abstract

Neoliberalism, the socio-economic model of the present constitutes unsustainable standards of cognitive work. Precarization is spreading and the way we work is demanding ever more flexibility and adaptability to be fit in the game of free-market economy. Foucauldian biopower transcended the physicality of the ‘docile body’ when production labor was superseded by cognitive capitalism. ‘We [no longer] deem ourselves subjugated subjects, but rather projects: always refashioning and reinventing ourselves.’– writes Byung Chul Han in Psychopolitics. Liberation from external domination and the elimination of master figures produces the illusion of freedom, but in reality, new instrumental tools of power colonised the psyche. Now we are all carrying an internal labor camp within ourselves, wherein master and slave are fully integrated and Arbeit macht night frei – Labour does not set (us) free – but brings forth the totalisation of labor, generating psychopathologies such as burn out syndrome, attention deficiency, and depression. Therefore we have entered the era of neuropolitics, which is a novel technology of governing that invades the synaptic network of the brain. It is dominated by the discourse on neuroplasticity, the capacity that allow the brain to mold, (re)generate, and adapt itself structurally in its functioning. Claiming the brain as a highly under-utilized organ and describing its cognitive potentiality as limitless. I will investigate how the ingestion of neurochemicals can account for the stability of the neoliberal working conditions and the optional functioning of those with a neurochemical deficiency, a condition that results from the imperative to achieve without limits.

introduction

Myth does not deny thing, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but of a statement of fact. ― Roland Barthes, Mythologies

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes is analyzing how specific cultural objects have become the carrier of social value systems of modern society. He developed his notion of ‘myths’ relying on semiotics, the study of signs, inventing a model that constructs these modern myths. The model distinguishes two levels of signification: on the first level, we find the “language-object” operating, and beyond there is a second-order “metalanguage”, transmitting the myth.

In the era of neuropolitics, psychopharmaceuticals are signifying the emergence of the neuronal subject. This new mode of thought implies that ‘optimal’ cerebral functioning is indispensable in relation to performing under neoliberal

pressures of productivity and constant adaptability. On the meta-level, the ‘neuronal form of political and social functioning’ signifies the ongoing normalization of routine modulation and enhancement of mental functions by neurochemical

control, employed to harness market value.

How and when does the brain become the target of governing? What socio-political and economic conditions are playing a crucial role in this neuronal transformation? Perhaps, the most urgent question at stake is: what does the future hold for us when novel kinds of 'cerebral knowledge' and technologies are imposing new ways of being governed and how we govern ourselves? In the following, I am to investigate all of the above mentioned, departing from the underlying historical context that serves as the foundation of my hypothesis – the birth of biopower, a term originally coined by Michel Foucault in 1977.

Biopolitics

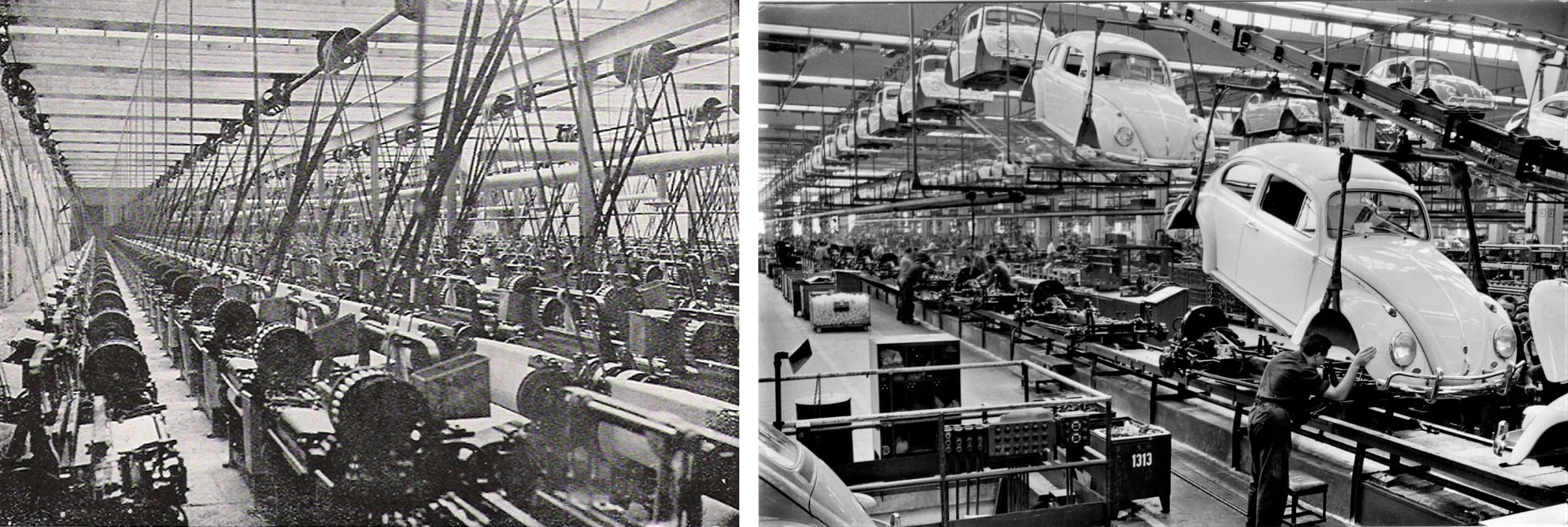

The advent of the steam machine – invented in 1764 by James Watt – triggered the Industrial Revolution. A manifold of industrial machinery started to appear in production, aiding the factory worker. This phenomenon fundamentally altered the structure of society, igniting the transformation of an agricultural to an industrial one. The birth of a new economic formulation, capitalism is to be dated roughly the same time. Simultaneously, ‘the West has undergone a very profound transformation of [the] mechanics of power’ - writes Michel Foucault in The History of Sexuality.

