Equipping

Quarry in Jaworzno, Poland

Two scuba-divers submerged in water

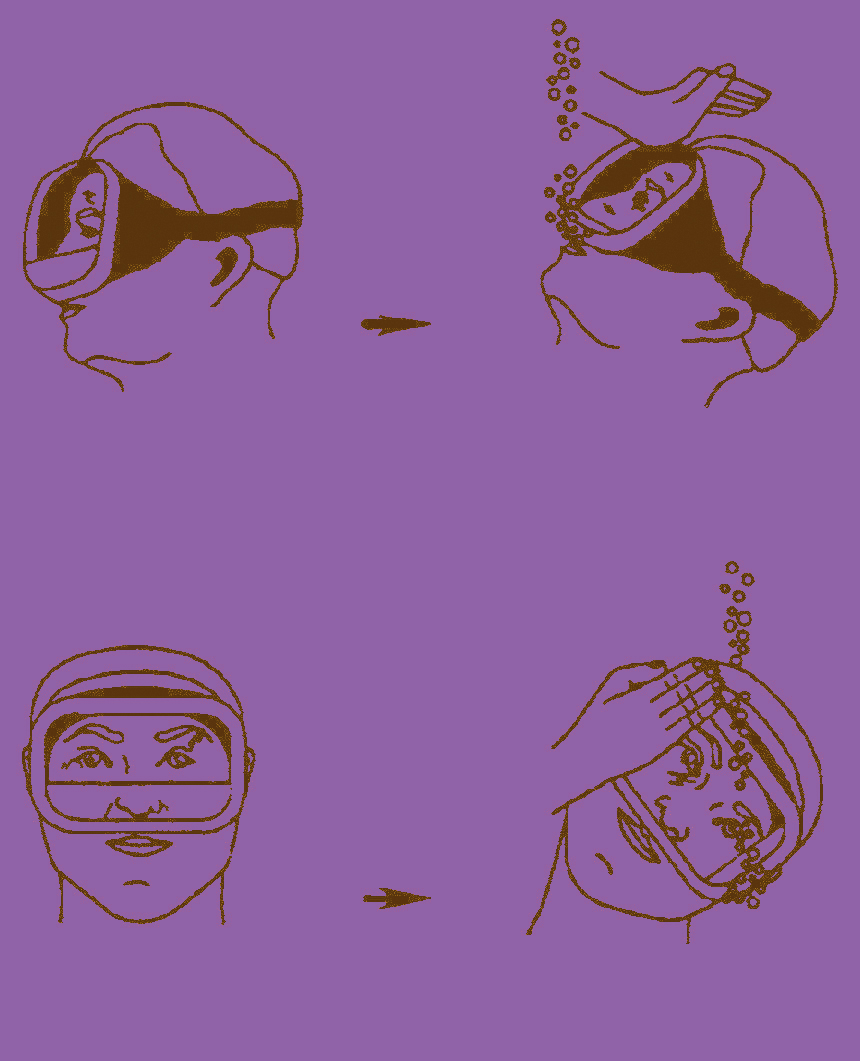

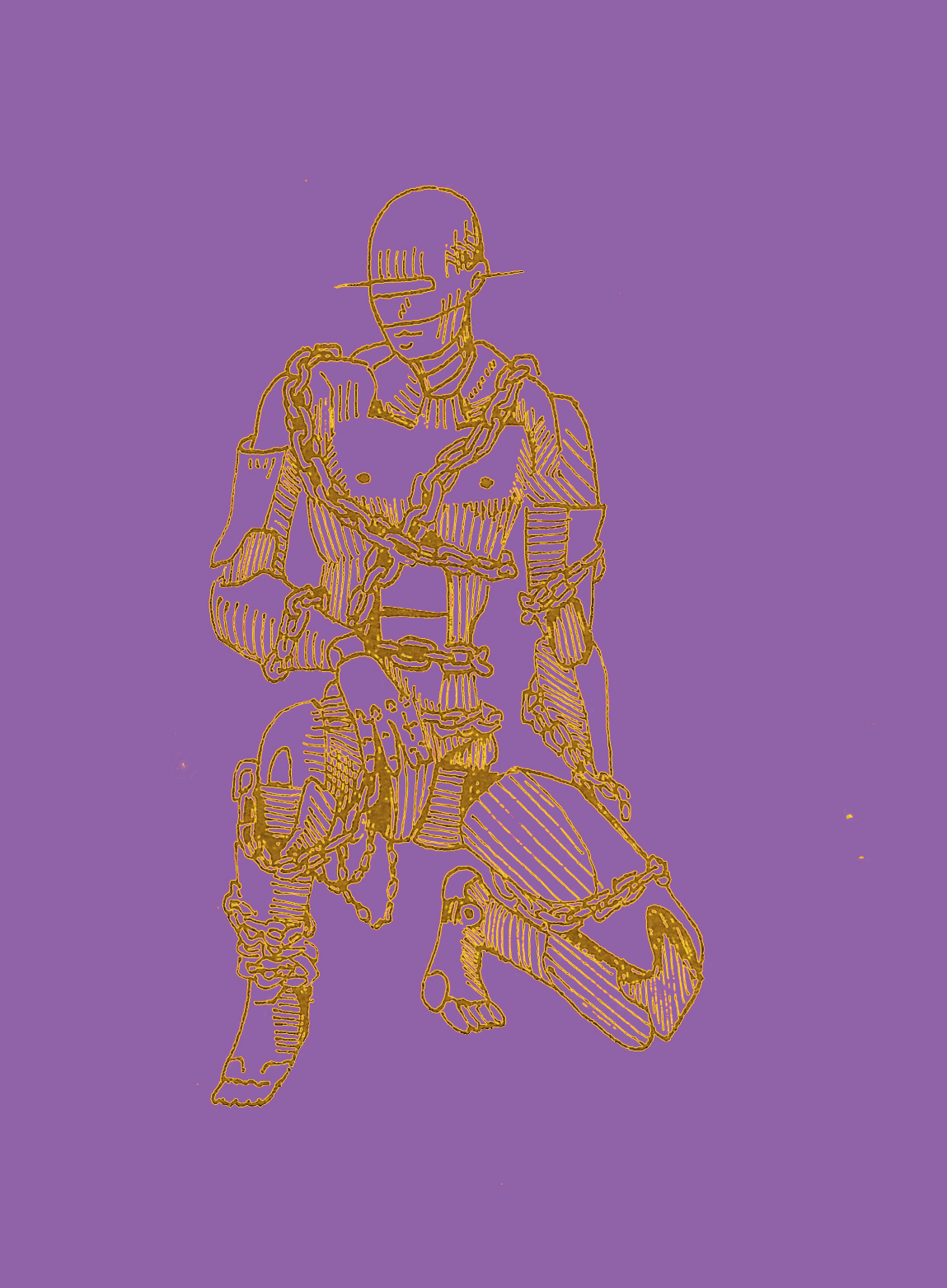

Equipping

The divers arrive at the location where they are going to dive. It’s a quarry in Jaworzno, a city in the south of Poland, once a site of exctraction of cement and dolomite plant. The quarry and its walls are made from stones, metals, clay. Due to the lack of payment for the electricity bills, in 1997 it was filled with water in an overnight action. While the power supply was cut off the water pump stopped working and all of the equipment sunk. The water pump would suck the water from the ground and relocate it kilometers away from the excavation territory. Now, it is a site for divers, a container for water and a dumpster for the equipment that previously had shaped it.

