In 2023, one could easily state that we live in upsetting times and are constantly dealing with the consequences and hardships of our busy existence. From ecological disasters to manmade atrocities, it seems that everything we are surrounded with has an expiring date, and we are constantly faced with various levels of degradation.

Being a process, decay has a temporality, a pace or a tempo, and a spatiality, a mode of occupying and evolving in a space. (Ghassan Hager, pp.13) Things decay in quite diverse ways, and it would be absurd to assume otherwise or to ignore the particulars behind it. But as decay seems to float between abstract and objective implications, it is only normal to wonder; what do we mean when we talk about being in a period of How can we measure or recognise it as such? Or in a more tangible connotation, what are we talking about when we refer to bodily, material, or infrastructural decay? Such questions would be explored and argued within these pages, as it requires some reflection, given that most people of the world take it for granted that decay is the normal order of things. (ibid)

As previously mentioned, there are several stages in which decay can be found. But we often understand decay from an organic point of view, which includes two processes of importance: Endo-decay, where decomposition comes from the inside-out and Exo-decay, where it is caused by external environmental forces. This differentiation between Endo-decay and Exo-decay is hardly ever neat, and the two processes can often be entangled in the making and unmaking of social processes. (ibid) Such statement opens a window to consider the wider aspects and relations that it carries, from a material and infrastructural process of degradation to a condition for social and moral decline.

Hence, from a material and infrastructural point of view, it would be smart to also consider the tempo and the agency in which things decay. As mentioned by Ghassan Hager in his book Decay: “Decomposition and disintegration are no longer happening imperceptibly, where, and how they should.” This raises questions about the temporality, functionality, and the development of the environments in which decay can thrive. As well as the speed at which we create, relate, and consume matter. We will also dive into the importance of maintenance work and human agency in the face of decay. Touching upon notions of preservation through archaeology and technology. Furthermore, if we focus on the social and moral aspects of decay, we can pinpoint war as one of the major contributors of such demeaning. As it often involves the use of violence and aggression, the destruction of infrastructure and property – precisely targeted at the destruction of cultural heritage – moral decay, and ultimately the loss of lives. These things can all contribute to a decline in values and standards and can lead to a breakdown of social and political order. Moreover, they contribute to the loss of collective memory and to the damage or partial loss of culture.

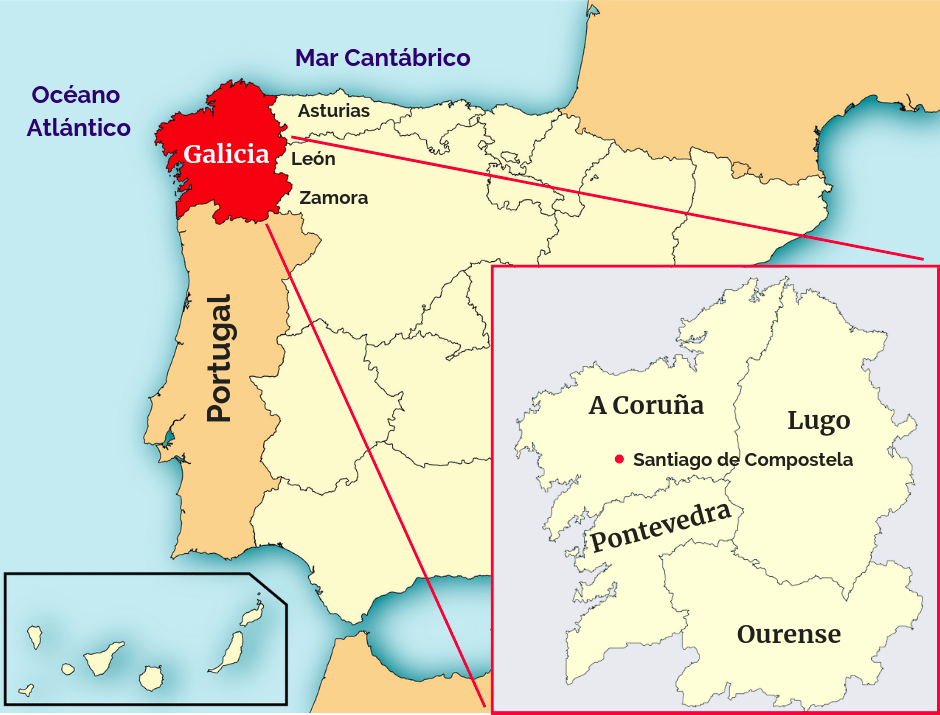

A clear example of such collective loss can be seen in culturally diverse countries that underwent large war periods, such as Spain. More specifically in Galiza, where the impact of the 40-year dictatorship under Franco’s ruling was, and still is of importance. It contributed to the erasure and damage of the culture and language of the Galizan territory, something that still has an enormous repercussion in our contemporary society. Such is the repercussion today that, three generations later, Galizans like me, are barely acquaintance with the language nor the story of their own region. Therefore, I write this text out of the urgency for the restoration of Galiza’s collective memory, and the desire for the survival of its language. On the other hand, I also write from the perspective of someone that holds the tools and responsibility for visual communication and can thus, play a role in the mitigation of such decay.

In order to gain a more nuanced and understanding idea of decay, it is important to comprehend it as a multiscalar and multifaceted process. It is not always simple or straightforward, and the several factors that contribute to decay can interact and influence each other in complex ways. Recognizing that decay can have both negative and positive aspects can help us approach it more objectively and to find ways to address and mitigate its negative impacts while also taking advantage of its potential for growth and renewal.

