“Everyone, like an atom in a nucleus, is encased in the impenetrable armor of solitude”, writes Georgyi Ivanov in his poem ‘Raspad Atoma’ –The Decay of the Atom. 9

The content of the poem talks with ruthless truthfulness and agonizing poignancy. It exposes the tragic contradictions of human existence and in a new, existentialist perspective, comprehends eternal problems of love and death, alienation, and the loss of the ‘hidden meaning of life’. The tragic pathos is the realization of the absurdity of human existence and the world as a whole. Thoughts about the inconsistency of traditional beliefs and the collapse of the foundations of European civilization illuminated by the centuries. In other words, it’s about how a heartbreak makes the world disintegrate and decay. Ivanovs revealed the world, showing its nudity and all its splendor of grayness, filth and hopelessness.

The disintegration started in 1917 for Russian artists10 , and ‘Raspad atoma’ is a guideline poem for the post-revolutionary literature of the 30s. The collapse of the world begins with the soul of an individual –the atom, which simultaneously symbolizes both the ‘little man’11 of classical Russian literature and the discreteness of the big world, realized by post-revolutionary literature– and ends with it. There is no salvation from universal disintegration: “The point, the atom, through whose soul millions of volts fly. Now they will split it. Now the motionless impotence will resolve itself with a terrible explosive force. Now, now.”

