CHALGA

The Music in Bulgarian Life

Abstract

Chalga is a Bulgarian music genre, a mixture of Balkan rhythm and oriental embellishments. Being the most popular music genre in the country, it was intriguing what is it really and why the feelings towards it are so mixed. Where did it come from and where is it going?

Listening to songs and watching videos, reading academic papers on Balkan music and talking to various artists, academics and casual listeners, I noticed how well chalga represents the needs of Bulgarian society. In a humorous way, it reflects excessive wealth, enjoyment and eroticism that people crave but are ashamed to admit. Chalga ties into a much deeper problem of disturbed national identity, where it serves as a vent to release all that pressure.

Foreword

I don’t easily get offended but when I heard the term balkanisation, a derogatory geopolitical term for the process of fragmentation or division of a region or state into smaller regions or states that are often hostile or uncooperative with one another, I lost my temper. The Balkans (Fig.1) have had a turbulent history of conquest by the Romans, various nomadic tribes, the Ottoman Empire and they have always survived. What led to the assumption that they are more uncooperative with one another than other European nations? What is this cloak of dishonour covering the region? Undoubtedly, there is much to be proud of—but what is it? Food, dances, knowledge or music? All regions in the world can boast with something even if it seems strange or even disturbing to foreigners.

For me and many other Bulgarians this is chalga music, a popular upbeat music with oriental blemishes and provocative imagery and lyrics. There can’t be Bulgaria without chalga and vice versa. Despite the attraction to its rhythmical and joyful sounds, chalga is not openly accepted. ‘We are forced to listen to it’, ‘You just have no choice’ or ‘We have grown up with it, what do you expect?’ are some of the common arguments for listening to chalga. But when Dimityr Dimitrov, the owner of the biggest chalga production company Planeta Payner, applied for an EU subsidy worth millions of euros, he was publicly shamed.1 As if people feared chalga becoming bigger or, even worse, becoming popular in the West.

When I was a teenager in the early 2010s, some people expressed their hatred for chalga and stood to make chalga illegal for listening. I was into Black Sabbath and Guns n’ Roses and I did not listen to chalga but I was also indifferent to such strong emotions. In the Netherlands, however, chalga was like discovering the ‘fountain of youth’ for my homesick soul. At parties we were provoking our foreign friends by playing classic tracks that we would not play at home. I wondered what held me back all this time? How could there be so much reservation around one music genre? Tracing its history, I found out it offers much more than a few scandalous videos and provocative lyrics. It reveals a history of adaptation, infusion of cultures and rhythms, which served as a coping mechanism for the post-Soviet reality. For the last 30 years it has been an accurate reflection of Bulgarian society while staying the most popular music genre since its conception. Shows in the US, Canada, England or the Netherlands get many Bulgarians together and their hearts are stricken with loads of emotions of familiarity and saudade. Paradoxically, in Bulgaria most people are ashamed by it. They deny that chalga reflects their world so well, labelling it as ‘foreign and inauthentic’.

Overview of chalga

Chalga is the Bulgarian version of the Balkan folk music known as Turbo-folk in Serbia, Laiko in Greece, Manele in Romania or Tallava in Albania. Musically it strongly resembles oriental music due to asymmetrical rhythms and instruments like the accordion or violin. However the visual language rarely references directly anything related to Turkey or the Ottoman Empire, belly dancing being the exception. Chalga flourished in the 90s popularised almost completely by its video material. Much like MTV in the West, Bulgarian producers realised that music clips were essential to promote songs on cable TV, in clubs and cafes.2 The quality of those videos varied but it took a very short time for producers to excel3 in it going from ‘amateur one-camera shots to sophisticated professionalism.’ The production quality nowadays is relatively high and it is hard to distinguish from any Western production. Unless, of course, we look into the content of the videos.

There are several themes which reappear since the 90s, which serve as strong symbols of the Bulgarian needs and desires for opportunity and freedom. For 30 years of democracy materialistic needs haven’t been generally satisfied. Chalga is the music that gives a peek into a world of abundant riches, it provides joy and excitement and breaks the social reservations with loosely clothed men and women, exposing the innate sexual drive of everyone. Those themes are not unique, but perhaps chalga took them to another level.4 Being provocative, satirical and hyperbolical about every visual trope, producers market their content in almost every corner of the country and even beyond.

Inferiority Complex

In the beginning of the 20th century the Bulgarian writer Aleko Konstantinov tells the story of Bai Ganio who is a ‘typical Bulgarian character’. With his sharp trading mind and fabulously bushy moustache he departs to Vienna to explore the Western world, share Bulgarian culture and earn some money on the side by selling rose oil. Unfortunately, he exposes his Balkan manners a few times, such as shouting on the streets of Vienna or banging his chest, growling ‘Bulgar! Bulgar!’ to announce his home country. Bai Ganio is not a terrible man, but he is a collective character for all negative Bulgarian traits like profanity, egocentrism, hedonism and greed. He was created to remind the people that one should behave in a society with different ideals and culture and leave the ‘Orientalist thinking’ behind. Perhaps it worked all too well, because one is humiliated when accused of manifesting such traits, traits that chalga easily exemplifies.

Shame is very interesting as a psychological phenomenon because it needs an external viewer. In contrast to guilt that is internal and concerns the action, e.g. murder, that has been done, shame is pointed at the doer and their moral values, e.g. being disrespecful to war heroes. Nevertheless, there are actions that are classified as ‘bringing shame’. In his book5 Musical Concerns, Jerrold Levinson points out that ‘ashamed’ is one of them. Another one is ‘shameful’. A shameful musical taste is when you like music people generally find repulsive. Would the opposite be positive? Shameful → shameless? No, it is also a negative adjective. So it seems as soon as something is labeled as shameful it is hard to reverse it. Chalga music, in all its forms, has been criticised by people in the 19th, 20th and 21st century. Nevertheless, it did not stop developing, adapting, reflecting Bulgarian reality. And the arguments against it have always been the same: too vulgar, too erotic, too ‘foreign’.

But if chalga shows reality, how come it is so shameful? Reality cannot be repulsive, but the perception of it can be. ‘Chalga’ has come to be an adjective used to denote poor-quality variation of a thing: ‘chalga politicians’, ‘chalga historians’, ‘chalga culture’.6 And moreover, people talk about ‘spiritual emigration’ which is a result of ‘chalgization’ of the whole nation.7Thus, suggesting that one sole music genre is responsible for the harsh and unfair reality. So is Bulgaria chalgagized? National identity is a puzzling construct, because of two subjugations that lasted for centuries. The first by the Byzantine Empire for almost two centuries and the second by the Ottoman Empire for five centuries. The latter being so long, that almost assimilated the native culture and traditions. After the liberation in 1878, Bulgaria suddenly had to respond to Europe. At the time the ‘elite’ was already identifying with other cultures trying to reject everything Ottoman or traditionally Bulgarian.8 In the influential novel Криворазбраната цивилизация (The Phoney Civilization) Dobri Voynikov humours a lifestyle, where traditional values are left behind as old-fashioned, while blindly copying everything French and Austrian. In a way this is a reaction to the simplicity and coarseness of Bai Ganio, as much as a desire for a more prosperous life. It also lurks as a longing for a fargone glory, when the Second Bulgarian Kingdom had spanned over the Balkan peninsula. After breaking from the Ottoman rule, Bulgaria felt under-developed, inadequate in the new European context. A sense of inferiority was kindled. Georgi Hadzhyiski9 defines 3 symptoms of this complex:

- 1. A feeling of shame, because every textbook teaches the historical misfortune the nation has endured with many subjugations, slaughter and plunder.

- 2. A feeling of guilt, caused by the occasions when strong leaders were betrayed and the disillusionment that nobody may ever again resemble heroic figures from history books and folk stories.

- 3. Megalomaniac tendencies, aiming to amend those feelings by twisting reality and exaggerating every facet of Bulgarian society, e.g. its uniqueness, strength, intelligence and innate decency and humility.

Megalomania usually uses historical and geographical facts to support its intentions. In 1762, Paisii Hilendarski finished the book История Славянобългaрска (Slavonic-Bulgarian History) where he fitted numerous examples of the great history of the Bulgarian nation. A substantial work which inspired several liberation movements. It becomes problematic, however, when the ‘beating in the chest’ goes out of hand. When Paisii Hilendarski compiled his ‘history’ he picked only the relevant heroic examples of Bulgarian history and left out many not so interesting in order to prove his point. His text is not so much a historical account, as it is a literary masterpiece.10Of course, it did not include any accounts of the Ottoman rule. Three hundred years later this attitude has backfired. And when chalga brought any allusions to the Orient (not Ottoman, but close enough), it hit right in the heart of many. Today, however, with much more refined historical knowledge the Bulgarian nation can build a more grounded approach in order to position itself in the European Union with a solemn acceptance of its disreputable past.