I realized there was a part of the recent history of my country (Spain) more specifically of Galiza, that I had not been told at home, at school, nor on the street. It is something that is not talked about enough. As if not mentioning it would mean it never happened. With “out of tempo” I aim to speak of silence and the untold stories that emerge from oppression. This would be a walk through the forgotten, the decayed, the effects of purposely silencing parts of a culture.

Of the negligence towards the past, and thus, towards the future.

ON GALIZA'S DECAY

As previously mentioned, social decay can be understood and explored within the context of war-torn territories. Using Galiza as a case study, I will illustrate the ways in which the oppression experienced during the Civil War contributed to the erosion of a language, and how this had a direct impact on the preservation of the Galizan culture.

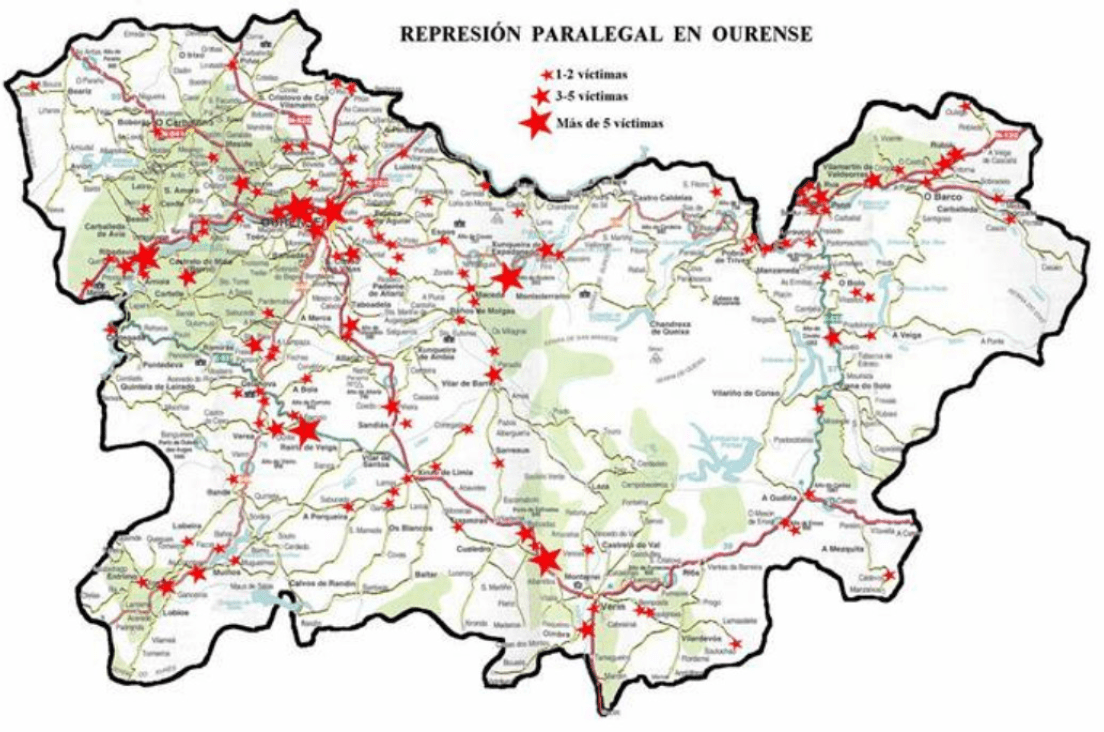

Starting in the summer of 1936 with the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, there were thousands of acts of oppression between the Republicans and the Nationalists. During the three years of the war, it is estimated that the Francoists murdered approximately 5000 political dissidents, while silencing most of the living witnesses and destroying most of the written testimonies. (Thompson, John. 2014) Anyone with liberal ideas contrary to the national movement – even in places where there had never been a war front – like Galiza, were faced with executions. It is most likely because of this factor, that Galiza has remained until recently relatively invisible within the Spanish Civil War.

In the case of Galiza, the region immediately fell under Francisco Franco’s totalitarian regime, and even though the fascist repression was extremely disproportionate in comparison to other areas of Spain, not much armed opposition was encountered. This brutal repression is important to understand the politics of forgetting in present Galiza. Both migrations and centralism within the territory created an image of a colonial subject under the regime that was rapidly assimilated by Galizans. (Gonzalez-Ruibal, Alfredo. 2005)

And so it begins,

a blunt sound,

a crack.

A downfall.

A destruction from within… then silence.

They say it’s about the way I move the mouth, and the noise produced while doing so. Have you ever noticed? When I speak of the mouth, I am not necessarily talking about mine, but that one of others. I am performed through and by it. The mouth of one is the mouth of many, and eventually, of me. And so, like the air, I am a force, a constant that goes in and out of the mouth, back and forth the mouth.

There is something of the air in me. I am talking about the type of air that enters the bodies of those who hold me. It strengthens me, and as their lungs expand, I simul-taneously move upwards. Softly, I start dancing within their throats, rejoicing on their wet tongues as I wait for the sudden push. For the air that frees me from their bodies. Through this push, I can be as soft as a fallen leaf or loud as tree branches crashing during a storm. Gentle or rude, I can also be an echo, a constant voice. Like the one you choose to keep inside your head, the one you’re often too afraid to speak of. Through the spaces I inhabit, I can move so gracefully that I’ve been told I resemble a song. That I have a tone, a melody that’s inherently mine, as well as of those who hold me in their mouths. The thing about the air is that it helps me travel through the multitudes, as I go from mouth to mouth and ear to ear, I go from time to time.

