This is a Project, Not a Product

Preface

When I first beheld these1 cut-out shapes of various models of contemporary handheld devices, I was overwhelmed by emotion. It came from a feeling of immense comfort, in looking at these familiar shapes. I was left with the urge to investigate the relationship between humans and technology. More specifically, the interaction between humans and technology and how our relationship with information is changing the way cultures think, act, and understand their worlds.

Abstract

This text seeks to investigate the relationship between humans and technology in the process of the becoming of the individual. PART ONE is dedicated to discussing what constitutes and forms the individual, and how technology is integral to that formation. Points of departure are Simondon’s concept of individuation—the individual being a continual process, and Matthew Crawford’s argument on this process being dependent on acquiring skills and gaining competence. Positing that technology is integral to the formation of the individual, it follows that the possibility of that formation is contingent on technical literacy and conceptual literacy. PART TWO gives an analysis of dominant design of technology, and its effects on the individual, culture, and political systems. Making the case that dominant design of technology is applied through a consumer ethic—placing the designer/creator at one end, and the user/consumer at the other—it obstructs rather than foster technical and conceptual literacy. Dominant design of both technical objects and technical systems are clandestinely addictive and manipulative. It can be seen as it manifest in the advent of the smartphone and its apps, social media and its algorithms. From this perspective humans become mere tools of technology, rather than establishing a reciprocal relationship. PART THREE puts forward how to undermine dominant forms of technology. Proposing an educational method, and approaches in art and design, as ways to integrate technology into culture. Wherein, speculative art and design offer a space for reflection; the ethos of hacking and open design—having qualities of share-ability, comprehensibility, alterability—offer various entry points to technological engagement through which theoretical understanding can emerge; and interdisciplinary workshops as spaces where technical and conceptual literacy are fostered.

PART ONE: What Constitutes The Individual

Defining Terms

The use of the term individual in this text is drawn from Simondon’s concept of individuation and Matthew Crawford’s argument on the necessary conditions for the becoming of the individual. There are parallel notions found between Simondon and Crawford in that they both insist that it is types of conflict that are the source for the becoming of the individual. Simondon stresses that the individual is produced, it must coagulate in the course of an ongoing process. Moreover, Simondon’s theory of individuation is not limited to a single human being, rather it describes the dynamic process by which everything arises: technology, living beings, individuals, groups, and ideas. The primary focus however, will be that of an individual’s individuation, and the role of technology in that process.

The Individual is a Process

In "The Genesis of the Individual"2 and "Physico-Biological Genesis of the Individual,"3 Simondon specifies the levels on which individuation occurs. First at the physical level, there is a biological individuation into a living being. The living being then maintains its existence throughout its life in a series of continuing individuations. Prior to individuation, a being has pre-individual potential which is essentially parts that are available for individuation. After the physical individuation, two individuations occur that are in reciprocal relationship to each other: one interior to the individual (called psychic individuation), and the other exterior to the individual (called collective individuation). Once pre-individual components are in a state of individuation, further individuation can happen to any individual, and it can also happen on the level of a group, then called trans-individuation. This applies to a wide range of social formations; as society consists of many individuations composed of more than one person or entity.

The crucial factor here is that individuation is not a result, but an ongoing process whereby the individual is in a perpetual state of becoming. That is, an individual is a process. What then, is the process through which these potentialities come to be actualized? It takes place through a resolution of tensions and incompatibilities, seeking equilibrium pertaining to the system of potentialities. In other words, conflict is a source for the initiation of the process.

A living being faces incompatibility problems with the environment which come in physical form, such as that of hunger, or in the form of negative emotions. These problems compel the individual to action. The tension from these incompatibilities can be resolved interior to the individual (psychic individuation), and others exterior to the individual (collective individuation). The psychic individuation is the formation of the psychology of individuals, and the collective individuation is the formation of how these individual states are linked to the external world. The psychic individuation is itself composed of individuations of perception and emotion. Individuation of emotion involves the self in conflict with self; and perception, the self in conflict with the world. Perception is process where the subject invents a form or model with the goal of resolving a problem of incompatibility between itself and the environment. This process is the idea of personal growth by breaking out of comfort zones. Thus the individual is understood in terms of its relation to the environment from which it requires contact and sustenance.

Individuation of the living being is carried through its successive acts of psychological and social reformation. However, as stated earlier, individuation is not limited to individuals and collectives, it occurs also in technology. The operation of individuation at the level of the technical object4 however, does differ from that of the living being. Individuation of the living being is never perfectly individuated; it is only ever partial and never potentially lacking. The technical object however, draws its individuality (its particularity) from the same operation of individuation that constitutes its initial creation. For example, the digital computer is not any particular computer in time and space. Rather, it is the fact that there is a sequence, a continuity, which extends from the first computers to those which we know and to those still in evolution. The technical being evolves by convergence and by adaption to itself; it is unified from within, according to a principle of internal resonance. This does not mean that there is a linear process that renders the succeeding technical object as merely an improved version of the initial technical object from which it drew on its pre-individual potential.

Say you have two types of computers: A and B. Computer A was created before computer B, and computer B drew from elements of computer A. You have two types of computers, but computer B is not merely an improved version of computer A, as both computers have qualities and functions that each fit better to different operations. Computer A came before and may have a completely different function than computer B, but it may still be better qualified for specific operations. The emphasis is on the continual change or becoming, not its constancy but its continuing ability to grow by altering itself. The possibility of alteration is thus a necessary condition—for the individual, for the collective, and for the technical object.

To return to the individual’s individuation, Crawford insists that for the individual to come into being in the first place, the relationship between the individual and the collective, and the human and non-human, is contingent on the form of communication. Non-human here refers to our environment—the material, the technical, the mediated. Given our current situation of the widespread connected world of computing, and the pervasive presence of technology in an increasingly rich information environment between and amongst humans and technical objects, it follows that technology is integral to the process of becoming.

Technology and The Process of Becoming

When the humanity of another becomes apparent, it is because you have noticed something particular in that person. This particularity cannot be seen without discrimination. As for the person having this particularity, this comes from developing individuality and seeks to be recognized as such. In his book "The World Beyond Your Head", Crawford argues that developing individuality comes from cultivating some particular excellence or skill. In line with Simondon, Crawford contends that this developmental process is contingent on how we encounter other people and how we encounter objects. With reference to Hegel he states, "one knows oneself by one’s deeds, which are inherently social.5 The meaning of an action depends on how others receive them. This implies that individuality too, is something that we achieve only in and through our dealings with others. The question then arises: how can you make yourself intelligible to others through your actions, and receive back a reflected view of yourself? When we act in the world we make a tacit normative claim for ourselves—for the justifiability of the act. The question of justification only arises if you are challenged by another—the person rejects the validity of your claim to be acting with justification. Confrontation leads you to evaluate your actions. This is necessary if you are to own your actions and identify with them as your own.

Humans are embodied beings who use tools and prosthetics in the world. It is a world we act in, not merely observe. Technical activity involves the capacity to perceive and invent new relationships among heterogeneous things, to produce forms. This means that when you acquire new skills, you come to see the world differently, and see possibilities not previously visible to you. Becoming an individual is thus strongly linked to the acquisition of skills and gaining competence, and it is through and with technology that we do so. If we act through and with technology, then it is impending to ask how it shapes our sense of agency. Agency is the question of who or what is acting, and what the intention behind the action. If we do not know who or what is acting, then how can we hold the action up for contestation? When acting with and through technology, how can we have control of the action, or in other words, how can we know that the intent is congruent with the function. If individual agency is contingent on a reciprocal and collaborative relation between humans and technology, then it follows that the possibility of this relation relies on technical and conceptual literacy. Meaning, there is need for a social pedagogy of technics aimed at the integration of technology into culture.6

PART TWO: Dominant Design of Technology

Sleek Surface, Rounded Corners

Dominant design of technology however, seem to engender an epidemical obscurantism. It can be seen in the general societal rejection of technical understanding as it manifests in the advent of sleek and shiny black box7 devices, platforms, and services, from the smartphone to self-driven vehicles. Our interactions with these devices form experiences that are highly mediated (both in encountering objects and encountering other people). In turn, individual agency, the experience of seeing direct effect of your actions in the world and knowing that these actions are genuinely your own, and acquiring skills and gaining competence, may become not only elusive but illusory.