Two divers meet. They start unpacking hard-shell bags for storing their diving equipment. Inside are diving masks, snorkels, wet or dry suits (body armors of black rubber), gloves, scuba tank, regulator, dive computer, pocketknife, flippers, weight.

First, they gear up first themselves later double-check on each other; to see whether they haven’t missed anything or if something isn’t hanging loose from their backs (as that’s beyond the diver’s reach, vision). In the end it’s a lot of gear to put on your body so getting ready carefully and methodically and at the same time as your buddy are the key to feel safe and reduce any pre-dive stress.

Carrying

Carrying

Geared-up divers must carry everything by themselves, now weighting additional dozens of kilograms, to the water. The moment you reach the level of water deep enough to hold you it will take the weight off the legs and the back keeping the diver’s body on the surface. As long as a jacket (buoyancy compensator) is inflated the air will balance the weight of the body, the equipment and the extra weight put on a belt tied around a body preventing the diver from drowning. It’s the moment the diver can once again, after this exertion, rest and be held by water before they descend.

In the context of sports, we can learn about two modes of body consciousness that can occur simultaneously and fluctuatingly in different parts of the body at any one time. The modes in question are dis- and dys-appearance, both relate to how much aware and considerate we are of bodily functions and perceptions. While the first one–dis-appearance–"is akin to (parts or all of) the body vanishing, or a forgetting of the body as it operates seamlessly – functioning appropriately for the surroundings and the task at hand,” the dys-appearance, by contrast then, “is associated with awareness, an attention to movement, visceral functions and bodily co-ordination. It is the mode of being which is apparent when we are away from our usual surroundings and/or we are required to act and negotiate our way around space in novel or previously unrefined manners” (Merchant 218). For example, for divers, while submerging, the re-arrangement of the sensorium follows and that in itself, creates a space to reflect on “unrepresentable” senses that can be associated with the dys-appearance (discussed the most often in the context of illness).

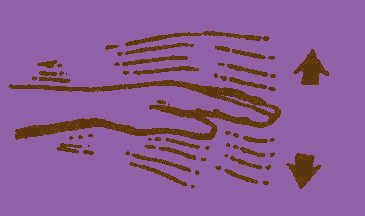

#Signalling

TAKE IT EASY OR SLOW DOWN

YOU LEAD, I’LL FOLLOW

#Signalling

Already arriving at the moment before submersion, the communication between the divers switches from verbal to non-verbal. From now on, it’s the hand gestures, it’s each other’s bodies that they have to make sense of by reading, interpreting, responding to. The divers enter the world like the one created by Octavia Butler in a 1983 ¬sci-fi story Speech Sounds. Butler pictures a dystopian world where characters have lost the ability to speak, read, or understand language. This scenario offers a view into monstrous forms of what’s left of communication. Similarly for the divers even though they have a some agreed upon signs of communication, at times of disfunction, or encountering what they can’t be prepared for, the improvisation and close reading of each other’s body language is crucial. Hence, the sense of vision becomes particularly highlighted. Visual checks are important, especially the ones you do on your diving buddy giving them a metaphorical handshake, as in a “decided ritual of both asserting (I am here) and handing over (here) a self to another.” (Rankine 17-18) In the end, the person you submerge with you need to trust with your life and assert them that they can trust you.

Entering the water is entering a state like one of an “illness”. The divers struggle, get weak, panic, experience being a fragmented body only to but also emerge to the surface with a newly possessed knowledge. There are many similarities between this world the divers inhabit and that of Octavia Butler. Both are, on which I touch upon later in the text in relation to the space of water, very distinct acoustic realms. Butler’s where the disease has rendered the activities of speech and listening mutually exclusive, and water where the divers attune to a fully recalibrated sensorium and are trained to constantly doubt the so-far silent, straightforward, and reliable functioning.

Butler’s world is the ruins of civilization which was severely affected by a fatal and unnamed illness. People communicate among themselves through universally understood sign language and gestures that can often exacerbate misunderstandings and conflicts. Bodies, in a way, replace words. In a fantastic response to the text Nikita Gale writes of this world as such:

“Speech Sounds” places us in a world of bodies. The bodies in this world whistle and applaud. They scream and squawk and roar and whimper. They all seem to carry guns. Facial expressions “disintegrate” as bodies throw punches, fuck, spit, cry, and bleed out. […] Communication has retreated to the visible body. That space between bodies formerly designated for speech and listening has been removed entirely. Language has been replaced by paroxysm and elaborate physical gestures that stop “just short of contact.” In this world, the body is the word and text by which meaning is produced and received. (Gale 463-464)

The spit, the cry, the bleed out it yet to appear in the text as the divers proceeds to the next stages of a dive and cover themselves in ambiguity of a new environment. Because the disease in “Speech Sounds”, just as a body of water is environmental. What it seizes from bodies is language. But what it offers is the space to be in relation to one another. The fact that the actors are rendered “clumsily signifying objects” (Gale 464) helps them operate from a non-authoritarian position; but instead from a porous, attentively attuned.

Submerging/Sinking

Michaël Borremans, The Pupils

Submerging/Sinking

[C]aught struggling against some circular undertow, facing the panicked compartmentalization of the body as a single leg or hand or head momentarily rises above the liquid surface and then slips beneath again...until the point of total

surrender is reached.

Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Omnicide: Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium (245)

Communicating vessels

A body of water is in a constant flux, its body is affected by many forces that themselves are a subject to constant change. One could argue along with Kamau Brathwaite, that linear or progressive thinking, or the logic of undisturbed development doesn’t apply to the underwater space which requires being in constant negotiation. It is a reactionary approach, one that Kamau Brathwaite calls for in his tidalectics. If dialectics describes how “Western philosophy has assumed people’s lives should be” (Hessler 33), tidalectics recognizes what is missing, which is the fluid dynamism and transformative aspect of water. The cyclical movement of the sea makes us think beyond binary conditions like regress or progress. Brathwaite’s tidalectics “[dissolves] purportedly terrestrial modes of thinking and living, it attempts to coalesce steady land with the rhythmic fluidity of water and incessant swelling and receding of the tides” (Hessler 31). “The tides” as a metaphor has been used extensively by Kamau Brathwaite to incorporate rhythmical structures into his writing. In his use of language he embraces the idea of shifting order and belonging of human and non-human agents, a disruption that might bring re-arrangement of roles between the bodies and its temporalities. While submerging tides and currents we might be helped in movement we intend but we might also be pushed back—and that’s where the negotiation takes place, it’s where we attune to a different kind of vocabulary.

