type of

dynamic. In these mutualisms, the ravens alert the wolves if a prey is in sight, which the pack attacks, and the

ravens get to feast on the leftovers (Bryden, 2023). Similarly, Yucca moths lay their eggs in the seedpods

of yucca plants. The plant gets pollinated, and when the larvae hatch, they have a plant to snack on

(Encyclopedia Britannica, 2025). There are many documented cases of human and more-than-human mutualisms, such as humans collaborating with whales

and dolphins in locating and hunting fish, where the sea-bound ones typically did most of the finding and got their

share of the catch as compensation (Truscott, 2022); or the long-standing mutualist relationship

between humans and cats.

Though built environments, such as cities and towns, are by default excluding in the types of

lifeforms and natures allowed to persist inside of them; and consequently lacking in variety of organic

systems, they are still teeming with life in overlapping ecosystems, and every small weed that grows against

the manufactured landscape contains a rich life of its own. The built environments can also be

considered ecosystems themselves, both in relation to its human and more-than-human inhabitants, but also the

biomass that circulates through them to sustain said inhabitants. Cities and towns engage in

parasitic relationships with their rural surroundings, which they use to produce said biomass and other forms

of energy (de Landa, 1977).

11. Ecosystems vary in size: some are small enough to be contained within a single droplet of water,

while others are large enough to encompass entire landscapes and regions (Encyclopedia Britannica,

2025).

12. A biome is the largest geographic biotic unit, a major community of plants and animals with

similar

life forms and environmental conditions (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2025).

13. An agent is a being with the capacity to act and make decisions. It’s anyone or anything with

agency (or free will).

14. A parasitic relationship is when one species benefits and the other one is harmed, and a

commensalist relationship is when one side benefits and the other remains indifferent (Encyclopedia

Britannica, 2025).

15. Coined by ecologist and philosopher David Abram, more-than-human refers to the qualities or

attributes found in nature which include but exceed those of human beings: for example, sentience,

emotion, intelligence, purpose and agency. By using the words more-than, instead of other-than or

non-, it challenges human-centric narratives when writing about more-than-humans (Abram, 1996).

YOU as NATURE

There are incredible amounts of diverse lifeforms currently existing in entanglement with one

another on Earth. More than two million existing species have been named and described and many remain to be

discovered. These organisms are also as varied as they

are many: on Earth you can see bacteria living in hot springs, fungi thriving on ice masses, algae in saline

waters, spiders on top of the Himalayas, and giant tube worms in hydrothermal vents on the ocean

floor (Ayla, 2025). On both collective and individual levels, these lifeforms physically embody their

evolutionary heritage, not only in their DNA and their structure but also the very materials they’re

made of. Life on Earth is still assembled from the same recycled materials as it started with: some

carbon, some calcium, phosphate, and other materials (de Landa, 1977). That being said, their

structure is maybe

even more interesting to look at, as it’s quite the peculiar phenomenon: The way in which these

bio-materials flow, grow, and physically manifest themselves has a habitual tendency to follow the

same type of formula:

a single line that splits, which splits again and again and again. It’s nature’s most efficient

route for growth and distribution of energy: a mathematical formula called fractals (Pearce, 2024).

These self-similar branching patterns can be found everywhere: You can notice them in flowers, trees

& plants, in Earthly weather systems and the cosmos, in mountains, rivers, waves and coastlines

(ibid.). You can also see them in the structure of your body: in your veins, your skin, your lungs & kidneys,

your brain, nervous system, and in the rhythms of your heart; in your microbes and molecular

structure, and in the arrangement of your DNA. The branching pattern that divides the deltas is the same as the

subdivision of your veins; the neural networks in your brain look just like stars in galaxies; and

your lungs are like a branching tree, whose cross-section resembles your fingerprint.

You can recognize these shared geometries in your fellow homo sapiens, your fellow mammals, fellow

lifeforms and all other organic systems that surround you (Neronha et al., 2019). As relatives,

we’re interconnected and intertwined–and if you look closely, you can see yourself in the other & every

living thing in every living thing[3]. You might even come to the conclusion that not only do you

resemble nature, but you might in fact be nature.

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour”

(Blake, 1863, pp. 55-56).

16. Currently estimated at around ten to thirty million species (Ayla, 2025).

17. Or our structure.

18. Fractals are one of many universal formulas that guide the structure of our universe, along with

the Fibonacci sequence, the Golden Ratio, Pi (π), Euler’s Number (e), and more (Patra, 2018).

19. Though many have observed and described the fractal phenomena, fractals were officially

discovered by mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, who described them in his scientific casebook or manifesto,

titled The Fractal Geometry of Nature. “I coined fractal from the Latin adjective fractus. The

corresponding Latin verb frangere means “to break:” to create irregular fragments. It is therefore sensible—and

how appropriate for our needs!—that, in addition to “fragmented” (as in fraction or refraction), fractus

should also mean “irregular,” both meanings being preserved in fragment” (Mandelbrot, 1977).