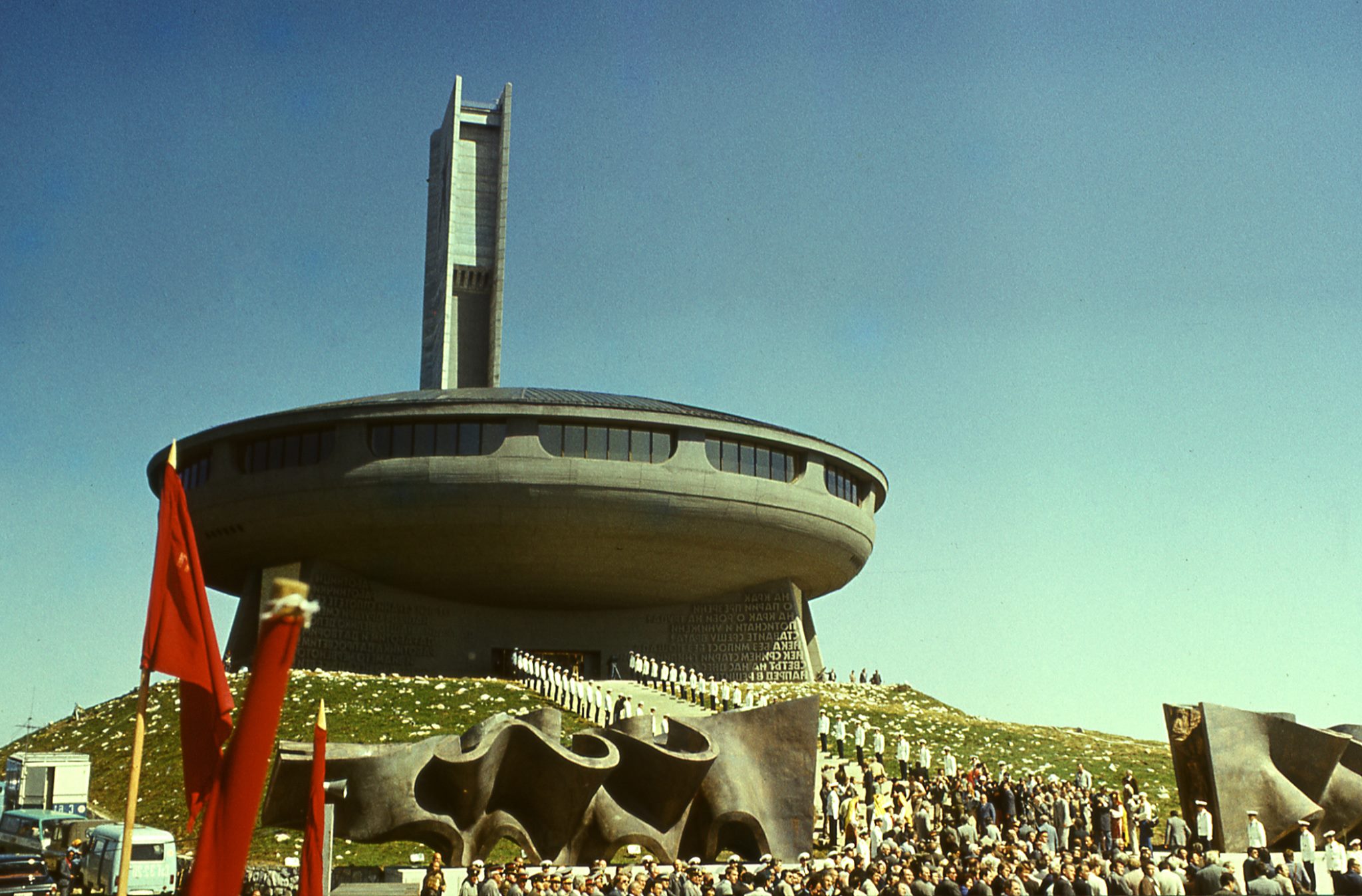

Several hundred years later in 1981, a celebration was held for 1300 years since the founding of the state. I imagine that rudimentary questions of identity arose: What is our ethnos? Where do we come from? What are our traditions? Great monuments11 were built, films were produced and opulent events were organised solely to commemorate the occasion. Furthermore, Socialism brought more than fake confidence in our history, it also introduced socialist values, introduced by the ‘communist morality’.12 These are practically positive and negative character traits that a citizen should consider. Unity, patriotism, honesty, discipline, hard-work are prefered over individualism, hedonism, laziness and disloyalty. Chalga checks all the boxes of traits one would avoid. When democracy came in 1989, Bulgaria started looking away from the East. It was more and more attacked for its lighthearted nature and striking aesthetics and perhaps people had enough of it. It is unclear, but every decade it adapts and people continue to shamelessly and shamefully listen to its pumping rhythm.

The Origins of Chalga

Almost five centuries of Ottoman presence have put a mark on the Balkan cuisine, music, language and morality.13 Nations were forced to adapt to a new unknown culture and religion. Therefore the Balkans share many cultural aspects such as pastries like banitsa (burek) or wedding rituals which involve some kind of ‘abduction’ of the bride. In music, what is mostly present is the oriental melodies and choreography and Romani instruments and rhythms.