Our land-based embeddedness and terrestrial “obsession for fixity, assuredness, and appropriation” (Hessler 32) has grounded us in position that is in an imbalance with water. Accustomed to the habitual security the land offers us we fail to imagine terms on which we could co-exist with such vast body that is an ocean. The acts of letting go and submerging have been relied upon by Astrida Neimanis to construct “hydrofeminist” perspective. This perspective considers states in which there is nothing to hold us, where becoming “tetherless” disturbs the traditional understanding of some of our holding patterns. As we start experiencing weightlessness, “we find ourselves tangled in intricate choreographies of bodies and flows of all kinds—not only human bodies, but also other animal, vegetable, geophysical, meteorological, and technological ones; not only watery flows, but also flows of power, culture, politics, and economics” (Neimanis 111-112).

The idea of detaching from some of our comforts means operating from a vulnerable position. “Submerged in the water, we can explore (or rediscover) a new sensorium”, writes Hessler, to attune us to the re-arrangement of thinking and knowledge of bodily capabilities and function water can teach us.

Equalizing

Clearing a face mask

Protective Clothing

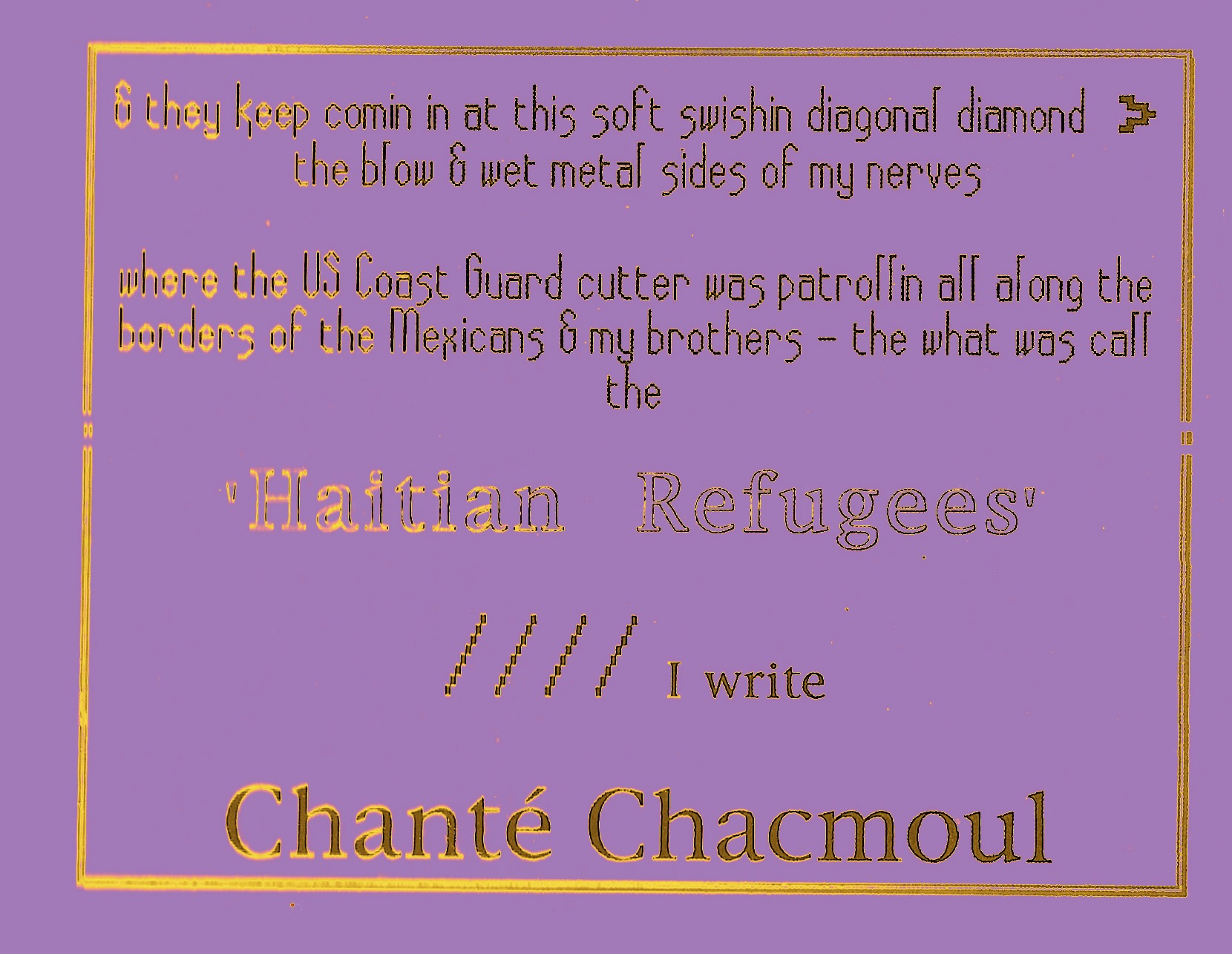

Dream Haiti by Kamau Brathwaite

Equalizing

Descending into the depths, the divers experience pain due to the sudden change of pressure. “The deeper the diver goes the more pressure is put upon the body, an environmental stimulus which tends to manifest itself in the ears, the mask and the sinuses.” (Merchant 13)

To easily illustrate this reaction its simple enough to think of an empty plastic bottle with a spout. When you descend with it the air will compress and the bottle with start shrinking. If that pressure won’t find any outlet it will puncture one of the walls filling the vessel with water. The same happens to your ear drum when the pressure is working on it. To equalize you would blow your nose to let more air in, just as you would blow some air into the spout of a shrunk bottle.

The first moments of the dive are full of nuance for the human body. The diver learns to react to the environment by adjusting the equipment which is there to provide the diver with oxygen as well as to allow access to senses like vision, which underwater wouldn’t function without a mask on. However, the state of equilibrium that can be reached as the result of calibration between the body and technology parts, happens only through the constant adjusting and equalizing. For example, when the mask that covers both the nose and the eyes gets foggy or leaky the diver needs to open the plastic seal of the mask and fully flood it before blowing through the nose to refill it with air. It’s often the case the diver will have to let in/take in what they try to get rid of before finding themselves back in balance.

“The practice of ‘equalizing’ must be learnt in order to fill the body-equipment spaces of the ears and the mask.” (Merchant 230) The balance between the pressure of the inner ear and the pressure at certain depths.

This ties to the topic of my thesis, the dependency and the negotiation it suggests between the local and the global body. The concept of communicating vessels illustrates it well. Remember how the quarry got sunk overnight when the water pump stopped working. The failure of technology let the already weakened body of nature balance itself out (communicating vessel) with the larger body of the sea, of the ocean. It’s quite similar to how the equalizing ear that is descending in water works. The diver is able to equalize the pressure in the middle ear with the surrounding water pressure by adding or venting air through the eustachian tube. Once the pressure on the outer ear is too high it might rupture it. It can also happen from the inside of the body. Blowing too hard with a blocked eustachian tube increases pressure of the inner ear fluid which can blow out the inner wall. (Gibb) In any case, if not equalized properly, the internal organs of the diver get flooded. This might lead to an immediate feeling of vertigo, possibly accompanied by nausea, vomiting, buzzing, ringing ears or hearing loss.