And so, for a while, I believed I was eternal.

In order to be able to understand the oppression of the Galizan territory from a possible colonial perspective, it's important to note that Spain treated Galiza as a marginal periphery deserving limited space in the configuration of the Spanish kingdom and identity, and therefore Galiza could be considered and analyzed in comparison with other countries under colonial regimes.

(Rei-Doval, Gabriel 2016) While it was not a colony in the traditional sense – as it was not a territory controlled by a foreign power – it was, however, treated as one by the regime.

As mentioned by professor Xosé Manuel Beiras in his book Galiza’s economic backwardness: “Galiza had historically been and still is an “internal colony”. The continuous struggle for power, recognition and preservation of its culture and identity can be seen as a way for its people to assert their identity and challenge the dominance of the dominant group. Franco’s fascist dictatorship conveyed not only a political but also a linguistic and cultural repression. Specific economic and cultural factors –– such as a particular intense urbanization process and the imposition of Spanish as the dominant language in school –– contributed to the shift in informal usage of the Galizan language.

ON GALEGO AS RESISTANCE

Galego is a minority language spoken in the northwestern area of Spain, it is amongst the myriad of minority languages in Europe, holding a distinguished position as one of only three official languages of the Spanish region.

(Rei-Doval, Gabriel 2016) Both Galizan and Spanish belong to the Romance language family, sharing a significant amount of vocabulary due to their common roots in Latin, but differ in grammatical features, sounds and phonetic rules. The proximity between Spanish and Galego has historically facilitated communication, but al-so language shift from Galego towards Spanish.

(Rei-Doval, Gabriel 2016)

It was a summer morning like any other.

One of those mornings when Cee gets up rather early to enjoy some solitude by the dock and appreciate the sunrise on her way to the bakery. Because as we often say: the best bread of the day is the one baked under the first rays of light. As she started eating it, I began to dance around her mouth, mumbling indescribably. And as I’d later realize, that was a sign of pleasure.As Cee was getting back into town, she started sensing a rather odd atmosphere. The space around us started changing, it was getting impregnated by something new. Suddenly, we could sense how trees and buildings vibrated and echoed differently, the soil and the air felt stiffer than ever, and being around people was rather strange. I guess what struck me the most was the sudden silence. Have you ever been in a place, an environment that’s often blooming and charged with life, that suddenly becomes quiet? It can be quite disturbing. It is almost as if it lost its soul, its essence. As she continued walking through this silenced town, she bumped into some acquaintances and I greeted them as usual, but this time, weirdly enough, I wasn’t reciprocated. I felt invisible in their eyes – in her mouth – as if I weren’t there, as if they could no longer see me. This triggered something in me I have never felt before. Although I have been told by many it’s called fear. The day went by, and I tried to forget about the incident. Hour after hour, I kept wondering whether this was a one-time kind of thing. And so, I tried to see myself in the mouths, in the bodies of others without success. The next morning, as I waited inside for her to wake up, I felt hopeful for things to be back to normal, to, in a way, understand that yesterday was just all a misunderstanding.

The issue of language endangerment has long been discussed in Galiza, where a clear competition between a dominant (Castilian-Spanish) and non-dominant (Galego) language can be found. The dominant versus non-dominant struggle could be analyzed through the lens of , in the sense that it can help to explain how dominant social groups maintain and reproduce their power through the control and manipulation of cultural institutions, values and ideas.

In the context of Galiza, this could be seen in the ways in which the Spanish state, during Franco’s regime, used its control over education, media and cultural institutions to promote the use of Spanish and marginalize the use of Galego. Furthermore, as Galiza lacked a middle class speaking the language, the use of Spanish was directly associated with prestige. The school system, the media and the economy related to the tertiary sector (industry, services etc) have historically functioned on the language of the dominant nation-state. As a result, this has helped to shape language behav-ior and practices, promoting the usage of Spanish in these settings. (Ibid)