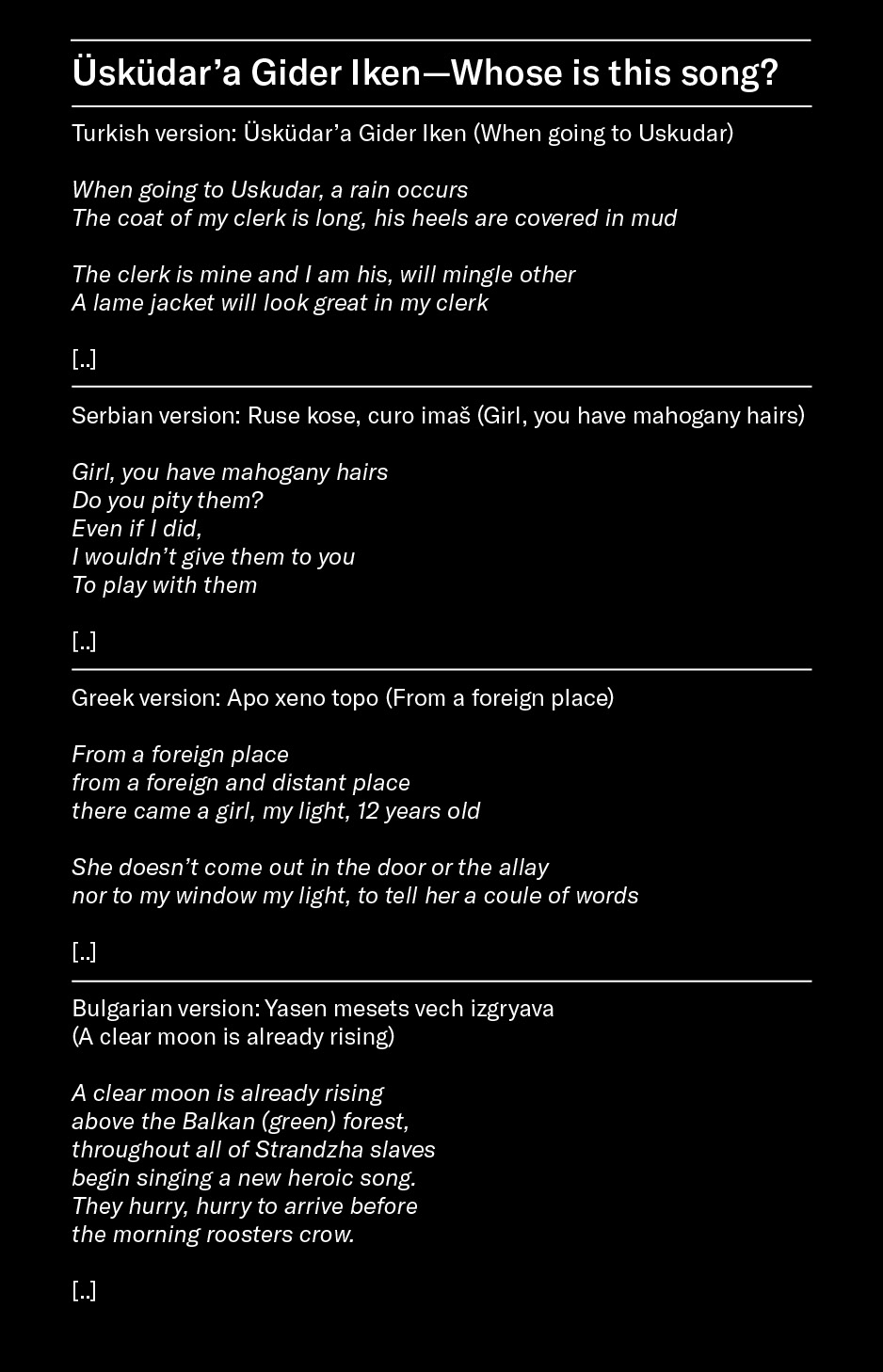

In 1973 the Bulgarian ethnographer Raina Katsarova followed how the song Üsküdara gilder iken (On the way to Üsküdar), originally an Ottoman song, spread through the Balkans.14 Listening to it (Fig.3) one can easily distinguish the oriental flavour, because of the traditional Turkish lute and style of singing. The lyrics tell the story of a woman travelling to Uskudar. On the way there she finds a handkerchief, fills it up with turkish delight and shares it with a clerk in her carriage, who she has been admiring all along.

Some versions15 stayed close to the original such as the Serbian version Ruse kose curo imaš (Red-haired girl) or the Greek one—Apo xeno topo (From a foreign place), where they retell a love story similar to the original. However, the Bulgarian variation Ясен месец веч изгрява (A clear moon is already rising) version is much more militant in its content. This demonstrates (Fig.4) how a song could spread and morph among people who speak different languages but share similar culture.

Furthermore, in Bulgaria the origins of the song and its current meaning clash to create a slight irony. A very patriotic song about protecting the motherland from the Ottoman Turks, currently still the ‘hymn of the Stranzha mountain’,16 that originates in the land of the oppressor. In Adela Peeva’s film Чия е тази песен? (Whose is this song?),17 she asks a group of people if they know the history of the melody in this song. They seem oblivious to its roots and when Peeva reveals ‘They have it in Turkey too!’ a rapid change of mood transforms the confused faces from gleeful to furious. These people have gathered to celebrate an uprising against the Ottoman oppressors and this woman comes to spoil their illusion. One man is so disappointed (Fig.5) by her comment, he tells her that he would ‘stone anybody who claims such a historical connection’.

Peeva ends the film asking herself ‘How could one song incite so much hatred?’ This reaction is not surprising at all. Folk music is taken seriously in Bulgaria, especially when it recorded the struggle of five centuries of Ottoman subjugation. The identity of the ‘Bulgarian free nation’ has been built by juxtaposing the times of suppression with those of freedom. During socialist times, this propaganda against the new Republic of Turkey fostered even a stronger national identity - the identity of ‘pure ethnos’, no Turkish or Roma connections, and ‘pure culture’, no Oriental cultural heritage. Thus it is of no surprise that the socialist regime was censoring the level of ‘chalga’ some wedding orchestras played in the 80s.18

Since many wedding instrumentalists were Roma, they played Roma music, especially a dance called “kyuchek”.19

It was unacceptable to play Romani music at Bulgarian weddings. And to this day Romani people are looked down on when they perform. Or at least until a certain level of sobriety.

In 1989, the Soviet Bloc crumbled and chalga boomed in popularity. Wedding music left the stage to ethno-sound combined with Romani musical elements, oriental eroticism, pure nonchalance of the ‘free spirit’. How could some ‘traditional Bulgarian folk’ music be related to Ottoman or Romani traditions? Nobody cared. No more rules. There were no copyrights, no censorship, people could sing and act however they saw fit.20 Curiously, the music videos did not cross one line. The Ottoman Turkish aesthetic. Arab sheiks (Fig.6) and camels were fine because they were largely oriental, but Ottoman harem and mosques were taking matters too far. Some sort of ‘sanitized images’, too sensitive for Bulgarian audience, which chalga producers replaced with Arabic or Western metaphors.21 In the article, Bulgarian Chalga on Video: Oriental Stereotypes, Mafia Exoticism, and Politics, Vesa Kurkela is examining the place orientalism takes among the audiences of chalga music. He describes the main variations of the videos like this:22

The videos also contain aggressive jokes that display little respect for anyone or anything. The objects of mockery are various—politicians, the state administration, the nouveaux riches, the Bulgarian mafia, policemen, macho culture, the sex business, Arab sheiks, superficial lovers of fashion, Russian folklore troupes, and various Western fashion phenomena. Ironic criticism is often so well hidden that the outsider cannot understand it without the guidance and explanation of local cultural experts. Nothing in chalga is serious and its contents stray very far from Western political correctness.

The post-Socialist period of the 1990s was extremely interesting from social, economical and political perspective. People had just been allowed to express themselves, or rather they were not forbidden to do so it. Years and years of censorship triggered foul language, slutty clothing, large golden crosses prominently hanging on the chest of whoever could afford it. This way people not only did not feel any shame but they were taking pride in showing their vulgarity. A perfect example would be Valdes’s Рибна Фиеста (Fish Fiesta) from 2001. The video (Fig.7) shows a fisherman playing an accordion semi-submerged in a river. From time to time he sways his fishing rod to pull not a fish but the underwear of an attractive woman sunbathing on the shore. If that isn’t enough, he appears to entertain his friends in a tavern having banknotes stuck to his forehead. Apparently, in 2001 the censorship came back because the chorus singing:

- И ловец съм, и рибар съм,

- на закона мамата ибал съм

- (I am a hunter, I am a fisherman)

- (I have fucked the law)

- which turned into the ‘censored’ version:

- И ловец съм, и рибар съм,

- на купона цар и господар съм

- (I am a hunter, I am a fisherman)

- (I am king and master of the party)

Economically, most people struggled to survive and the terrible inflation of 1996 did little good. Dire times call for drastic measures as people tried to exchange Bulgarian levs for American dollars or German marks at all costs. Thus we can presume that people enjoyed listening to music that echoed their absurd lifestyle with a humorous spin. Nelina’s Бял Мерцедес (White Mercedes) shows a reality (Fig.8) where the protagonist is sent to buy dollars. Unfortunately, they do not have any left, but she is being followed by a white Mercedes where a hand from inside offers her dollars. She refuses to ‘exchange love for money’.

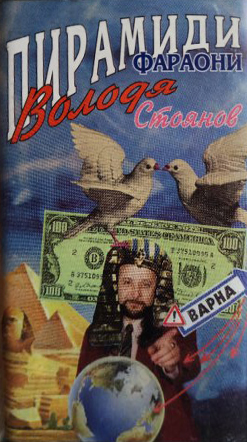

Certain people figured they could exploit the economic turmoil and organised strong men, usually former wrestlers or boxers, to ‘ask company owners to insure their business with them’ or ‘to pay for copyright for the music they play in cafes and restaurants’. Refusal to do so meant that they will lose their business and more. This gave rise to the mutri, or mafia, period from 1994 to 1999. They acquired loads of money using this ‘business model’ until the 2000s when the explicit violence and intimidation waned out. Certain artists were attracted to this and in 1995 Volodya Stoyanov was ‘abducted’ to sing for Vasil Iliev, mafia boss at the time.23 Volodya had reservations at first but got used to performing for him and recorded the album (Fig.9) Пирамиди, Фараони (Pyramids, Pharaohs).

Later in 1996 Rado Shisharkata and Ivan Karachorov–Popa also paid their tribute (Fig.10) by recording an absolute classic track, glorifying the mutri culture, called Тигре, тигре (Tiger, Tiger). They sing to someone (Vasil Iliev presumably) asking him if he has money, beautiful women and expensive Western cars or just old women and rusty Soviet cars. Both of these songs opened the scene for many mutri-songs and chalga became the main choice at most mafia parties.