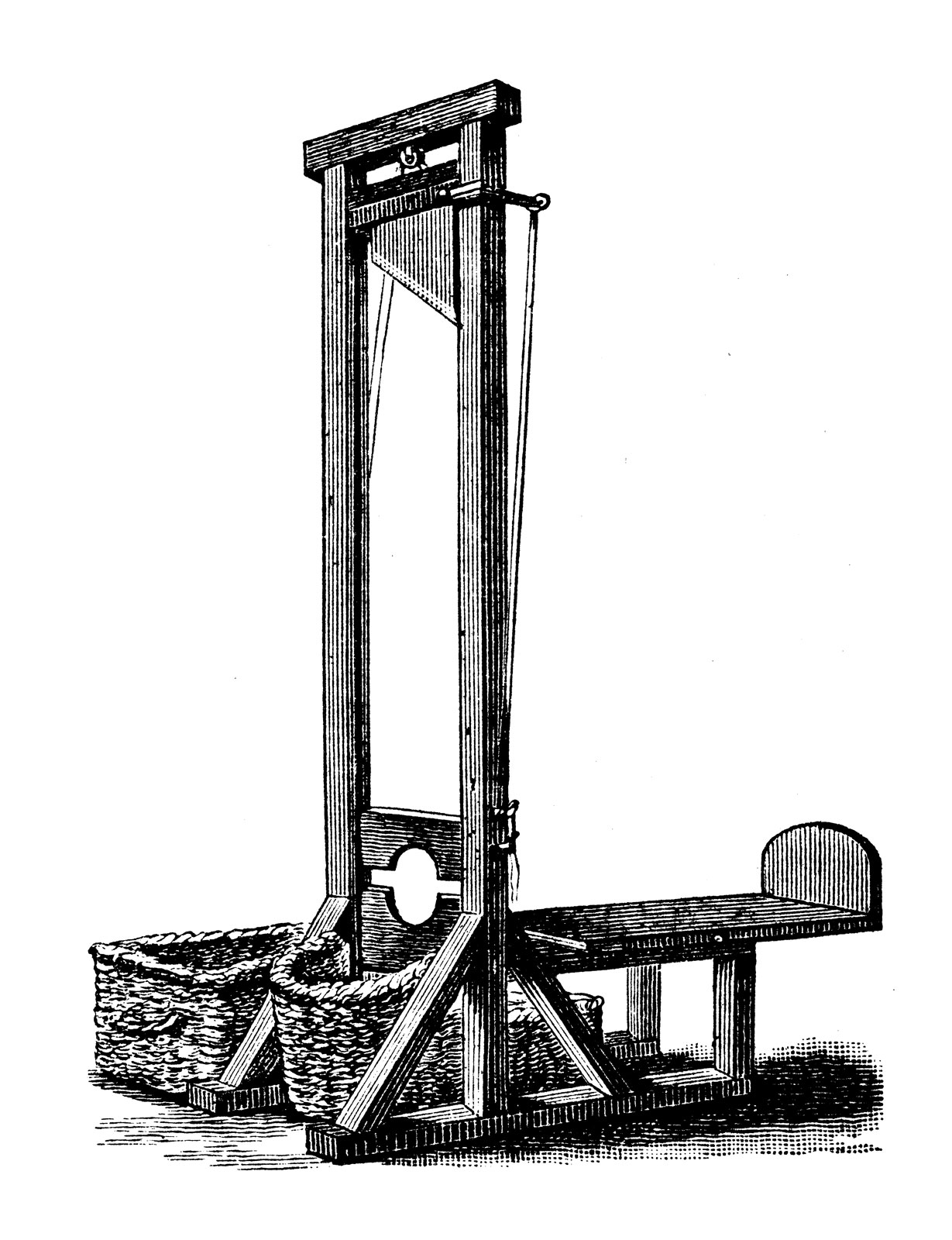

Preceding the Industrial Revolution, the sovereign exercised absolute power over its subjects. This power of the sovereign was operating on the framework of necropolitics, a term coined by Achille Mbembe, where the practice of torture and execution was serving as a public spectacle. Foucault claims – it operates mainly by means of deduction and is characterized by the right of death and power over life.

Nevertheless, necropolitics was not a sustainable form of subjectivation in terms of the capitalist economic model. The severe mutilation of bodies as a form of penalty disables and hinders the human subject from working, thus, becoming impotent for value creation. Sovereign power needed a shift towards promoting the wellbeing of its subjects, by ‘making them grow, and ordering them, rather than one dedicated to impeding them, making them submit, or destroying them’ . This marks the origin of biopolitics, an imperative feature of capitalism, which ‘would not have been possible without the controlled insertion of bodies into the machinery of production and the adjustment of the phenomena of population to economic processes.’

The objective of biopolitics is stretching beyond the preservation of life, and it is exercising control on birth and mortality rates, life expectancy, or longevity. In fact, it is merely a single instrumental tool that asserts power within the framework of what Foucault calls, the disciplinary society. According to the French philosopher, governing industrialized societies are happening by the so-called disciplines: ’… in a system like this, we are never dealing with a mass...we are only ever dealing with individuals.’

In sovereignty, each and everyone, as a collective social body is obliged both to author the power of the sovereign and obey the social contract at all times. Whereas, the disciplinary society fragments and redistributes power through extensive surveillance on individual human activities. It brings about the establishment of asymmetric power relations between those who are being surveilled and the executioners of such surveillance. As a result, these particular mechanics enhance utilization as they reciprocate increased docility.

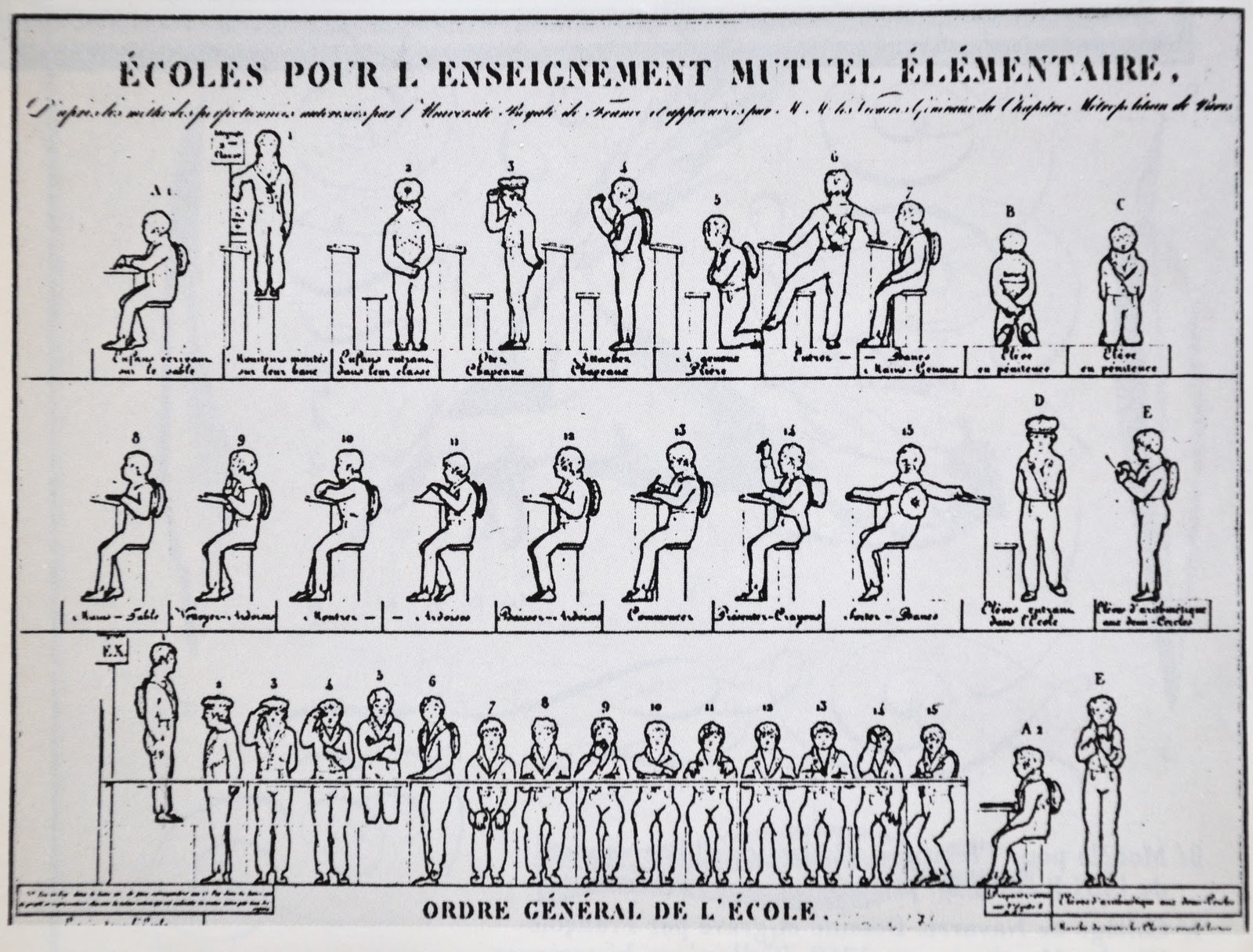

The distribution of power can only be operating efficiently as long there is a cellular division of space. The art of distributions, establishes individualism first by an enclosure of a particular space through the construction of walls and gates, like in the case of factories or barracks. Beyond the walls of these spaces, further principles are operating to ensure maximum control. Partitioning divides the given space into units, providing each individual with his designated place.

