Origins

Tim Cook, the current face of Apple stands on the Keynote stage in front of a giant slideshow displaying the design of Apple’s new headquarters.

This particular office is designed to be seamless with nature. It is open, transparent, ‘brings the outside in’ and connects everyone inside to the beautiful Californian landscape. ‘It is additionally powered by a hundred percent renewable energy.’ This receives an enthusiastic round of applause from the audience.

We have entered the realm of glamorous, Instagram worthy workspaces. Über-successful companies have been redesigning their headquarters to reflect current environmentally oriented workplace ideals. Nature in these spaces represents companies’ wealth, concern for their workers and a general environmental woke-ness.

Within the past five years, Apple planted a forest, Amazon grew a jungle, and Google headquarters blossomed into a verdant pasture complete with woodland glades, wildflower meadows and trickling streams—‘a super-charged pastoral dream'.22

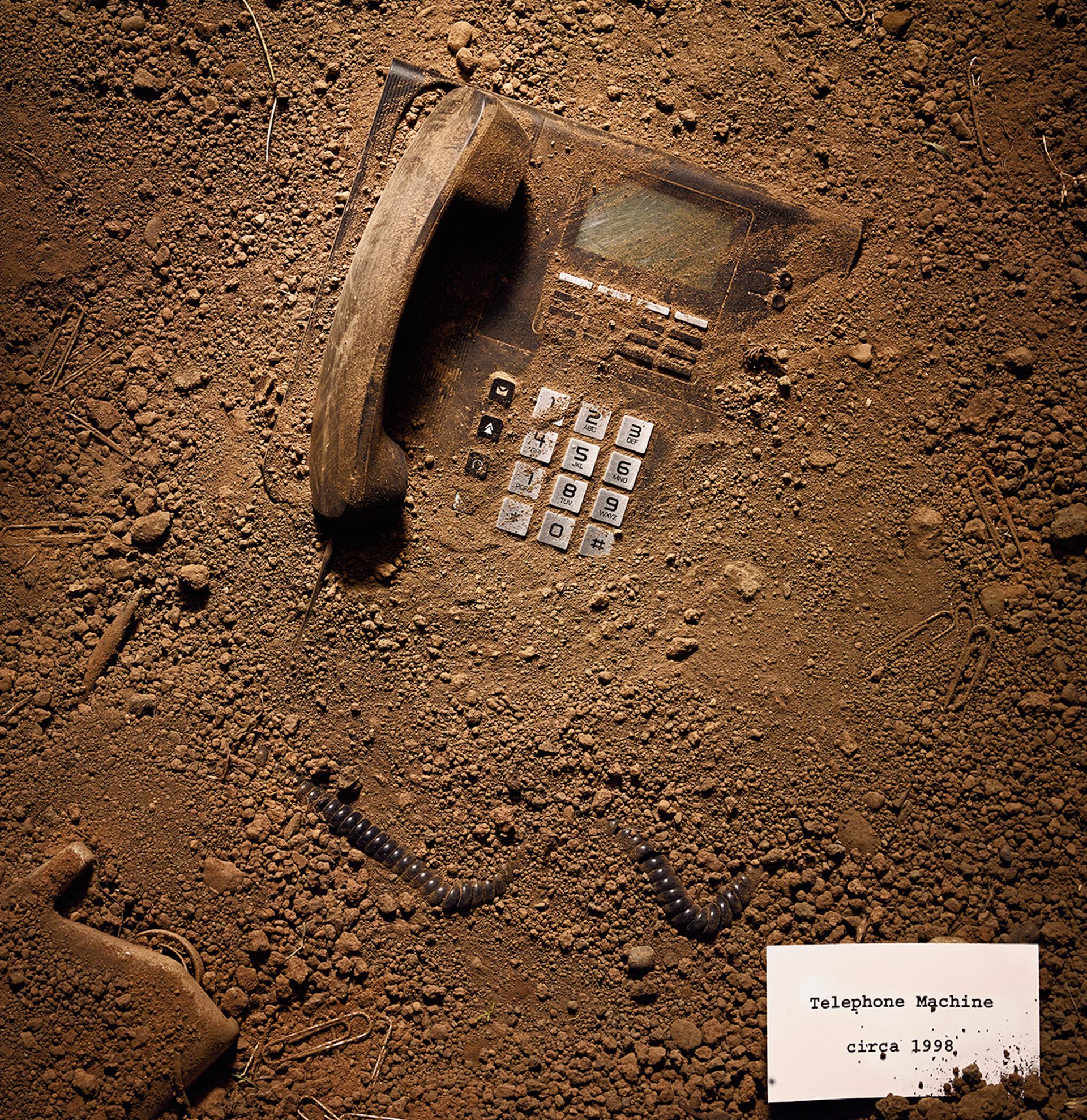

Each of these companies famously began in tiny windowless offices or in their parents’ garages. Who could’ve imagined that the apparent antithesis of nature, the office building, would in turn become a new Eden?

These spaces attempt to physically bridge the severed gap between work and nature. More and more companies are embracing proactive workplace wellbeing programs and promoting it as part of their employment packages in order to attract the best talent. Due to the geographical freedom that recent technology has allowed, there has been a shift towards freelance practices; today, people in the creative industry can technically work anywhere. So the logic in building these over the top, open workplaces is that great staff wants to work in the best possible environment: as a result, workplace wellbeing has shifted towards the top of the agenda. Offices across the globe offer everyday conveniences and staged recreation areas, enticing employees to stay at work well past normal office hours with the presence of gyms and game areas, some even allowing employees to bring pets into the workplace¬—something which for the majority of the workforce remains a quiet pleasure that lingers in the top right corner of a Drop box file.

What makes the glimmering playgrounds of Google offices particularly attractive is that they attempt to dissolve the traditional work/life dyad. As a result of his explorations on this particular duality in the late nineteenth century, Karl Marx hypothesized that the realm of freedom and self-actualization lay beyond the sphere of material production as an external space and time reserved for the restoration of human energy. But today, companies are making a profit by bringing this space into the workplace, now even going so far as to provide the de-stressing nature-fix that people need within the confines of the workplace itself.