20. The first description of a fractal pattern in nature might have come from the Renaissance artist

and scientist Leonardo da Vinci, who noted that “All the branches of a tree at every stage of its height

when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them]” (Hennings & Lynch, 2024).

COURTSHIP RITUALS, NEUROSCIENCE

& ORNAMENTING as SELF PORTRAITURE

COURTSHIP RITUALS+

As at least an agent of nature, you have been through

millions of years of evolution and taken part in

countless cycles of flows of energy & minerals (de Landa, 1977). In a single lifetime, you likely

participate in certain rituals or life practices that have proven to sustain you and your cells until your timely demise and the next cycle begins:

You

try to mind your water

intake, you scavenge for nutrients that would sustain you , you might rest in some kind of a nest or

shelter, and you might engage in courtship rituals. The bearded vulture, for instance, uses

cosmetics to

enhance his status within his society. He rubs red clay into his feathers to signify to his

prospective

partners that he simply must be a great hunter since he has all this time for makeup (OConnell,

2014).

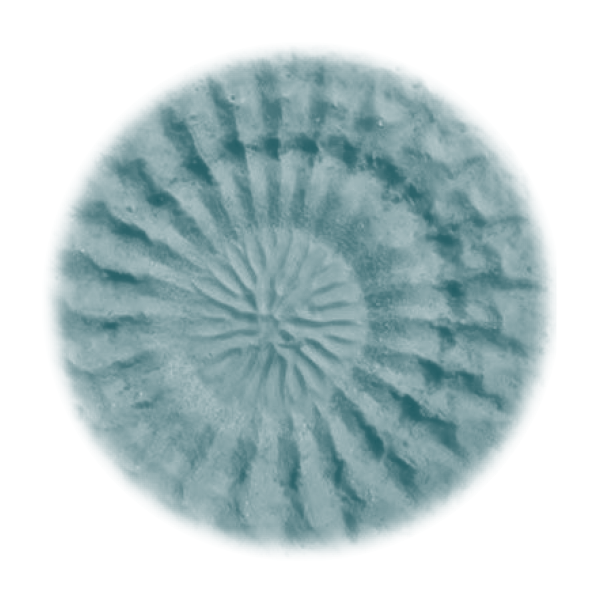

Similarly, the white-spotted pufferfish spends ages creating intricate sand decorations on the

bottom of

the ocean in hopes of attracting a mate that would appreciate his craftsmanship (Safi, 2023). There

are

plenty of animals that engage in similar rituals and many who lean into the art of decorating one’s

spaces, e.g. through collecting precious materials. Crows, ravens and bower birds are all devoted

collectors (Lotzof, n.d.).

Decorating our habitats is often a way to signify to others a certain status or agenda. You can see

a

clear example of this by looking at religious monuments in human societies: which are often

plastered

with all sorts of signage and symbols to broadcast and emphazise their religious dogmas (Jason,

2025).

