0. ABSTRACT

It is way more important to look for what you do not know, rather than searching for what you already know. In order to do that, some undefined space at the starting point is necessary. I noticed that whenever I stop looking specifically for the answer to the question that I asked myself, I would discover things that I would have never found otherwise. These random encounters with ideas and new discoveries, were in fact caused by not doing what was intended.

I had this question on my mind: how can we creatively profit from doing nothing? Is it possible to gain something from plain time-wasting? How is it possible that we find more when we do not look for it? Does it happen because when we do ‘nothing’ we are also less serious, because there is nothing to be concerned about? This problem is my research subject.

I was concerned if there would be enough time to look for the answers. However, there was even more time required for determining what should be the question (and upon finding the answer I also found the question). At some point of my research into the subject of play this question became the question that could be used for defining the starting point for my thesis. Can we profit from doing nothing as designers?

I analyse playfulness (as a possible contrary of seriousness) and the ways it can broaden the possibilities of creativity. How does the economy of time in the society that we live in influence us? Is everything transformed into waiting? On the given examples I show how important it is to take the time to ‘stop doing’.

When faced with boredom we seek out for a solution to stop that feeling immediately. Boredom is unwelcome. However, it turns out that boredom has a value of its own, that we might find more fruitful than expected.

For the most part, I could not make my thesis if I was not playing. Through play I was able to construct a certain way of relating to information.

In my thesis, the reader can make himself familiar with the instructions on how to proceed with the manner of reading. Replacing introduction with instructions may offer possibility for more engaging reading experience, because the reader is not preconditioned about what he is going to experience, but instead he can explore the content according to his own engagement with the rules. Through these means I am exploring the notion of playfulness in creating one’s own rules. In the end a platform for reading is like a platform for thought, and reading is fast guessing.1

Therefore reading can be interpreted as a game to perform with oneself. Depending on the track you followed the result is different.

8. CONCLUSION

As we become dependent on machines through our seated-at-the-desk work, we should reach out for a counter-action. Recreation time can be beneficial as a physical activity, for research and a time when one can commit to the exploration of a new field of work. Can freedom create rules?

Doing nothing as opposed to planned and rule driven work environment can serve as time dedicated for self-improvement. Play and improvisation become a laboratory for new ways of thinking. Therefore, we should unlearn our urge to occupy ourselves with tasks constantly and instead learn to waste more time.

Game is a creative act that allows for reinterpretation of reality, and expands the possibilities of what can be done. We can profit from that experience when we bring it back to the ‘real world’.

Play offers an opportunity of a parallel perception where our actions have less or no consequences. Engaging in the rules of a game opens new possibilities that are not available in the ‘regular’ reality. Similar occurrence can be illustrated through the modus of an art happening. During the year 2015, there was a monthly announcement on the Stedelijk (Amsterdam) website stating that a performance by Tino Seghal is taking place in the gallery.1 The viewer would wander around the space looking for this event, questioning all the encountered situations. Is this the performance or just a regular happening?

It can be said, that if there was only the announcement about the art performance without the action itself happening, that this could stand on its own as an artwork. Even if it means the artist did nothing and the viewer did not look at anything in particular. Assuming that some people knew about the performance taking place but didn’t find it they still participated in the game. This social engagement in questioning the rules of ‘normality’ applies as well to the visitors that did not know about the artwork being displayed. Time and time again the experience would be different, as well as the location so in order to witness the whole variety of possibilities a visitor had to spend time on his part to experience the happening.

When it comes to searching it is worth to remember that doing nothing will result in finding many worthwhile things.

“The revealing of things is, in fact, always dependent upon other things being simultaneously concealed (in much the same way as seeing something in one way depends on not seeing it in another). Truth is thus understood as the unconcealment that allows things to appear, and that also makes possible the truth and falsity of individual statements, and yet which arises on the basis of the ongoing play between unconcealment and concealment—a play that, for the most part, remains itself hidden and is never capable of complete elucidation. (...) It is this sense of truth as the emergence of things into unconcealment that occurs on the basis of the play between concealing and unconcealing that is taken by Heidegger as the essence (or ‘origin’) of the work of art.” 1

1. STARTING POINT

Instead of wandering outside, we might be forced to just wander in our minds instead. How does society let the time pass for us? Is everything transformed into waiting? Is a designer trapped in increasingly accelerating work dynamics? If so, should we consider a form of counter-action to the constant waiting for a new assignment, for a new answer and for a new contract routine?

It is increasingly difficult to do nothing, as we are forced to be ‘on-hold’ to face the modern rush. The most common answer to the question: “What did you do yesterday?” might be “I went to work”. In order to avoid being trapped in such a mindset, the freedom to being able to take time off and play in an alternate (self-created) version of reality is a necessary tool.

What could be the creative value of playing games? Improvised rules created in free-time, under ‘playground’ conditions, serve as an exercise in expanding one’s creative potential. Those self-driven constrictions offer possibilities for systematic work as a graphic designer. But, how can we explore this potential in the work environment?

How fast or slow time passes while we wait for things to happen defines the nature of the society we live in.

Is it becoming more difficult to not do anything?

2. GETTING BORED

There exists a saying that intelligent people do not get bored. I did hear that sentence often, when I was a child. Which sometimes made me feel like I should not have allowed myself to get to such a point of boredom. This saying is most often said by parents when they lack the time to amuse their children. But not doing anything can be defined otherwise, rather than just as boredom. The general tendency, when we start getting bored, is to feel the urge to get creative in order to escape the feeling of a lack of purpose.