Trouble in paradise

We associate these images with the abundance and richness depicted in God’s Garden. The impressively large windows flood these offices with light and fill them with heavenly atmospheres.

The process of reintroducing nature into the urban environment is a good thing—but when we look at it from the intention of increasing productivity, that is where things begin to feel a little sinister.

Seeing photographs of these utopian workplaces and hearing about their well-intentioned practices, it can be hard to imagine the poor working conditions of workers lower down in the company’s chain of production. It can be difficult to even process the contrast between these places. Take for instance the verdant Amazon headquarters jungle in contrast with the exploitative labor conditions of its warehouses; or perhaps the divinely illuminated Apple office compared to its manufacturing plant counterpart, suicide-netting-adorned Foxconn.

FIG. 4: Jan Brueghel the Elder, and Peter Paul Rubens. 1615. The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man. Mauritshuis. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/Explore/the-Collection/Artworks/the-Garden-of-Eden-with-the-Fall-of-Man-253/.

Critique of this divide is not new, it has been represented time and time again in pop culture; those who have more power and more wealth are granted access to more nature in their home and work lives. We think of these mega rich offices as bastions of success; Nathan Bateman’s luxury home/office in Ex Machina, the beautiful office in The Circle—evolved forms of the heavenly garden in Metropolis.

These examples, amongst others, exhibit a certain soullessness and dehumanization that comes along with working in dark, claustrophobic workplaces. The stark contrast between these places perhaps says something broader about how we value workers in the creative, immaterial industry over those engaged in physical or repetitive resource-based labor.

21 CNBC. 2017. “Apple CEO Tim Cook: We’ll Start Moving Into Apple Park Later This Year | CNBC.” YouTube Video. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FhQTsFWG1HU.

22 Wainwright, Oliver. 2015. “Google’s New Headquarters: An Upgradable, Futuristic Greenhouse.” The Guardian. The Guardian. February 27, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/feb/27/googles-new-headquarters-upgradable-futuristic-greenhouse.