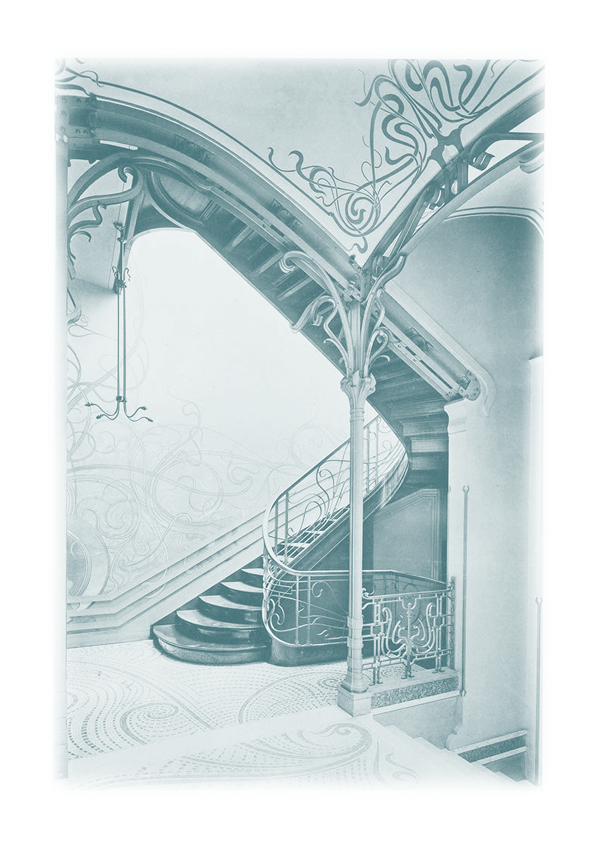

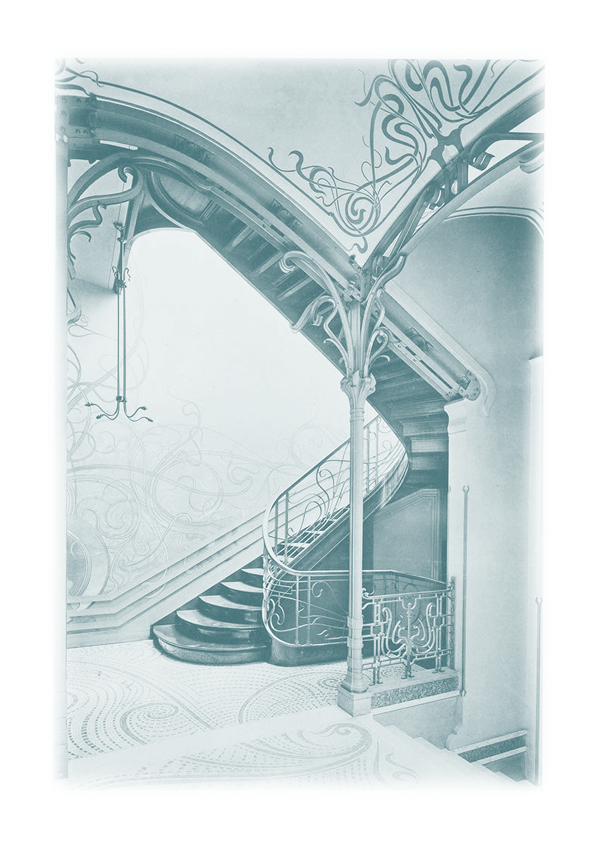

When looking at other sites, such as achitecture in built societies of the Global North, we can see more ways in which status is promoted. In

recent history,

wealth is often expressed through the size and location of a building, and quality of materials

used.

Before the onset and effects of Modernism, it was often expressed through craftsmanship and

complexity

of the construction, and often times through décor and ornamentation.