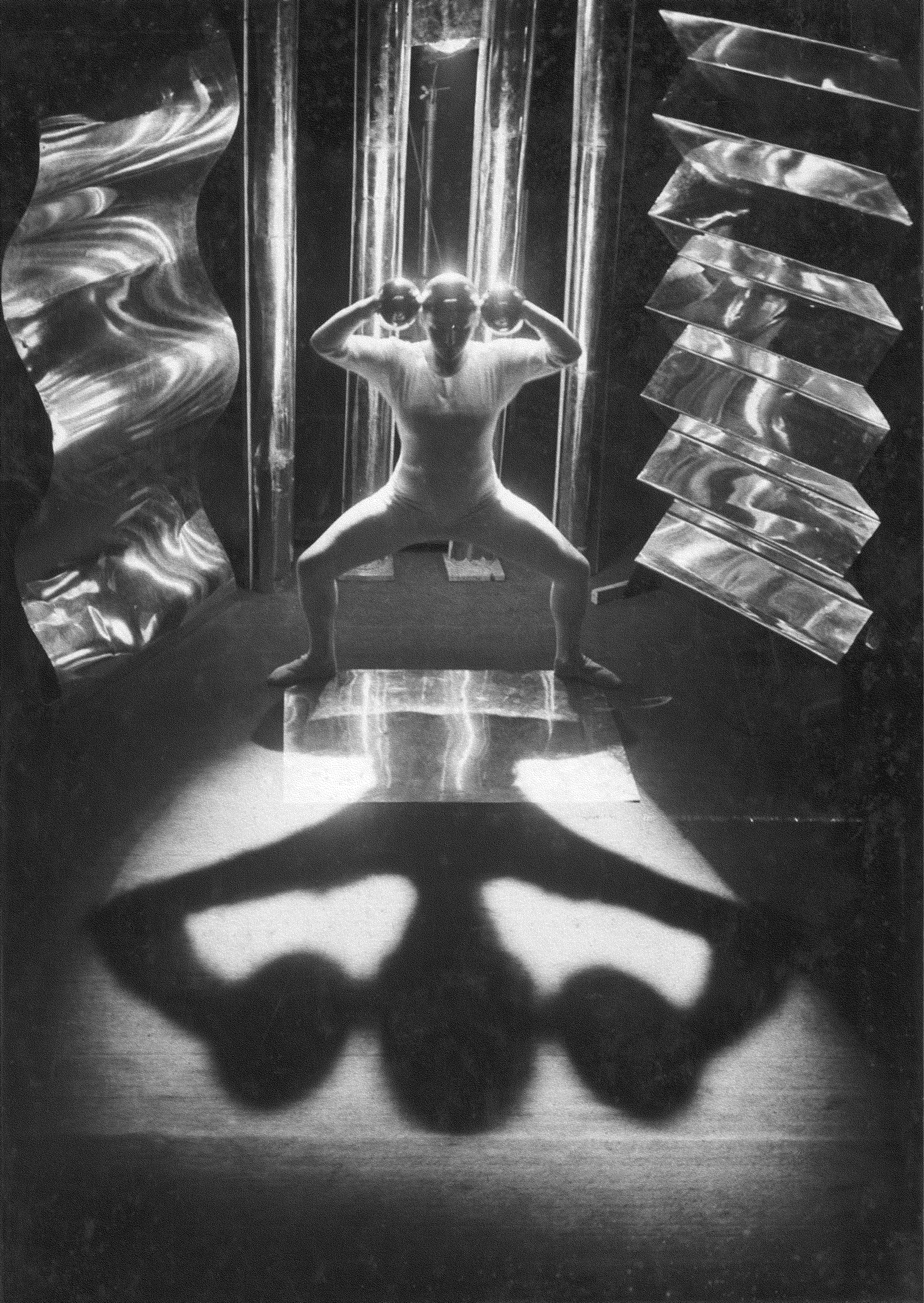

Intelligence is not only about the possession of knowledge, but also about inventiveness. The ability to create an engaging task (or a game) for oneself, when there is nothing else to do, saves a creative mind from boredom. This can be described as taking the time for mind-wandering to eventually come up with new ideas. Similar exercise in taking time for exploring the body and mind, was part of the modernist vision for education that resulted in Bauhaus going down in history as one of the most relevant creative environments.

[Fig. 04]

On the other hand, one might also say that high intelligence requires a constant supply of stimuli, in which case boredom is the least welcome experience. Because an active mind needs continual change in order to be satisfied, it is more likely to get bored relatively fast with only one task to do. The solution to such problem, according to Søren Kierkegaard, is the ‘rotation method’. He elaborated on this concept in the 1843 work Either/Or: A Fragment of Life.1 Following the line of argumentation of this Danish philosopher, in order to avoid boredom, a constant shifting between tasks is necessary. In this manner, if Karel Martens makes one layer of one print every day, he would suffer perpetual misery waiting for his single print to dry each time. Instead, we can assume he has more prints on the go that he can work on in turn. In the given example, that method alone should provide the artist with a constant satisfaction from his work. For everyone else, the result of such approach would theoretically be, the provision of more or less everlasting satisfaction derived from their actions. Without a doubt, a high level of proficiency in creativity is necessary for such scattered inventiveness.

The individual seeking this kind of satisfactory life is referred to as an aesthete “a person who professes a special or superior appreciation of what is beautiful, from Greek aisthētḗs.” 2

I — I hardly know, sir, just at present — at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then. 1

Just as the land should be left fallow at certain times in order to remain fertile, not doing anything at all can also be profitable. Nonetheless, the aesthete should be constantly switching from one task to another, and continue to change himself constantly. This anti-boredom (or possibly anti-burnout) method can be applied as a hedonistic tool in gaining satisfaction from the ‘aesthetic’ way of life. However, this repetitive search for novel, ultimately leads to a state of despair. As a result, the aesthete (the creative mind) might face the impossibility of commitment to one thing — since commitment requires repetition of one activity.

Kierkegaard elaborates further on boredom as emptiness. Concluding, that boredom is not the absence of stimulation, but the absence of meaning. Furthermore, all activities no matter how often changed from one to another, will cease being captivating at some point. Eventually the boredom ‘avoidant’ person will say: “I don’t feel like doing anything. I don’t feel like riding — the motion is too powerful; I don’t feel like walking — it is too tiring; I don’t feel like lying down, for either I have to stay down, and I don’t feel like doing that or I would have to get up again, and I don’t feel like doing that, either. Summa Summarum: I don’t feel like doing anything.” 1 Although threatened by the imminent possibility of ending, this approach could be an attempt to experience a more meaningful life. 2

Nowadays, the problem of overstimulation along with simultaneous existential boredom is valid more than ever. As a result, we might find ourselves looking for quality boredom that could improve our

life, while at the same time ‘bored to death’ by repetitive, limiting tasks at work.

3. DO YOU SEE WHAT YOU WALK PAST EVERY DAY?

René Redzepi is a Danish chef of Hungarian origin, and co-owner of Noma, a two Michelin star restaurant in Copenhagen which was given the best restaurant in the world award three years in a row from 2010 to 2012, an then again in 2014.

His idea was to reinvent Nordic cuisine through what can be characterized by locality, re-definition and clean taste. In his journal 1 published in 2011, he explores the thread that connects the kitchen’s best ideas. He analyses what are the shifts and discoveries of creativity: how does the space influence us, is everything

intuition and if real creativity happens when we play or only in the moments of despair.

At the Noma premises in Copenhagen’s harbour area, there are periods of not-doing usual work — which can be devoted to anything from picking up grass in the field to burning tree bark. The 60 members of staff, not just the chefs, are encouraged at these times to look for new ingredients.2 Despite the extremely demanding work routine, all the staff members are welcome to create their own dish proposals and develop their own ideas independently. During Saturday’s late evenings everyone meet to (literally) taste each other’s ideas. Unlike other chefs Redzepi encourages everyone to save their ideas for themselves, for their own development as culinary creatives. Despite the almost ever lasting cold Scandinavia weather, unforgiving for an plant that happens to sprout too early, the entire concept of the restaurant is based on the idea of locality. So walks to work and biking through the woods, result in new discoveries that enrich the palette of this cutting-edge kitchen. [Fig. 08] This is an approach that celebrates time, which applies to other aspects of the kitchen like the re-discovery of existing ingredients by putting them through different methods such as fermentation. Not to mention the restaurant’s leitmotif — the ‘here and now in time and place’. Redzepi says that “as a cook you are creating a language, we need an alphabet to build sentences, the ingredients are our alphabet. And the more letters we have, the more beautiful the prose.” 3 Time is an ingredient, enriching the creative tools and making space for discoveries. These tools allow for re-exploring the world anew.