Habit-forming Technology

There are designs which foster a reciprocal relation between humans and technology, and there are designs which obstruct it. Before elaborating on the former, the following will first give an analysis of the latter and its socio-cultural and political implications.

Consider the design of the smartphone, and the products and services it contains. Products and services come in the form of software applications—apps. You interact with the device and its apps through predefined motions on its sleek surface, known as touchscreen gestures. These gestures are performed with ease and the apps are most often simple and easy on the mind to use. Why are they designed this way, and what kind of relationship does it form between the individual and the collective, and the human and non-human? The most common uses of the smartphone are making calls, taking pictures, instant messaging, social media, watching videos, and gaming. There are numerous apps for each of these categories. What is the intention that guides the design and dissemination of the smartphone and the major social media platforms—YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Pinterest? These products and services rely on advertising revenue—the more frequently we use them, the more money they make. It follows that the aim of their design is to harvest attention. They do this by manufacturing habits, and there is a formula for how to do that.

Nir Eyal, a business entrepreneur, has laid out a business model for how to build habit-forming technology. He calls it The Hook Model: a four-step process companies use to form habits. The four steps are: trigger, action, reward, and investment, which are based on the psychology of human behavior.8

First step: Trigger

An external trigger is something that prompts a user to action. This sensory stimulus is delivered through any number of things in our environment. Digital examples are the play button, e-mail icon, an app icon, or the log in and sign up buttons. Then, internal triggers are built, which involves making mental or emotional associations with the product. So for instance, feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness, will prompt an action to remedy the negative sensation. A habit-forming technology seeks to solve the users’ negative sensation by creating an association so that the user identifies the technology as the source of relief. For Instagram for example, the app icon and the push notifications serve as external triggers to get users to return to the product. The fear of losing a moment instigates stress, and this negative emotion is the internal trigger that brings users back to the app. A trigger is followed by the action: the behavior done in anticipation for the reward.

Second step: Action

Based on research and studies by psychologist B.J. Fogg, Eyal explains that the less effort it takes both physically and mentally to perform an action, the more likely humans are to perform it. Herein lies the reasons behind the ease of the tap gesture and the simplicity of social media homepages where you are prompted to register or login. Other actions are scrolling for rewards in ones media feed at an ungodly hour, and frequently pressing the home button to check for social connection. After the action, the reward follows.

Third step: Reward

In an experiment conducted in the 1950s by psychologist B.F. Skinner, it was revealed that humans seek rewards in three forms: (1) social rewards (we seek to feel accepted, attractive, important and included), (2) rewards of resources and information, and (3) intrinsic rewards of mastery, competence and completion. Media feeds for instance, are algorithmically designed to take advantage of rewards associated with the pursuit of resources and information. The stream of limitless information is filled with both dull and interesting content. So when you log in to a platform, one of ten items may be interesting, or one of a hundred, and this is the reward. To gain more rewards all you have to do is keep scrolling. Checking your notifications and feeling the need to click on each of them, is an example of how the search for mastery and completion moves users to habitual and often mindless actions. The number of unmarked notifications represents a goal to be completed.

Fourth step: Investment

In the 1990s, Fogg conducted an experiment9 showing that reciprocation is not just a characteristic expressed between people, but also a trait observed in how humans interact with machines. We invest in technical objects’s products and services for the same reasons we put effort into our relationships. In congruence, the last step of the Hook Model is investment. Investment enables the accrual of stored value in the form of content, data, followers, reputation, or skill. The more users invest time and effort into a product or service, the more they value it. Storing value in the form of content for instance, would be the followers, playlists, likes, and comments. In aggregate, it becomes more valuable over time and thus the service and product tied to it becomes more difficult to leave as the personal investment grows. Another form of investment is skill. Investing time and effort into learning to use a product is a form of investment and stored value.

Designed to Foster Distraction and Disengagement

The major social media platforms are exemplary of designs based on The Hook Model. Pinterest in particular is an encompassing example of this. The internal trigger for users on Pinterest is often boredom. Once you have registered the only action required is to scroll, and in return you are provided with rewards. It displays rewards surrounding the hunt for objects of desire—images. The rewards of the tribe come from the variability of posting images as a communication medium. And users invest in the site every time they pin, re-pin, like, or comment on an image. Through the notifications of when someone else contributes to the thread, the user is triggered to visit the site again. It becomes a constant loop.

Psychological irritation is something that compels us to action. It is, as shown, part of our brains operating system. What are the consequences of relieving these negative sensations through the aforementioned technologies? If we seek skill and competence and pursue this through and with technologies that are designed to relive us of these negative sensations by mindless and effortless activity, what are the skills and competences acquired? Is the act of caressing your touchscreen a valuable skill? The contents of your feed—the two-second visual puns, click-bait headliners—is it valuable information? And have these habits replaced our time spent on concentrating on more difficult and demanding tasks10 required for personal and professional development, that is, education?

We endlessly hear about how fragmented our mental lives have become—diminished attention spans and a widespread sense of distraction. This is often related to some new study11 reporting how our brains are being rewired by our habits of information gazing and electronic stimulation. The attractions of our attentional environment that we willingly invite into our lives (our feeds) and the unwanted intrusions (advertising) are both troubling in form. If this is the dominating form of stimuli, it leaves little time for higher order thinking involved in education. Education form individuals, and requires powers of concentration and a focus on cognitively demanding tasks that are not immediately gratifying. This is a threat if our mental capacities are exhausted by distraction. In our frenetic technology age, our distractibility seems to indicate that we are incapable of taking a position on the question of what is worth paying attention to—that is, what to value. What is at stake of human flourishing if our need to acquire skill and competence is psychologically satisfied by means of manipulation? This tendency is one of disconnection, and stems from a peculiar consumer ethic. Disconnection—tapping or swiping to make something happen—facilitates an experience of one’s own will as something unconditioned by all those contingencies that intervene between an intention and its realization. How then, with our fragmented mental lives, are we to maintain a self that is able to act according to settled purposes and ongoing projects, rather than distractingly float about? This question is meant both on the level of the individual and on the level of the collective. What are our common aims, how do we discuss going about achieving our aims, and what are the results of going about it? These questions are especially important considering our engagement with these technologies, being a form of addiction, are replacing activities that contribute to personal, professional, spiritual, emotional or social development.

It seems the designers behind our sleek screens and its deliciously rounded corners are intent on keeping people in the category of consumers. They are designed to foster distraction and disengagement. Much like the factory worker, we become tools of technology.12 Not only are we severed from embodied agency, we are severed from political agency. Can the tap gesture on a sleek screen be a kind of agency? Or is this gesture, so entirely emblematic of contemporary life, just an empty notion of human agency? Has choosing from a menu of options replaced doing for the finger-tapping smartphone gazer?

Social Media, Addiction and Manipulation

Interface Feature: The News Feed

The Hook Model explains how tech companies have achieved massive-scale addiction to smartphones and its applications. But its not only our habits that are manufactured, it is our thoughts and beliefs. That is where manipulation comes in.