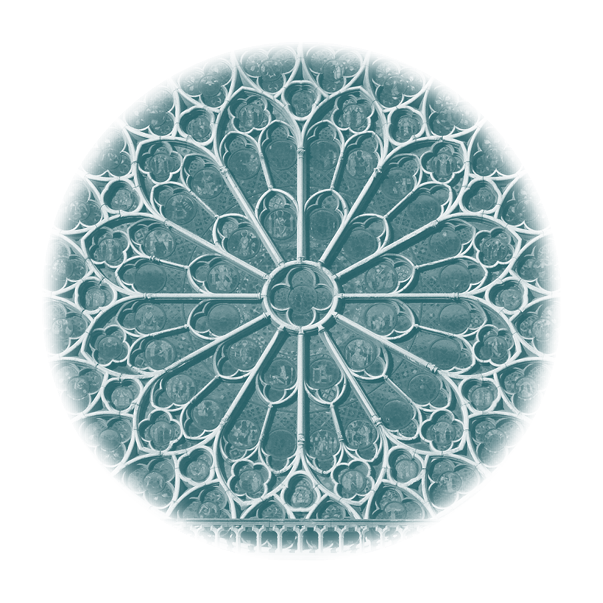

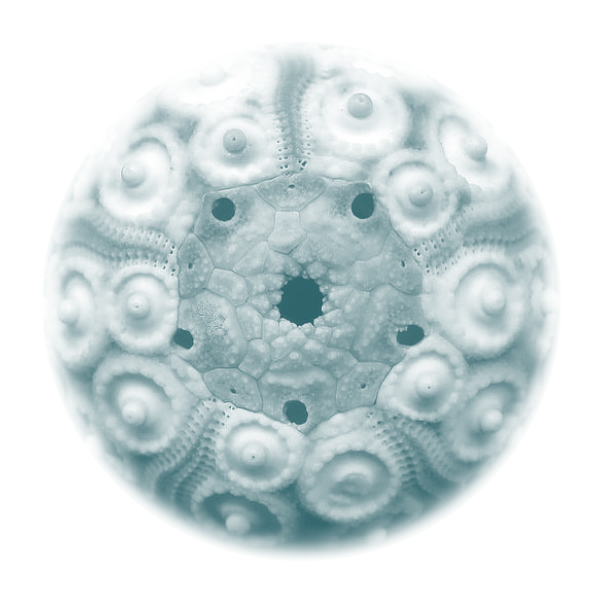

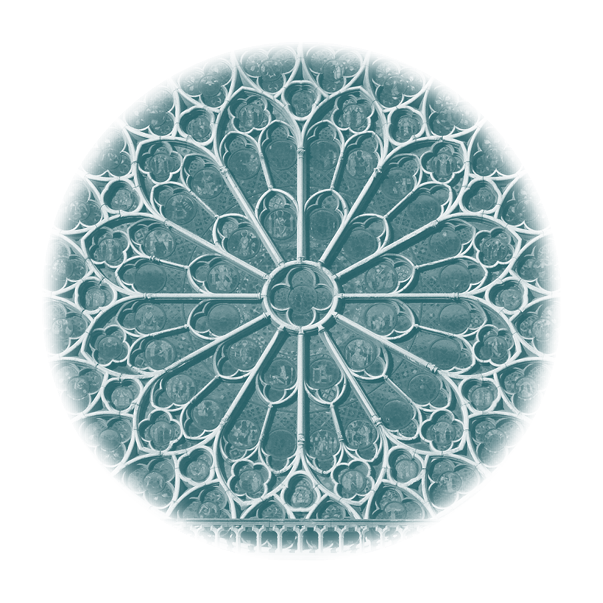

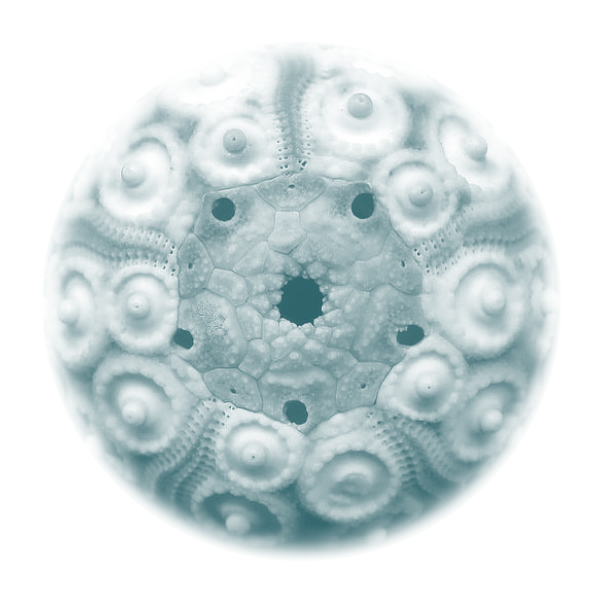

A common motif was nature; either as direct representations of a natural subject or more indirectly

so;

as shapes and constructions following the signature branching patterns of nature. Ornate ironwork

can look like branching trees or twisting vines, and rose windows in churches[5] often resemble the

structure of sea urchins[6] or the insides of flowers. They also look like the sand-art of the pufferfish[4], which

could itself be a rendering of a leaf or a halved kiwi.

21. As a human, as a lifeform.

22. Often found in grocery stores these days.

23. The Global North is a term used to describe the industrialized nations in the northern

hemisphere, which are often times the overall benefactors of global capitalism.

ARCHITECTURE & NEUROSCIENCE

It‘s worth noting the irony of post-embedding imitations of nature into built environments:

Stripping the natural landscape of its organic materials and using them to build said environments, only to

reincorporate them as natural motifs in ornamentation... Perhaps the popularity in the use of the

natural motif was in some way an effort to replace the nature that was lost, maybe in some sort of

ancestral self-remembrance, or maybe because they

simply found it beautiful. It certainly evokes a lot of questions. If it was because they found it beautiful, is it because it

depicts nature and we find natural elements beautiful? And if we find natural elements beautiful, is

it because we resonate with them? And is that because we see ourselves in it? If we are nature, do

depictions of nature count as self-portraiture?

Thankfully, there’s been substantial research done on environmental psychology and neuroscience in

the

last years, and some of its findings could potentially shed light on our inquiries. Scientists have

studied human perception of fractals and made the link between our evolving in a rugged, bumpy and

fractal landscape, to an inherent and familiar appreciation of the fractal form or formulas

(Austigard, 2023). When applying this to the designed landscape, they also found that people’s

pleasure

in looking at built environments correlates with increased complexity of silhouettes of objects and

buildings. Increased complexity also aids in our wayfinding and processing of these landscapes,

since

detailed and diverse environments help us better understand and navigate through them (Stamps,

1999).

Humans have also proven to be preferential towards symmetrical and repetitive forms, which are

characteristic across organic subjects and natural environments (Robles et al., 2020).

24. Referring to humans living in richer natural ecosystems.

25. “There’s a surprising tendecy towards fractals being in the range of 1.3 to 1.5 (D=1.3-1.5),

everywhere. From molecules to planetary systems. The fractal dimension that generates the most

pleasure in people is between 1.3 and 1.5 (D=1.3-1.5), which is not a big surprise, because we are, through

evolution, adapted to functioning well in this environment. It’s only natural that this is what we

find beautiful” (Austigard, 2023).

US in the ANTHROPOCAPITALOCENE

The OTHERING of NATURE

For most of our history, humans (more or less) saw the natural world as a vibrant organism, where

the

human was only one aspect of the organism’s overall functioning, and engaged in non-hierarchical

relations with other members of the group. Rapid

acceleration in

sciences in Western Europe in the midle of the previous millenium caused a profound (and lasting)

shift

in how we view and situate ourselves within the natural world. During the Enlightenment and with the

Scientific Revolution, the organism had become more like a machine, with parts to be taken apart and

studied (Pierre

et al., 2019), while the active landscape got demoted to a background of human activities (Tsing,

2015).