Chalga was ‘music for the soul’ so politics found no place within it. In Bulgaria ‘politics’ stands for activities associated with the government, not so much for anything ‘concerned with power and status’, e.g. ‘the politics of gender’. However, sometimes people appropriated songs for this purpose. Such is the case with Slavi Trifonov and Ku-Ku Band’s Тайсън Кючек (Tajsyn Kyuchek) which was played (Fig.11) at a protest at the end of 1996 firstly in Lom and later in Plovdiv.24Despite the show Kanaleto, which Slavi and Ku-ku Band were part of, being openly critical the prevailing government of Zhan Videnov, the song is still not explicitly political:

- Седем-осем и ще си паднала

- Седем-осем и ще си легнала

- Седем-осем лягай и брой си сама

- Seven-eight and you will fall

- seven-eight and you will lie down

- seven-eight give up and count yourself

Breaking it down, the anaphora ‘seven-eight’ refers to boxing knock-out, therefore Tajsun is (Mike) Tyson, to imply some threat or taunt. It also refers to kyuchek dance with its asymmetric time signature (7/8), commonly appearing in Balkan music. Although nothing suggest political statements, protesters used it as a count-down for the ‘last hour’ of the government. Slavi Trifonov entered politics more seriously in the last decade. His albums Има такъв народ (There is such a nation) and Песни за българи (Songs for Bulgarians)25 are interpretations of folk songs that were supposed to inspire Bulgarians to reclaim their state. In 2016 Slavi and Ku-Ku Band protested against the state at Orlov Most (major bridge in the centre of Sofia). Although the songs they performed were much more traditional, he is still known as the chalga performer and got a lot of criticism for it. His political motives are dubious, but his chalga influence is not. Some were agitated, some were grateful that a resistance to the state has been formed. Since then Slavi has moved on to create his own TV channel where he is 'free to go his own way’ and share his political views. It is still mainly an entertainment channel, but he is free of official censorship.26 Whether this means there will be more chalga songs that take a political stance is yet to be seen.

The Production Evolution

The songs from the 90s and early 2000s have become true gems within Bulgarian music history. Most people today have good memories from this time. People born in the 50s, 60s, 70s were in their prime age when the genre evolved. It was loud, energetic, rebellious, sexy, melancholic—it connected to all parts of life, good and bad. The children of those people grew up listening to chalga, which in turn brings them good memories.

The music itself was not of the highest quality. The musical instruments were relatively cheap and easy to find but second-rate in quality which meant professionals were not satisfied. Soviet-made instruments were available, but the difference was miniscule. In-demand were East German keyboards and speakers or third- or fourth- hand Fender guitar imported from the West. The sound of those early songs was quite rough, the artist being a singer, musician, songwriter and producer. Nobody was taking it too seriously. Most of the music was light-hearted, exploring the possibilities. By 1992 two companies—Planeta Payner and Ara Music—were founded and have led the industry ever since. They focused on ‘pop-folk’ (the less derogatory term for chalga) and produced music, videos, audio cassettes and superstars. Most of the chalga artists popular in the 90s until today emerged from one of those two companies. In a couple of years everything changed immensely.

Professional songwriters like Nadezhda Zaharieva and Zhivko Kolev27 wrote many Bulgarian Estrada songs in Socialist times and now they were employed again. Songs by Signal, Lili Ivanova and Tangra are known by many Bulgarians. Nowadays they have crafted other absolute hits like Луда по тебе (Crazy about you) and Митничарю (Border guard). Were they happy to do that or not, we don’t know yet… The content of the songs remained lighthearted but technically they were written with a much better flow and rhythm. Perhaps this is one of the reasons these songs are so memorable.

Recording studios and professional sound engineers allowed the artists to acquire top-notch music quality. Producers, stylists, make-up artists were responsible to present the artist in the best way. Rarely a song would be released without an accompanying music video. For the purpose of the promotion or additional profit, chalga videos gained huge success:

At the end of the 1990s the new style became an undisputed success on the Bulgarian popular music scene. The most popular chalga hits sold more than 100,000 copies, whereas domestic rock records could at best reach sales of 10–15,000 copies (Ivo Dochovski and Ventsislav Dimov, Interviews, 1999).28

In the 2000s, the quality continued to grow producing more songs, more videos and more stars. Planeta TV was founded in 2001, followed by Planeta Folk TV in 2007 and got an upgrade to HD in 201029 Early on their artists have joined YouTube and Spotify. Additionally, their Planeta Derby concerts are some of the most visited public venues in the country. In general, Planeta Payner has long overshadowed Ara or any other production house, so much to be called a ‘mastodon’ by the singer Milko Kalayzhiev.

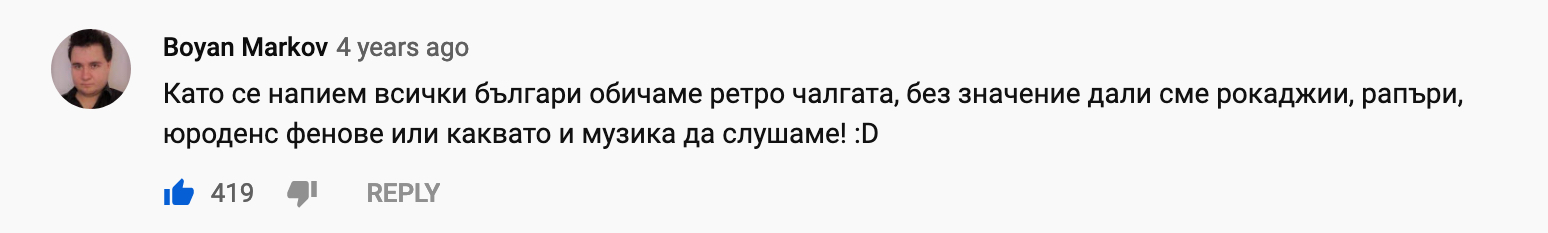

Retrospective collections are compiled since 2004, preserving the ‘top hits of the industry’. Typically these have come to be known as ‘retro chalga’. What defines a song as ‘retro’ is unclear? But it is essential to understand that generally these songs are widely accepted and have acquired a much more nostalgic status. One comment under the video Кожена пола by Dzhesika (Leather Skirt) sums the feeling perfectly:

When we get drunk all Bulgarians love retro chalga, regardless of being metalheads, rappers, Eurodance fans or whatever other music!

There are countless comments like this. And it happens outside of the internet as well. My brother-in-law is a metalhead can start his casual evening with Two minutes to Midnight by Iron Maiden and switch around 2 o’clock in the morning to Седем бели коня (Seven White Horses) by Orkestar Oasis (Fig.13 & 14). When I asked my cousin to talk about chalga she humorously said ‘I don’t listen to the new stuff, only retro chalga’. I wondered what makes the ‘new chalga’ so embarrassing to listen to? When I asked Milko Kalayzhiev, one of the most influential artists in the genre, he revealed how the Estrada performers were deliberately trying to publicly shame chalga. Estrada is a pop genre created during Socialist times as a substitute to Western pop. It projected a vision of love, elegance and chivalry, in accordance to certain Socialist ideals. By contrast chalga radiated eroticism, hedonism and opulence. The bitter truth, according to Milko, however, is that when Estrada fell out of favour, the performers lost their work. It was old, sluggish music that exemplified a long-past age.

For 30 years they have made a couple of new songs. What do you expect from the audience? We produce lots of music. Now we are having a concert with Planeta Payner. Wait and see, it will be sold out.30

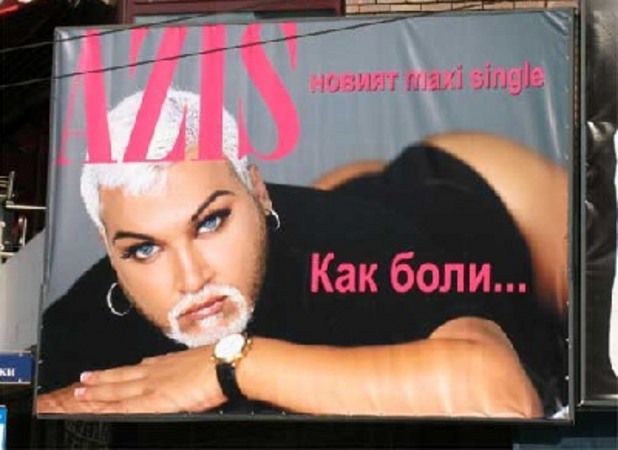

The concert Milko refers to is the annual concert of Planeta Payner where thousands of people show up because it is contemporary, affordable and spectacular. There will be more experienced and newly-emerged performers. For 30 years of history, the genre has changed. Now the songs sound more ‘pop’ (that is Western pop) and include hip-hop and trap elements. However, the occasional clarinet or trumpet solo reminds us it is still Bulgarian music. The artists adapt and their representation goes along. If in 2004 Azis caused a scandal31 with a billboard (Fig.15) that stated ‘Азис Как боли’ (Azis How it hurts) showing his nude ass, now the standards have changed. Some artists go much further with how they present themselves like Suzanita, daughter of the chalga artist Orhan Murad, who also caused a scandal32 because she dressed so ‘indecently’ despite being only 14 (Fig.16). These ‘scandals’ remind us that this is a show-business like any other and attracting attention is just a means to an end.