An interface feature which does exactly that, is the News Feed. The stated intention of the News Feed is to solve our fragmented mental lives, our distractibility. It is a design-solution to the problem of our inability to handle the overwhelming vast amount of information. As Mark Zuckerberg boasted back in 2013, the News Feed turned Facebook into a “personalized newspaper”.13

In his book, "World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech",14 Franklin Foer explains the mechanisms of the Newsfeed. It gives users a non-chronological index of their friends posts, articles, comments, photos, and likes. Based on the user’s behavioral-data Facebook’s algorithm chooses what should end up in the user’s News Feed. The algorithm chooses a batch of choice items from all the possible posts, and decides what the user should read first. When the slightest of changes are made to the code, Facebook changes what its users see and read. Foer proceeds:

It can make our friends’ photos more or less ubiquitous; it can punish posts filled with self-congratulatory musings and banish what it deems to be hoaxes; it can promote video rather than text; it can favor articles from the likes of the New York Times or BuzzFeed, if it so desires. Or if we want to be melodramatic about it, we could say Facebook is constantly tinkering with how its users view the world—always tinkering with the quality of news and opinion that it allows to be viewed. Basically, adjusting the quality of political and cultural discourse in order to keep the attention of users for as long as possible.15

Not only are many users completely unaware of the existence of Facebooks algorithm, but when the company concedes its existence to reporters, it manages to further mystify the algorithm in impenetrable descriptions.16 This is not particular to how Facebook’s News Feed operates, it extends to all major social media platform feeds. What seems to be similar in all cases is that the computer scientists behind the lines of code, do not entirely understand the technology they have built, that is, why the algorithms are producing the behavior observed.

Where Facebook probably never intended for something like the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, and Google and Youtube never intended for cultural output to tend towards negative distortions of the world, it shows the incomprehensibility of the technologies that we (computer scientists) have built.17 Before getting into the details of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, and Google and Youtube’s influence on cultural output, let’s take a look the contingencies of their algorithmic practices and processes of datafication.18

Building a Personality Profile Based on Digital Traces

Tech companies do the addicting, and its paying customer, the advertisers, do the manipulation.19

Again, for tech companies, the more time we spend using their products and services, the more money they make, that is their incentive to do the addicting. The advertisers interest is in using social media as a marketing tool to target groups of people for their ads—not only to decide who to send the ads to, but when to send them and how the ads should look like in order to enhance persuasion. In order to take advantage of all the marketing tools available through Facebook’s platform, user data needs to be collected, re-packaged, and sold, which is how our social and cultural data currently functions within the data brokerage ecosystem20 of marketing and advertising.

The way it works is well illustrated by the project Data Selfie21, created and developed by Hang Do Thi Duc. Data Selfie is a browser extension that tracks your behavior while you are logged into Facebook. It tracks what you look at, how long you look at something, what you "like", what you click on, and whatever you type, whether you post/send it or not. It then shows you your own data traces and reveal what machine learning algorithms could predict about your personality based on that data.

Your personality profile is based on what is called the OCEAN model within the field of psychology. Each letter in the OCEAN model represents technical terms for a personality trait: Openness is a trait that shows how open a person is to new experiences, whether one prefers novelty over convention; Conscientiousness is the extent to which a person prefers organized or a flexible approach to life, and is concerned with the way one controls, regulates impulses; Extroversion is the extent to which a person enjoys company and seeks excitement and stimulation; Agreeableness reflects individual differences in cooperation and sociability, referring to how a person expresses their opinions and manages their relationships; and the trait Neuroticism refers to the dose of negative emotions one has, and concerns the way a person copes and responds to it.

People who land low in the trait Openness will tend to be more conservative and traditional, and people who land high on this trait tend to be liberal and artistic. People who land low on the trait Conscientiousness will tend to be impulsive and spontaneous, and people landing high tend to be organized and hard working. People landing low on the trait Extraversion will tend to be more contemplative, and people landing high will tend to be more engaged in the external world. People landing low on the trait Agreeableness tend to be competitive and assertive, and people landing high tend to be more trusting and keen to team work. Landing low on the trait Neuroticism, are people who are more relaxed and laid back, while the opposite is true for those landing high on this trait, and are therefore more prone to stress and anxiety. Moreover, it has been shown that these personality traits can determine whether you will lean more left or right politically.22

With this sort of information on many users you can decide on what sort information to present them with and how you want that information to effect them.23 Perhaps a certain kind of message might appeal more to extroverts, or narcissists, or agreeable people. In this way you can start to influence their moods, their thoughts and their behavior.

Conducting Experiments on Facebook Users

Facebook has their own research department, entirely dedicated to using psychology to change what people are thinking and their behavior. They do this by conducting experiments on users. Together with academics from Cornell and the University of California, Facebook sought to discover whether “emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness.”24 To conduct this experiment, one group of users saw primarily positive content in their News Feed, and the other group saw primarily negative content. Each group wrote posts that echoed the mood of the posts they saw in their News Feed. The study concluded: "Emotions expressed by friends, via online social networks, influence our own moods, constituting, to our knowledge, the first experimental evidence for massive-scale emotional contagion via social networks."25

In another such experiment,26 showing the emotional and psychological power of Facebook, was in 2010 when they managed to increase voter turnout by compelling virtuous behavior. Through the many Facebook experiments, the company has acquired a deeper understanding of its users than they possess of themselves. For Facebook the aim is to be able to give people the things that they want and things that they do not even know they want. The problem is that the algorithms are not prioritizing truthfulness or accuracy, sorting out misinformation, authoritative reporting or conspiratorial opinion, but rather prioritize user engagement. Because that is how the algorithms operate.

This is not particular to Facebook’s algorithms. All the data that Google can get on you—from e-mails, watched videos, likes, comments—is read by algorithms and compares you with other people who share similar traits, and then Youtube suggests a video to you that is designed to, on the one hand, maximize your engagement, and then shows you an ad that has shown to be effective on the people whom you share those traits with.

Algorithmic Practices, Negative Emotions, and the Spread of Misinformation

In traditional behavioral studies (like those developed by B.F. Skinner, the Skinner Box), an animal or a human would be given a treat (reward) or something like an electrical shock (punishment), and you would go between positive and negative feedback. When the behaviorist researcher would try to determine whether positivity or negativity is more powerful, they were found to be roughly equally important. As computer scientist Jaron Lanier explained in an interview27, "the difference with social media, is that the algorithms that are surveilling you, are looking for the quick responses. And the negative response, like being startled or irritated, tend to rise faster than the positive responses like building trust." Lanier continues, "unlike a trusted news source, which has a longer time span by which you measure success, and thus have to gain viewership by a process of days, weeks, years, and build a sense of rapport with the viewerships, an algorithm just looks at instant responses, trying to get you to engage as long as possible. And this type of immediate engagement is most often gained by negative responses. This means for the algorithms there is more engagement possible in promoting ISIS than there is in promoting the Arab Spring", which in turn means we do not get a balanced view on what is going on in the world. And so for some percentage of people, it will have the effect of making them needier when they are making a purchase, more agitated around election time, and so forth.

With personality profiles based on online behavior, micro-targeted advertising, and negative emotions being more effective, there are dire effects on individuals, and on the larger scale, it has influenced our cultural outputs and political systems, and even our perceptions of these systems and how they work.