This proved to be the beginning of our (conceived) separation from nature. “Perhaps this was an

inevitable outcome: By seeing the natural world as something to be held at arm’s length and studied

objectively, we removed ourselves from our own picture of nature” (Kosinski, 2020). We no longer saw

ourselves within an unbounded and uncontrollable cosmos, the complex and mysterious, magically

enchanted

and larger-than-human organic world, but rather as governors of a quantifiable, controllable,

exploitable and commodifiable resource. As Earth-centered values were replaced with humanistic ones,

the Western human man was put on the very top of the hierarchy. Phenomena deemed opaque or irrational

were increasingly devalued in this new rationalist world; such as the natural, the spiritual, the

emotional, and the female. Some argue that this is when Modernity began (Pierre et al., 2019) and even some

that this marked a new chapter in our geological history (Demos, 2017).

In the first chapter, we briefly mentioned the parasitic relationship between built societies and

their rural surroundings, which they use to supply their energy and sustenance. This relationship creates

a power imbalance between its members, where the agents of said rural surroundings become the

provider; and in the built society, the consumer (de Landa, 1977). Who gets to play which role is determined

by colonialist and imperialist forces–inspired by humanistic values inherited from the Scientific

Revolution–which decide what parts of the landscape should be considered resources, and what parts

can be inhabited. These systems usually and unfortunately, place the Global North at the top of the

hierarchy while the Global South

operates as their fuel system. More often than not, this leads to ruthless and exploitative

extractive practices of these landscapes and their inhabitants, which results in forced labor and ecological

catastrophes. However, these practices are far from

localized in the Global South only (Pierre et al., 2019).

26. Apart from natural pecking orders like prey/predator relationships.

27. By doing so, scholars and scientists believed they could fully decode the workings of the natural world (Kosinski, 2020).

28. Many scientists argue that the human induced changes to Earth’s geological systems are enough to

consider it a geological epoch (Demos, 2017).

29. The Global South is a term used to describe less industrialized nations in the southern

hemisphere, which are often times the victims of global capitalism.

30. Donna Haraway describes this event as the Plantation-o-cene, or Plantationocene (Haraway, 2016).

The ANTHROPOCAPITALOCENE

Today, a huge portion of Earth’s natural landscapes has been turned into a resource[7]. Humans manage

three quarters of all land outside the ice sheets, and almost half of our planet’s habitable land is used

for agriculture (Globaïa, 2009). The claiming, clearing, and cultivation of these lands in the pursuit

of profit, have created enormous devastation on an unimaginable scale, both for the lifeforms involved,

and the ecosystems that encompass and sustain them. The catastrophic impacts are almost countless: we’re

currently experiencing rising temperatures, melting ice caps, thawing permafrost, and ocean

acidification (Edwards, Graulund & Höglund, 2022). It’s also

“extraordinary burdens of toxic chemistry, mining, nuclear pollution, depletion of lakes and rivers

under and above ground, ecosystem simplification, vast genocides of people and other critters,[…]

in systemically linked patterns that threaten major system collapse after major system collapse

after major system collapse”

(Haraway, 2016, p. 100).

Not only have forces of human existence altered Earth’s cycles (Globaïa, 2009), but also overwhelmed

all other biological, geological, and meteorological forms and forces and became the determinate form of

our planetary existence. Many would like to label this event the controversial Anthropocene–or the age

of the New Human (Povinelli, 2017).

This terminology, though initially seeming fitting for the circumstance, has

since been a matter of heated debate among scientists & researchers (Zhong, 2024), as it pins blame on all

humans which is neither fair nor true–and frankly, kind of a cop-out for the true powers at hand.

Writer TJ Demos, in his book Against the Anthropocene, dismisses this term as asymmetric and

inherently wrong (Demos, 2017).

It’s imperative to mention that the most dominant force in all this destruction have without a doubt

been the forces of corporate industry, which not-so-coincidentally have most to lose if we’d head

for a more environmentally friendly route of planetary existence. Here, Demos points towards indigenous

practices and states that the corporate facilitators of planetary destruction shift blame towards

the individual. In fact, the corporate and financial elites and growth-obsessed leaders of the

petrocapitalist industry do everything in their power to keep humans on the same path, by using

their financial and media resources to “manipulate governments through corporate lobbying remove sustainable energy options from even entering the discussion, fund climate change deniers,

and advocate for continued large-scale and extreme fossil fuel extraction” (Demos, 2017, p. 29).

Because of this, many prefer the more appropriate name Capitalocene; as it exposes the culprit in its name and highlights the “economic determination of our geological

present” (Demos, 2017, p. 55). Many more terms have been used to describe this period, which all say too much

and too little at the same time. I propose a sort of amalgamation of the two we’ve already mentioned:

“the AnthropoCapitalocene”, a handy term which simultaneously opens up, and names and blames

in all the right places.