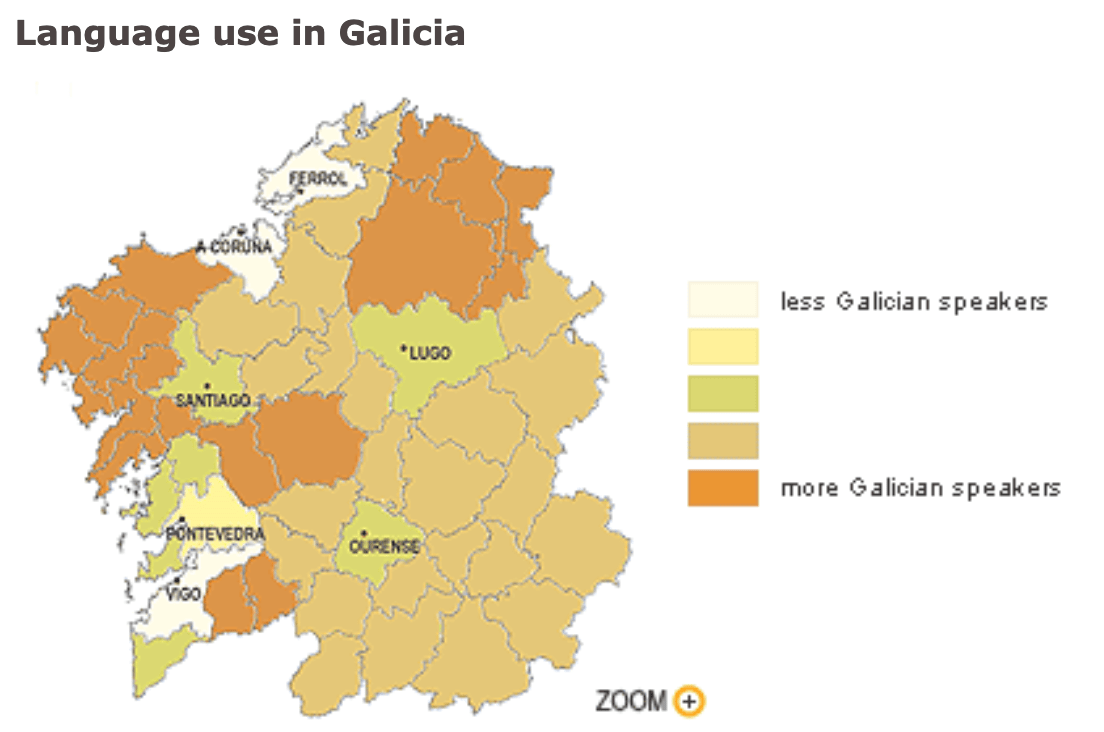

Cartography of Galego's use in Galiza[1]

Locating the context[2]

However, it is clear that in regard to the Galizan case, is not just a matter of linguistic or cul-tural difference, but also a struggle between dominant and subaltern groups for power. The struggle for recognition and preservation of the Galizan language can be seen as a way to as-sert its identity and to challenge the dominant group. There are no doubts that the destruction during, and oppression after the Spanish Civil War reversed decades of Galizan cultural progress.

(Language Conflict Encyclopedia) But the story of Galego is one of resistance, as it has been fighting for its position as an official language since the Middle Ages. Back then, the idea of the Galizan language being at risk, was more of a potential threat rather than a practical concern. But with the development of urban and academic areas and the effects of the Civil War, came the fear of such loss. Revitalization efforts only started in the 19th century as part of the pro-cess that Galizan historiography has called Rexurdimento or revival of its language and culture.

(Rei-Doval, Gabriel 2016)

As Cee went on with her day,

I started experiencing the same odd feeling but this time, the city had changed. I was no longer able to be outside peacefully – seeing Cee enjoying the solitude of the dock felt like an old myth and for some reason, I was stuck in her mouth.

Time stood still as troops were marching into the city; for a little while, before it all erupted, people were standing quietly, out of fear I believe. It was somehow a similar fear as the one I felt yesterday, yet, today, I was experiencing it from a different position. As if this type of fear didn’t apply to me. As if in a way, I wasn’t going to be touched by it.

Within a split second, multitudes were running, screaming... houses were broken into, and businesses were burnt down, it was the most accurate definition of chaos I’ve ever seen. Still, I couldn’t understand them, their screams, their cries for help... It felt as if nothing was actually intended for me, but somehow, I happened to be in between of it all. Suddenly, it all turned quiet, as if I were inside a bubble, I was floating, experiencing things from the inside out, unable to fully grasp it, unable to be seen, nor hear.

These resistance efforts – as a response to the oppressive , were done by minority groups formed (mostly) by intellectuals. Constituting a pivotal moment in the preservation and promotion of Galizan culture by making the lan-guage visible within the spoken and written scope. They performed acts that emerged with the goal of overcoming , such acts consisted – among others – on the making of publishing houses and editorial work in Galego, like “Galaxy Editorial” and the magazine “Grial“ for example.

(Editorial Galaxia)

Example of Grial magazine 1985[3]

Example of Grial magazine[4]

These acts promoted the use of Galego as a cultural heritage worthy of preservation, as ei-ther a unique manifestation of an original culture or as the most recognizable symbol of a differentiated collective identity. However, as these acts of resistance were considered illegal during the regime, they were mostly performed from abroad – as many Galizan citizens were forced to exile due to political persecutions and in search for better economic opportunities.

As I kept moving,

I was suddenly looked at, right into my soul. From across the square, I could hear a voice trying to communicate with me, a voice although it seemed familiar, I could only understand it partially. For a split second, I felt as if that voice was mine, just a little different.I started sensing this voice was new here, but equally old among them all, it was impregnating it all rather quickly, almost leaving no space for my own. As soon as voice noticed me, it smiled as if we were old pals, as if we shared a common ground, it was a smile that made my teeth grind and my body shiver. I tried to make contact, I screamed and shouted, hoping for an explanation for all this outer silence. But voice kept laughing at my efforts. It had a laugh so twisted that got wrapped within my skin, making me feel dizzy and asleep. Once I woke up, I was still inside the bubble, but this time, everything around me had turned into shadows, I was alone. I could almost see things, but nobody could see me. I couldn’t speak, and although I could hear things happening around me, I couldn’t understand them. It was like I had woken up in a completely different reality.

Such exile contributed to the growth of Galizan in Argentina, Mexico and Uruguay, from where a big part of the political and cultural resistance was performed. Something that played a direct role in the future decay of the language within private settings in Galiza and as Gabriel Rei-Doval

(2016) points out, it is fair to say that the percent-age of monolingual Galizan speakers has decreased over time, in part, favored by the easy transition from Spanish and also by the fact that the urbanization process in Galiza has led to the disappearance of the cultural references and habits that had favored the continued use of Galego in rural areas over the centuries.