These processes show that bodies will equalize despite whether you allow it or not. The body underwater is a site to these constant changes and in such conditions the diver experiences intensively internal body noises, not consciously made, yet produced nonetheless, that in an muffled watery environment, troubles the unity of the body and hinders the hearing. These sounds are being described by divers as “ticking” or the “high pitched ‘eeee’ noise” (Merchant 229), bowing bubbles or making an “aaaaah” noise when resurfacing. These new, previously imperceptible or unheard sounds of internal bodily movements, reactions and processes become audible. “Such aural intrusions can rupture performance and are the result of the diver’s primary auditory receptive mechanism shifting from air to bone conduction.” (Merchant 227) One of the Merchant’s research interviewers described it in such words:

Oh God, I thought I was going to die, as we descended I could hear this high pitch squeak coming from my forehead and it felt like someone was stabbing a knife through my brain. This ‘eeeeeeeeee’ noise kicked up an octave, sounded like the noise a radio makes when you tune it, and then suddenly it stopped as I felt a blob of liquid come out of the corner of my eye, then it was gone. (Merchant 227)

The sound becomes one of the only ways in which the body communicates the state of being.

Altering

Engraving of Halley’s Diving Bell

In Service Of A Song, footage still of Pan Daijing's performance which is a musical work without sound as it’s happening inside a soundproofed structure. Pan Daijing was the only living organism to witness the performance from inside.

Altering

When human body becomes one in the fluid environment, the hearing is the first sense to be developed. This newly experienced sensations (of the state of submersion), come at surprise for the divers whose hearing has been since recalibrated to be receptive to how the sound travels through air, as oppose to the liquid. What the diver experiences audibly in fluid environment is amniotic fluid, which Sophie Lewis explains as:

[It] is initially a mix of water and electrolytes and later sugar, scraps of vagrant DNA, fats, proteins, piss and, often, shit. As pre-borns, our embryonic mouths, noses and lungs are filled with this ‘liquor.’ (Lewis)

For the diver it is a very uncanny experience which one needs to get used to or surrender to. In Lewis’ text Amniotechnics she even mentiones that “some [..] deepwater divers will try to slow their heart-rates by ‘remembering’ this time before fear—this state of non-antagonism towards water—to calm themselves enough to perform their tasks” (Lewis) The hearing underwater becomes something new as it is nearly impossible for humans to use underwater acoustic vibrations to locate themselves in space. The reception of the sound travelling in air by the left and the right ear independently–what we understand as the “stereo” effect–underwater “it’s largely registered by bones in the skull” (Helmreich 624) which renders the hearing as “omniphonic–coming from all directions at once (and, indeed, because of sound’s seemingly instantaneous arrival, often as emanating from within one’s own body).” (Helmreich 626)

If one were to experience their own body through water similarly to how I described it above, it might change the way we relate to our bodies and the bodies of water, like an ocean or the sea. These intensities make me think of how unjustifiably the deep is often considered quiet, mediative space. The ocean floor–the domain Jacques Cousteau (with Dumas 1953) once named “the silent world” is all but that; or maybe, to be more precise, to experience it deeply and be held by it is an extremely sonorous experience as we let ourselves listen to the other body through heavily affectious mediation of its all-the-time changing conditions.

The reception of sound immediately and intensively through bones creates something else than a soundscape, which the diver is accustomed to experiencing above the surface. Helmereich writes about this difference:

[T]he underwater world is not immediately a soundscape for humans because it does not have the textured spatiality of a landscape; one might, rather, think of it as a zone of sonic immanence and intensity: a soundstate. (Helmereich 624)

The soundstate here is understood as that bodily experience through sound, along the redundant new role of hearing which perceives sounds more as ambient noise than a form of communication.

This is a great example of what unlearning can resurface. It’s a practice of attunement to a hidden realm, which just us an underwater realm, humans cannot have an extended or unmediated access to. It’s allowing oneself to be transformed by water in a way that doesn’t lead to a full grasp and understanding of it but instead makes the diver realize how this tetherless state produces “fragmented” knowledge about both you and the bodies in your surrounding that you are always in relation to but might not let yourself be affected by it.