Effects on the Individual

Articles on the effects of social media usage on the individual, citing some neurological or psychological study, often iterate the correlation between the decline in mental health and the rise of social media use.28

In a study29 published in the US National Institute of Health, and written about in Harvard Business Review,30 researchers sought to investigate the relationship between social media use and well-being. Their measures of well-being included "life satisfaction, self-reported mental health, self-reported physical health, and body-mass index (BMI)", and their measures of Facebook use included "liking others’ posts, creating one’s own posts, and clicking on links." The results showed that the "measures of Facebook use in one year accurately predicted a decrease in mental health in a later year." Specifically, liking others’ content and clicking links could predict a significant and subsequent "reduction in self-reported physical health, mental health, and life satisfaction."

Humans have a psychological tendency to compare ourselves to others to make judgments about ourselves. We make "upward social comparisons, in which we compare ourselves to people we consider better off than we are, and downward social comparisons, in which we compare ourselves to those who appear worse off." Self-comparison on social media leads to making conscious decisions about what we will post and share in order to achieve certain social goals. This is what is known as selective self-presentation, where the goal is to make ourselves look as attractive, popular, successful, enviable as possible.31 Earlier studies reported similar effects, as stated in an article published in Psychology Today,32 (1) "the more time users spend on Facebook each week, the more likely they are to think that others were happier and having better lives than they themselves"; (2) looking at social networking profiles led to a more negative self-body image; (3) "men who viewed profiles of successful men were less satisfied with their current career status than men who viewed profiles of less successful men." It should also be noted that personality traits (based on the OCEAN model) can play a large role in ones susceptibility to the negative impacts of the quantity of social media use. People high on the trait Neuroticism for instance, are at a higher mental health risk on social media: "People who worry excessively, feel chronically insecure, and are generally anxious, do experience a heightened chance of showing depressive symptoms. As this was a one-time only study, the authors rightly noted that it’s possible that the highly neurotic who are already high in depression, become the Facebook-obsessed."33 Another example showing the decline in mental health is the correlation between the rise of teen suicide and the rise of use of social media, as shown in the recent study published by Clinical Psychological Science,34 and an earlier study by US National Institute of Health.35

What is consistent throughout the studies is that the exposure to the carefully curated images from others' lives leads to negative self-comparison, and the quantity of social media interaction may detract from more meaningful real-life experiences. If the research is any indication, essentially our emotional conditions and moods are being manipulated, and our habits around social media usage, being a form of addiction, has indeed replaced our time spent on concentrating on more difficult and demanding tasks36 required for personal development.

Effects on Cultural Output

Algorithms are becoming increasingly adept at creating content, be it news articles, poetry, visual art. Text-based content is already a common place task for computers, as seen with smartphones operating systems’ ability to predict word sequences. But with visual mediums,37 not only does a computer need to predict a logical thought, it also needs to visualize that thought in a coherent manner. This is a challenge, and with the combination of digital systems and capitalist incentives, it has had disastrous consequence on our cultural output.

In an article,38, artist James Bridle documented the way YouTube’s algorithmic curation drives enormous amounts of viewers to content made purely to satisfy those algorithms. The series of videos in question are being watched by very young children, and consist of an uncanny mixture of nursery rhymes, non-sensical storylines in which low-quality 3D models of cartoon characters meet gory violent ends. The production process of these videos and the intention behind them is not clear, but are seemingly computer generated with seemingly algorithm-chosen titles.39

What seems to be happening is that parents leave their child to watch a cartoon on YouTube, perhaps from a verified channel, and from there, as the "related videos" playlist autoplays, children end up watching abusive violent content. Regarding trusted sources, when an established creator or a brand, business, or organization has an official channel, Youtube grants the channel a verification badge. In this way the content on the channel is supposed to be deemed to come from a trusted source. As Bridle points out however:

One of the traditional roles of branded content is that it is a trusted source. Whether it’s Peppa Pig on children’s TV or a Disney movie, whatever one’s feelings about the industrial model of entertainment production, they are carefully produced and monitored so that kids are essentially safe watching them, and can be trusted as such. This no longer applies when brand and content are disassociated by the platform, and so known and trusted content provides a seamless gateway to unverified and potentially harmful content."

But the traumatizing nature of these YouTube videos are essentially beside the point.

To expose children to this content is abuse. We’re not talking about the debatable but undoubtedly real effects of film or videogame violence on teenagers, or the effects of pornography or extreme images on young minds. Those are important debates, but they’re not what is being discussed here. What we’re talking about is very young children, effectively from birth, being deliberately targeted with content which will traumatise and disturb them, via networks which are extremely vulnerable to exactly this form of abuse. It’s not about trolls, but about a kind of violence inherent in the combination of digital systems and capitalist incentives.

The architecture YouTube and Google have built to extract the maximum revenue from online video is being hacked by persons, whether deliberate or not, abusing children at a massive scale. We have built technological systems that have engendered the situation where human oversight is impossible. This expands to not only child abuse, but also the emergence of “white nationalism, violent religious ideologies, fake news, climate denialism, 9/11 conspiracies”.

Cultural content is being created and operate in an architecture where metrics work towards maximum engagement. The highest prize for maximum engagement are negative emotions. With negative emotions being more effective, negative distortions of the world are presented to you. How could meaningful interactions, empathy and respect for difference, thrive in such an environment? Meaningful interactions—the time we spend, and what we give our attention to—are a matter of values. Software-based social spaces like YouTube has no incentive to support those acts and ways of relating.

Effects on Political Systems

A prime example of how algorithms are influencing our public discourse and political systems, is the case of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal. What it emphasizes is that if our emotional states and thought patterns can be influenced through Facebook in the interest of its paying customers, the advertisers, then it is not unthinkable that this method can be used for political aims, such as getting users to vote for a particular party.

Cambridge Analytica: A Case Study

Cambridge Analytica is a global team of data scientists, PhD researchers, psychologists, and digital marketing experts. With the power of big data they conduct targeted advertising. Big data40 is the combination of everything we do, both online and offline, which leaves what are called digital traces. Digital traces41 are stored from things like clicks on links, the online movements and purchases we make with our credit cards, the games we play, the communication we engage in, every search we type into Google, everywhere we go with our smartphones, every “like" or share on our social media accounts, and so forth. This data can be bought by firms such as Cambridge Analytica from a range of different sources: registration at educational institutions, land registries, automotive data, consumer data, voter-registration data, club memberships, cellular plan, magazine subscriptions, religious affiliation.42 Such information is sold by what are called data brokers.43 Cambridge Analytica aggregates this data with online behavioral data such as Facebook “likes” and creates psychological personality profiles based on the OCEAN model mentioned previously. Combining predictive data analytics, behavioral sciences, and innovative advertising technology, they can define "who should be targeted, how the messages should be constructed, and make sure the right message gets to the right person."44 The messages are delivered on multiple platforms across TV, laptop, desktop, mobile, and other connected devices "to reach the targeted audiences wherever they are."45

The Republican Campaign’s Interest in Cambridge Analytica

The reason Trump’s campaign was interested in using Cambridge Analytica, was their promise to be able to build psychological profiles of vast numbers of people by using Facebook data. Those profiles, in turn, could be useful to tune the political messages that Cambridge Analytica sent to potential voters. How they were able to build psychological profiles based on Facebook data, actually begins in 2008 when researchers at Cambridge University launched a small Facebook app called MyPersonality.46 The aim was to encourage users to answer questions on an online quiz to learn about themselves. It included a handful of psychological questions from the OCEAN model questionnaire. Based on the evaluation, users received a personality profile stating where they land on a scale on each of the personality traits. Then the researchers compared the results with all sorts of other online data from the subjects:47 what they “liked”, commented, shared or posted on Facebook, or other basic user information like gender, age, relationship status, place of residence, and so on. This enabled the researchers to make correlations. Each piece of such information is too weak to produce a reliable prediction, but with thousands of individual datapoints combined, the resulting predictions were incredibly accurate. This accuracy was shown by how well the model could predict the user’s answers. By 2012, the researchers published a paper48 proving that easily accessible digital records of behavior–Facebook "likes"—could be used to automatically and accurately predict a range of highly sensitive personal attributes, including: sexual orientation, ethnicity, religious and political views, personality traits, intelligence, use of addictive substances, parental separation, age, and gender. With more than 300 “likes” of a given user, it was possible to surpass what that person thought they knew about themselves. But it was not only “likes” that revealed ones personality traits. The researchers could ascribe the traits of the OCEAN model based on how many profile pictures a user had on Facebook, or on how many friends, which is a good indicator of the trait Extraversion.49 Even when a user is offline the motion sensor on smartphones reveal how quickly one moves and how far one travels, which correlates with emotional instability. In conclusion, the smartphone is a vast psychological questionnaire that users are constantly filling out, both consciously and unconsciously.