Its aim was to establish presences and absences, to know where and how to locate individuals, to set up useful communications, to interrupt others, to be able at each moment to supervise the conduct of each individual, to assess it, to judge it, to calculate its qualities or merits. It was a procedure, therefore, aimed at knowing, mastering and using. Discipline organizes an analytical space.’

In the case of factories, the central stage where production of capital happens, besides the division of workspace, the division of labor into smaller, specified, and monotonous operations simultaneously took place.

The last aspect to touch upon is the establishment of a ranking system. Foucault provides us the example of the seating arrangement in the classroom, where pupils are distributed according to age, grade, and behavior. He emphasizes, that this ranking system is never set in stone, but is fluidly altered after each examination. In the setting of the classroom or factory - where the level of productivity and output renders the ranking - such a system constitutes not only docility but the willingness to excel, habituating an inner drive striving to produce more, give more, be more.

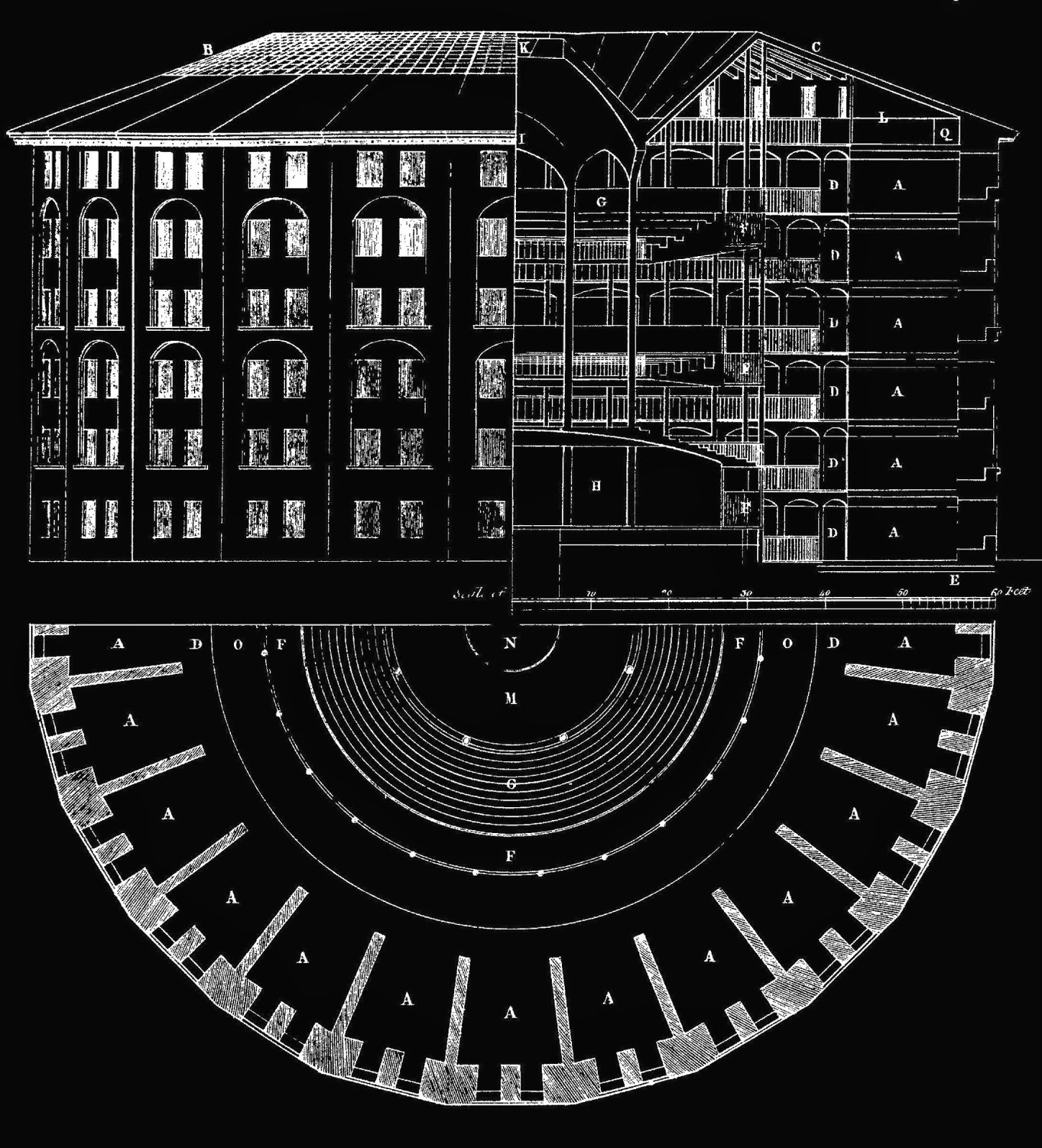

To sustain the mechanism of the disciplinary distribution of power, a ‘new principle of construction was to be employed in which persons of any description are to be kept under inspection’. Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon is often regarded only as a highly effective model of a prison, with an omnipresent observer in a tower encircled with a peripheral building, divided into equal units of space for the observed. However, both Bentham and Foucault specifies that the blueprint of a Panopticon is rather an architectural framework, which can serve any institution. Applicable to all facets of social institutions, be that a brothel, a classroom, a factory, or an asylum, it provides maximum force to whom, who directs power. While the physical element of visibility (of the observed) / invisibility (of the observer) produces biopower imposed on the bodies it encapsulates, it is also an attempt to obtain power over the mind. It activates a state of alert consciousness (Am I being watched?), which ‘assures self-regulation of the observed, rendering the automatic functioning of power’.

To finalize our depiction of disciplinary power, we have to look at the instrumental power of normativity. It is not enough to optimize, distribute and observe the objects, but it is crucial to demarcate boundaries between standards of expected behavior and forms of divergence, which altogether gives form to a socially constructed system of norms. Accordingly, it is to be judged whether a type of behavior is normative or deviant, which then brings about the righteousness of punitive action for the latter, and gives birth to a new discursive object: the figure of the abnormal. Throughout his body of work, Foucault introduces many faces of the abnormal; the criminal, who trespasses the conduct of legal law, the sexually deviant, who defies heteronormativity, or the madmen, who present psychopathologic symptoms.