Nowadays, the general appearance of the chalga artists, after the era of fake boobs and lips, is relatively toned down. Looking at a typical billboard with the faces of the evening’s performers, it does not diverge from Western pop, Estrada or even rock and metal band aesthetics. Many of the chalga artists simply do not need any more scandalous behaviour to be famous due to their reputation or because Planeta Payner uses its massive media network to easily promote them.

Enter the Chalga-verse

In chalga, aesthetics follow content. It is hardly surprising that artists and their videos are opulent, light-hearted and sexual. Looking into overarching themes of wealth and money, enjoyment and peace of mind, love and eroticism and sometimes acute politics, one can start to understand where it all comes from and what chalga represents.

Wealth

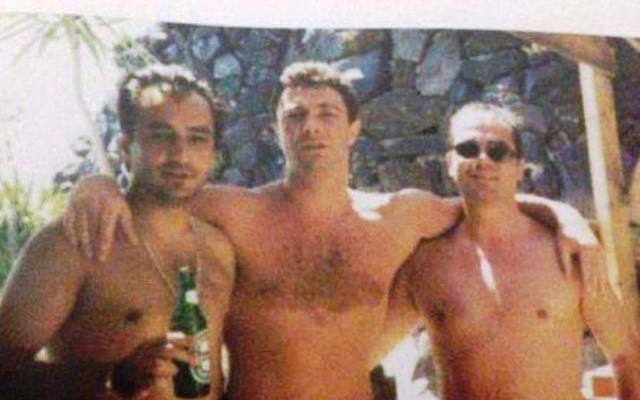

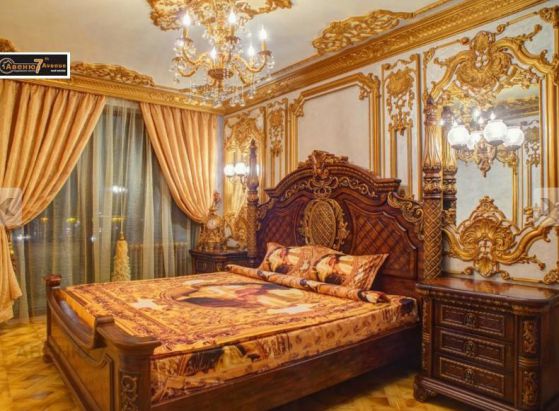

Mafia-baroque or Mutro-baroque33 is a particular aesthetics that the Bulgarian mafia (Fig.17) has acquired in the 90s. Many Bulgarians often considered chalga the music of the new economic elite—the nouveaux riches34 in the 90s and it is not much different nowadays (Fig.18). I have heard people talk about money for as long as I can remember. Bulgarian society is entranced by the idea of being rich, influenced by the rose-tinted vision of the Western life and technically free to achieve anything with no political oppressions.

In Sashka Vaseva’s highly experimental music video Левовете в марки (Levs in Marks) the story revolves around a woman who is looking for a company to have a drink with. She needs to exchange Bulgarian levs for German marks in order to buy alcohol. What a hard task. It just shows how hard it was to do anything in the years of inflation of 1995-1996 with devalued currency. It is even more simple with Kondyo’s Мъни, мъни (Money, money) where the singer sheds light (Fig.19) on the secret of life: money.

That’s what women want, if you have money, everybody loves you, and if you don’t–everybody is gone!

Around this time extremely popular was travelling to Turkey to buy Western goods and smuggle them in Bulgaria in order to make money. If you already had foreign currency and managed to buy cigarettes and jeans from there, you still had to bring it back into the country. In the song Митничарю (Border guard) by Liya we witness all the trouble (Fig.20) she has to go through in order to smuggle her cargo. She is stopped at the border, so the guards can check thoroughly the car. Liya hopes she can easily go through, calls her mother for support and begs the guards. The voice of reason joins her mental process to suggest giving the guards 200 marks. At the end 'they are also people/ they need some for cigarettes and some to build a house'.

Nowadays there are fewer songs specifically about money, but it has stayed a leitmotif nevertheless. In 2013 song За Пари (About money) by Galena no currency is mentioned because it makes no difference. The protagonist is singing about the power and allure of money. She is talking to a beautiful strong man whom she advises that talking ‘about money’ is all he needs. Simply ‘For money, for money, you speak/ this word women love even more than sex’. More subtly, some videos abundantly show wealth to the audience. Prominent in the clothes of the singers and actors, their cars, yachts or planes and the locations the events unravel. A good example is Не Ме Оставяй (Don’t Leave Me) by Fiki and Tsvetelina Yaneva. The video (Fig.21) radiates wealth and money to a microscopic level. We witness a long, pan view of the mansion the video is shot, the elaborate architecture and exotic furniture, all the adorned objects inside ending with a fabulous appearance of the slow-motion gait of Fiki and the flowing silky dress of Tsvetelina.

Enjoyment

To acquire wealth is a goal of many, but sometimes it is more important just to enjoy life. Music on the Balkans has a great tradition of joyful tavern performance at least since the inter-war period,35 where people eat, drink and sing along. Valdes’s Рибна Фиеста (Fish Fiesta) besides being vulgar and provocative, it shows the performer entertaining his guests and friends at a table, where they drink, laugh and enjoy the music. Another classic track is Шопската Салата (The Shopska Salad) by Rado Shisharkata which is simply dedicated to the Shopska Salad, summer salad from tomatoes, cucumbers, spring onion and cheese. It commemorates the little joys in the singer’s life like the salad, the alcohol mastika, blonde girls and his desire to spend all his heaps of money at the seaside, where he can lie on the beach with his loved one under the stars. Additional aspect of this hedonism is excitement which can be more clearly heard in the Нещо Нетипично (Something Untypical) by Ivana. There the singer is done with all the cliches of modern life (Fig.22) and yearns an exciting, wild night out. The very first verse is an imperative ‘Why don’t we get drunk/ let’s break all the foolish cliches/ let’s get wild tonight’. Her appeal for more excitement, an escape from the boring daily life resonates greatly with many people who miss something besides money in their lives.

Eroticism and Love

The most characteristic quality of chalga is its eroticism and love problematics. As we have already established, Romani culture has a tremendous effect on the chalga music and aesthetics. The belly-dance in particular is an erotic element that has transformed and it relies more on the scantily-clad female sex symbols.36 Historically, Bulgaria never had belly-dancing as it was popular in Arabia usually performed by minority groups like the Romani people.37 This eroticism, however, has proven to be a fantastic marketing tool that they have nothing to do with. In the 90s, dancers shook their bodies alongside singers on the stage but with the advance of cable TV this kind of imagery has totally exploded. To a western person, this may seem as too much provocation from a music video full of dancing male and female bodies.

Most music videos in the beginning included lots of Arabic themes where the proverbial belly dancer is capturing our eye. She moves with the rhythm and we gape at her, mentally caressing her flexible body. Appropriating the dance, she has mainly an erotic purpose, usually leading to a very tragic performance. On many occаsions, for example in Milko Kalayzdhiev turbo classic song Къде си, батко? (Where are you, big brother?), the idea for harem, where a man is surrounded (Fig.23) by beautiful playful women, is very prominent. And besides, the themes of the videos, the average look of the female singers is absolutely stunning as they have the most fabulous hairstyles, make-up and body figures. In 1996 Mitko Dimitrov the owner of Payner explained that ‘good look’ is essential for success and if a singer is not so good-looking they use pin-up girls for the cassette covers.38 Nowadays, eroticism holds the same importance, the only difference being more contemporary in fashion.

As most pop songs, however, chalga revolves around love and all its subsidiery themes: heartbreak, infidelity, sex. And this is the big power of chalga: its lyrics. Accused to be ‘laid-back and shallow’ these songs are meant to be summer hits and nothing more. People compare those with folk songs like Земи огин, запали ме (Take this fire, burn me), which are supposedly much more meaningful. A song about a man who cannot live his life anymore chasing his beloved, so she better set him on fire and end his misery. Loads of folk ballads celebrate the love between people. Other comparisons are made with the passionate tracks by Lili Ivanova or Emil Dimitrov, some of the Estrada singers from Socialist times. And even with Stari gradski pesni (Old-city songs) that became popular in the inter-war period.