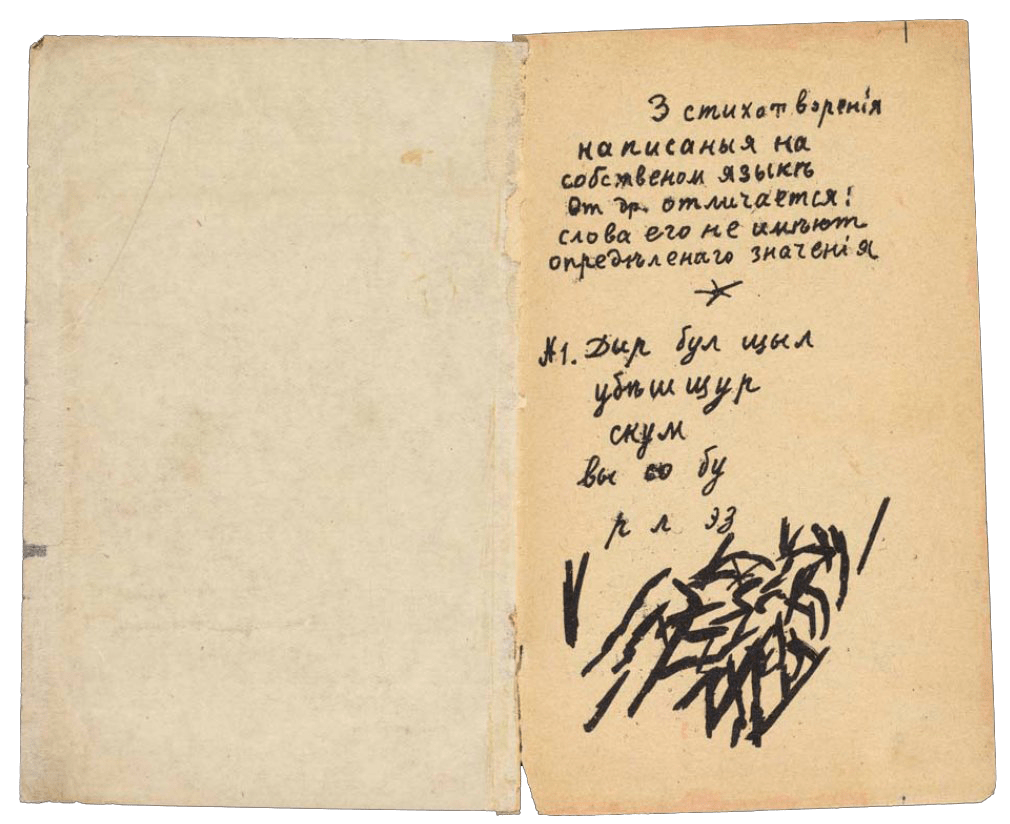

The other aspect of the decay in the poem is the decay of words and language, as he adds Aleksei Kruchenych’s ‘dyr bul shyl’. The soul, shrunk to an atom, speaking the futuristically sweet language of unknown beasts, falls apart. Thus, ‘Raspad Atoma’ creates a model of the universe as a decaying atom. Decay is understood not only as the socio-historical breakdown of the twentieth century, but also as an ontological law, originally inherent in the essence of being. At the same time, the theory of quantum physics –where physical properties are examined on a subatomic level– came into frame, where the concept of decay is applied even at the level of quarks. Here Ivanov points to the connection between Khlebnikov and Kruchenych’s ‘zaum’ and the decay of language. In this connection one cannot fail to mention the ‘Заумная гнига’ (Zaumnaya gniga, play on words –book in Russian is kniga; decay is gniyeniye). The decay of the word and sound is the best condition for the growth of thought, thus the book becomes “gniga”.

“Zaum”, the term refers to a literary phenomenon that crystallized in the era of Russian avant-garde literature –formalism. Members of the OPOYAZ (Society for the Study of Poetic Language), studied zaum as a technique that became the focus of poetic studies in the second half of the 1910s. One of the famous members was Aleksei Kruchenych. According to him, December 1912 should be considered the birth date of the ‘zaum’ language when his own poem ‘Dyr bul shyl…’ was written. He writes: “We began to see here and there, we dissected objects, we began to see the world right through”.12 Russian formalists call this language universal, free, abstruse or ‘zaumny’. It has gone beyond reason, and in their moments of supreme inspiration, rejecting all the customary speech that has developed in the culture of thousands of years. They resort only to it. They consider all meaningful speech to be false and powerless, since it cannot convey what the poet feels.

At the origins of formalism is Victor Shklovsky’s report ‘The Place of Futurism in the History of Language’. This raw, confused text formed the basis of his pamphlet ‘The Resurrection of the Word’ (1914), and then of his famous article ‘Art as a Reception’ (1916), which introduces the concept of defamiliarization. Introduced by Shklovsky and developed by representatives of OPOYAZ in the 20s –when studying the inner form and structure of the word– the notion of defamiliarization represented a radical change in the point of observation and in the mode of vision in the entire area of the expression of the artistic fact. Together they made a new science of literature that asked the question ‘How?’ immeasurably above the question ‘What?’. According to Shklovsky, the technique of defamiliarization restructures the field of perception: “not to bring meaning closer to our understanding, but to create a special perception of the object, to create a vision of it rather than recognition”.13 Since the goal of defamiliarization is to ‘remove the thing from the automatism of perception’, the procedure itself actually changes the perception of the perceived intention.

The universality of defamiliarization as an artistic device, noted by Shklovsky, is in fact identical with the notion of the ‘estrangement effect’ –Verfremdungseffekt– which was developed in Bertol Brecht’s theatrical aesthetics and artistic practice. According to Brecht, estrangement not only places the depicted in the position of unrecognizability, but thereby activates the perceiving person to overcome his or her own subjectivity. In Bertolt Brecht’s Theater of Estrangement, the spectator doesn’t pay any more attention to the ‘what’ but only to the ‘how’. The spectator must observe the course of life, draw appropriate conclusions from the observation, reject them or agree with them, he must be interested, but –God forbid– not be moved. He must consider the mechanism of events just as he would the mechanism of a machine. In other words, ‘exposing the reception’, ‘showing the show’.