31. Coined by biologist Eugene Stoermer and popularized by chemist Paul Crutzen in 2000. Anthropo-,

a prefix meaning human, humanoid, or human-like, and -cene as being new (Demos, 2017).

32. “Total oil and gas lobby spending in 2015 in the United States was an astounding $129,876,004,

which breaks down into the figure of $355,825 per day, a financial driver that makes sure that renewable

energy is kept off the table and safely away from consumers” (Demos, 2017).

33. Initiated by author and ecologist Andreas Malm and widely used by scholars, scientists &

eco-researchers like Donna Haraway, Jason Moore, T. J. Demos, and others in recent years.

EARTH, REVISED & UNRAVELLED

Nature’s revised definition as a machine quickly spread to other levels of Western human existence,

and while the landscape became a resource, humans got commodified as workers. The Industrial

Revolution

produced many mechanisms and phenomena that sped up the machine’s production while lowering costs,

such as factories, assembly lines, and mass production. For

the first time, factories rendered humans capable of existing independently outside of their farmlands (and

comparable ecosystems). Even though the work was both hazardous and incredibly monotonous for the workers, it

generated immense profits for the factory owners, who prioritized production and profit over all

else.

Their management of the workers’ labour was rooted in efficiency, utility and optimization; and both introduced & solidified the human-work relationship we experience today. Not to mention

the incredibly destructive impact the industrialization had on Earth’s systems, which many tie to the

beginning of the AnthropoCapitalocene. While mass production of goods made them more accessible and

affordable, they became standardized and subsequently simplified[8] (Rafferty, 2017). In many ways, the

utilization and standardization of the West stripped the landscape of its superficial layers and

revealed a sterile, homogenous terrain, critically lacking in diversity, in all senses of the word.

Naturally, the accelerating destruction and alteration, automattion, standardization, monetization,

rationalization & utilization of Earth in the last 300 or so years, has led to many cycles of

opposition. It’s also been the root cause behind an ongoing conversation in art and design fields. A

hundred years into the effects of the Industrial Revolution, we saw the Arts & Crafts movement in

Great Britain (and North America); a direct response to the industrialization of Europe, which advocated

for a return to nature

and traditional craftsmanship in rejection to mass production. Shortly after, it was Art Nouveau in Belgium[9] and

France, Jugendstil in Germany, Sezessionstil in Austria, Stile Floreale/Liberty in Italy, and many other representations.

In one way or another, these movements promoted nature and the natural form, which they used for inspiration, and as a guide or grid system in their various creations. Their vision was

translated into ornamental forms across medias, which helped the jagged, organic line we love and

adore,

flow seamlessly from nature into built society, and bridge the gap between the organic- & strikingly

mechanical landscapes. Modernism emerged as a reaction against these movements, and sought to unify the landscape through subtraction and

simplification. The rugged, flowing line flattened out, and the grid became rigid, straight and

synthetic. Natural references were exiled under utilitarian Modernism, and ornaments and other

decorative parts were served cease-and-desist

orders (Pierre et al., 2019). And while wildflowers got mowed from monoculture landscapes & species

found themselves in a mass extinction (Morton, 2021), it’s almost like they were never there.

“The ornamental reminds us that life is more whole than the divisions of leisure

and work, useful and decoration, business and pleasure, or individual and communal, as it resists the reduction of life and value to what is utilizable […]

It’s an elusive antithesis to singularity, objectivity, effectiveness”

(Ehde & Rafstedt, 2019).

Of course, this is only a small fraction of the vast discourse on the past, present and futures of

terrestrial beings and systems in the AnthroCapitalocene, and many have taken far more radical

measures in promoting nature and advocating for environmental action. In recent years, we’ve witnessed

large-scale climate activism, such as the global Fridays for Future school strikes initiated by

Greta Thunberg (Fridays for Future, n.d.); Indigenous-led efforts to protect land and water in the Amazon

rainforest

(Amazon Frontlines, 2019); Extinction Rebellion’s fierce protests against fossil fuel projects in

Germany and the Netherlands (Extinction Rebellion,

n.d.), and numerous legal cases recognizing the rights of nature (Freedman, 2024).

34. The Industrial Revolution originated in Great Britain and lasted from 1760 to around 1830.

35. Industrialist Henry Ford invented the moving assembly line, and revolutionized factory

production forever. However, the line was seen as an insult to skilled craftsmen, and “another example of the

overwhelming patriarchal control a company could have over its workers in the age of mass

production” (Eschner, 2016).

36. Engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor was a pioneer in production-optimization-strategies and

developed Taylorism, a popular method of industrial management designed to increase efficiency and

productivity, where workflows and work processes are examined and optimized to reduce costs and increase quality

(Munich Business School, n.d.).

37. See: William Morris’ art and fiction writing, which envisions a world where humans are

integrated with all of nature.