We have seen how the absolute sovereign power, operated on deduction transformed into disciplinary power that targeted the body and maximized its functioning. Resulted by industrialization, human bodies were inserted into the orchestrated mechanics of production, which required the accommodation of new, meticulous manners of motion and conduction of oneself. Nevertheless, these novel techniques could only achieve the subjugation of bodies and not much of the mind. The architectural features of the Panopticon did attempt to penetrate the psyche, but the rhetorics of compulsion and prohibition fall short of achieving that. German philosopher, Byung-Chul Han claims, that in the society of the 21st-century, the negativity of the disciplinarian modal verb Should is superseded by the positivity of Can.The wake of Information Revolution outlines a utopian future, wherein humans set themselves free from their Rousseauian chains materializing upon the immaterial reality of fiber optics. However, gazing back in retrospect, we realize the utopia that sets the oppressed free remains utopia for the generations to follow.

Freedom will prove to have been merely an interlude. Freedom is felt when passing from one way of living to another – until this too turns out to be a form of coercion. Then, liberation gives way to renewed subjugation. Such is the destiny of the subject; literally, the ‘one who has been cast down'.

psychopolitics

The alienated worker is stripped from the autonomy of their own actions and is fully estranged from the ownership of value produced by their labor; therefore absolutely subjugated to those who own the means of production. Marx forecasted that such deprived human condition and the negative spiraling of surplus-value and labor cost will eventually result in the overthrow of capitalism by the revolution of the proletariat. On the contrary, production labor was instead substituted by the ever-increasing intellectual toil, and capitalism mutated into neoliberalism. Italian communist philosopher, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi in his paper Cognitarian Subjectivation, proclaims that the birth of cognitive capitalism roots in the refusal of alienation and exploitation, which instigates the necessity for developing innovative ways of production, fully replacing the worker with the machine. As he writes:

... The intellectualization of human activity is – from any perspective – a consequence of the workers’ insubordination and resistance to exploitation … and this has provoked the enhancement of the sphere of intellectual labor and cognitive activity linked to value production.

Intellectual labor fundamentally alters the instruments of labor: it supersedes the material nature of machinery and tools – owned by the bourgeoise – by the immaterial cognitive force possessed by every individual. Shifting from corporeal to non-physical, the locus of power surpasses the limbs and colonizes the psychic force of men. ‘We [no longer] deem ourselves subjugated subjects, but rather projects: always refashioning and reinventing ourselves.’ – writes Byung Chul Han in Psychopolitics. His philosophical work concerns the underlying precarious conditions of society encountered in the rapidly altering and technologically-driven post-Fordist state. He claims that subjectivation finds expression both in negative and positive forms – the latter is considered the main driving force in neoliberalism. The disciplinarian Should is as coercive as the unlimited Can, which produces the so-called achievement society that is governed through psychopolitics.

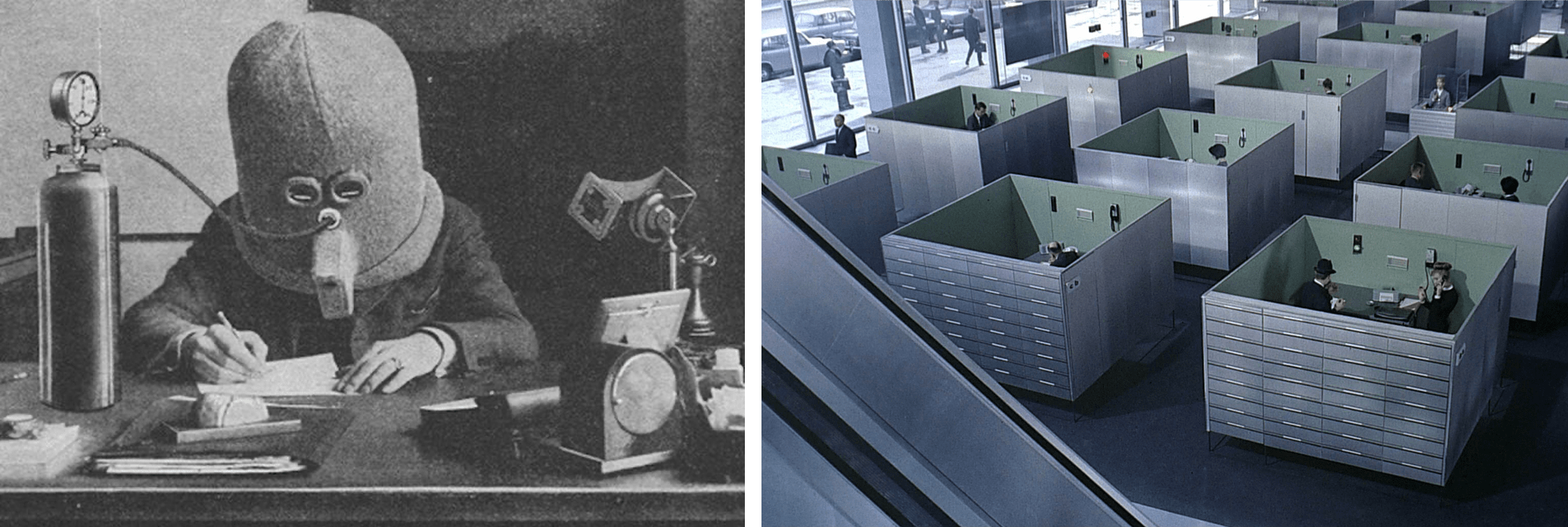

Referring back to the arts of distribution, the walls enclosing the Foucauldian subjects have perished and were replaced by innovative communal spaces advertised as delivering the perfect aesthetics and atmosphere for productive working. The reason why such a considerable amount of change took place lies in the inherent difference of the instrumental power psychopolitics applies to the working body. Although the substantial changes in the workspace stripped away the visible resemblance to the panoptic architecture, in the end, it reinforces a vast more efficient kind of subjectivation. Goals, projects, initiatives of the achievement-subject retrieved the alienation of labor and the ‘I is now subjugating itself to internal limitations and self-constrains, which are taking the form of compulsive achievement and optimization’ . As follows, Han unveils the genuine face of today's freedom, claiming that ‘in so far [the achievement-subject] willingly exploits itself without a master it is an absolute slave’ . Liberation from external domination eliminates master figures and constructs an internal labor camp within every individual. In this utter state of solitude, wherein master and slave are fully assimilated, Arbeit macht nicht frei (Labour does not set (us) free), but brings forth the totalisation of labor. There is no longer a need for enclosure and partitioning because we are locked in our personal Panopticon while sipping oat milk cappuccino and wearing padded headphones to cancel out distractive noises.

Right: Infamous office set from Jacques Tati's Playtime, anticipated the dominance of office cubicle arrangements by some 20 years.

As cognitive capitalism altered the means of production, it also inherently eradicated the class struggle. ‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles’ – so begins the Communist Manifesto, the political pamphlet of Marx and Engels. They claim, that human societies have always been divided into oppressors and the oppressed, and eventually all these societies were overthrown by revolutionary reconstitutions to eliminate such differentiation. That comes from the potentiality that individuals who are suffering under the same conditions could join forces by the means of their shared antagonism. But how could the auto-exploiting achievement-subjects find any common denominator for political action, when the master is locked in their own minds?