Despite the difficult times after 1989, chalga also holds a few very intimate songs, which can hardly be accused of profanity. Богиньо моя (My goddess) by Maksim is a deeply sentimental ballad telling the story of someone who sings only about his ‘goddess’ and will do anything to win her heart. Or the female perspective in Погледни ме в очите (Look me in the eyes) by Aneliya where love is portrayed as something ultimate (Fig.24) where no lies, no pain or anger will change it. So overall, it is not so hard to find meaningful songs in a sea of light-hearted and humorous tracks.

Politics

Finally, a side of chalga that is somehow obscured is its political power. In the 90s Valdes and Slavi Trifonov said what they wanted with their music as already mentioned: Рибна фиеста (Fish fiesta) and Тайсън Кючек (Tajsun Kyuchek) respectively. At that time the Bulgarian punk movement also developed strongly, other rock and metal bands stood for their beliefs. In general, the last decade of the 20th century had a lot to unpack.39 With the turn of the century, there were other players in the game. The Hip-Hop collectives like Ъпсурт (Upsurt) and Спенс (Spens) were very political. However, in the 21st century chalga music and producers became more and more intertwined with secular authority. Before every election there are public concerts paid by political parties and as the politicians need to reach the most people, chalga is the logical choice. Of course this does not mean that chalga singers are associated directly with the commissioners' political orientation. Mafia members from the 90s are still in the political circles. And as some chalga singers glorified the mafia then, now they cannot criticise and ridicule the government filled with their old acquaintances.

Visual language as a device for marketing

The aesthetics of chalga videos are anything but boring. Since their genesis they have followed the Western process of production. In the 90s, the typical formula was the MTV video. There were 3 types of clips—documentation of concerts or performances, narrative videos and music-based videos.40 Documentation were and still are very common amongst more traditional folklore videos of the singer, usually accompanied by the orchestra, in a ‘traditional setting’ full of rugs, pottery in a generic 19th century house. Older performances of Tony Dacheva’s Сладка работа (Sweet job) or Kondyo’s Доко Доко (Doko Doko) give perfectly accurate impression (Fig.25 & 26), as well as any video on Planeta Folk TV, Tyankov TV or Rodina TV which position their singers in backyards, taverns and rocks on a river bank.

Narrative videos have linear plots, without much depth, depicting a simple story line based on the lyrics, which the viewer can follow. In the video of Rumyana Ало, такси (‘Allo, taxi) we observe the singer who wants to reach the seaside hitchhiking. She gets into a taxi, Mercedes, almost ends up in an old Trabant, and finally she rides in a Golf. The last one she sings about is a BMW, but we see a Volkswagen. Unfortunately, we’ll never know what happened production-wise there. The narrative simply reflects the lyrics, showing a young woman using her charm to get to the beach. Through the years, the production quality of the clips have drastically improved, but the depth of the story not much. A video (Fig.27) like Нула време (Zero time) by Milko Kalaydzhiev is full of expensive cars and airplanes, shot with high quality cameras and drones but it doesn’t add too much to the song. Milko wants forgiveness from his lover because he made a mistake, she wants to kill him but ultimately they reconcile. The pictures live in their own universe showing the woman getting frustrated with her phone, being with other men or just striding on an abandoned airplane runway with a shotgun on her shoulder.

Sometimes videos break totally free from the lyrics of the singer and build their own world. The aforementioned Левовете в марки (Levs in marks) by Sashka Vaseva is exemplary of absolute visual freedom. Sashka is singing about drinking and money exchange but the video is exploring its own universe. The techno rhythms combined with MIDI violins provide an excellent playground for all kinds of dancing silhouettes, double exposures with fire and erotic close-ups of female and male bodies. Tsvetelina Yaneva’s 2019 song Ангелът (The Angel) is about a love drama that killed the angel in her… However, the clip (Fig.28) is not dramatising this instead it takes a marvellously colourful vaporwave, neo-cyberpunk that is abstract and open to interpretation.

At the end, the visual language of chalga is more than the sum of its parts. In isolation, chalga is pop-music and the tropes it uses can be applied to Western, Latin American or East Asian music. But the mix of new technology, provocative performances, exuberant make-up and jewellery with traditional landscapes and taverns or expensive cars and hotels creates a unique phenomenon.

On Accepting Chalga

The controversial status of chalga provides a multi-angle view by the audience. The artists were showering in fame and acknowledgement, the majority of Bulgarians enjoyed listening to the music. My parents’ generation let their children listen freely to the music and many aspired to become the next superstars.41 Ex-Yugoslavian, Greek and Romanian music was intertwining with chalga and a peculiar Balkan musical exchange formed. The intellectuals were closely following its development and it even intrigued many American and Balkan researchers to deeply analyse the phenomenon. And to this day the discourse around chalga is layered and complicated because it concerns the ‘democratic period’ with all its turbulent political and cultural transitions. What is needed is calm appreciation and criticism of the music.

Other Balkan people seemingly perceive this type of music differently. A Serbian art student from Niš made an iconic representation of Ceca (Fig.29), the Serbian pop queen, to capture the respect people have for her. She transcended being a mere mortal, she became a saint.42 Her wedding in the 90s with the military leader Arkan was an extraordinary event43 (Fig.30) and many of her songs are listened to even today.

That is not to say that all Serbians are proud of turbo-folk and they share it with everybody but there is a discussion around it. In the 90s, some youngsters saw turbo-folk as the music of the peasants.44 People with low culture, simple needs, financially deprived who moved to the city and brought the simplicity with them. The underground scene escaped this reality through hip-hop and techno. Nowadays, what used to be music reflecting the insecurity and injustice of the 90s, have transformed into a scar reminding people what they have heroically endured. Thus the charge of turbo-folk is completely relieved from this pain and people nostalgically celebrate their youth with the most memorable tracks.

In Bulgaria thankfully, younger generations (Mila Robert and Goro) slowly begin to stray away from being ashamed and instead experiment and provoke by positioning it as classical tracks, making cover versions or injecting it in-between techno tracks. The Bulgarian intelligentsia, however, has retreated from the field. They have grown to discuss only very specific areas of society in the Socialist period. There wasn’t much alternative culture at the time anyways. When chalga was developing some of them showed interest and shared their opinions. Academics like Rosmary Statelova45, Kler Levi46, Ventsislav Dimov47 have genuinely been interested in the topic and until this day they produce objective and accurate analyses. Kler Levi talks about the syndrome of the curled eyebrow which is an indicator of the contempt that some academics have against chalga. An article48 of hers was seminal because it shifted the initial problematics of ‘For or against chalga’ to ‘What is chalga and what does it mean for the Bulgarian society?’. In the 2000s with the advance of online blogs and small publications many philosophers, journalist and parvenues have shared their disgust with chalga music and industry without contributing much to the discourse. In recent years there have been many negative news articles analysing chalga and few real in-depth overviews49 I was not surprised when the journalist Martin Karbovsky, who has written about chalga, rejected my request to interview him. Humorously when asked ‘Would you share your reservations for discussing chalga?’ he answered laconically ‘No.’ Overall, chalga is unattractive for academics, at least in Bulgaria. Perhaps there is too much emotions floating around the topic that seemingly they ignore it awaiting its final hour.

Conclusion

But chalga is not dying. It was naturally born from the frustration and celebration of the Balkan person, who desires to belong to a community. Whether this is a community of post-Soviet countries, post-Ottoman states or European nations, Bulgaria wanted to enter a new age. Chalga is not a symptom or a cause for the political, economic or cultural situation. Chalga is a consequence, it is a device to cope with struggle and identity formation. The music was born by centuries of culture-blending and social uproar. The Socialist faux identity of ‘the pure nation’ infected the Bulgarian society with shame for this inclusive history. This remorse always baffled me and I hoped I can partly heal it by delving into the essence of chalga. By defining where chalga comes from, what it reflects and why it is so widely criticised. Hopefully, we can come to terms with our past and understand our present without shame or guilt. Only then we can start changing our society according to our circumstances, abilities and needs.