38. A grid system is a visual guide that is used to organize and align elements within a design.

39. And as a reaction to the World Wars and accelerating industrialization.

40. Modernist architect Adolf Loos famously exiled ornaments and decoration with his manifesto

Ornament and Crime in 1908, whose radical ideas significantly influenced the development of modernist visual

landscapes.

41. In 2019 in Ecuador, the Waorani people of Pastaza won a historic ruling in Ecuadorian court,

protecting half a million acres of their territory in the Amazon rainforest from being earmarked for

oil drilling (Amazon Frontlines, 2019).

42. Extinction Rebellion says this on their website: “This is an Emergency. Our climate is changing

faster than we predicted, and those in power have failed to act. Extinction Rebellion is demanding

fair and transparent change, to ensure the future of all life on Earth” (Extinction Rebellion, n.d.).

US as EVERYTHING

STORYTELLING as WORLD-BUILDING

Little by little, the conversations we have about the world end up amounting to the world itself. We

create it by speaking it into existence, and through it, decide who is and is not part of the story.

Author Ursula K. Le Guin famously describes this story-making and history-making

as an accumulative process of gathering stories in bags–which, throughout human history, has proved

preferential to hu-man centric, western-centric, heroic and

action-packed narratives, over accounts of delicate care and

companionship, motherhood and many layered complexities of Earthly existence (Le Guin, 1986).

“Where is that wonderful, big, long, hard thing, a bone, I believe, that the

Ape Man first bashed somebody in the movie and then, grunting with ecstasy

at having achieved the first proper murder, flung up into the sky, and whirling

there it became a space ship thrusting its way into the cosmos to fertilize it

and produce at the end of the movie a lovely fetus, a boy of course,

drifting around the Milky Way without (oddly enough)

any womb, any matrix at all?”

(ibid., p. 167).

Other stories become just other stories when they get reduced to supporting acts for the hero.

Ironically, the hero in our Anthropocene-story is not humanity and not even hu-man, but a tiny

sliver of egotistically profit-driven hu-men or entities. And the victor writes the history and all that. We

must be generous in what stories we gather in our bags; what kinds of stories and of whom and from which

perspectives.

“It matters what stories make worlds & what worlds make stories”

(Haraway, 2016, p. 35).

One way of telling the story of the AnthropoCapitalocene would be of a heroic battle between hu-man

and

nature, where man won the war and harnessed the powers of nature to use in his divine quest for

redemption. It’s also a story of an indigenous person whose home got swallowed by petro-chemical

infrastructures, displacing her whole community and permanently destroying her health

(Demos, 2017). Earthlings in some subtropical grasslands might know it as the event where everything

they thought they knew about their section of the world got turned on its head and collapsed

(Rosane, 2020). For more than two million species it’s probably nothing short of Armageddon, but since

they’re now extinct they can’t really share their stories (Odenthal & Suner, n.d.). Of course, there’s too

many stories to possibly condense into a singular narrative, and that’s exactly the point. We have to

allow more stories and more points of views to enter the discussion, not only human but, and especially,

all terrestrial species. And we must reject the hu-man

exceptionalist-,

anthropomorphic and anthropocentric point of

view, if we want to keep on telling the story. “A common livable world must be composed, bit by bit,

or not at all” (Latour, 2010, p. 473).

Like in Dr. Seuss’ fable, we must use our agency to give voice to the other and speak worlds beyond

ours into collective existence. Seuss’ story–though fictional and totally anthropomorphic–represents

a type of alternative storytelling, which is another

thing we absolutely must do. We must tell more stories; fictional, autobiographical, scientific, pretend and

make-believe, critical and speculative, mediocre and fantastical stories; through writing, painting, film- and

music-making, note-taking, speaking into existence and scribbling on a wall; stories of what was and

will be, what could be, what shouldn’t be, what is and is not. This is how we create the world, and

also how we change it. Regardless of their nature, regular-human stories are still

terrestrial-being-stories, world-making and world-changing stories.

43. Or his-story-making?

44. I propose a distinction between human and hu-man: where the former refers to any individual of

the human species, while the latter represents a Western, male-centric and idealized reproduction of a

hu-man individual.

45. “The situation of environmental injustice is similar elsewhere: like the Athabasca Chipewyan,

minority and low income communities living on the edges of the massive petro-chemical infrastructure

in Houston suffer greatly elevated risks of contracting leukemia and cancers owing to exposure to oil

industry pollution” (Demos, 2017, pp. 28-29).

46. Anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour calls these stories Earth stories, Gaïa stories or

geostories: where all formerly passive agents of nature become active, as part of the story

(Haraway, 2016).

47. A phenomena is anthropomorphic when it has a human form or human attributes.

48. Anthropocentric means human-centric and refers to the view of humans being the central, most

important element of existence.

49. “Alternative Narratives encompass a spectrum of voices, experiences, and viewpoints that diverge

from dominant narratives prevalent in society” (The Oxford Review, n.d.).