Thus, the sense of belonging to a common ‘us’ is wearing thinner by the day, which greatly accounts for the stability of neoliberalism. Furthermore, it is crucial to touch upon another grounding pillar, that further deepens social alienation; the omnipresence of precarity. While previously, precarization meant something foreign to the developed western society, occurring only in the far distances of the ‘Global South’, it relocated from the socio-economic peripheries to constitute a new form of government.

Political theorist, Isabell Lorey in her book State of Insecurity, connects the notion of precarization with modern governmentality, arguing that the preferred way of governing today is realised ‘through regulating the minimum of assurance, while simultaneously inscribing instability and social insecurity’ . Among others, she accounts precarity for the erosion of a possible collective organization, as it facilitates the rise of short-term, flexible, and insecure employment conditions. She claims the precarious tend to be effectively isolated and individualized caused by the dispersion both in relation to production and the diverse modes of production, thus rendering a neo-marxist revolution impossible. This is all due to the ‘neoliberal demolition and restructuring of collective security systems’, which is continuously enforcing increased pressure on the neoliberal subject to self-govern.

Exploitation and the alienation of the proletariat, according to Marx, were the seeds carried within capitalism that would eventually bring its own destruction. In stark contrast, workers’ disobedience did not deliver the desired downfall but rather fuelled elementary reinvention. Change in rhetorics mastered the voluntary subordination of the cognitariat: obscuring exploitation to be perceived exploitative. Whereas, precarity has generated more insecure and unpredictable labor conditions that are in consequence, demanding the worker to be ever more flexible and adaptive. The false prophecy of excessive positivity is there to promote the elimination of weaknesses and faulty characteristics to enhance efficiency and performance, – just to regulate one’s own precariousness. At last, disciplinary inhibitions fell, but only to be replaced by inner inhibitions to struggle against. Under these circumstances does the neoliberal subject of today crumble, falling into the captivity of no longer able to be able [nicht mehr können kann]. Neurological illnesses such as depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder, and burnout syndrome mark the landscape of pathology at the beginning of the 21st century.

The depressed individual, caught in a moment with no tomorrow, is left without drive, bogged down in a “nothing is possible.” Tired and empty, restless and violent – in short, nervous – we feel the weight of our individual sovereignty. The decisive displacement of the difficult task of appearing healthy, is, according to Freud, the price the civilized person must pay.

neuropolitics

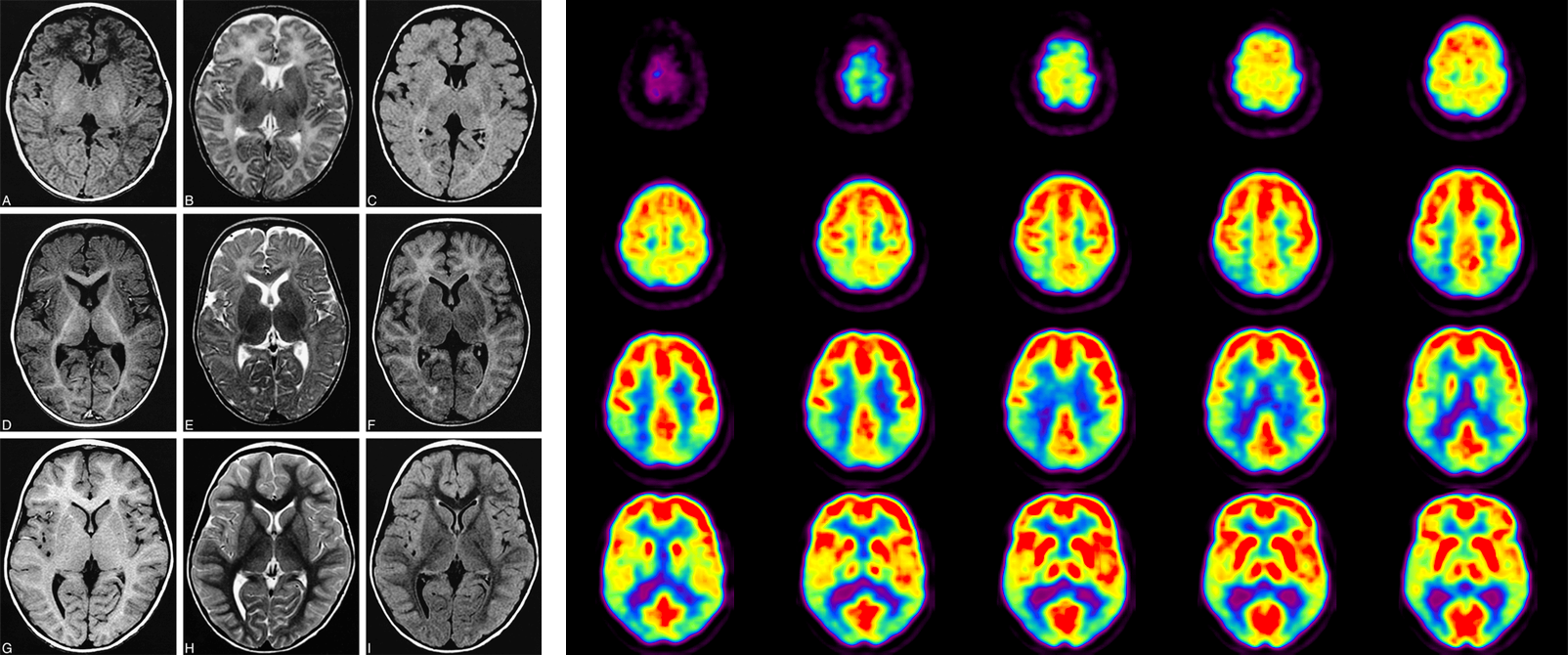

Since the beginning of its existence, Homo Sapiens have always been inventing new technologies, that in return keep inventing a new type of human, being an active agent in shaping the perception of who we are and what makes us human. This type of power-knowledge is fully intertwined with the social, economic, and political terrains and continuously alters the particular ways of how we are being governed and how we govern ourselves too. Accelerating technological changes, that are originating from the arms and space race dominating the Cold War period, has led scientists to discover new ways of mapping the complexities of the human body. Refined digital image processing, which NASA developed for the Apollo Lunar Landing, later have found a broad array of other applications, especially in diagnostic purposes for medicine. As a result, machines like the MRI, CT, and PETScan have become one of the most powerful clinical tools that brought medicine to the modern era. Essentially, these machines enabled medical professionals to gaze at the human body through a radically new lens, and that is significantly altered how we see ourselves. Nicolas Rose in The Politics of Life itself claims, that we still tend to think of ourselves on a corporal, tangible, ‘molar’ level, however, contemporary biomedical practices are rather targeting us on a molecular level.

... life is now understood, and acted upon, at the molecular level, in terms of the functional properties of coding sequences of nucleotide bases and their variations, the molecular mechanisms that regulate expression and transcription, the link between the functional properties of proteins and their molecular topography, the formation of particular intracellular elements—ion channels, enzyme activities, transporter genes, membrane potentials—with their particular mechanical and biological properties.