Breathing

Dream Haiti by Kamau Brathwaite

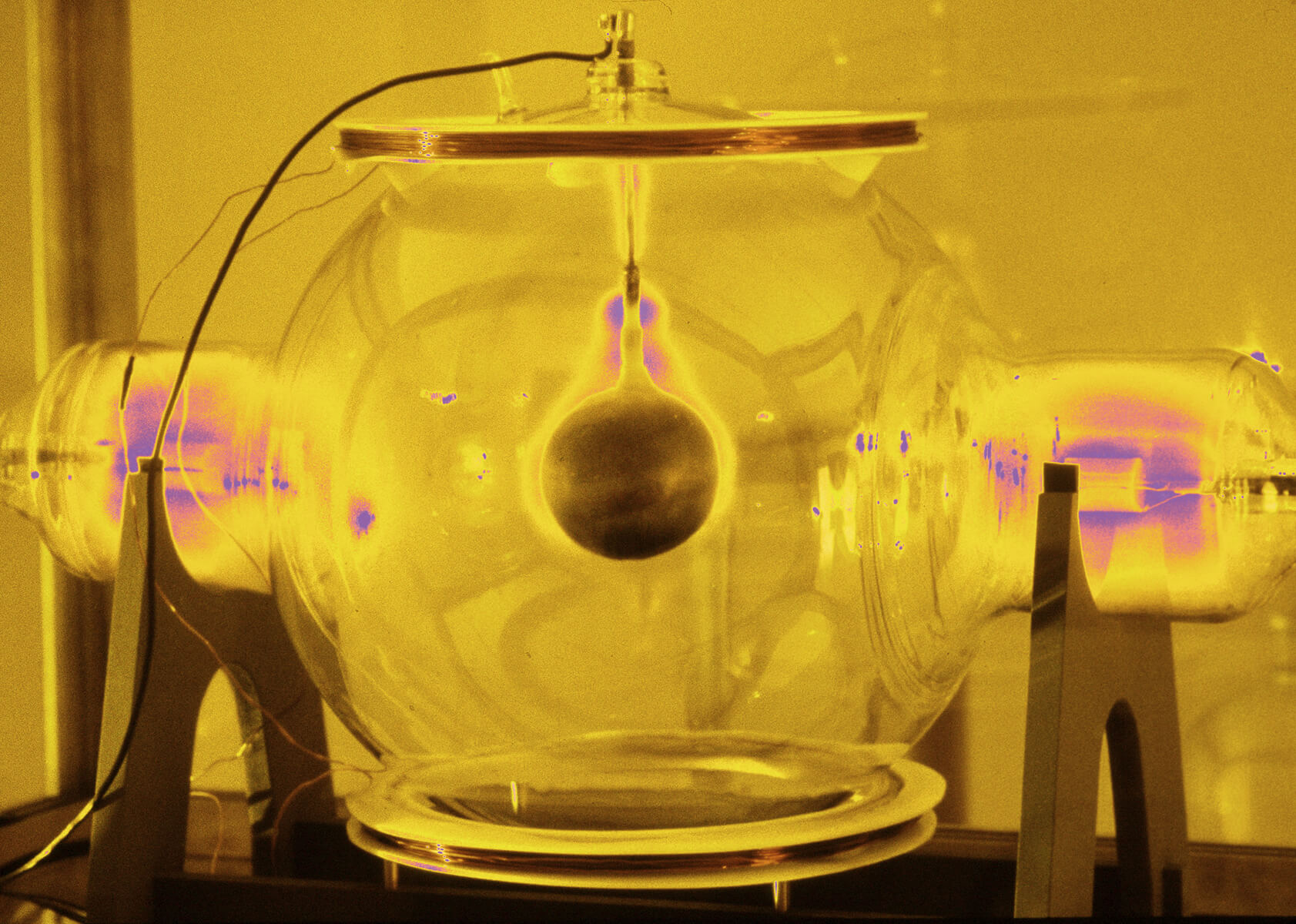

Charged Hearts by Catherine Richards

Opening illustration from An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics 'WE WANT IT ALL' edited by Andrea Abi-Karam & Kay Gabriel

Assyrian Frieze (900 B.C.)

Early Impractical Breathing Device. This 1511 design shows the diver’s head encased in a leather bag with a breathing tube extending to the surface.

Breathing

Just as the hearing gets altered, sense of touch, undergoes alteration. More than the diver touching, the diver is consciously being touched by the surrounding, as well as felt by equipment, for example the wetsuit against the skin. “The constant contact between the materiality of the suit and the body works efficiently yet silently, beyond conscious thought.” (Marchent 225)

The wetsuit becomes the second skin for the diver, through which they are constantly caressed by the environment of water, movement of the tides, turbulence, other organisms, as well as rising pressure and changes of temperature. And this is precisely what early cyborg theoreticians Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline meant by defining cyborg body as an “organizational complex functioning as an integrated homeostatic system unconsciously.” (Helmreich 629) We can acknowledge here that the divers’ bodies extended with technology find a way to enter negotiation with the unexplored and the invisible, as cyborg bodies.

Every tool is a blind man’s stick, an instrument for reading, and every apprenticeship is a learning-to-read in a particular way. The apprenticeship finished, meanings appear to me at the nib of my pen or a sentence appears in printed letters. (Weil 13)

This brings us back to writing of Brathwaite and Neimanis who have paid a lot of attention to interruptions and breaks in and of watery bodies. Brathwaite, in his writing brings forth the new syntax that disrupts the linear cause-and-effect narrative. Similar measure in poetry is often referred to as caesura–a rhythmical pause in the middle of a sentence or poetic line; a breathing interruption that occurs in the natural rhythm of the speech; a fracture in the language that breaks the sentence in two distinguishable separate parts that are yet intrinsically connected. The linguistic approach of Brathwaite, next to the more embedded one of Neimanis, play with these interruptions searching for the spark of newness, that when attended to, the body can re-shuffle sensual perception, alter the sense of embodiment and landscape.

Why I write about the cyborgs and the bodies is to look at the ways the body, extended through prosthetics, finds itself thinking less and less the more it engages with the environment. The moments of disappearances are the ones that make you experience the environment at the deepest level which has prolonged effects on how you engage with your everyday environment. Unlearning happens in destitution , which destabilizes notions like clarity, full understanding, the certainty.

The immersion in water, because of its density and high pressure, gives a sensation that can be compared to hovering, or flying. Hence, travelling through and inhabiting space underwater, requires from the diver the application of alternative ways of navigating with the use of their own body. In case of the scuba diving that always happens in relation to the technology carried with, the body of your diving partner as well as the environment and conditions of the body of water.

Already during the first dive, new knowledge is produced, for example, when the diver realizes that breathing can be used as a tool to adjust their position. “Controlling body positioning underwater is related to the change in volume/density of the body over the course of a dive, which can be controlled on a small scale by the lungs.” (Merchant 228) Intaking air leads to the body ascending, exhaling brings it down—the working together of the two gives the divers the ability to stay level in water. For the novice diver, as long as they are to concentrate on the slow, deep and regular breathing they are able to maintain that state of balance. However, encountering an obstacle, i.e. a fellow diver who you might need to maneuver around to avoid crashing into, an animal or plants/coral reef that often leads to a panic, spontaneous reaction that would be in this case repositioning with the use of BCD, then immediately an over/under-inflated BCD hinders kinesthesia and that disruption into integration of the body and the equipment becomes a source of dys-appearance. With time, however, the constant interpretation of new causes and effects leads to the embeddedness of these tidal movement as a memory of the body, one that is similar to that of navigating the body on land. The evidence of that can be found in the diver finding their own new way to integrate their lungs and technology. The dis-appearance manifest itself in freeing the diver from making the inefficient adjustments to the equipment, reacting in a more immediate way on a smaller scale with the breath only.

A diver is half machine half human, without the machine, the diving suit, diving into deeper depths for longer periods of time would be impossible. The diver is the cyborg body, at times functioning as the “integrated homeostatic system.” In Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway writes about cyborg bodies as tools (for thoughts) that oppose dichotomy and address dualism. The cyborg–“a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Haraway 5) Haraway’s framework spans over divides like culture nature, mind-body, nature-technology which can help think of diving as a reflection on the value of perceived confusion of the borders of those categories and how they can dissolve into one another. As Helmreich put it: “the boundaries of cyborgs are subject to shifting and expanding as they are networked to other feedback dynamics across scales and contexts” (Helmreich 628) Considering this and thinking through the conditions of the watery body, these boundaries are even more prone to being affected. Here, precisely in this moment of diving, the separation of body, mind, and nature are overcome.

There is another new relationship of the dive equipment in relation to the rest of the body that can be discovered in this state of weightlessness. For Haraway, the “[c]yborg imagery” expresses “taking responsibility for the social relations of science and technology means refusing an anti-science metaphysics, a demonology of technology, and so means embracing the skillful task of reconstructing the boundaries of daily life, in partial connection with others, in communication with all of our parts.” (Haraway 67) This manifests the need to be particularly perceptive to what is around you–above as well as bellow, in front and behind of the body. The touch, again, is being recalibrated. On the land the proximity of objects, especially the ones tied to your body reminds you of its position putting weight on your body and being in constant friction and in response to your movement, thanks to gravity. Looking down would seem the most likely place to find bodily appendages, underwater, while the body being flipped, means you might find it floating around, getting hooked under armpits.