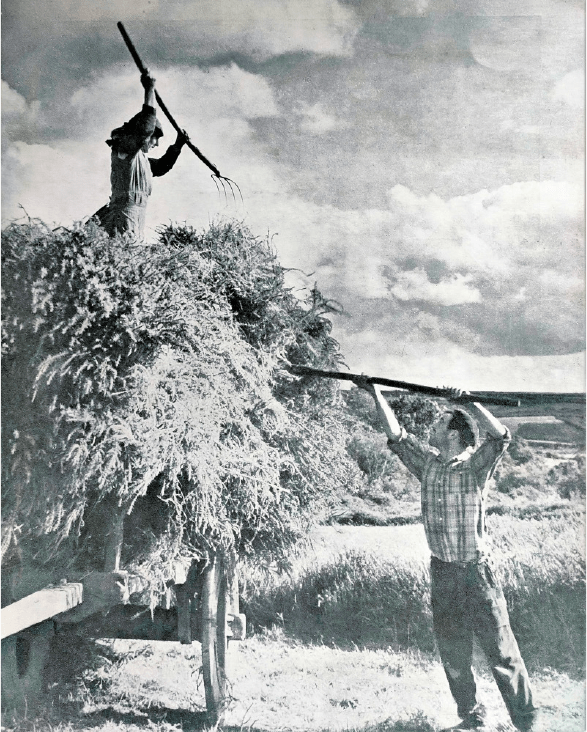

As Castilian’s link to prestige forced the use of Galego to rural areas, these were – and still are – responsible for the survival of the language. People performing agricultural practices for example, own their particular vocabulary and expressions, which are passed down through generations by oral story telling. The same way, Galizan rich folklore is only per-formed in Galego and its traditions are again, passed down orally from generation to generation – helping to keep the language alive. Religious practices have also been passed on in this language. With specific vocabulary and expressions becoming deeply rooted in the language within these areas, we can recognize the language as a carrier and container of habits and knowledge. Thus, shutting it down or hindering an entire population from speaking it, creates serious repercussions on the culture.

Img 1. From Visual essay on kinship practices[5]

Img 2. From Visual essay on kinship practices[6]

Img 3. From Visual essay on kinship practices[7]

Img 4. From Visual essay on kinship practices[8]

These activities represent the citizens’ desire for the survival of the language and showcase a lack of commitment from the government to keep it alive within bigger sectors. In 1983 a Law for was put in place to form the basis of in Galiza, aiming for a “balanced bilingualism” in society. Still, the government continuously maintains a strong centralist approach which is evident from their pro-Castilian discourses.

(Nandi, Anik. 2017)

And if we consider latest statement: “it should be the family, and not the education system, which is responsible for intergenerational transmission of Galego” we can clearly understand that the government, quickly allocates the responsibility for the language’s survival and consequently loss, to the individuals, as a justification for the incessant language shift to Castilian. (Nandi, Anik. 2017)

I can’t tell you much about the shadows.

Besides the excruciating silence of it all, nothing really happened there. Every now and then I was able to escape. Sometimes I’d walk for what felt like an eternity, and eventually, I’d stumble upon people that tried to keep me alive. I found places where they kept communicating with me and for a split second, I felt free, I was able to move between them all, to dance with their bodies, their mouths… These places were comforting and warm, they almost felt like home, except for the constant fear. It was linked to my presence – sometimes instead of the mouth, they had to use their arms and hands to perform me.

The language is clearly used as a tool to meddle with cul-tural heritage and exemplifies how the idea of nation states lead to the promotion of homogenous makeup, based on ethnicity, language and religious practices, eventually perpetuating a narrow and exclusionary conception of nationalism. However, Galiza presents a unique case in which the decline of its language serves not only as the portray of a loss, but also as a call to action for its preservation.

And although we should respect the execution of individual freedom of language selection in a multi or bilingual society, the government should facilitate Galego’s progress and accessibility, and in fact empower its use. Nourishing and protecting Spain’s cultural diversity should be of utmost importance to ensure a thriving and inclusive society.

So, they kept me hidden,

and as the idea of me was simply fading away, I stayed, I waited and experienced everything from the inside. From the shadows, I saw everyone passing by, continuing with their lives, using voice instead of me, as if I had never existed.

I have been told by some,

that I spent 40 years in the shadows.

The language is clearly used as a tool to meddle with cul-tural heritage and exemplifies how the idea of nation states lead to the promotion of homogenous makeup, based on ethnicity, language and religious practices, eventually perpetuating a narrow and exclusionary conception of nationalism.

However, Galiza presents a unique case in which the decline of its language serves not only as the portray of a loss, but also as a call to action for its preservation. And although we should respect the execution of individual freedom of language selection in a multi or bilingual society, the government should facilitate Galego’s progress and accessibility, and in fact empower its use. Nourishing and protecting Spain’s cultural diversity should be of utmost importance to ensure a thriving and inclusive society.

“We do not own the rock. The rock is itself its own history. It is alive and one must redefine what being alive means… because we are just thinking within the scope of our own limited realities. Do we really believe that some-thing is alive when it acts – from breathing, photosynthesis or walking – or can we see life in a broader scope, as change-time for example? Erosion and mineral residue… are they not processes of “aliveness”?You shall respect the rock as it is older than you. And you, honestly, should know better.”