Cambridge Analytica coopted these findings with the aim to use the data that they had gathered to micro target American voters by personality type. That same year, Alexander Kogan, a Cambridge University researcher, provided the firm with apps on Facebook that gave special permissions to harvest data not just from the user of the app, but also access their entire friend network and harvest each of their data as well.50 These apps, much like MyPersonality, came about in the early years when Facebook had quite lax data policies. They included FarmVille and quizzes like Which City Should I Live In, What Animal Am I, etc. In a technical sense, Facebook facilitated Cambridge Analytica by having such apps with special permissions. The permissions include the following categories of authorization requests:

(1) access basic information (2) send user e-mails (3) post on user wall, (4) access user data any time, (5) manage user pages, (6) access photos and videos, (7) access friends’ information, (8) access posts in user news feed, (9) online presence, (10) access user family and relationship, (11) access facebook chat, (12) send user SMS messages.51

Based on the data extracted from the user’s basic information, one could build a decent picture of that person’s social world, including a substantial amount of information about their friends. According to a Cambridge Analytica data scientist, in the span of 2-3 months they had collected 60 million profiles of US citizens.52 The Facebook data they collected then became the basis for the algorithms written to target US citizens. They knew what kind of messaging users would be susceptible to, including the topic, content, framing and tone of the message. They would also know when and where the user would be consuming this message. Their team would then create a pathway for the user to click (or tap) into, in order to change how that user thinks about something.53

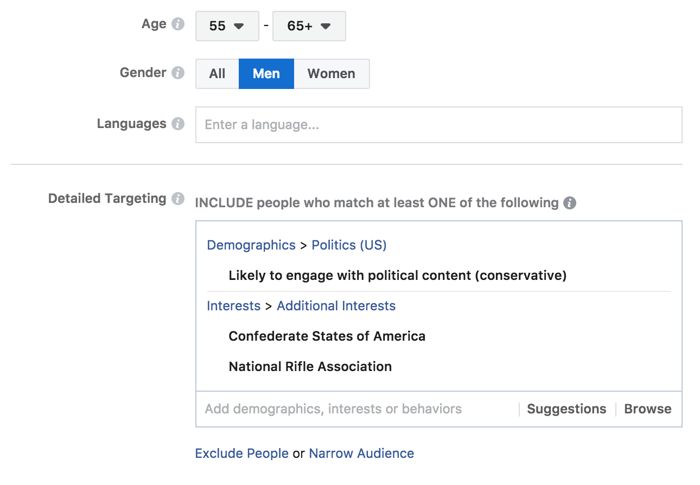

Facebook was not just instrumental in being a data pool for Cambridge Analytica. Both were enlisted by the Republican campaign in 2016 and proved to be instrumental in the persuasion of potential voters to either vote for Trump or not vote for Clinton. Facebook provided them with powerful marketing tools, which is why two million dollars of the political advertising campaign was entirely put into Facebook.54 There are many marketing tools used by advertisers to target their audience. One such tool is the Custom Audiences from Customer Lists, which is used to match the real people on the lists bought from data brokers with their Facebook profile. Another tool, Audience Targeting Options, allows ads to be targeted to people based on their Facebook activity, ethnic affinity, location and demographic, age, gender interests and so on. Another important marketing tool allows for advertisers to create what are known as dark ads. These ads are only shared with highly targeted users selected by advertisers. Dark ads give brands and publishers a way to promote content that they do not have to host on their own public profiles for everyone to see. This content is only for select members of their following or a target demographic. Each ad varies in tone, content, and form, to fit the psychographic data profile of users. This means, were you to visit the official page of, say, the Republican Party, or any other public Facebook page, you would see a version of it that is tailored to you.

Facebook was the first to develop the concept of “unpublished posts,” another name for dark ads, and has been paid to distribute these ads for years. This is not entirely new, most websites function this way. It is useful when A/B testing different content strategies, wherein you test a number of different variables on a piece of content to determine what will maximize user engagement. So for instance, when you enter Booking.com, there might be a bigger "buy" button, a different color, a different font, than shown on another day or to another user of a different demographic. The same was applied to these dark ads during the election campaign—different colors, a different font, or a different ad altogether. Some with the intent to persuade users to vote for Trump, other ads to suppress voter turnout of (Democrat) users. As mentioned previously, Facebook has published research that confirms their ability to influence voter turnout using persuasive messaging.

It is not the amount or size of the data being extracted that is crucial here, it is the inherent value produced from a set of data points relationship to other sets of data points.55 In other words, value from our personal data are not derived from one single post or status update that we write about ourselves, but rather comes from the associations which are determined by the digital traces we leave behind. This is why, even if Facebook were to aggressively police the situation, it would merely be a surface solution to the inherent problems so far discussed.

Update: Data Privacy Policy

In April 2018, Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, stood before the US Senate in a hearing about the company’s involvement in the presidential election.56 Leading up to the hearing, there had been a lot of traction around the topic of surveillance, social media echo chambers, data privacy, fake news, and so forth. Facebook also took to the media and made a series of announcements intended to demonstrate that it took the data leak seriously and was working to prevent it from happening again. The changes to be made, mentioned in these announcements and repeated by Zuckerberg in the hearing, included making privacy shortcuts easier to find, restricting the data shared with developers when you log in using your Facebook account, and labeling political ads so that anyone will be able to view all of the ads run by particular candidates by visiting their page.57 Again, these are surface level solutions. Understanding datafication—how our data is rendered actionable–is an important first step, but Facebooks revenue is generated from a form of advertising that relies on addiction and manipulation. The emergent concern from this scandal is not social media users data privacy and how Facebook can secure it. Anyone who claims to have nothing to hide is not a relevant position. It is not that this research was supposed to identify every user on an individual level from this data, but rather to develop a method and models for sorting people based on Facebook profiles. As pointed out in a recent article in The Atlantic, in developing Cambridge Analytica’s models "once the 'training set’ had been used to learn how to psychologically profile people, this specific data itself is no longer necessary. It can be applied to create databases of people from other sources—electoral rolls, data on purchasing habits or group affiliations, or anything gleaned by the hundreds of online data companies—then letting Facebook itself match those people up to their Facebook accounts. Facebook might never reveal the names in an audience to advertisers or political campaigns, but the effects are the same."58 The best system for micro-targeting ads is Facebook itself. This is why "Facebook’s market value is half a trillion dollars. In Facebook’s ad system, there are no restrictions on sending ads to people based on any 'targetable’ attribute, like older men who are interested in the 'Confederate States of America’ and the National Rifle Association and who are 'likely to engage with political content (conservative).’"59