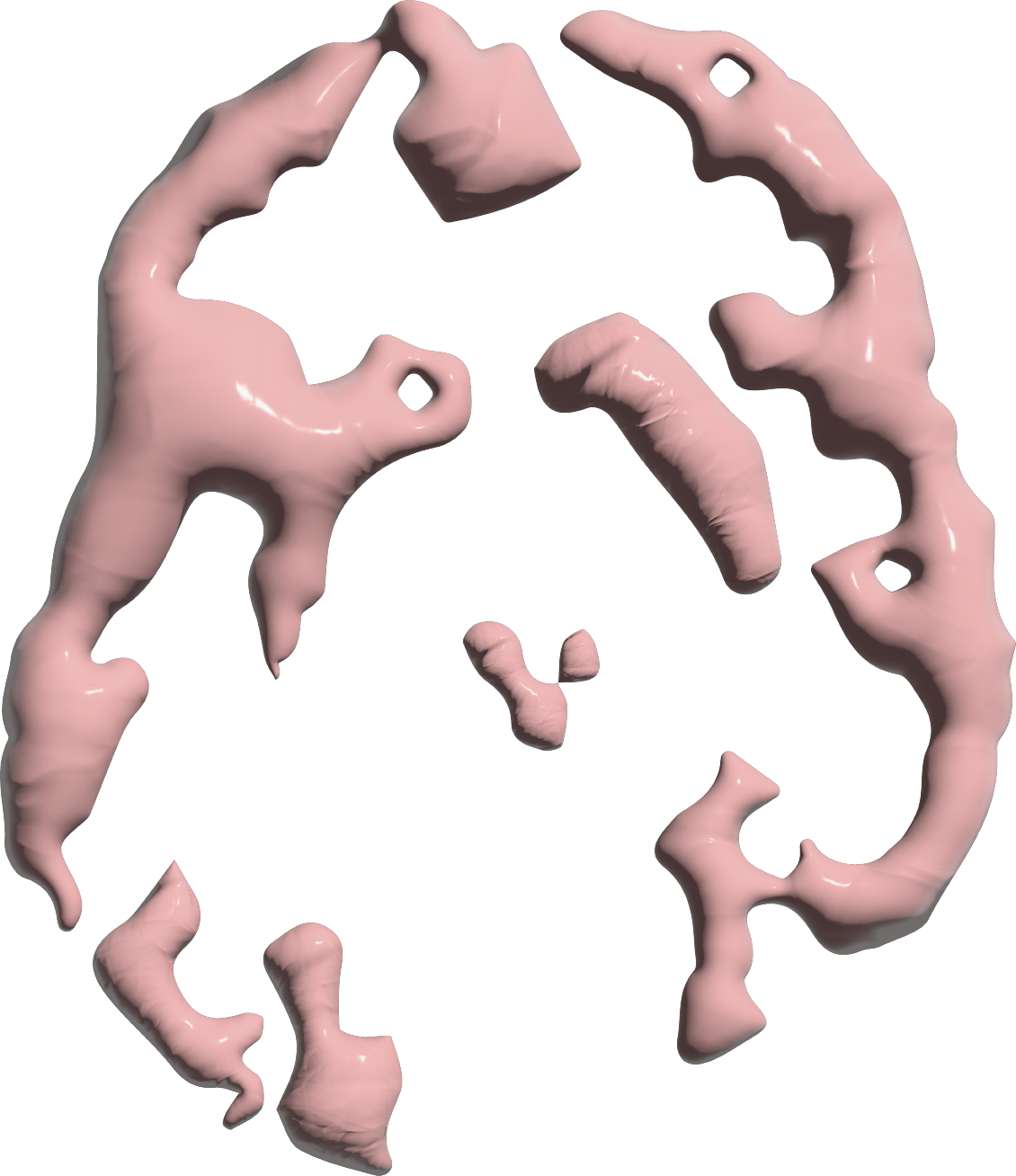

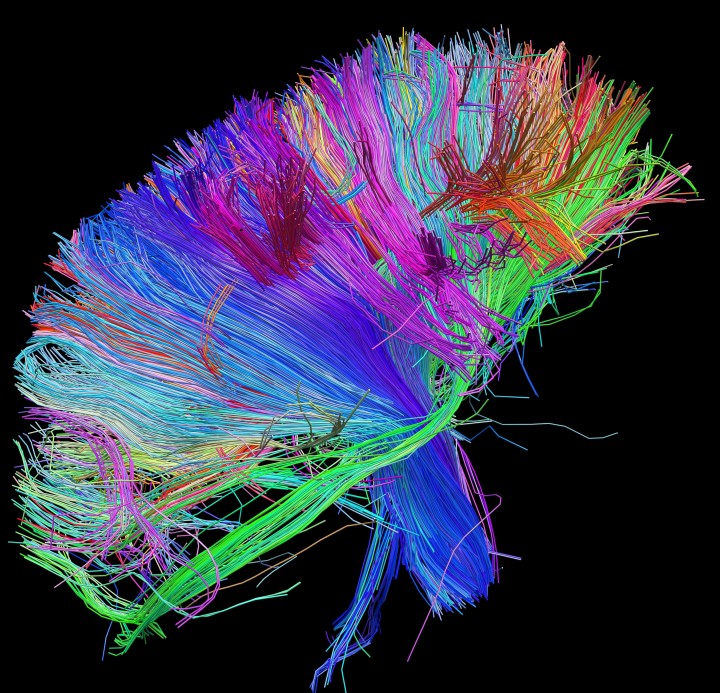

Like in the case of The Human Genome Project, which was an international effort to map out the human DNA in its full length, making it accessible for further biological studies, modern technologies of gene manipulation, such as CRISP-R emerged soon after, raising many ethical questions about its possible applications. A vast amount of neuro - and computer scientists today are working towards a new paradigm for understanding the brain, by decoding the structural wireframe of the human brain. The incentive of such a large-scale project is none other than ’to advance neuroscience and medicine and to create brain-inspired information technology’. Therefore I claim, that the emergence of interest shown towards the brain and its functioning shapes how we regard ourselves and how our neural networks are being targeted by novel techniques of governing power.

The reason why neuropolitics surpasses the efficiency of psychopolitics is that the former offers both the continuation of subjectivation and the solution to minimize the collateral damage, that the latter has brought about. Furthermore, while biopower earlier could only impose its effects on bodies, and psychopower could only capture the psychic abilities, neuropolitics seeks to seize control both on the somatic and psychic level on its human subject. Aforementioned Nicolas Rose, who worked extensively on exploring the history and sociology of psychiatry and the social implications of recent developments in psychopharmacology, distinguishes several ‘pathways along which neuroscience becomes entangled with the government of the living’. In the following, I am to investigate how neuroplasticity and psychopharmacology embody ways of governing today.

The scientific discovery of brain plasticity or neuroplasticity hugely affected and fundamentally changed the way neuroscience, and later society and culture regarded the brain. The term ‘neuroplasticity’ was first coined by Jerzy Konorski, a polish neuroscientist in 1948, and is referring to the capacity allowing the brain to mold, (re)generate, and adapt itself structurally in its functioning. Preceding, in the work of Santiago Ramon y Cajal we can already find the hypothesis proposing the possibility of neuronal growth and altering in the adult brain. He writes in his anecdotal guide Advice for a Young investigator published in 1897 that ‘any man could, if he were so inclined, be the sculptor of his own brain’.