Afterword

For many years, I didn’t understand chalga or the people who listened to it. But the controversy around it always intrigued me. I understood it is about aesthetics and morals, but did not connect politics or identity with it. The very first time I thought about any connection was when I listened to Valdes’ Рибна фиеста (Fish Fiesta). The moment when he sings about ‘fucking the law’ sparked a link. A link to the stereotypical Bulgarian macho who always knows how to trick the system. And I started listening to more and more songs and to find small bits of information that reflected a piece of history. Sharing this with friends and strangers I was always greeted with the same look— ‘the syndrome of the curled eyebrow’ — because they thought I was joking. Almost always, however, they agreed with me when I gave them a few examples. ‘But today it is only crap...’ they continued when we brought the discussion to current times. I found this so weird: to be so incredibly close-minded and deeply affected by one music genre.

When I started writing, I still got curious looks and a lot of my friends disagreed with me. But most of them were also intrigued to read something on a topic they have always considered unworthy to explore. I did not know why I am writing about it, but during the research what kept me going was the constant paradoxes that emerged. A paradox that people fill the clubs, but the deny listening to it. A paradox that it is something so Bulgarian and yet many are ashamed of it. Recently, the new song of Zarko 52 ле'а разходи (Costs for 52 leva) was released. In essence his song is chalga but paradoxically people do not perceive it as such. They see it as a ridicule of chalga, they look into its meaning, comment on the video (Fig.31) and relate to it.50 But in its purest form chalga is a ridicule of society. So how is chalga not worth discussing, but a joke about it is?

Being a sensitive topic, I wanted to explore many points of view. And I got this wider angle by reading appropriate literature, interviewing many different people and rummaging through social media just so I can understand what comprises this phenomenon. I hope that this research provides a clear understanding of chalga and opens the gateway to new works. Whatever new musical trend comes, it will adapt and continue to entertain people. Discussions, whether chalga is good or not, are useless because it is here and it is not going anywhere.

Immense gratitude to all who helped me writing this thesis: Merel Boers, Füsun Türetken, Dirk Vis, Gancho Kamburov, Tony Chervenkova-Kamburova Stilyana Kamburova-Milcheva, Nadezhda Angelova, Melina Koycheva, Ivana Dimitrova, Iliyan Popov, Alexandra Shopova, Kalina Stefanova, Kylièn Bergh. And all my classmates and friends who had to listen to me going on and on about this music.

Also the intervieews: Gancho Kamburov, Rositsa Yancheva, Nadezhda Angelova, Milko Kalaydzhiev, Gorazd Popov – Goro, Bogomir Doringer

And the support from: Donna Buchanan, whose work opened so much knowledge for me. Jivko Darakchiev, whose film Popfolk (2018) served as a springboard for my work. Mitko Dimchev, who doesn’t know, but his YouTube archive of chalga music videos is an integral part of my work.

Endnotes & Bibliography

- 1. Митко Димитров: Ако на България ще ѝ стане по-добре, готов съм да върна парите (Mitko Dimitrov: If Bulgaria is going to feel better, I will give up the money). www.btvnovinite.bg (Accessed 12 October 2019)

- 2. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 143

- 3. Ibid., 143

- 4. Doringer, Bogomir. 2019. Interview with Bogomir Doringer., min. 6:32

- 5. Levinson, Jerrold. 2015. Shame in General and Shame in Music. In Musical Concerns: Essays in Philosophy of Music. Oxford University Press.

- 6. Чалгизирането на България (The chalgization of Bulgaria). www.dw.com/bg (Accessed 9 December 2019)

- 7. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 148

- 8. Блог на Георги Хаджийски – Българският комплекс за национална малоценност (The Bulgarian inferiority complex). n.d. (Accessed 11 December 2019)

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Дочо Леков – Вечната “История Славянобългарска” (The Eternal “Slavonic-Bulgarian History”). n.d. (Accessed 9 December 2019)

- 11. Проектът “1300 години България” – разточителна грандомания или невиждано културно достижение? (The project “1300 years Bulgaria”). www.bulgarianhistory.org (Accessed 10 October 2019)

- 12. Комунистически Морал (Communist Morality). www.omda.bg

- 13. Buchanan, Donna A. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press, 12.

- 14. Ibid., 3

- 15. Ibid., 3

- 16. Химн На Странджа Планина (Hymn of Strandja Mountain Clear Moon Has Now Come) www.youtube.com (Accessed 6 September 2019)

- 17. Peeva, Adela. Чия е тази песен (Whose is This Song?) www.adelamedia.net (Accessed 6 September 2019)

- 18. Rice, Timothy. 2003. Music in Bulgaria: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Global Music Series. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 77

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Kalaydzhiev, Milko. 2019. Interview with Milko Kalaydzhiev., min. 5:15

- 21. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 163

- 22. Ibid., 143

- 23. Как Мутрите Легализираха Чалгата (How Did the Mutri Legalise Chalga Music). 2009. Мутротека (blog) (Accessed 10 September 2019)

- 24. Трите Забранени Предавания На Слави Трифонов (The Three Censored Shows of Slavi Trifonov). n.d. (Accessed 6 October 2019)

- 25. Има Такъв Народ (There Is Such a Nation). www.slavishow.com (Accessed 10 October 2019)

- 26. 7/8 ТВ: Що за телевизия прави Трифонов? (7/8 TV: What TV channel is making Trifonov?). www.dw.com/bg (Accessed 20 November 2019) 2019.

- 27. Songwriters Nadezhda Zaharieva and Zhivko Kolev

- 28. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 143

- 29. История на Пайнер (History of Payner). www.bg.wikipedia.org (Accessed 6 December 2019)

- 30. Kalaydzhiev, Milko. 2019. Interview with Milko Kalaydzhiev., min. 25:15

- 31. Азис Полемика за Задник (Azis Polemics for an Ass). n.d. (Accessed 12 October 2019)

- 32. Тя е само на 14, дъщеря е на Орхан Мурад и стана сензация (She is only 14, daughter of Orhan Murad and became a sensation). www.dariknews.bg (Accessed 12 October 2019)

- 33. Kamburov, Gancho. 2019. Interview with Gancho Kamburov.,min. 1:05

- 34. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 147

- 35. Buchanan, Donna A. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press, 237

- 36. Silverman, Kerol. 2007. Bulgarian Wedding Music between Folk and Chalga: Politics, Markets and Current Directions. Muzikologija 2007 (January).

- 37. Yamani, Mai, and Andrew Allen. 1996. Feminism and Islam: Legal and Literary Perspectives. NYU Press.

- 38. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 164

- 39. Музиката на 90-те през погледа на едно дете на 90-те (The music in the 90s through the eyes of a 90s child). www.podmosta.bg (Accessed 10 September 2019)

- 40. Kurkela, Vesa. 2007. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Scarecrow Press., 148–151

- 41. Кати - Една Сбъдната Мечта (Документален Филм) (Katy—One Fulfilled Dream (a Documentary Film)). n.d. (Accessed 12 December 2019)

- 42. Dzhurich, Vladislava. n.d. Света ЦЕЦА (Saint CECA) by Vladislava Dzhurich. Icon. (Accessed 20 November 2019)

- 43. Ceca i Arkan - Svadba 19.02.1995. (Ceca and Arkan – Wedding 19.02.1995). n.d. (Accessed 7 December 2019)

- 44. Doringer, Bogomir. 2019. Interview with Bogomir Doringer., min. 32:10

- 45. Стателова, Розмари Константинова. 2003. Седемте гряха на чалгата: Към антропология на етнопопмузиката (The seven sins of chalga) by Rosmary Statelova. Просвета.

- 46. Морална паника по време на преход (Moral panic in the time of transition) by Kler Levi. www.kultura.bg (Accessed 12 December 2019)

- 47. Димов, Венцислав. 2001. Етнопопбумът (The Ethnopop Boom) by Ventsislav Dimov. София: Звездан./Dimov, Vencislav (2001) Etnopopbumăt. Sofija: Zvezdan.

- 48. Морална паника по време на преход (Moral panic in the time of transition) by Kler Levi. www.kultura.bg (Accessed 12 December 2019)

- 49. Dimov, Ventsislav. 2019. За някои медийни метаморфози (как „чалгари“ стават „лидери на граждански каузи“) (About some media metamorphoses (How “chalgari” become ’civil activists’)). Медиалог, no. 5: 8–31.