Deadlock: The Ad Business Model

Tech companies have achieved mass-scale addiction, and the manipulation of advertising has taken on a new shape, to the extent that we can no longer call it advertising. As Lanier puts it, the key difference between advertisements seen on television or on the street, is that the commercial or the billboard is not watching you. When you are using Google search, Youtube, social media, you are being observed constantly and algorithms are taking that information and changing what you see next. These algorithms make attempts, searching for patterns that will get you to change your behavior according to how the advertiser wants you to behave.60

In line with Lanier, Shoshana Zuboff expands on the threats of the prevailing and expanding presence of Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft products and services. In an essay61 Zuboff uses the term "surveillance capitalism" to describe the surveillance marketing from the major tech companies that are compiling data on everything we do, online and offline. From this perspective, "social media is one giant surveillance apparatus where human beings are turned into pile of data that then gets manipulated, repackaged, and sold. The goal being: 'to change people’s actual behavior at scale.’" You are taking part in a mass-scale behavioral experiment, (as confirmed by Facebooks Product Management Director) whether you have a Facebook account or not.62 Whether we update our privacy policies, or find ways to regulate the content on these platforms, are not dealing with the core issue. Tech companies need incentives to create designs that are empowering rather than exploitive. In order to gain that incentive they need alternate business models63 to that of the ad business model which rely on addiction and manipulation. As Zuboff points out:

The assault on behavioral data is so sweeping that it can no longer be circumscribed by the concept of privacy and its contests. This is a different kind of challenge now, one that I am thinking of matters that include, but are not limited to, the sanctity of the individual and the ideals of social equality; the development of identity, autonomy, and moral reasoning; the integrity of contract, the freedom that accrues to the making and fulfilling of promises; norms and rules of collective agreement; the functions of market democracy; the political integrity of societies; and the future of democratic sovereignty.

The Major tech companies have attained tremendous power and influence, entering just about every area of life, and keep expanding. Amazon determines how people shop, Google how they acquire knowledge, Facebook how they communicate. All of them are making decisions about "who gets a digital megaphone and who should be unplugged from the web".64 The issue to be stressed is that they do not offer any way for us to make collective decisions about what they do and how they operate. They provide products and services predefined and packaged by the companies themselves. Facebook and Google in particular, relying on the ad business model, are most involved in manipulation. Unless they apply an alternate business model, addiction and manipulation will continue and inevitably get more sophisticated. As Foer warns:

Facebook would never put it this way, but algorithms are meant to erode free will, to relieve humans of the burden of choosing, to nudge them in the right direction. Algorithms fuel a sense of omnipotence, the condescending belief that our behavior can be altered, without our even being aware of the hand guiding us, in a superior direction. Facebook as with most tech companies, are comprised of left leaning groups, and they could end up in a situation where they can design a more perfect social world. We are the screws and rivets in the grand design.65

Who or What is Acting

There are problems on global, regional, local, and personal scales, and the world becomes more confusing and seemingly controlled by vast impersonal forces that no single individual can fully bring within view. With headlines spanning from topics of concern about big data and information privacy, surveillance, financial crises, climate change, endless war on terror, fake news, meanwhile political discourse is a performance art of fake outrage, it becomes difficult to both grasp and take action. We can through our screens, or with the push of a button, or even without bodily movements (through algorithms), create changes in various scale. But if Facebook convinces us whom to vote for at the next election, defines our social relations, and is the public place where we express freedom of speech; if Google tells us what treatment to seek when we are ill, its maps not only provides our route but also suggest a destination based on the data of our behavior which is sold to anyone who wants a piece of our behavior for profit; if YouTube’s algorithmic curation results in content where the intention and production is based on accumulating ad revenue; and smartphones, refrigerators, and public transport passes are in constant interconnection, tracking and determining our daily movements, then who or what exactly, is governing reality? How do we begin to deal with complex and planetary challenges? The size and structure of a lot of these problems dazzle and overwhelm us, but have at the same time been engineered and designed by us—technology, economical systems—and have become performative actors that plan our present from the future. How can we upgrade our ideas, concepts and actions, in order to stop following into a prescribed direction, being swallowed up by a process without understanding how it works and how we influence it?

PART THREE: Proposing Antidotes

Approaches in Art and Design

We have now discussed technology and the individual in terms of a consumer ethic. The preliminary position was that the process of becoming an individual is a continual process and is dependent on acquiring skills and gaining competence. The way in which we do so, is through and with technology. And so it follows that in order to gain competence and skill, the relationship between humans and technology needs to be a collaborative and reciprocal one. The following will propose design methodologies and an educational method which in combination are valuable efforts in establishing this relation, and in undermining the dominant design of technology that places the designer/creator at one end, and the user/consumer at the other. There are two approaches in art and design: speculative art and design, and hacking and open design. Wherein Speculative art and design offer a space for reflection, and hacking and open design having qualities of share-ability, comprehensibility, alterability and offer various entry points to technological engagement through which theoretical understanding can emerge.

Speculative Art and Design

By placing new technological developments within imaginary but believable everyday situations, speculative art and design projects allow us to debate the implications of different technological futures before they happen. Through such projects, it is possible to critically reflect on the development and role of technological objects and systems in society. Returning to the art piece by Antonia Hirsch mentioned in the preface—beholding touchscreen devices out of its usual context, lead to reflecting and questioning the emotional bond humans feel towards handheld devices. Why is it that dominant design of technical objects are sleek, shiny, and closed, fostering a fetishistic relationship?66 Moreover, it led to investigating how design influences the relationship we have with technology. In a similar way, speculative art and design offers a space for critical reflection.

Speculative design ideas, ideals, and approaches, take form in fields of design, architecture, cinema, photography and fine art, spanning from political theory, philosophy of technology, literary fiction and surely more. The following examples will focus on Kim Laughton's’ digital rendering artwork which often depicts a merging of consumer products, technological fetishism, image production and labor, and Bruce Sterling’s design concept of Spimes which speculate on the future of more preferable and sustainable technological products.

Self-Reflective Digital Art

Kim Laughton’s artworks are images of a near future. In his digital rendering artwork, he encourages a discussion about the power of technologies and images. His CGI videos are often reflective on the creation of images using CGI software,67 that is to say, the videos are self-reflective68. He demonstrates that these seductive digital surfaces have greater potential of layered meaning69 when they fall apart, revealing their construction when in the hands of the human and the computer. There is often something bizarre and uncanny,70 and at the same time oddly comforting and familiar71 in his digital images. And sometimes you are almost made to think you are really just looking at an ad gone awry.72

Speculative Design System of Technological Products

Unlike Kim Laughton’s artwork which draw on the emotions of the viewer, Bruce Sterling’s speculative concept is a diegetic prototype—a system that speculates on a future of more preferable and sustainable technological products. In “Shaping Things” he laid out this speculative design system through the concept of Spimes. A Spime is a location-aware, environment-aware, self-logging, self-documenting, uniquely identified object that transmits data about itself and its environment to a system. So what constitutes a Spime and how would this system work? You would first encounter the Spime as a virtual image while searching on a website. This image would be linked with three-dimensional computer-designed engineering specifications of the object. It would include material specifications, engineering tolerances, and so on. This object would not exist until you legally guarantee that you want it—by purchasing it. Your account information would be embedded in that transaction and it would be integrated into your Spime management inventory system. Upon delivery you have the object’s unique ID code, consisting of information about its material, ownership history, geographical tracking to establish its position in space and time, and other information that could contribute to any modification of the object. At the end of its lifespan, it is deactivated, disassembled, and put back into the manufacturing stream. And its data would remain available for historical analysis.