Nevertheless, brain plasticity proves to only emerge and taken serious in the realm of modern neuroscience from the 1980s – claims Victoria Pitts-Taylor in her paper titled The plastic brain. She introduces how plasticity refers to multiple processes of brain functioning, like the ability of neurogenesis (the production of new neurons ), synaptogenesis ( the establishment of new synaptic connections between neurons), and synaptic modulation ( strengthening or weakening of the existing connections). Later, she outlines the problematics on neuroplasticity that is the subject matter of this paper: plasticity is deployed to encourage us to see ourselves as neuronal subjects, … [that] firmly situates the subject in a normative, neoliberal ethic of personal self-care and responsibility linked to modifying the body.

[..] Plasticity directly contradicts rigidity. It is its exact antonym. In ordinary speech, it designates suppleness, a faculty for adaptation, the ability to evolve. According to its etymology - from the Greek plassein, to mold - the word plasticity has two basic senses: it means at once the capacity to receive form (clay is called "plastic," for example) and the capacity to give form (as in the plastic arts or in plastic surgery) … But it must be remarked that plasticity is also the capacity to annihilate the very form it is able to receive or create. We should not forget that plastique, from which we get the words plastiquage and plastiquer, is an explosive substance made of nitroglycerine and nitrocellulose, capable of causing violent explosions. We thus note that plasticity is situated between two extremes: “on the one side the sensible image of taking form (sculpture or plastic objects), and on the other side that of the annihilation of all form (explosion).”

This duality thus implies from one side, normative standards impose distinct castings for us to mold into, but from the other, it might be the very agent in deforming, refusing to take any cast at all. As much as I am very drawn to unfold the possibilities in the latter, I am to argue in the following how neuroplasticity is framed to support neoliberal economic goals. The first aspect that needs addressing is how the discourse on neuroplasticity established the brain to be conceived as this highly flexible and adaptable organ. Based on her content analysis, of 250 print media accounts, Victoria Pitts-Taylor claims the brain’s capacity is often articulated as highly underutilized and its potential presented untapped. It is strongly advocated to become fully aware of this condition and initiate the adoption of certain practices, that are believed to enhance cerebral connections.

Neoliberalism operates in a highly comparable model, as social theorist Pierre Bourdieu calls it “the absolute reign of flexibility”. Subjects of the neoliberal economy are driven to be ever more flexible and adaptive to keep up with the continuous precarization of working conditions. In order for neoliberalism to thrive, its economic processes require perpetual growth, which today is mainly achieved through the engineering, modulating, and harvesting of value from the vital capacities of its subjects. To avoid atrophy, economic engines must move forward, just as the brain requires master tasks, to keep neuronal pathways strong and interconnected. As a contemporary technology of the self, brain plasticity is shifting a significant amount of responsibility on the individual to self-regulate, and take risk-avoiding preventive measures. The very problem at stake nonetheless is, that the (unsustainable) socio-economic regime of neoliberalism is the leading factor in the spiking rise of psychopathologies.

How many workers of the new economy survive without Prozac, without Zoloft or without cocaine? The habituation to psychotropic substances, those that can be bought in a pharmacy and those that can be bought on the black market, is a structural element of the psychopathogenic economy.

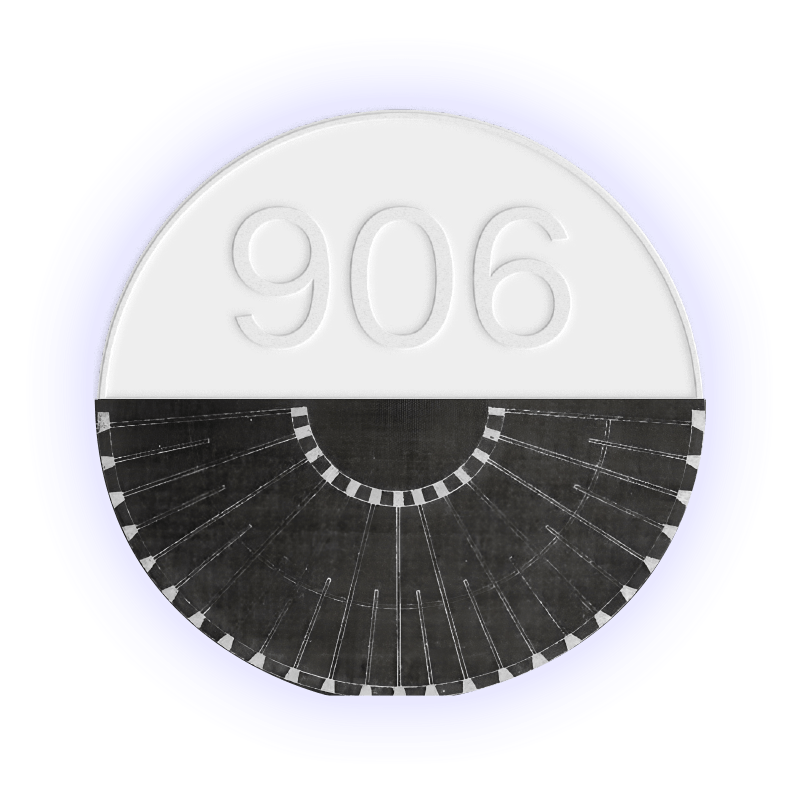

The last aspect left undiscovered is delving into how neuropolitics operates via chemical control being imposed on the neoliberal subject, therefore, becoming the new normal. On March 26, 1990, Newsweek presented ‘A Breakthrough Drug for Depression’ on their cover, featuring a blown-up illustration of a pill, that by today sounds all too familiar to everyone: Prozac. The green-and-white pill containing 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride claimed to be a game-changer in treating melancholia and fundamentally changed how society regards the ‘dysfunction’ of the brain in the 21st century.

SSRIs, standing for serotonin reuptake inhibitors entered the public knowledge to be a highly efficient new compound, as they would precisely target the neurochemical anomaly on the cellular level: the low serotonin levels found in the synapses. Drug advertising and a vast amount of publications praised Prozac and its doppelgängers, like Zoloft and Lexapro to be some wonder-drug, that would lift the unbearable weariness and paralysis from one’s shoulder, and help re-vitalizing the individual, while also inherently contributing to how clinical depression is framed as a one-dimensional dysfunction of a monoamine transmitter. Despite the fact, that the very functioning of the SSRI’s has been brought into question not long after their initial introduction to the market, and the scientific community regards their working mechanism solely based on a hypothesis, the number of dispensed antidepressant medicine users in the Netherlands amounted to nearly 1.04 million in 2020.

What does it mean for modern society, that even though SSRIs are proven to be as ineffective as given placebos for the majority of those taking them, while often causing negative side effects and withdrawal symptoms, prescription, therefore consumption rates still continue to increase? It is inarguably evident, the accelerated use of psychopharmaceuticals is driven by the key values neoliberal political economy aims to serve. As neoliberalism eradicated the security of social welfare, and significantly reduced the role of non-market institutions, like trade unions, while pervasively promoting individualism and defining all human relations in terms of competition, the individual turns to the most evident solution, that requires a minimal amount of invested time and effort solving their problem.

Beyond the increasing amount of prescriptions, imposing to offer an answer to the increasing number of the population diagnosed with any kind of psychopathological disorder, the abuse of psychotropic substances to seek an advantage in cognitive performance and work productivity is on the rise too. The use of cognitive enhancement is multifaceted and multidimensional and has nevertheless raised countless ethical, societal, and medical concerns. I am to distinguish three different facets of these substances in use, differing in terms of origin, the active compound, target group, accessibility, and (il)legality.