Already lacking the grounding nature of a solid underfoot, proprioception needs also to deal with a set of prosthetics, which must be internalized so that the diver can remember their location on the body and in space, in order to put them to use. (Merchant 230)

This work is done for yourself and your buddy since none of you grew the respectably flexible neck or arms that can reach the places behind your expanded-with-an-oxygen-tank body and the inflated jacket limiting the arms span.

Interestingly enough, Haraway’s cyborg theory is based on writing as “technology of cyborgs, etched surfaces of the late twentieth century.” (Haraway 57) Body of a diver, how it is not only a fusion of a human and a machine but also as a surface onto which new memory of the body is carved into. The transformation from dys- to dis-appearance, the new knowledge of a body brought to the surface. It can be thus concluded that not only the cyborg body of the diver is writing but the act of diving is that too. Writing is a good metaphor of feeling submerged–as an act of immersion into subject. The writing is gaining other symmetry like a vertical one of free fall. This way of experiencing both the diving and the process of writing creates a connection to that claim of Dona Haraway.

Cyborg politics are the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly, the central dogma of phallogocentrism. That is why cyborg politics insist on noise and advocate pollution [...]. (Haraway 57)

The cyborg body both writes and is written and in the process learns and changes, blends the boundaries. Haraway nominates cyborgs: herself, Sister Others, i.e. women of color, and a crew of women who are science fiction writers. “Cyborg monsters in feminist science fiction define quite different political possibilities and limits from those proposed by the mundane fiction of Man and Woman.” (Haraway 65).

As I wrote before, in Speech Sounds people find themselves exploring what a space of relation looks like beyond or before language. The new tools: the equipment, non-verbal communication, trust are exercised through densities of existences of a single dive. Nikita Gale writes that Speech Sounds is “an invitation to think about what happens to society when it loses a tool that not only locates a subject in relation to other but is also such a naturalized marker of identity.” (Gale 466)

Exploring / Levelling

found image of a jug in a contribution titled 'Postcards from the fringes of language' by Heimo Lattner & Judith Laub from a book Grounds for possible music: On gender, voice, language, and identity. edited by Julia Eckhardt

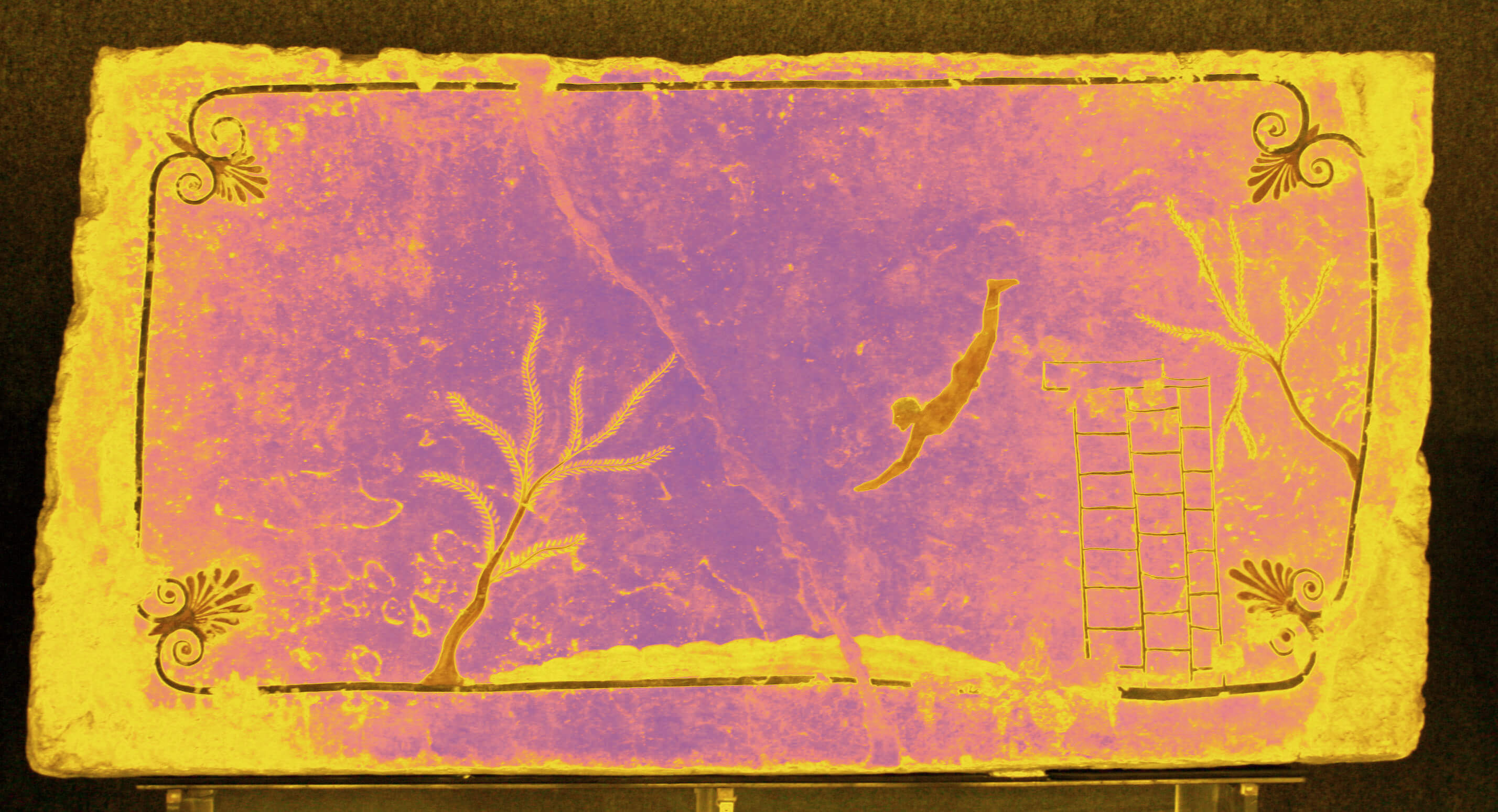

The Tomb of the Diver located in Paestrum. Built in about 470 BCE.

Detail from the underside of the top slab of the grave, showing a person diving into waves

Exploring / Levelling

“An event closer to possession, or to water’s pervasion of a vessel, a filling and mimicry of the other’s shape, a reception of its mould, with human identity […] becoming nothing less than vase, urn, or bottle.”

Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Omnicide: Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium (252)

For the purposes of this chapter I want you to have in mind a container made of clay, a material deriving earth’s crust and surface. “The empty space, the nothing of the jug, is what the jug is as holding vessel.” (Heidegger 167) In the context of diving, a quarry can become a jug. “The emptiness, the void, is what does the vessel’s holding” (Heidegger 167). Holding is considered here as an active process, hence, the object itself is an active entity, not a passive one. The container is an entity of re-sourcing–once it gets filled from a source it becomes a source of what it has kept and preserved. We can expand our thinking of holding as a process that is in a constant flux between taking, keeping and outpouring.