This diegetic prototype is a source for thinking of how sustainable and manufactured object might look like and how it could work in a system, as opposed to the disposable products that currently permeate our society causing havoc to the global climate system. Since 2003, when Sterling’s "Shaping Things" was first published, there have been some real world initiatives in this area. They include Cisco, IP For Smart Objects Alliance, but also larger firms like IBM, Nokia, and Microsoft have been working on what are called smart networks.73 There have also been smaller startups such as Touchatag and Openspime which are directly inspired by Sterling’s theory. Fundamentally his theory tackles the critical issue of recycling, making it possible to begin thinking about the greenhouse effect, which is the problem of the abundance of trash. As stressed by Sterling himself, his theory is not a flawless prototype meant to be universally applied. Rather, because a theory has flaws, it is a source to invent possible outcomes and reflect on them. For instance, reflecting on what the possible downsides of location-aware, self-identifying, always-on devices, will inevitably lead to that of privacy concerns—"there are a lot of socio-political functional personal reasons to be suspicious of how tracking might be (mis)used both by individuals and by governments. It is already a rapidly advancing technology with dark sides. From a company providing technology to spy on ones employees or ones spouse and children, to governments or corporations surveilling your online activity and possibly prosecuting you based on the data."74 We need such theories to be able to imagine and start co-creating possible futures, and in the process of doing so, reflect on what we are doing.

Hacking: A Reciprocal Form of Interaction

The way in which the practice of hacking is understood in this text, is that it serves to undermine and dismantle current design of technology. "Hacking is about overcoming the limitations of an existing object, service or system which was set for one purpose, and finding an access point, intellectually or physically, where its original function can be expanded, altered, or improved to serve a new purpose or solve a problem."75 It is the will to re-purpose existing designs of systems or objects in ways more precisely tailored to how you want to use it. It merges rather than separates design and people, and yields benefits in the process. This merging fosters a different type of engagement between the product and the user, and reciprocity between the user and the designer. As stressed throughout this text, the dominant model for design has placed the designer/creator at one end, and the consumer at the other. Hack design serves as a process that facilitates the ingenuity to expand the potential of what has been created, by enabling the end user to be part of the process, and not only on the receiving end of it. This approach result in designs that often give the impression that the object or system is unfinished—something that is in process. It may therefore be unstable as it is presented. Hack design is an approach that enables alterations that are inevitably variable in outcome. It also bears the possibility of improving the skill and competence of whomever should engage with the object or system. How would you for instance go about tailoring Facebook to your own needs and interest? Knowing how the News Feed is designed to keep you scrolling, engaging in a mindless activity, how could you prevent yourself from engaging in the pattern of behavior it induces? Hacking would be an approach to intervene in its design and alter its purpose.

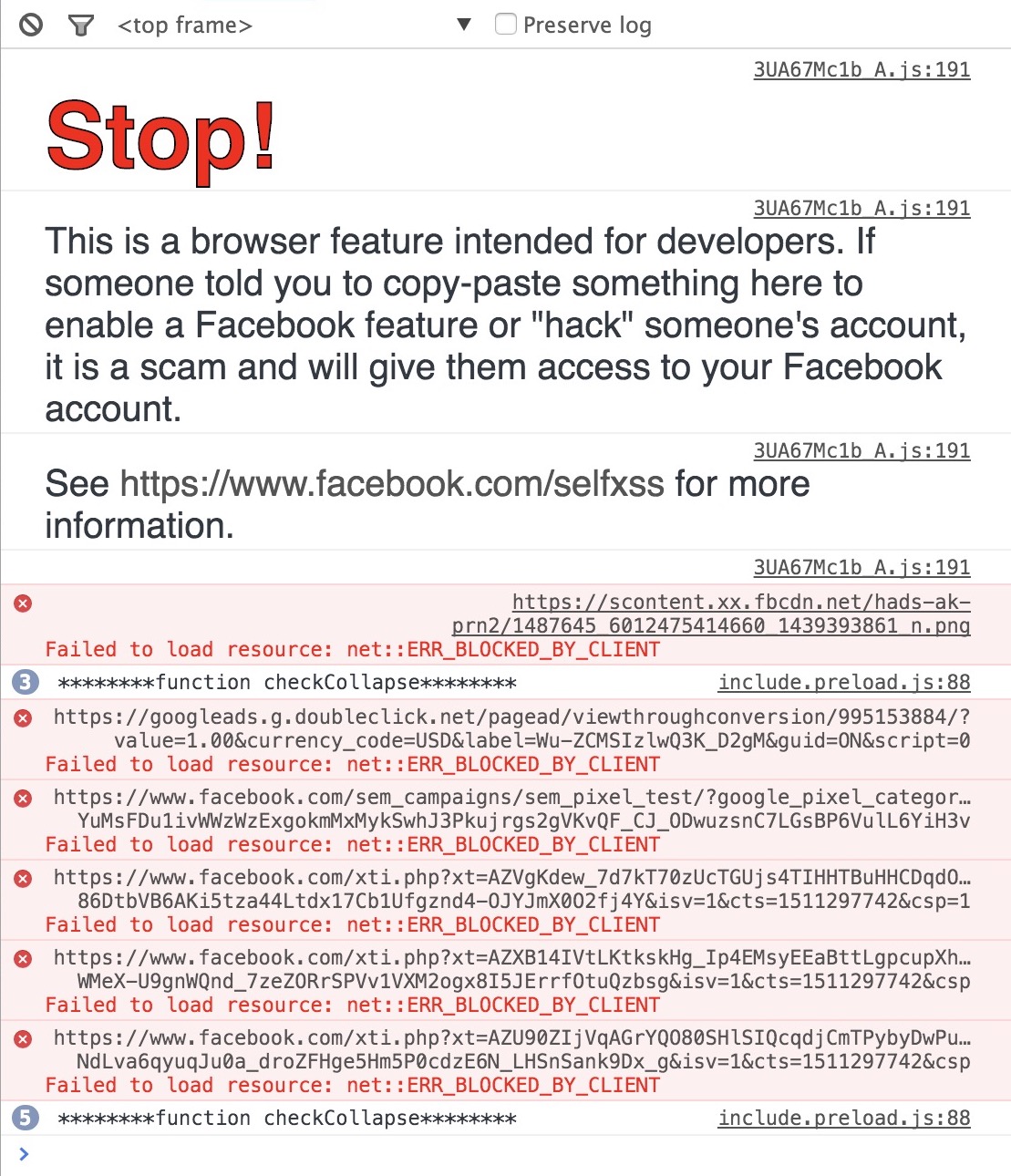

In early 2017, I sought to do exactly that. Based on the common experience of logging in to Facebook having something specific to check, only to find yourself mindlessly scrolling an hour later, I started a project with the aim to reveal the intent of the habit-forming design of the News Feed. Seeing as Facebook does not provide an enable/disable feature for your News Feed, the option was to hack Facebook through the web browser. The aim was to make the user not only aware of the mindless activity is due to its design, but also to prevent the habit. Together with Kees van Drongelen76, I developed a browser extension77 that makes your Facebook News Feed disappear. Only upon scrolling hastily and constantly does the feed appear, and once you stop scrolling the feed disappears again. This hack design was to make obvious that the intention of the News Feed is to keep you scrolling rather than browse meaningful content.

Open Design: Take, Alter, Transform, Redistribute

Open design are designs which invite hacking. Qualifications of open design are open-source, comprehensible, alterable, constructible. These qualifications will be elaborated on in terms of software development. Note though, that open design is not limited to immaterial production, as the same method of production that has come to dominate the world of open source software and freely available (often user-generated) content on the internet, also extends to designing and making material things.78 Essentially open design79 is about the concept of sharing. This means the user can take what is given, make alterations according to their needs, transform it and redistribute it to others. The implications of open source—a material ontology of sharing practices, therefore strongly bears a social dimension.