Semiotics play a huge role in storytelling. Either I did something, or you did something, or maybe

they did it, or maybe we did. Like with the bag and the bone and with othering others, when talking about

us, we exclude them from the story. In the context of this chapter, or chapter title, us could be you &

me, or

all of humankind, or a section of humanity in a specific circumstance, or more than humanity.

Evolutionary biologist W.D. Hamilton found that the closer we feel towards another member of any species, the more willing we

are to protect and care for them (Hamilton, 1964). I can’t help but wonder

what would happen if we stretched the notion of us so far that it’d encompass all lifeforms with and outside of our

own. In theory, it could generate a lot more empathy, a crucial ingredient for moving past the

AnthropoCapitalocene.

“When you were dying, you knew I’d fight for you

if I thought I was dying too”

(Shore, 2007)

For Donna Haraway, this is how we “make kin” with one another. By embracing the relations between us

terrestrial species and bringing other lifeforms into our notion of us. Etymologically speaking, kin

stands for relations with–often as family or chosen family. So, when we refer to our family of human

species, we become human-kin, or humankind. Haraway suggests that when referring to our extended

family members, we can call them Earth-kin/Earthkin, since all of us Earthlings are kin in the deepest

sense of the word

And by considering the multiplicity of us entangled Earthlings, we engage in tentacular thinking

about and with the world. The word for world being, in this

context, the fluid and flourishing, interconnected, non-binary and non-linear, intricately yet indeterminably woven web

of life on Earth. There are no shortcuts when it comes to world-making, the only way is through. There

are many steps required for moving past the AnthropoCapitalocene, too many for a subsection of a

singular species or entity, and emerging into the other side requires making kin in the current world.

Collectively, we can evoke an entangled and tentacular world, the Cthulucene, perhaps (Haraway, 2016).

“It sometimes seems that the story is approaching its end. Lest there be no

more telling of stories at all […] I think we’d better start telling another

one, which maybe people can go on with when the old one’s finished. Maybe.

The trouble is, we’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story, and

so we may get finished along with it. Hence it is with a certain feeling of

urgency that I seek the nature, subject, words of the other story,

the untold one, the life story”

(Le Guin, 1986, p. 169).

50. As the reader and the writer.

51. As humans.

52. And perceived closeness surpasses genealogical relations.

53. Dr. Cameron to Dr. Foreman in tv series House (S4ep06).

54. “All critters share a common “flesh,” laterally, semiotically, and genealogically” (Haraway,

2016, 103).

55. “Tentacularity is about the myriad of entangled ways of being.” (Haraway, 2016, 32). Her

“tentacular-ity” is inspired by tentacled creatures like octopuses and spiders, which weave

intricate, networked relationships rather than following linear, human-centric modes of thinking. Tentacular

thinking is the opposite of rigid, individualistic, and anthropocentric worldviews. At it’s core,

tentacular thinking is non-anthropocentic ecological thinking.

56. Not to be confused with HP Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu”, although linked through the notion of

evoking something tentacular and beyond human control. Haraway’s “Cthulu” is derived from

“chthonic”, meaning “of the earth” or “underworld,” referring to deep, ancient, and earthly forces (Haraway,

2016).

EPILOGUE

At the end of the hero-story in the action-movie, the daring protagonist blows up the building with

the bad guys in it and flees the scorched-Earth remnants of the planet in his Ark or spaceship, to

someplace where the grass is greener, with his dear ones aboard, and to hell with all that’s left behind, if

it doesn’t contribute to his story. But his imagined elsewhere is only a mirage, and no one told him

that escapist fantasies make futile exit strategies, and that he’s rendered useless without Earth’s soil

and place within its cyclical life-sustaining systems. And so, as it tends to, the life-story carries on

in his absence; weaving tales about tube worms in hydrothermal vents on ocean floors, spiders on

mountains, and natures breaking through cement landscapes. He should’ve known that every end of a successful

hero’s journey requires a return to origins, reconciliation and mourning, reparation and renewal. The

continuation of his story depends on weaving it in with and acknowledging it as part of the original

story, the life-story, the entangled multi-species story of life on his home planet. Only from this

recognition can he move forward, not as a glorious victor but a humble participant in a shared,

intertwined world. The grass on his side is already green enough, he just needs to water it ⚘

COLOPHON

Heartfelt thanks to my dear parents and my siblings, to Prof. Dr. Füsun Türetken, Thomas Buxo, François Girard-Meunier, Patrycja Fixl, Joana Soares de Albergaria Ambar Sobral,

Balázs Milánik, Jim Olijkan & Dr. Alessandro Ianniello: thank you for your profound insight and endless inspiration, guidance, care and companionship during the thesis-writing and website-making.

Fonts in use: Instrument Serif, Sentient, Courier, Baskerville & Edwardian Script ITC.

Royal Academy of Arts the Hague, Graphic Design department.

B.A. Thesis 2025

Guided by Prof. Dr. Füsun Türetken

Written by Dagný Rósa Vignisdóttir