- Odete in The elder femme and other stone writings

ON PERPETUATION

After the Spanish Civil War in 1977, in an effort to find peace and allow a fresh start for a democracy, the Spanish government put in place an amnesty law called the As an attempt to move on from the war, and focus on the future of Spain, the government committed itself to “disremembering”. By doing so, it failed to hold accountable those who contributed to the many atrocities committed under the name of the regime. Such law plays a crucial role in the perpetuation of power structures and hinders the ability to fully examine, understand and learn from the past – potentially making it difficult to ensure that similar atrocities will never occur in the future. The work of examining any contested history of a na-tion, are at the core of remembrance and memory work.

"Between the steep angles

and the old looking stone houses, they got lost several times. Not because they didn’t know where to go, but because the way they walk me is, after all, not premeditated by them. As time stands still, I show them the way between my insides and outsides.

The perfectly painted tiles, the carvings and the ornaments on the stones, speak of the beauty to be seen in this land. And by all the beauty that’s visible, for a second, they forget about what might be hidden. What is underneath, what remains... stays quiet, waiting to be found.

It is like a game. And let’s admit it, I do like playing hide and seek."

I am constantly surrounded by people yet; I always find myself in solitude. I often wonder what Vee thinks as she walks through me. Sometimes rushed, others slow, trying to take it all in as if it were her first time here. She goes through me a total of 6 times a day: the first time of the day is always at around 8 am – this, however, only applies for four of the seven days of the week. At around that time, she is usually very sleepy and moving slowly and clumsy while trying to rush her way toward the coffee shop. Then, I don’t see her again for another four hours and I must kill my time with others. She comes back to me at around midday, and we spend an hour together. She eats her lunch slowly while reading, and by the tremor of her hands, I can assume she’s on her third or fourth coffee of the day.

This is, by far, my favorite time of the day. Not only because it’s the longest we spend together, but because she talks to me. I mean, I know, she is not talking to me, as she isn’t aware I can actually listen. But I like to think that deep down, she does.

The endless difficulties in the exhumation of mass graves, places of repression, and the continued use of war monuments in public spaces are just some examples of its repercus-sions. This law should not only be understood as a missed opportunity to promote accounta-bility and reconciliation, but as a fertile ground for the creation of false – and populist– narra-tives. The recent discovery and excavation of sites of violence – like the Island of San Simón or The Tui Avenue, that were long forgotten or suppressed, bring to light the evidence of such narratives, but it also raises critical questions such as: Is it possible to collectively address and re-work these sites of violence? What is the current significance and role of monuments that commemorate such events? and how does the maintenance of lack thereof of such sites affect our collective memory?

“It would be useless to turn one’s back on the past in order simply to concentrate on the future. It is a dangerous illusion to believe that such a thing is even possible. The opposition of future to past or past to future is absurd. The future brings us nothing, gives us nothing; it is we who in order to build it have to give it everything, our very life. But to be able to give, one has to possess; and we possess no other life, no other living sap, than the treasures stored up from the past and digested, assimilated and created afresh by us. Of all the human soul’s needs, none is more vital than this one of the past.” - Simone Weil, The Need for Roots

Spaces of memory

The ongoing struggle for history in Spain is fought above and below ground.

(Otero Verzier, Marina.2018) Mass graves are a powerful symbol and a symptom of our past, only in Galiza there are approx. 461 mass graves of Franco’s repression, and according to data managed by the Ministry of Presidency and Democratic memory, only 27 have been intervened. Between 2005 and 2018, the land has returned to the descendants – and to the memory recovery col-lectives that have carried out these exhumations – a total of 75 victims.

(S.V. Pontevedra.2021)

I like to fantasize that she notices

every time I laugh or answer her, that the effort I put into the trembling of my walls and the cracking of my tiles isn’t in vain.

She likes to read her books out loud – to me. From Virginia Woolf and Ursula K. Le Guin to some very questionable fan fiction choices – for some reason, she is into vampires. But we won’t be getting into that right now. The thing about the readings is not only her soothing voice and the stories she tells me, but the fact that she sits down, takes off her shoes, and grounds herself with me. I can feel her warm touch and for this moment, we belong together, we become one. Her hands go through my scars as she tells me about Neville’s bee, and I only wish I could tell her everything I know.

Based on what I am telling you, it would be normal to think we know each other pretty well. But she only knows my surfaces and some of my noises. And sadly, I only know the sound of her voice, her reading, her eating habits... her movements, and the directions she takes. Everything is different from my perspective. I am motionless, often overcrowded, I get wet, and I dry out. I am old and new, and as I grow, I simultaneously crumble a little bit more every day. I am in constant change although it isn’t my decision to do so. My cells change, my body alters. At the end of the day, my agency belongs to others. They dress me up, put makeup on me and cover my scars. I often wonder if they are aware that by doing so, they are covering their own. That my scars are of them. Not only because they made them, but because they speak of, from, and to them. Through my gaps I can tell many stories, but only if you’re willing to hear them.

Next to the mass graves, another form of repression called “fondeamentos” took place. They refer to points in the sea, preferably in the estuaries, where the bodies of the victims were thrown. One of the most significant is located in the

Memorial in a place of fondeamentos. Vigo, 2006.[9]

Cartography of places of repression.Ourense.[10]

However, the regime did not only focus on making victims disappear, on the contrary, the main goal was to the murder of high-ranking citizens, making sure they spread terror. This is how the places of repression were born – they are public spaces where mass killings and torture took place. Currently, the research project Nomes e Voces has registered more than 300 places of repression that society has started to establish as places of memory, making public the private and neighborhood memory that had been hidden until now.