The bodies of water attended to by divers are understood as event landscapes, active entities–the moment we acknowledge them as such, we become agents in exchange ourselves—we enter a relationship in which in a reciprocal manner we care for each other, whether we submerge or cohabit in its surroundings. But beyond apparent human interference into quarry’s landscape, thanks to our understanding of a container, its context can be broadened. “The characterization of infrastructure in this discussion is twofold: it concerns both the colonizing aspects of infrastructure and the decolonizing potential of infrastructure and infrastructural thinking. The former is characterized by the Western-dominated logic of development. […] The latter, on the other hand, tries to connect us to the Earth, not as a resource to be consumed but as a ground to cohabit; to be protected, taken care of and helped to flourish.” (Kamari) It is now a site of damage, desire, fear and fecundity.

Why I look so close at language in the first place and bring to my thesis about diving writings of Haraway, Brathwaite, Butler or Weis is to remember its constant shifting quality and multiple ways it can be used (and misused)–language but also diving. As we are getting close to resurfacing from this state of submersion and this brief and sometimes painful event of a dive “might make possible the destruction of the more prolonged violence of language and of other dominant systems as they now exist.” (Gale 466)

In Bipolar Guide to Language Acquisition Orion Facey writes about the process of learning a language in which Orion reminds us that words do things more than they mean—something that children intuitively attempt at from the very young age (Facey 7). “The etymological roots of words can sometimes give us glimpses of the workings of dark grammar , especially when their origins seem to contradict their current usages […]. The slippages between the intentions behind the words our ancestors forged and the real trajectories of them point towards magical demons lurking behind the shadows.” (Facey 10) Below we can read an excerpt from Facey’s text:

The acquisition of a new language can be traumatic because the knowledge gained will illuminate parts of the dark grammar of the mother language.

The native speaker feels betrayed by their mother language, which is not entirely an unfounded suspicion.

The mother language had to lie to the native speaker, in order to hoodwink her into believing that the world of speech is more potent than the world of unspeech.

When she speaks in the new language, she can only speak monstrously, because she speaks from the void of the dark.

She illuminates the darkness that the listener has yet to discover. The listener is either appalled or aroused; in either case, she can only see a monster.

The more time a spellcaster spends in the darkness, the more she becomes attuned to magical energies.

She begins to make sense of monstrous forms, and their monstrosity becomes more and more symbolic in nature.

If she is able to return to the light, what she found within the dark is hers to keep. But what is found within the dark cannot be expressed with words.

THE DARK IS THE REASON WHY WORDS WILL ALWAYS BE INSUFFICIENT.

(Facey 11-12)

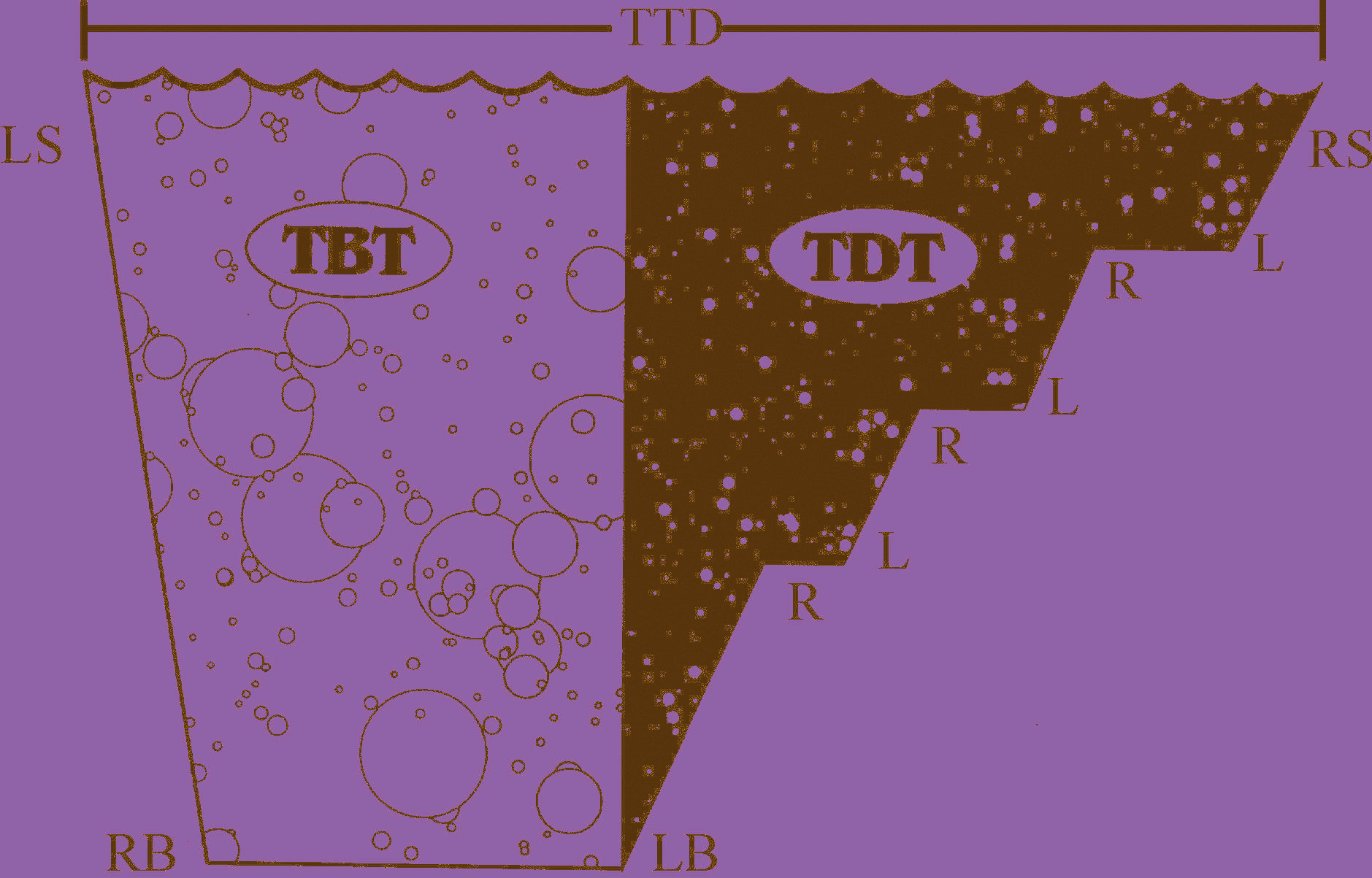

Re-surfacing

Graphic view of a dive. TTD - Total Time of Dive, LS - Left Surface, RB - Reached Bottom, LB - Left Bottom, R - Reached a decompression stop, L - Left a decompression stop, RS - Reached Surface, TBT - Total Bottom Time, TDT - Total Decompression Time

Re-surfacing

“Maybe it has to do with the humility of knowing that while we navigate the predictable there are phenomena old and ongoing that we’ve never even heard about, waiting for us to remember. What I know is I am proud of you, for the depth of work you are doing, for the layers you are uncovering, for the changes you made when you learned that what you thought was rock bottom was just a reflection of a sound you were making called need. For the thickness of your life and who it feeds. For the way you always teach me something new. Generous with all my layered needs.” Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals

Re-surfacing takes place at the end of the dive. The moment you signal to your partner that you will be resurfacing you give each other a sign of ‘thumbs up’. Underwater, this signal doesn’t mean “everything’s fine” or “well done”, what we might be used to. It might get misinterpreted by novice divers with gratifying that the dive is accomplished or finished, while that’s probably the most fragile moment of the whole dive. Not only is the diving body is weakened, but it’s also already more relaxed in the watery environment, accustomed to new sensorium (possessed new knowledge) and attuned to the environment, and with that language the body is able to navigate in it beyond its first sensations. “This is how this environment treats me and this is through this treatment that I recognize it.” (Weil 11) It’s probably here where all the former actions are manifested and compressed the most and need to be considered while attempting to leave the body in which you are submerged. The time and depth is crucial to decide how much time you need to attune yourself to the conditions of many levels.