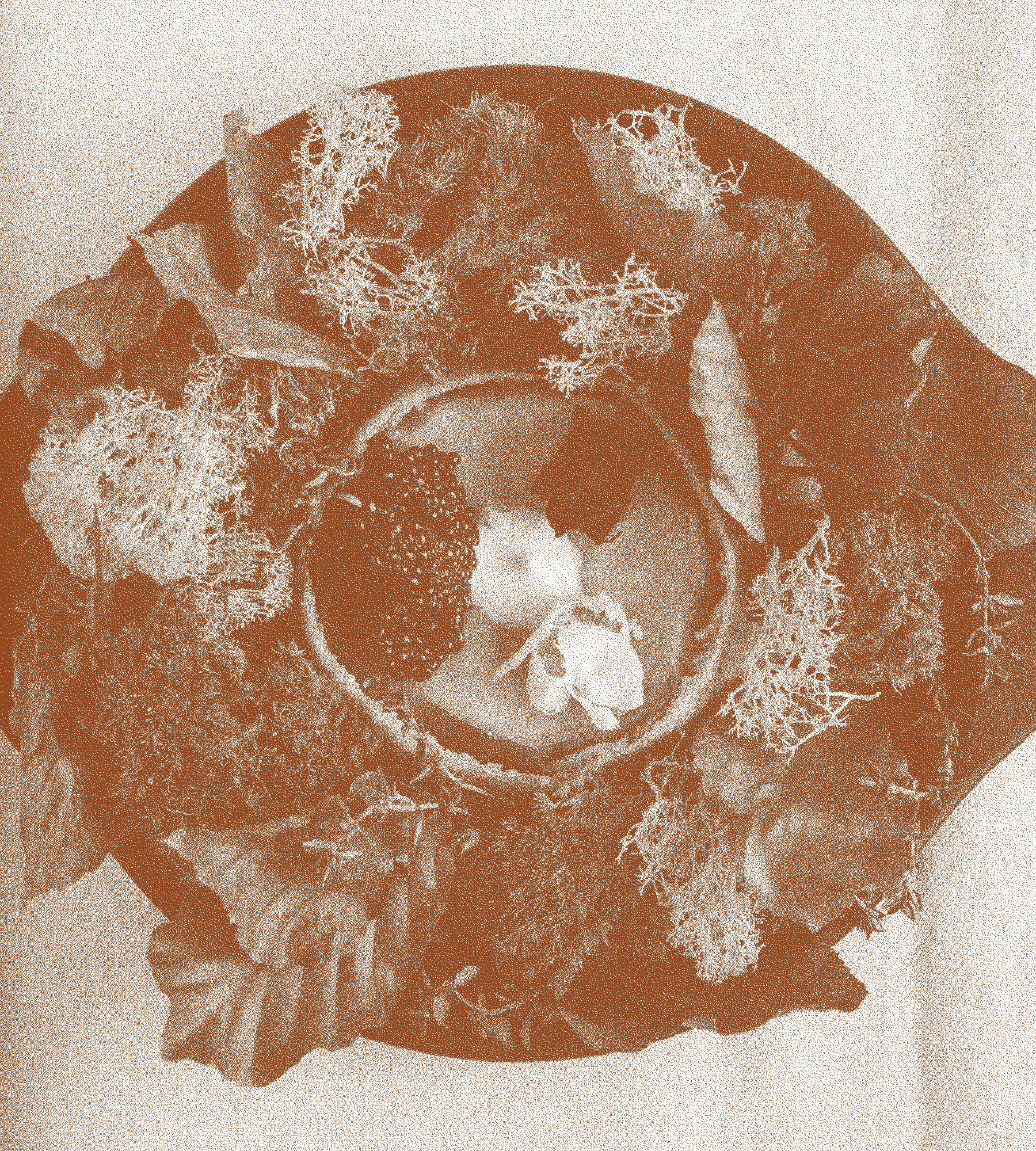

Such rediscovery of the already known surroundings can happen when one dedicates time for it. However obvious it might sound, a lot of commitment is necessary if one wants to find something new. In the spring of 2004 a Swedish forager contacted the restaurant. It turned out that while people in this region of Scandinavia had been importing walnuts for decades, similar or even better ingredients were just ten minutes outside of Copenhagen.4 Not only tastes mimicking the so far imported ingredients were found, but also new marvels in always-present in this area trees, grasses and mosses. An old Swedish army survival book provided background information about the multitude of available edibles. This seemingly redundant book was a revelation on how little was noticed, when passing by it every day. Such shift in the way of seeing resulted in questioning everything and rethinking the approach to food.

The given example illustrates how a strong identity can be created by taking a step back (and around) instead of only moving forward. For Noma this moment of realisation of the richness of their surroundings was a keystone in creating their distinct identity. [Fig. 09] In other words, the recipe for a rediscovery is sometimes lost or forgotten knowledge that needs to be reconstructed. The next step is made by walking around and collecting the lost pieces. Eventually they can be put together in an entirely new way.

4. HOW CAN I GET FROM HERE TO THERE?

You are walking around in a hurry when all of a sudden you are stopped by a random passer-by on the street. Relying on your knowledge, he asks you how to get somewhere. Upon giving an answer you question yourself — is this (for sure) the way to get there? The passer-by walks away with the description that you provided. You are then left wondering if you were right or wrong.