(Fer-nandez Prieto.2010) The ultimate goal for these places of memory is to create public spaces of togetherness where to re-work the past and pay tribute to the victims.

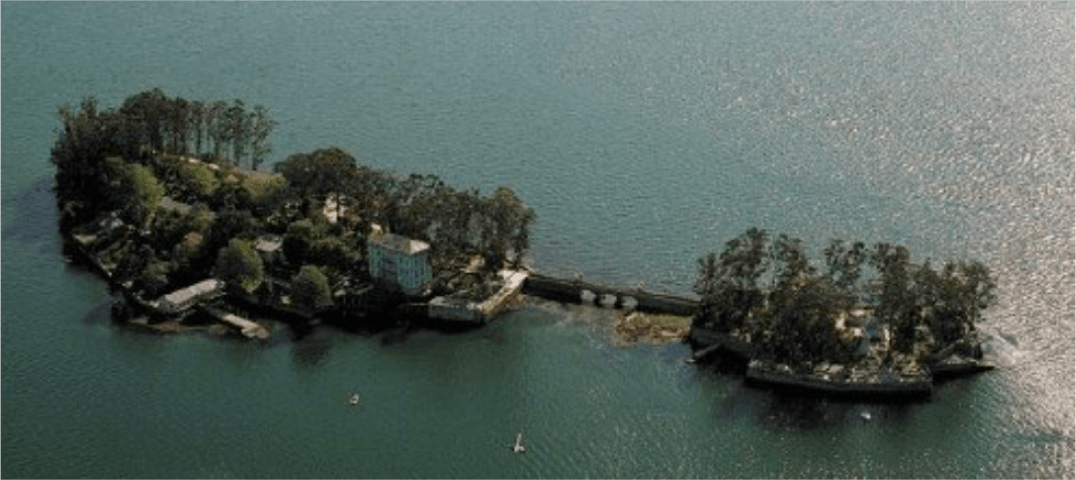

As an example of a place of memory, the previously mentioned island of San Simón is located inside the cove of the Vigo estuary. During Franco’s dictatorship, it became the most feared penitentiary center of the regime, from which it was said that “no one came out alive”.

That’s what I was hoping from Vee:

To hear me, so I can tell her about that time, the one very few people remember as of now. The time when all my ornaments and plaques come from. It was a time when mouths were shut down with violence, my insides were soaking wet with blood and some of my outsides looked very different. I know I often nag about being overcrowded, but back then I was constantly sharing the few spaces I had left standing, with others. Not because they were passing by and enjoying me, but because they had nowhere else to go. I became their shelter or their hell for that matter. For 40 years, I was charged with silence and fear. I have always thought the violence wouldn’t apply to me, but I found myself in the midst of it all. Despite all consequences, some people were willing to come by and place their memories within my gaps. Others would perish through time and illness within me, not before leaving their marks on me. Everything they knew, their experiences... their hopes, and their fears.

All became part of my landscape.

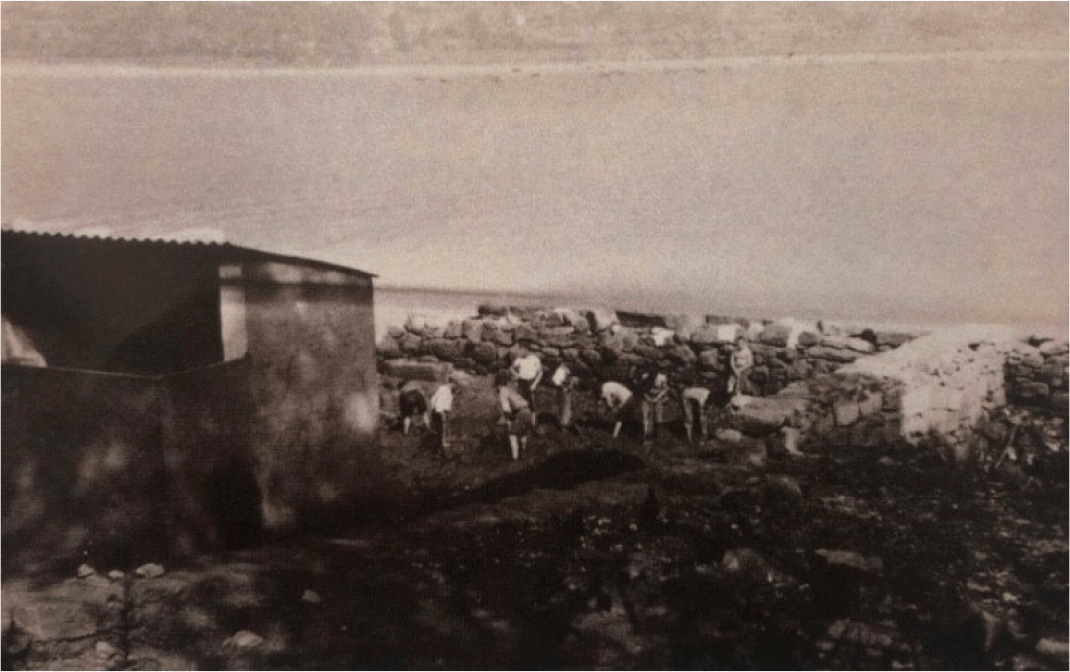

The island of San Simón was considered by Francoism as a that was later transformed into a concentration camp for political prisoners until 1943.