The beginning of resurfacing, after both-side agreement, entails switching back to vertical position and looking up and listening, whether you hear any noise coming from the surface or there is anything that you might have to be careful not to get in contact with. That’s probably the first step to re-approach the environment of the land-based landscape. However, that environment, familiar to the body prior to the dive, isn’t sustainable for the submerged body yet. Being at the water depths involves breathing pressurized air. When ascending, the gases, such as nitrogen, need time to diffuse out slowly. Especially at the body’s limits.

With a too-sudden, non-suspended ascent the human body gets exposed to a rapid decrease in pressure that surrounds it which might result in decompression sickness.

At that moment, they acknowledge the responsibility of the action like submerging and reach a state of deeper understanding of the position you are taking–the position in which your body might easily find itself back in its originally comfortable environment unequipped to survive. The weight of transformation, both of the subject and perception, can be measured in the body’s buoyancy between resistance and receptivity. In this case, reemerging is an exercise that creates a space for negotiation between at least two environments that are mediated by a body in a movement—one being brought to the surface from the depth (resources); the other that sustains human and non-human agents’ life on certain depths; the diver’s body, in such case, is a go-between of this exchange.

The body becomes an active space for negotiation between two other subjects. The newly unfolded terrain of bodily capabilities and function might bring a new meaning to what has been dimmed forgotten (amniotic fluid), neglected in our bodies (disappearance), limited, or restrained by certain conditions of the environment.

We can attribute to a diver a role of a translator. There are two reasons that can justify that statement. One, the diver mediates the conditions across different levels and contexts, just as the translator who exercises ways of naming and seeing the world in two languages. Two: when approaching the surface, the diver starts reflecting and translating the experience into something that they will etch into their body as a memory–an embodiment of a certain apprehension.

In the essay “I’m Going to Describe a Ritual” Beatriz Santiago Muñoz unpacks possibilities and positions for meeting in a time and space of exception in which attention and perception are transformed. A common threat of practices described by Muñoz is that they seem to be degraded as minor and superficial, without depth. One story we can read is an interview with a writer and translator from Haiti Guy Regis Junior who’s undertaken a process of translating Proust’s In Search of Lost Time from French to Kreyol. How the activity of translating is a state of immersion manifests itself in Regis’ words about his process of translation.

I kept reading [Proust], as everyone does, both frantically, and driven by need for deep meditation. This great torrent in such deeply personal language – I wanted to express it, to interpret it myself. In other terms, translating is

reproducing, interpreting. That desire was enough, and I got to work – like a child, mimicking, interpreting this music in my own way, with my own instrument, my own language. Translating is entirely egotistical and at the same time

sacrificial. We translate out of the desire to deeply read a text. Everything starts there; language comes after.

(Santiago Muñoz)

Maybe the most striking part of this project is who makes, submits (becomes tetherless) and observes in depth is able to open other positions and relations between subjects. Guy Regis Junior’s project becomes even more relevant when we read that “Kreyol is an oral language; French is the language of literary instruction in Haiti. The translation of Proust to French is not a necessity, there are not thousands, not even hundreds of readers waiting to read Proust in Kreyol.” (Santiago Muñoz)

We can remember how the diver’s body becomes a site of very sensitive yet deeply transformative states that involve mediation of subjects/bodies belonging to different depths to bring a newly discovered meanings back to the surface.

The ending of Butler’s Speech Sounds for Nikita Gale suggests some “vague return to normalcy” when the main character Rye encounters two young children who seem to retain their ability to communicate, which for her means she too can speak and understand language. The discovery is in fact “an exercise in perception”, as that might suggest that it was otherwise all along–the ability was there–rather she had no one to listen to.

Bibliography

Facey, Orion. “Dark Grammar.” A Bipolar Guide to Language Acquisition, Self-published, 2021, pp. 9–12.

Gale, Nikita. “After Words: On Octavia Butler’s ‘Speech Sounds.’” Resonance, vol. 1, no. 4, 2020, pp. 462–66. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1525/res.2020.1.4.462.

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline, and Adrienne Maree Brown. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (Emergent Strategy). EPub ed., AK Press, 2020.

Gibb, Natalie. “The Most Common Scuba Diving Injury and How to Treat It.” LiveAbout, LiveAbout, 24 May 2019, https://www.liveabout.com/ear-barotrauma-most-common-scuba-injury-2963045.

Haraway, Donna, and Cary Wolfe. Manifestly Haraway (Volume 37) (Posthumanities). 1st ed., Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Harper, Douglas R. “Etymonline - Online Etymology Dictionary.” Etymology Dictionary: Definition, Meaning and Word Origins, 1960, https://www.etymonline.com/.

Hessler, Stefanie. Tidalectics: Imagining an Oceanic Worldview through Art and Science, TBA21-Academy, London, 2018, p. 31.

Lewis, Sophie. “Amniotechnics.” The New Inquiry, 31 Dec. 2017, thenewinquiry.com/amniotechnics.

Merchant, Stephanie. “Negotiating Underwater Space: The Sensorium, the Body and the Practice of Scuba-Diving.” Tourist Studies, vol. 11, no. 3, 2011, pp. 215–34. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797611432040.

Mohaghegh, Jason Bahbak. “Dinomania (Dizziness, Whirlpools).” Omnicide Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium, Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2019, pp. 245–75.

Neimanis, Astrida. “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water.” Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, edited by Henriette Gunkel et al., New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 96–115.

“Revolution and Destituent Power.” The Anarchist Library, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/anonymous-revolution-destituent-power. Accessed 5 Apr. 2022.

Rankine, Claudia. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric. Illustrated, Graywolf Press, 2004.

Santiago Muñoz, Beatriz. “ScrollDiving - Release I.” TLTRPreß, scrolldiving.tltr.biz. Accessed 22 Feb. 2022.

Weil, Simone, and Chris Fleming. “Essay on the Notion of Reading.” The Journal of Continental Philosophy, vol. 1, no. 1, 2020, pp. 9–15. Crossref, .