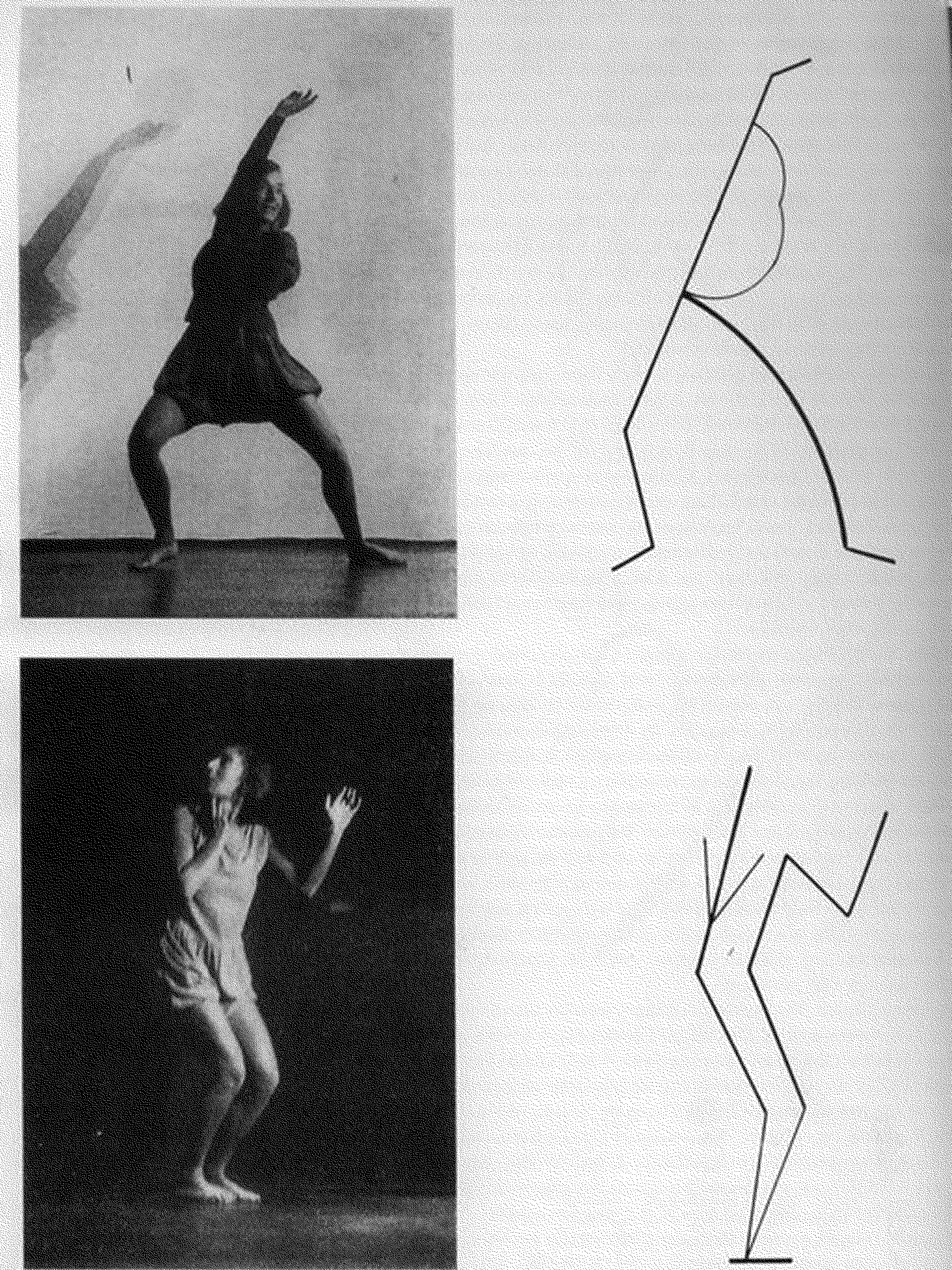

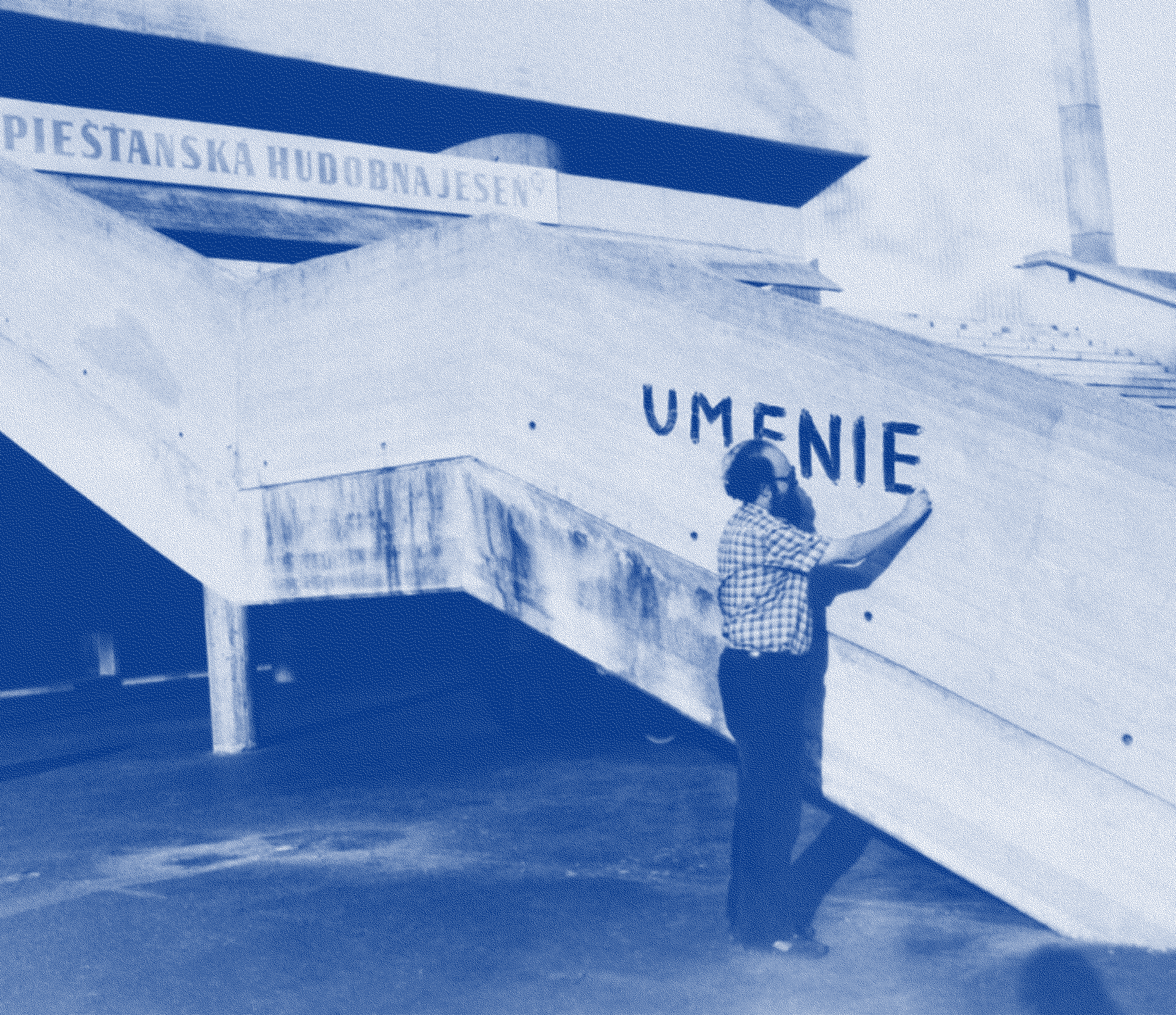

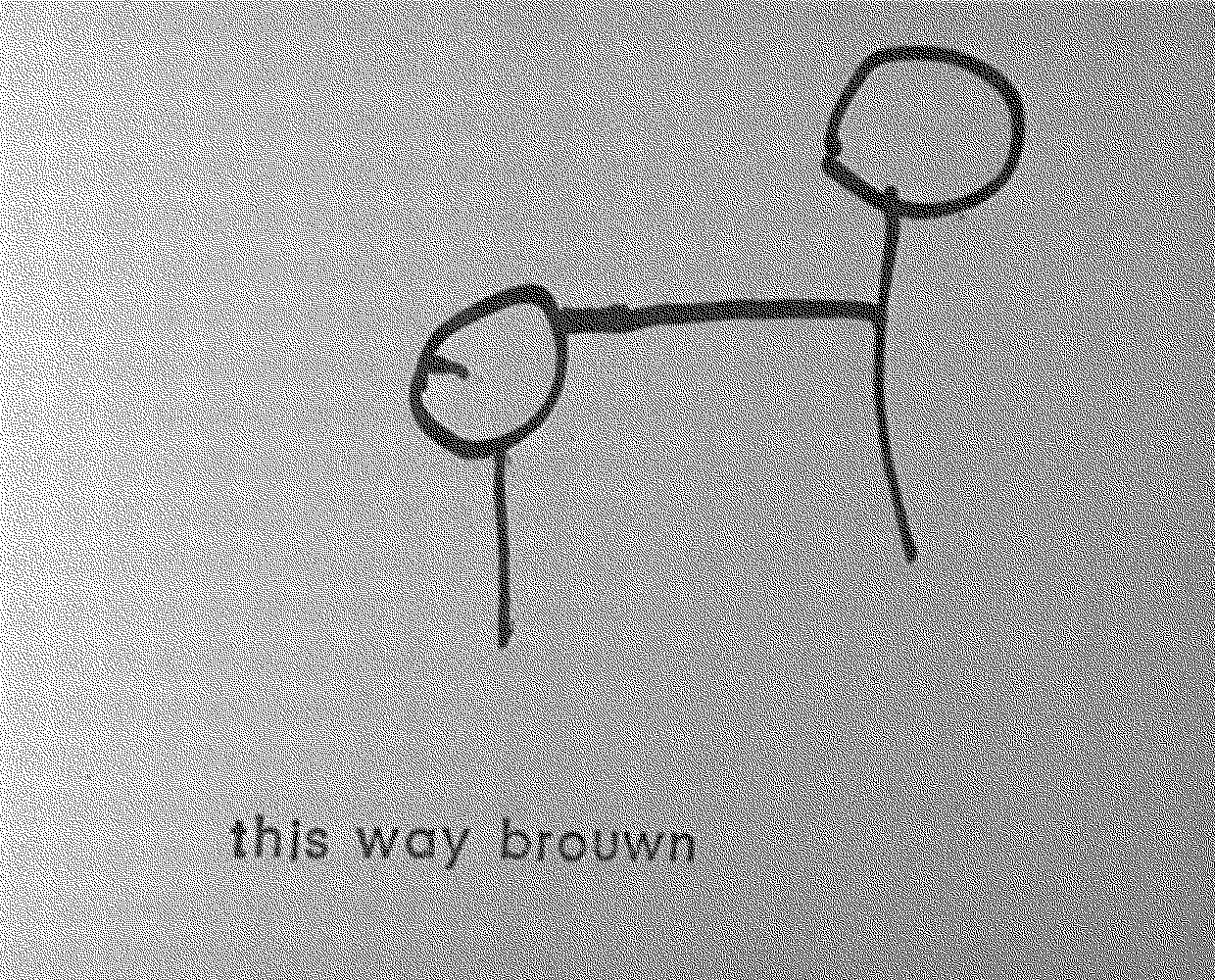

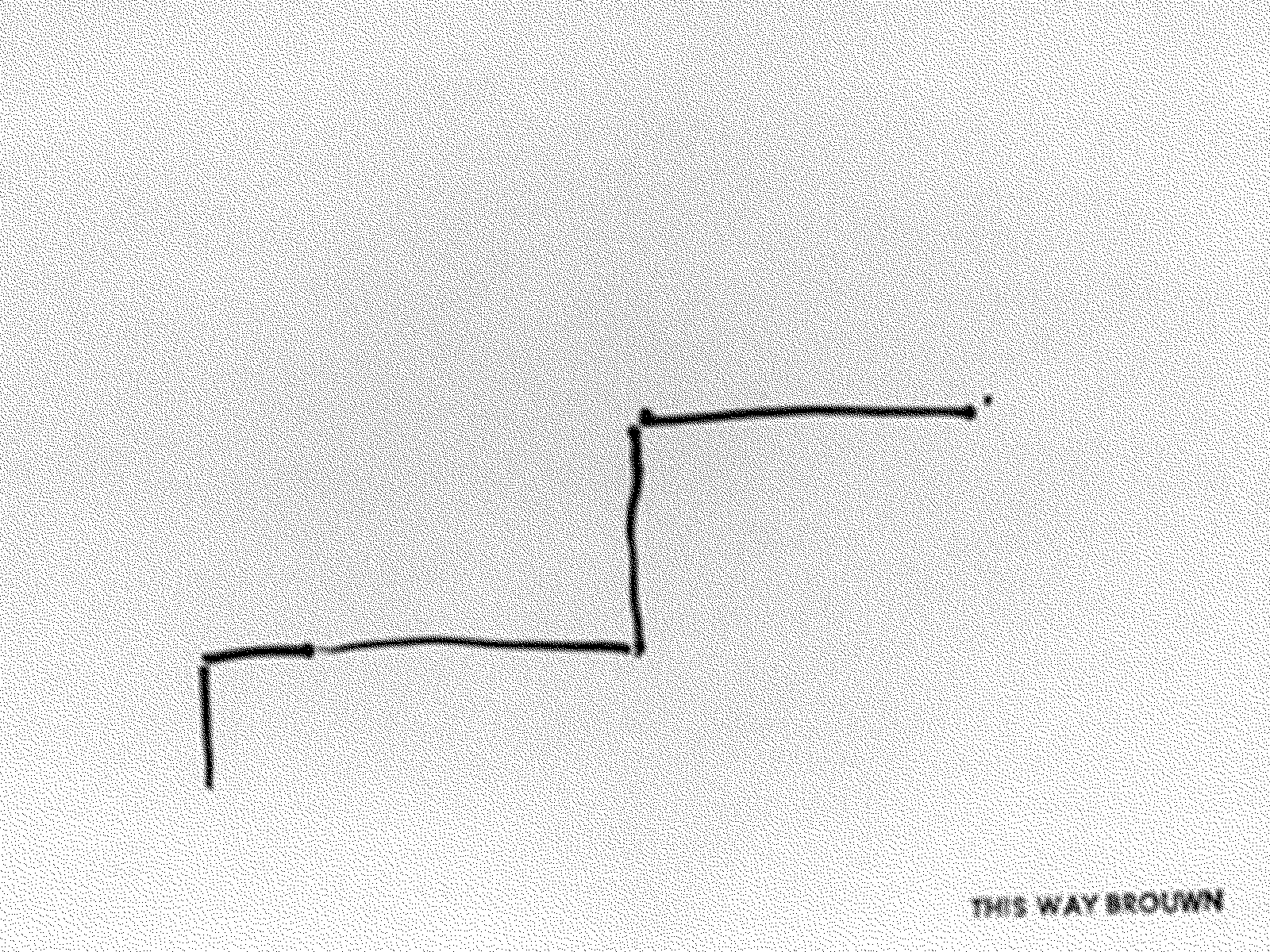

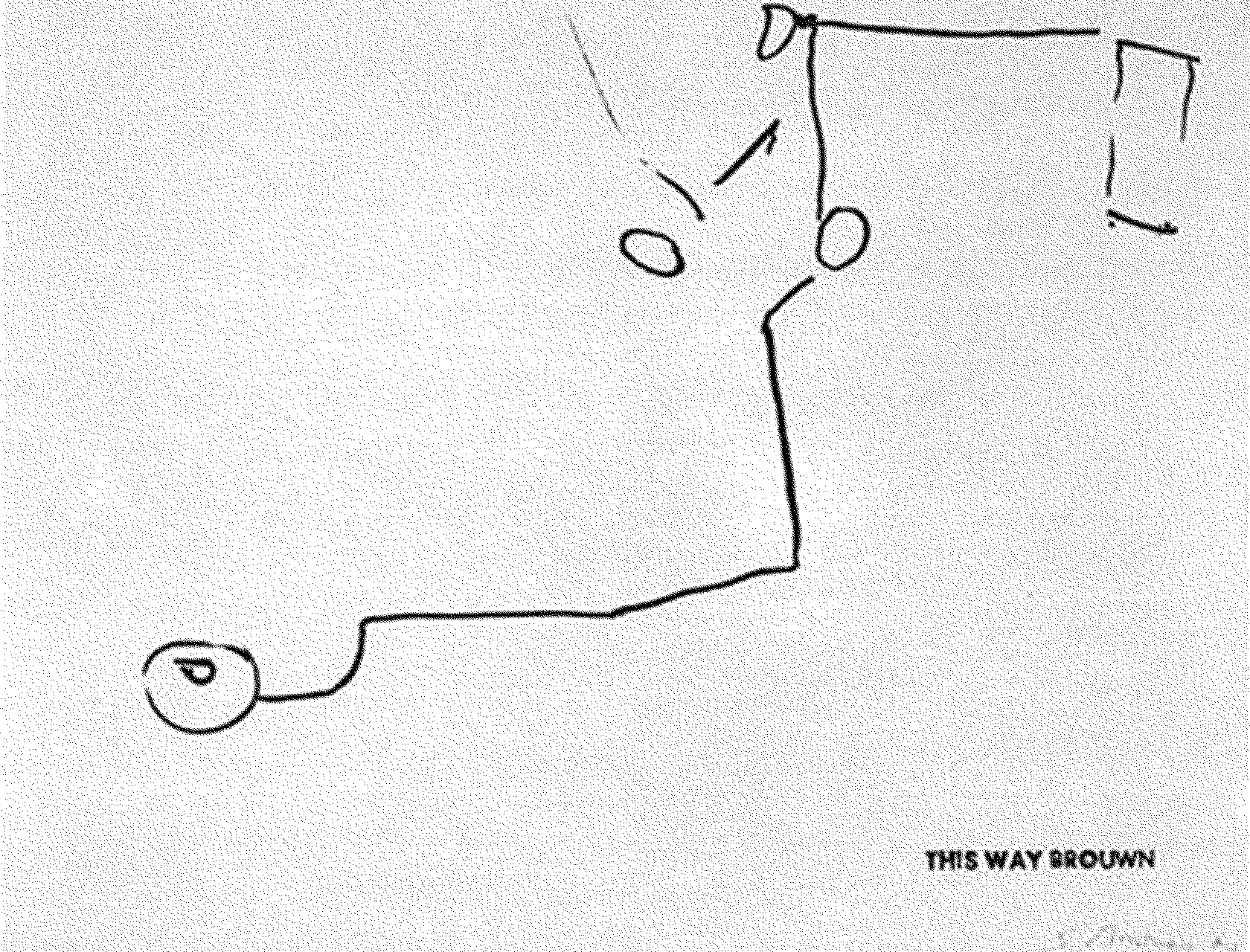

Such a random situation has been the object of interest of Stanley Brouwn. In This way Brouwn (1964), he stood in a non-specific place, ‘a’, and asked random passers-by on the street of Amsterdam to show him the way to a certain place ‘b’— like the Dam Platz 1. The time necessary to walk from his position ‘a’ to ‘b’ has been compressed in the explanation given by the person he asked. The experience of space for every person is different and so the instruction and resulting drawing varied each time. These maps lack any street names, show a tendency for simplification and straightened visualisation based on a memory. [Fig. 15 –17] When compared with each other these guides provide an example of how different each person’s way of looking is. “As they were drawing the people talked, and at times they talked more that they drew. On the sketches we can see what the people were explaining. But we cannot see what they have omitted, because they had trouble realizing that what might be clear to them still requires explanation.” 2