Sharing (open-source) code is a relatively recent form of cultural sharing. Sharing is part of how a community operates within any field that creates media. Steve lambert,80 explains how we are familiar with…

The image of scientists working in labs, researching, generating and testing hypotheses, then publishing their work in journals or otherwise presenting their work to the scientific community. As an analogy, this method of researching and publishing extends to writers, performers, musicians, software developers, and anyone else who creates media. Extending this analogy, repeating the research someone else has done is redundant. The goal of publishing research outcomes is to make progress. This can only happen if the work is documented so that theories, techniques, and knowledge can be built upon. Through this process, scientific theories are established, art movements emerge, musical styles develop into new styles, software becomes more sophisticated. Knowledge is collected and developed, and progress is made over generations. This is why we share our research.81

For software, open design means that the result is not a product, but a project.

The Free Software Movement

The Free Software Movement82 emerged in the early 1980s in response to efforts to withhold software program source code to increase profit, such as non-disclosure agreements and the patenting of software concepts. Richard Stallman, the founder of Free Software Movement, created Four Freedoms of what constitutes a free software:

Freedom 0: You are free to run the program, for any purpose.

Freedom 1: You are free to study how the program works, and adapt it to your needs. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

Freedom 2: You are free to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor.

Freedom 3: You are free to improve the program, and release your improvements to the public so that the whole community benefits.

Well-known examples of programs that meet all freedoms include the Linux operating system, the Apache Web Server, Mozilla Firefox web browser, and the web publishing software WordPress. In a case study, Steve lambert held up Adobe Photoshop against these Four Freedoms83 to examine the implications of not meeting the qualifications:

Freedom 0: Are we free to use Photoshop for any purpose? Sure, we can use Photoshop to make everything from a corporate presentation to pornography.

Freedom 1: Are we free to study the program and adapt it to our needs? In one way, yes, we can get an Adobe Photoshop manual and learn how the program works, and we can customize the workspace and write Photoshop Actions to script the program and adapt it to our needs. But, these are relatively insignificant changes. The source code is not publicly available and we cannot adapt the software by changing the source code, so thereby Photoshop fails to meet this freedom.

Freedom 2: Can we redistribute copies of Photoshop to help our neighbors? While that may be how some people obtain copies of the program, technically this is a violation of the user license, and therefore illegal. The third freedom is violated.

Freedom 3: Can I make improvements to Photoshop and release, or even sell, the Photoshop “Steve Lambert Edition” for the benefit of Photoshop users? No, absolutely not. This freedom is also violated.

Adobe’s model is based on selling licenses of their software. Each license (copy of the software) has to be bought. For innovation, one could argue that Adobe creates quality products and is certainly an industry leader. But we are not free to improve their work, we are not free to examine it, and we are not free to distribute it. What if Adobe were to stop supporting or releasing one of the programs they currently distribute? Their code remains inaccessible. Unlike the case of WordPress—a project that would never have come about if the abandoned project b2cafelog, from which WordPress was developed, had been licensed with a proprietary license.84

Open Design Software: Mozilla Firefox

Let's turn to the open design software Mozilla Firefox web browser. You do not have to purchase it, you are free to build on it by contributing core code, or through extensions and add-ons (sub-programs that extend the browsers functionality), or creating Firefox software offshoots like CELTX. This makes Mozilla Firefox a project, not a product. You can alter it by adding existing plug-ins which are themselves projects, you can build a plug-in (in collaboration with others), or you can make larger alterations by working on the source-code. Going from user, to designer, to programmer, of course requires interdisciplinary skill sets, but it is nevertheless not inaccessible. And the user is not merely a consumer, as making small low-skill alterations using plug-ins or making large high-skill alterations by tinkering the source-code, are not only possible but encouraged. On the Mozilla blog there are posts documenting ways to hack Mozilla Firefox.85 These hacks include plug-ins and add-ons, new developer editions, etc. And their source code is available on the software development platform GitHub86, where anyone can file issues or design requests. Notice in the project example given previously of hacking Facebook through a browser extension, when tempering with the existing code using the Page Inspector tool, not only did Facebook developers make it cumbersome, but also prompted a warning message87 from which you are implicitly made to feel you are doing something malicious or suspicious. That is because Facebook is a product, not a project. But if it were, then it would likely not resemble its current state. It would take on a different form and in turn we could perhaps begin to change the presuppositions of Facebook which defines the individual, social relations, identity, and how it is expressed.

An Educational Method

In a series of workshops88 involving technological engagement, two researchers at King’s College London, aimed to rethink the contested relationship between humans and technology. The workshops brought together interdisciplinary participants (hackers and non-hackers) to increase understanding of the "socio-cultural and political-economic dimensions of datafication".89 They did so by exploring smartphone apps as technical objects, to better understand their social and cultural dimensions. In so doing, the workshops aimed to augment critical and creative agency, and on a practical level exceed the normative utility of the data smartphone users generate. The following will be a summary of their report90 and then an analysis in terms of its potential as a method that facilitates gaining agency, and in terms of Simondon, facilitates individuation.

During the workshops, apps were decompiled and its source code examined, revealing permissions written into the software that regularly captures and facilitates the flows of data to third parties and data brokers. They used various tools91 which allowed them to move apps from smartphones onto laptops for closer examination; to render the computer-readable code that programs the apps into more human-readable Java; and to capture and analyze data flows—the normally hidden traffic between apps and servers. Through these tools the participants were able to see and experience the direct movement of personal data. Through engagement with the materiality of these technical objects, demystifying the otherwise inaccessible datafication process, it not only enabled those with more advanced technical skills to modify the application to their particular needs, but it also created a space for social and cultural critique. For example, by decompiling the Facebook Messenger app, participants were able to make visible the permission-based security files that governs data flows in and through the app. During this procedure they identified 40 different permissions wherein the developer of the app coded legal means for gathering data from its users. One significant permission of the app stated that if the user is logged in and sends an MMS message from their smartphone, it can read all of the user’s texts. Other permissions stated that the app can send SMS messages without the user’s confirmation, and that the camera can collect images that it is seeing at anytime. What these findings elucidate is that the many invasive permissions written in the code are much more comprehensible and straightforward than the terms and conditions of the app. In other words, how the app is used, is made more clear to third parties than it is to the user of the app. Subsequent questions that follow these findings is: (1) how might we interact with our apps differently if we had direct access to these permissions? (2) how might we hack the apps to serve the interest of the user rather than third parties?

Through this type of collective technical engagement, skills and competence on practical and theoretical levels are developed, and new perspectives on the social and political dimensions of technology are gained. Drawing from the hacker ethos of technological engagement, these series of workshops have both creative and critical potential. As a method, not only does it demonstrate how theoretical understanding emerges through and from practical engagement, but it also functions as a intermediary between the participants and as a space for collaboration. That is to say it acts as a space for translation—through different levels in participant skill sets, areas of expertise, and technical capacities. As the researchers that organized these workshops explains, "we had to observe and learn about hacking practices so we could meaningfully communicate with coders, programmers and hackers. In working through these interdisciplinary translation issues, myriad possibilities oriented around rethinking and re-articulating social and political theory arose through the different ways in which we could engage the technology itself."92 In this way the workshop exemplifies what Simondon called transduction—through the articulation of the technical, socio-cultural and political economic, between interdisciplinary participants, making possible for individuation and trans-individuation to occur.