(Bluscus)

After being abandoned for more than thirty years, its rehabilitation efforts started in 1996, three years later the site was named “Property of Cultural Interest” with the category of a historical site. Following its intense 12 years rehabilitation, the enclave was renamed as Illa do Pensamento or Island of Thought, announcing it as a center for the recovery of historical memory.

(William, Meggy.2020) Consisting of a museum and a cultural space, as of today, it centers on the production, reflection, and creation of new collective memories while seeking to pay tribute to its past. Making it clear that the agency of its maintenance and the collective memory linked to it lays on the social engagement with the site. And that the re-working of such sites should be an act of renewal without forgetting the past.

Prisoners of San Simón island.[11]

Aerial view of San Simón.[12]

On the other hand, while in other parts of the world fascist monuments are brought down by citizen’s direct action, in Spain they are subject to periodic burial and unearthing. The impunity of Francoist crimes renders the public presence of the monuments that celebrate them even more controversial.

(Otero Verzier, Marina.2018) In 2022, the government approved a new Historical Memory Law, whose main premise is that "forgetfulness is not an option for a democracy". The law contemplates various actions for the reparation and respect of Franco’s victims, one of them being the total removal of symbols and monuments exalting the dictator-ship in public spaces.

I lived in silence

only because I wasn’t able to communicate yet, but I remember it all. It is all in me, every little scar, gap, and unturned stone, every ornament, plaque, and sculpture that you so often walk past by but cannot yet see, they are all keeping a memory. Telling the story of many. For a long time, I have been angry at myself for not being able to speak up, and for letting them silence me. And so, at the right time, I started crumbling, I stopped trying to carry the weight on my own so that you’d be able to hear my cries. Hoping that as I slowly perish, you start living.

And so, on the third day of the third week of my third year having lunch with Vee, she lifted a stone, and it became the first one of many.

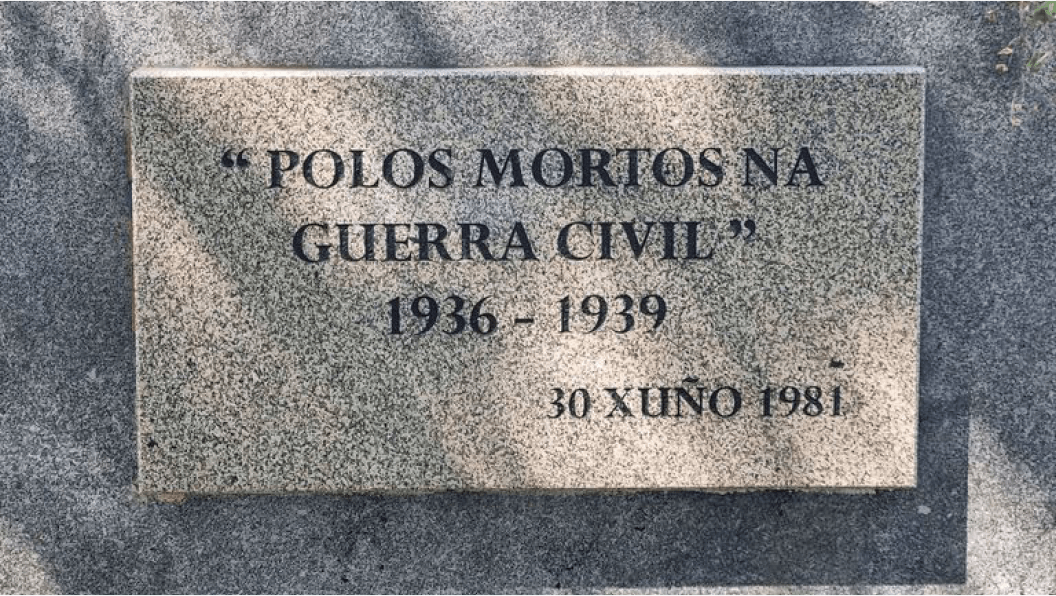

However, as of today, in Galiza there are a handful of monuments still standing with the pretext of “lacking a clear exaltation to the dictatorship”. That is the case for the cross on Mountain O Castro in Vigo. Where its shift in meaning from a monument for the regime to a memorial for the victims, is considered achieved by the removal of its Francoist slogans and the addition of a commemorative plaque. Like this, failing to recognize the pain and violence such monument still perpetuates on civilians, while gaining a sense of detached sympathy.

O Castro mountain cross.[13]

Close up of commemorative plaque.[14]

As stated by John Patrick Thomson in his interview on Memorializing Trauma: “the experience offered by memorials is completely public” however it isn’t equally experienced. To ignore the need for critical reflection on how our own privilege intersects with the suffering of others is to abandon our responsibility to those who are less fortunate. Therefore, all notions of restoration and social engagement toward these spaces should serve as a collective act of resistance and closure. And although Quetglas’ proposal proposes that “fascist monuments shouldn’t be preserved for historical purposes, on the contrary, they should be destroyed by a collective direct action – as a public celebration of the repression’s dismantlement” (Otero Verzier, Marina.2018) is of enormous relevancy, the importance of its renewal value should not be taken for granted. The collective re-interpretation and re-purpose of monuments, hold the potential for a profound process of self-examination and critical reflection. Something that is of extreme need within our society, as it helps us understand and avoid the creation of the same conditions that allowed the violence to occur in the first place.