Pharmaceutical psychostimulants, that are clinically approved treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy are among the scheduled substances according to the American Controlled Substances Act. Many active compounds, like amphetamine, ephedrine, methylphenidate, propylhexedrine, and modafinil, placed from Schedule VI to II, fall into this category. Although these compounds are dominantly found in prescribed medications, some of them occur in natural forms as well. Perhaps the most commonly known representative of this category is Adderall (amphetamine) and Ritalin (methylphenidate). While it is fundamental for optimal mental functioning in everyday life of those diagnosed with ADHD, it is rising popular among those without the disorder to stimulate cognitive performance. According to DEA Diversion Control report, the primary abusers are individuals younger than 25 years of age; who often obtain methylphenidate from a friend or classmate and use this drug as a study aid.

Nootropics or ‘smart drugs’ are another class of substances, that claim to boost brain performance. They are nonprescription ‘supplements’, often packaged and advertised boldly and expressive, and in their functioning described overly compelling. The active compounds found in nootropics are predominantly from natural origins, such as Lion’s Mane or Gingko Biloba, which altogether make the most attainable brain booster out there – however, its efficiency rate is highly questionable.

The last subcategory to mention is the use of illegal psychostimulants, like cocaine, methamphetamine, and khat, or psychoactive compounds like LSD, mescaline and psilocybin. Many of these make up the category “hard” drugs and are illegal to use in most countries, which makes them the least accessible, yet still possible to acquire via the black market. They are much more potent in their efficiency, but it comes with the price of elevated dangers for addiction. However, in recent years, a new strategic method of consumption of many aforementioned substances emerged among the forerunners of neuro-enhancers: microdosing. Microdosing is the practise that refers to precise dispensing of small amounts of a substance, that is unable to produce the full effect, yet brings forth positive mental changes. It is considered a highly experimental approach, which balances on the thin edge between what is considered legal and illegal. The practice of microdosing emerged from Silicon Valley, that in truth incubates neoliberalism at its very core.

conclusion

We started with necropolitics: the divine decision of the sovereign over life and death, which was fundamental to upkeep feudalism, turned immediately obsolete as the first steam engines of the Industrial Revolution were ignited. Biopolitics managed to insert a vast amount of bodies into the massive, mechanical apparatus of industrial machinery, however as soon as production labor is immaterialized, biopolitics renders rudimental and thus ineffective. Psychopolitical governing techniques finally accomplish to tap into the psychic force of men, that Foucault only could dream of, yet it proves to foster the very conditions that lead to its possible atrophy.

By and large, this paper could not truthfully encapsulate all aspects that play a role in such messy and intertwined relations between bodies, power, knowledge, labor, economy, ideology, alienation, precarity, productivity, not being able to be ableness, and psychopharmacology, that constructs neuropolitics, nevertheless it is an honest attempt to bring awareness to the subject matter. Only when we are in possession of understanding the conditions that are constantly shaping our very existence, will enable us to take the lead in searching for better future alternatives, that might truly set us free after all.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “The Crisis of Freedom.” Psychopolitics:Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY, 2017.

- Barthes, Roland, et al. Mythologies. Vintage, 2009.

- Malabou, Catherine. What Should We Do with Our Brain?, Fordham University Press, New York, 2008.

- Foucault, Michel. “Right of Death and Power over Life.” The History of Sexuality, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978.

- Foucault, Michel. “Right of Death and Power over Life.” The History of Sexuality, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978.

- Foucault, Michel. “Right of Death and Power over Life.” The History of Sexuality, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978.

- Foucault, Michel. “Right of Death and Power over Life.” The History of Sexuality, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978.

- Foucault, Michel. “Lecture 4: 28 November 1973.” Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1973-74, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, 2008.

- Foucault, Michel. “Docile Bodies” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York, 1995.

- Bentham, Jeremy, and Miran Božovič. “Panopticon Letters.” The Panopticon Writings, Verso, London, 2010.

- Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York, 1995.

- Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York, 1995.

- Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Vintage Books, New York, 1995.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “Beyond Disciplinary Society.” The Burnout Society, Stanford Briefs, Stanford, CA, 2015.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “The Crisis of Freedom.” Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY, 2017.

- Berardi, Franco “Bifo. “Cognitarian Subjectivation - Journal #20 November 2010 - e-Flux.” e, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/20/67633/cognitarian-subjectivation/.

- Berardi, Franco “Bifo. “Cognitarian Subjectivation - Journal #20 November 2010 - e-Flux.” e, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/20/67633/cognitarian-subjectivation/.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “The Crisis of Freedom.” Psychopolitics:Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY, 2017.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “The Crisis of Freedom.” Psychopolitics:Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY, 2017.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “The Crisis of Freedom.” Psychopolitics:Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, Verso Books, Brooklyn, NY, 2017.

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto, Penguin, London, 2002.

- Marx, Karl. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. Progress Publishers, 1982.

- Lorey, Isabell, et al. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Verso, 2015.

- Lorey, Isabell, et al. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Verso, 2015.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “Neuronal Power.” The Burnout Society, Stanford Briefs, Stanford, CA, 2015.

- Han, Byung-Chul. “Neuronal Power.” The Burnout Society, Stanford Briefs, Stanford, CA, 2015.

- Ehrenberg, Alain. The Weariness of the Self: Diagnosing the History of Depression in the Contemporary Age. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

- Rose, Nikolas S. Politics of Life Itself Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Rose, Nikolas S. Politics of Life Itself Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Human Brain Project, https://www.humanbrainproject.eu/en/.

- Rose, Nikolas, and Joelle Abi-Rached. “Governing through the Brain: Neuropolitics, Neuroscience and Subjectivity.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, vol. 32, no. 1, Berghahn Books, 2014, pp. 3–23, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43612892.

- Santiago, Ramón y Cajal. Advice for a Young Investigator. MIT Press, 1999.

- Pitts-Taylor, Victoria. “The Plastic Brain: Neoliberalism and the Neuronal Self.” Health, vol. 14, no. 6, Sage Publications, Ltd., 2010, pp. 635–52, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26650062.

- Pitts-Taylor, Victoria. “The Plastic Brain: Neoliberalism and the Neuronal Self.” Health, vol. 14, no. 6, Sage Publications, Ltd., 2010, pp. 635–52, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26650062.

- Malabou, Catherine. What Should We Do with Our Brain?, Fordham University Press, New York, 2008.

- Pitts-Taylor, Victoria. “The Plastic Brain: Neoliberalism and the Neuronal Self.” Health, vol. 14, no. 6, Sage Publications, Ltd., 2010, pp. 635–52, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26650062.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Richard Nice. Acts of Resistance: Against the New Myths of Our Time. Polity Press, 2004.

- Berardi, Franco. “What Does Cognitariat Mean? Work, Desire and Depression.” Cultural Studies Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 2013, pp. 57–63., https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v11i2.3656.

- Mikulic, Matej. “Users of Dispense Antidepressants Netherlands 2014-2020.” Statista, 2 July 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/718241/usage-of-dispensed-antidepressants-in-the-netherlands/.

- Methylphenidate (Trade Names: Ritalin- (Ir, LA, and SR ...https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/methylphenidate.pdf.