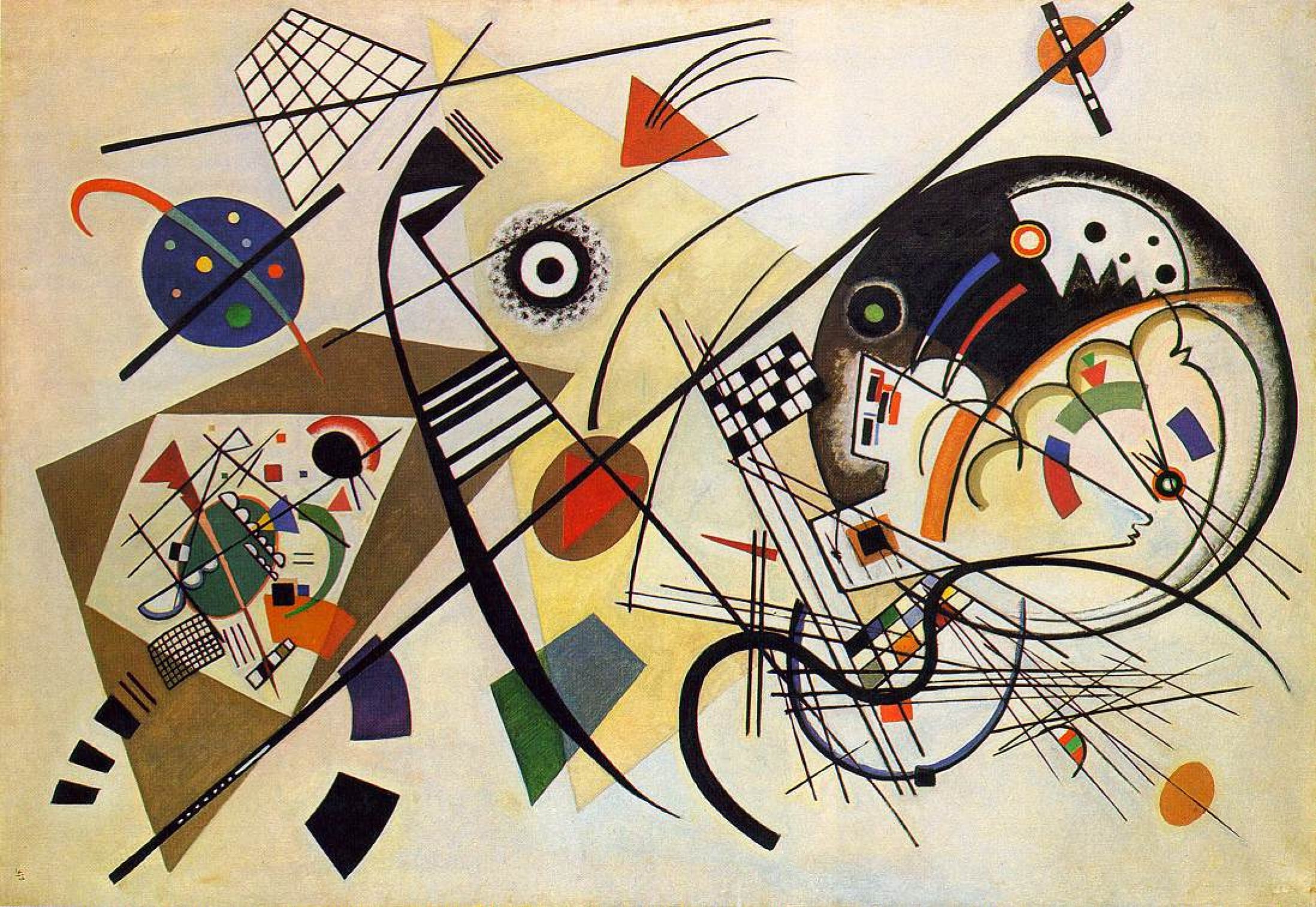

Pavel Filonov expresses similar thoughts. He proposed the idea of the ‘atomistic structure of the universe’: “Creativity is hard work on every atom of the thing being done, no matter how dry, stale, poor and even repugnant its so-called mediocrity. Every line must be made. Every atom must be done...Think hard and precisely about every atom of the thing being done”.14 It is not only the creative process that should be analytically active, it should also be its perception, which is why the masters of analytical art often do not give titles to their work, thus activating the intellect of the viewer. The picture should speak for itself, it should provoke the intense work of the intellect, which without any prompting from the outside is trying to understand what is written.

Another new to the twentieth century view of the world was outlined by Henri Bergson in his 1907 book ‘Creative Evolution’. The subject of study in Creative Evolution is the life of human consciousness. As the main characteristics of consciousness, Bergson defines ‘duration/temporality’ or continuous changeability of consciousness. Duration is also an attribute of time, which he understands as ‘living’, subjective time. Nature and the world unfold by constantly being in flow. This reading was captured in the avant-garde. Abstract painting is the only adequate way to capture, reproduce, and show the flowing essence of what is happening. A dot, a line on the surface as we can see from Kandinsky and Malevich.