- 50. “52 ле‘а разходи” - песента на Зарко, осмиваща българската действителност (Costs for 52 leva - the song of Zarko, mocking the Bulgarian reality). www.bgonair. (Accessed 16 December 2019)

Image References

- Fig.1 Map of the Balkan countries www.katehon.com (Accessed 30 September 2019)

- Fig.2 Buzludzha Communist Monument www.buzludzha-monument.com

- Fig.3 Üsküdar'a Gider İken (Kâtibim) www.youtube.com

- Fig.4 Lyrics of the Üsküdara gilder iken (Custom-made image)

- Fig.5 Peeva, Adela. Чия е тази песен (Whose is This Song?). www.adelamedia.net (Accessed 6 September 2019)

- Fig.6 Няма Шега (No Joke) by Kameliya www.youtube.com

- Fig.7 Рибна Фиеста (Fish Fiesta) by Valdes www.youtube.com

- Fig.8 Бял Мерцедес (White Mercedes) by Nelina www.youtube.com

- Fig.9 Volodya Stoyanov’s Пирамиди, Фараони (Pyramids, Pharaohs) www.youtube.com

- Fig.10 Тигре, тигре (Tiger, Tiger) by Popa & Belite Shisharki www.youtube.com

- Fig.11 Тайсън Кючек (Tajsyn Kyuchek) by Slavi Trifonov & Ku-Ku Band www.youtube.com

- Fig.12 YouTube comment under the song Джесика - Кожена Пола (Jesika -Leather Skirt) www.youtube.bg (Accessed 1 September 2019)

- Fig.13 Two Minutes to Midnight by Iron Maiden www.youtube.com

- Fig.14 Седем Бели Коня (Seven White Horses) by Orchestra Kristali www.youtube.com

- Fig.15 Azis’s promotional poster Как боли (How it hurts?) ‘Най-Пошлите Издънки На Чалгата (The Most Indecent Acts of Chalga) www.bgdnes.bg (Accessed 2 September 2019)

- Fig.16 Suzanita’s still from Луцифер и Буда (Lucifer and Buddha) SuzanitaFt. Kaskata - Lucifer &Buddha Lyrics www.youtube.bg (Accessed 2 September 2019)

- Fig.17 Georgi Iliev drinking with friends Георги Илиев лъсна в непоказвана снимка (Georgi Iliev exposed in a never-shown photo) www.kliuki.net (Accessed 16 December 2019)

- Fig.18 A Room in Mutro-baroque style Барокова квартира за 2200 евро в Студентския град www.offnews.bg (Accessed 16 December 2019)

- Fig.19 Мъни, мъни (Money, money) by Kondyo www.youtube.com

- Fig.20 Митничарю (Border guard) by Liya www.youtube.com

- Fig.21 Не Ме Оставяй (Don’t Leave Me) by Fiki and Tsvetelina Yaneva www.youtube.com

- Fig.22 Нещо Нетипично (Something Untypical) by Ivana www.youtube.com

- Fig.23 Къде си, батко? (Where are you, big brother?) by Milko Kalaydzhiev www.youtube.com

- Fig.24 Погледни ме в очите (Look me in the eyes) by Aneliya www.youtube.com

- Fig.25 Сладка работа (Sweet job) by Tony Dacheva & Orchestra Kristal www.youtube.com

- Fig.26 Доко Доко (Doko Doko) by Kondyo www.youtube.com

- Fig.27 Нула време (Zero time) by Milko Kalaydzhiev www.youtube.com

- Fig.28 Ангелът (The Angel) by Tsvetelina Yaneva

- Fig.29 Turbo-folk icon Ceca as an Orthodox Icon by Vladislava Dzhurich Dzhurich, Vladislava. Света ЦЕЦА (Saint CECA) www.ex-yumusic.info (Accessed 20 November 2019)

- Fig.30 Ceca and Arkan’s wedding procession www.youtube.bg

- Fig.31 52 ле'а разходи (Costs for 52 leva) by Zarko www.youtube.bg

Books

- Стателова, Розмари Константинова. Седемте гряха на чалгата: Към антропология на етнопопмузиката (Theseven sins of chalga) by Rosmary Statelova. Просвета, 2003.

- Yamani, Mai, and Andrew Allen. Feminism and Islam: Legal and Literary Perspectives. NYU Press, 1996.

- Levinson, Jerrold. Shame in General and Shame in Music. In Musical Concerns: Essays in Philosophy ofMusic. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Buchanan, Donna A. Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene: Music, Image, and RegionalPolitical Discourse. Scarecrow Press, 2007.

- Димов, Венцислав. Етнопопбумът. (The Ethnopop Boom) София: Звездан. Dimov, Vencislav. Sofia:Zvezdan, 2001.

- Silverman, Kerol. Bulgarian Wedding Music between Folk and Chalg: Politics, Markets and Current Directions. Muzikologija, 2007.

- Rice, Timothy. Music in Bulgaria: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Global Music Series. Oxford,New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Articles

- Митко Димитров: Ако на България ще ѝ стане по-добре, готов съм да върна парите (Mitko Dimitrov: If Bulgaria is going to feel better, I will give up the money).www.btvnovinite.bg (Accessed 12 October 2019)

- Тя е само на 14, дъщеря е на Орхан Мурад и стана сензация (She is only 14, daughter of Orhan Murad and became a sensation). www.dariknews.bg (Accessed 12 October 2019)

- Трите Забранени Предавания На Слави Трифонов (The Three Censored Shows of Slavi Trifonov). n.d. (Accessed 6 October 2019)

- Морална паника по време на преход (Moral panic in the time of transition) by Kler Levi. www.kultura.bg (Accessed 12 December 2019)

- Дочо Леков – Вечната “История Славянобългарска” (The Eternal “Slavonic-Bulgarian History”). n.d. (Accessed 9 December 2019)

- Блог на Георги Хаджийски – Българският комплекс за национална малоценност (The Bulgarian inferiority complex). n.d. (Accessed 11 December 2019)

- Комунистически Морал (Communist Morality). www.omda.bg

- “52 ле‘а разходи” - песента на Зарко, осмиваща българската действителност (Costs for 52 leva - the song of Zarko, mocking the Bulgarian reality). www.bgonair. (Accessed 16 December 2019)

- История на Пайнер (History of Payner). www.bg.wikipedia.org (Accessed 6 December 2019)

- Музиката на 90-те през погледа на едно дете на 90-те (The music in the 90s through the eyes of a 90s child). www.podmosta.bg (Accessed 10 September 2019)

- Как Мутрите Легализираха Чалгата (How Did the Mutri Legalise Chalga Music). 2009. Мутротека (blog) (Accessed 10 September 2019)

- Проектът “1300 години България” – разточителна грандомания или невиждано културно достижение? (The project “1300 years Bulgaria”). www.bulgarianhistory.org (Accessed 10 October 2019)

- Музикалните предпочитания на българите (Musical preferences of Bulgarians). www.rctrend.bg (Accessed 20 November 2019)

- Чалгизирането на България (The chalgization of Bulgaria). www.dw.com/bg (Accessed 9 December 2019)

- 7/8 ТВ: Що за телевизия прави Трифонов? (7/8 ТV: What TV channel is making Trifonov?). www.dw.com/bg (Accessed 20 November 2019)

- Има Такъв Народ (There Is Such a Nation). www.slavishow.com (Accessed 10 October 2019)

- Песни За Българи (Songs for Bulgarians). www.slavishow.com (Accessed 10 October 2019)

- Dimov, Ventsislav. За някои медийни метаморфози (как „чалгари“ стават „лидери на граждански каузи“) (About some media metamorphoses (How “chalgari” become ’civil activists’)). Медиалог, no. 5 (2019): 8–31.

- Животът ни е попфолк (Our life is popfolk). www.capital.bg (Accessed 26 September 2019)

Documentaries

- Кати—Една Сбъдната Мечта (Документален Филм) (Katy—One Fulfilled Dream (A Documentary Film)).www.youtube.bg (Accessed 12 December 2019)

- Ceca i Arkan - Svadba 19.02.1995. (Ceca and Arkan – Wedding 19.02.1995). www.youtube.bg (Accessed 7 December 2019)

- Peeva, Adela. Чия е тази песен (Whose is This Song?). www.adelamedia.net (Accessed 6 September 2019)

Interviews

- Gancho Kamburov, interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, Amsterdam, NL, 25 August 2019.

- Rositsa Yancheva, interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, Amsterdam, NL, 22 August 2019.

- Nadezhda Angelova, interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, The Hague, NL, 20 October 2019.

- Milko Kalaydzhiev, interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, The Hague, NL, 8 October 2019.

- Goro (Gorazd Popov), interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, The Hague, NL, 27 October 2019.

- Bogomir Doringer, interviewed by Nedislav Kamburov, The Hague, NL, 27 November 2019.