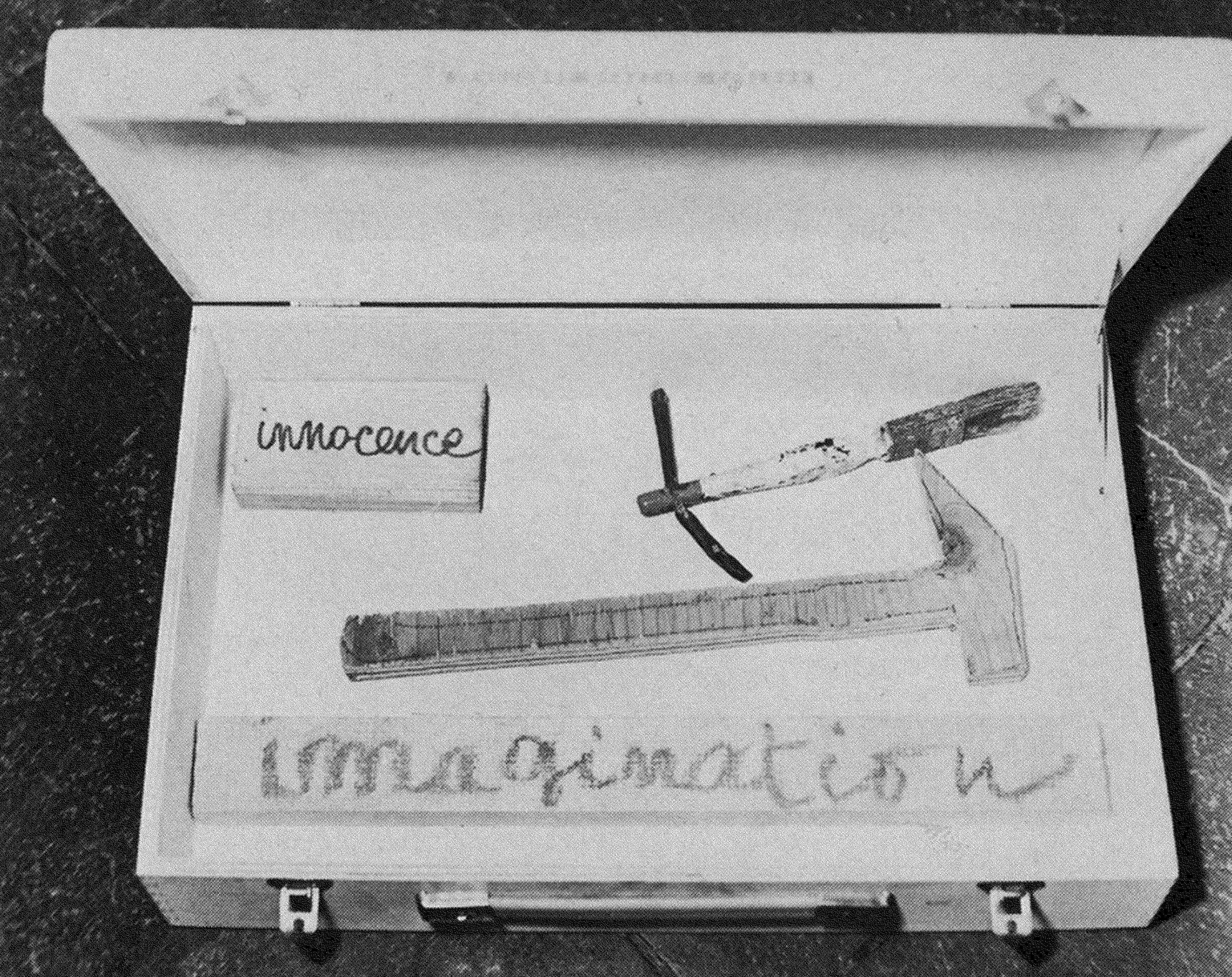

5. TOOLS FOR IMAGINATION 1

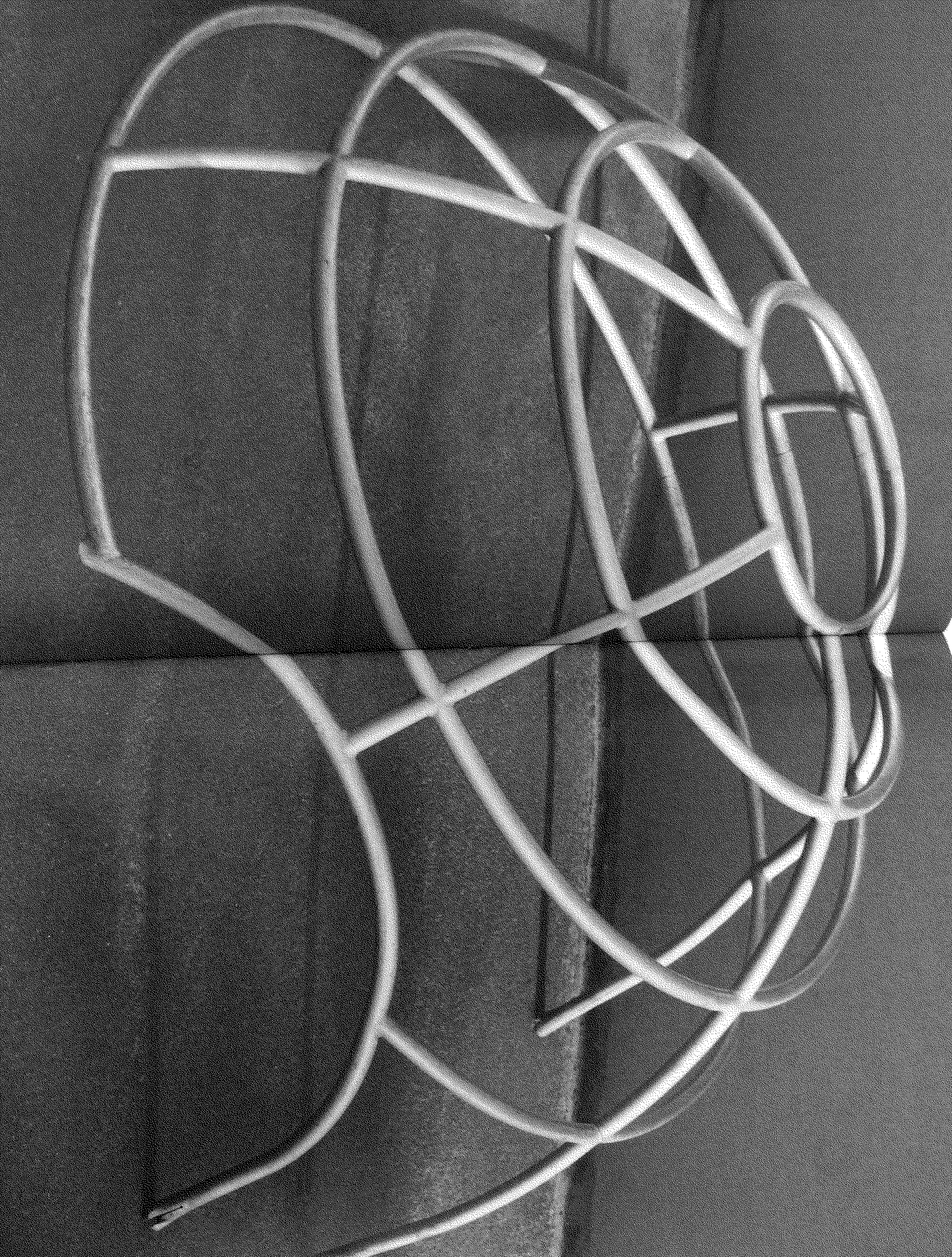

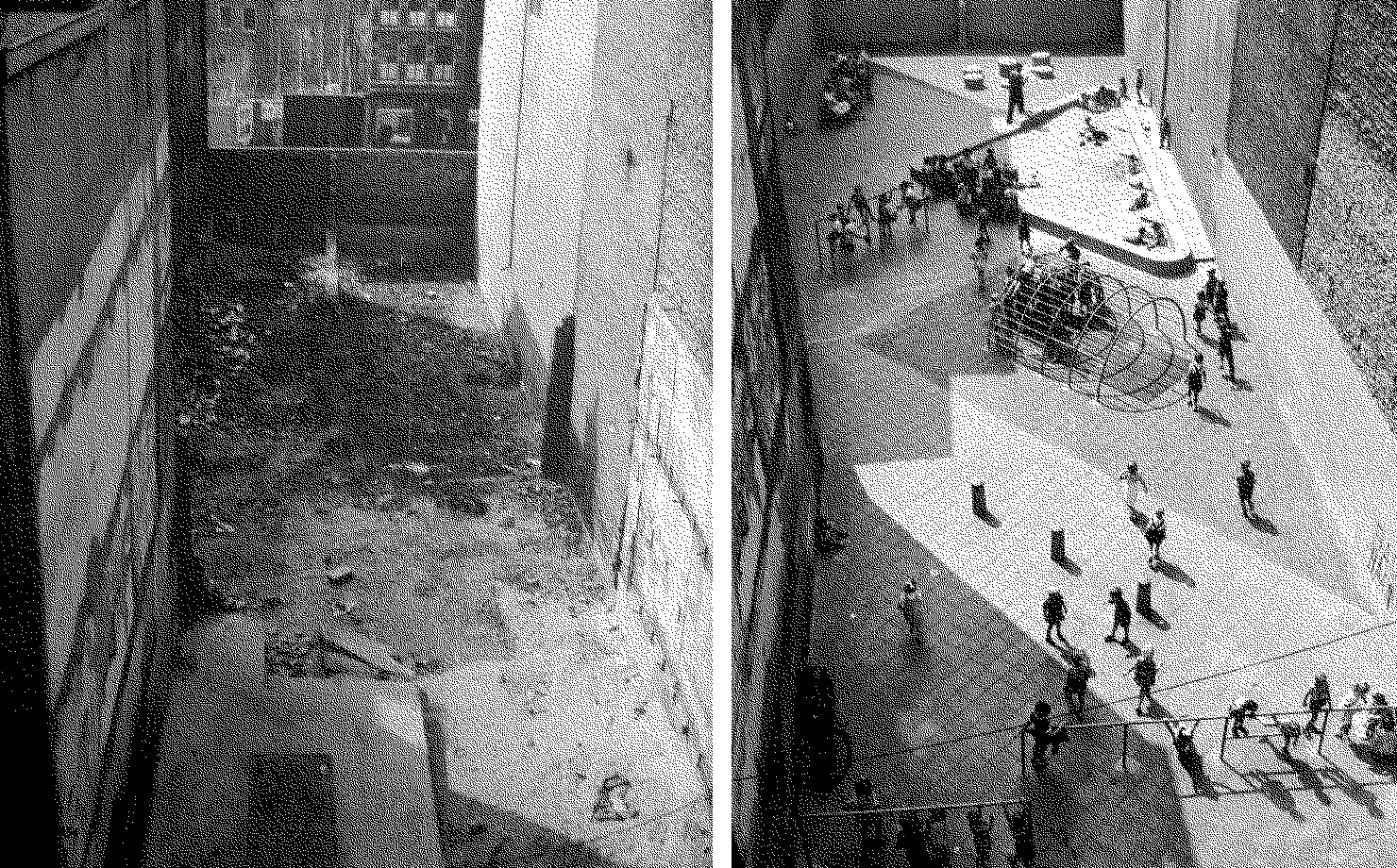

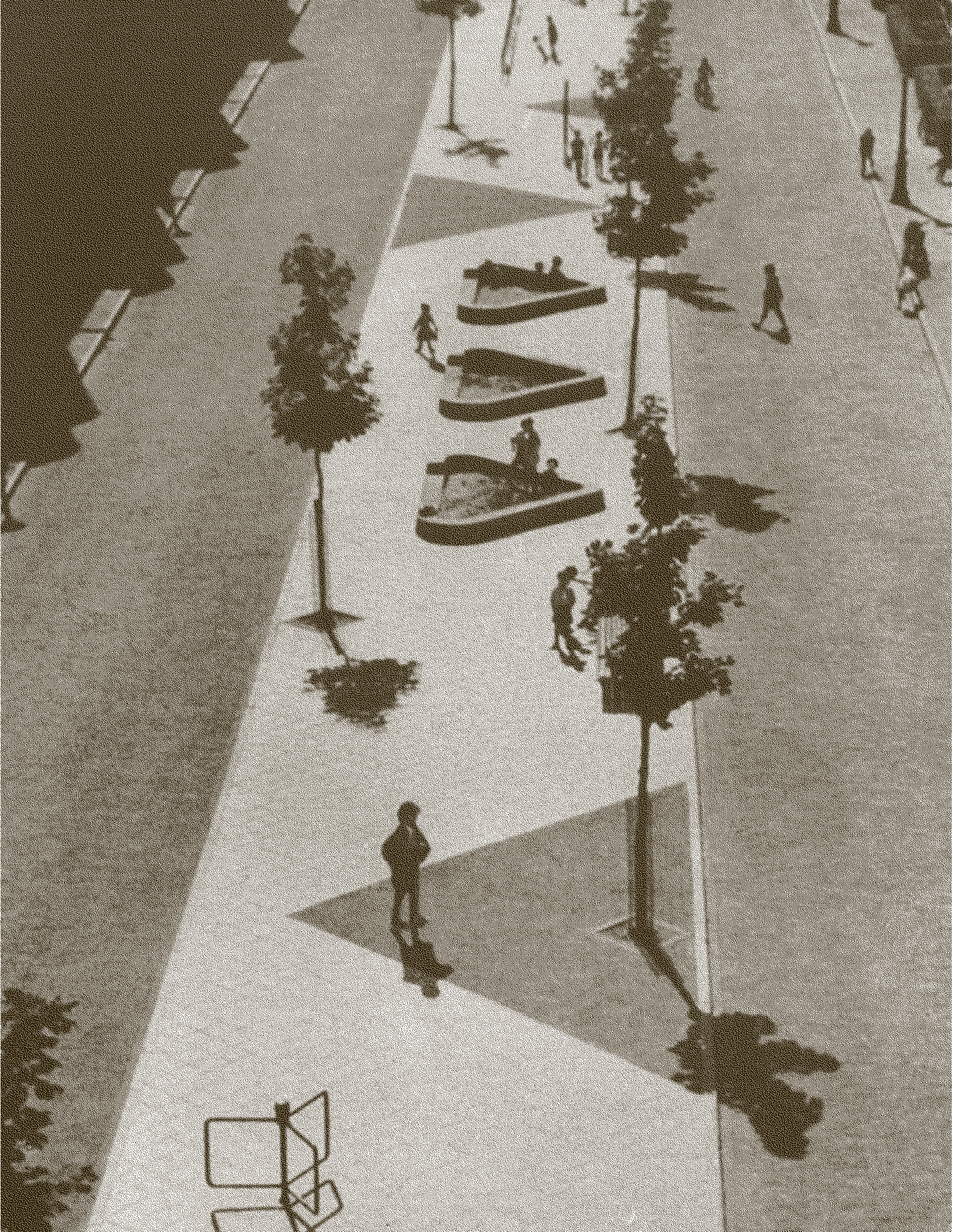

Passing through the streets of Amsterdam, one can encounter a paved square where several sculpture-like geometrical metal objects have been placed. [Fig. 18] It is very likely, that it is one of the remaining playgrounds designed by Aldo van Eyck. [Fig. 19]

His playground design career begun when he started working for the Urban Development Department in Amsterdam in 1946, at the age of 28. However fascinating the construction sites and the streets of the post-war city were, they were also unsafe, especially with the increasing amount of cars on the streets. It was clear at that time that public play spaces were a growing necessity. A part of the social education plan was to encourage children to develop abstract thinking and become open-minded adults interested in culture.

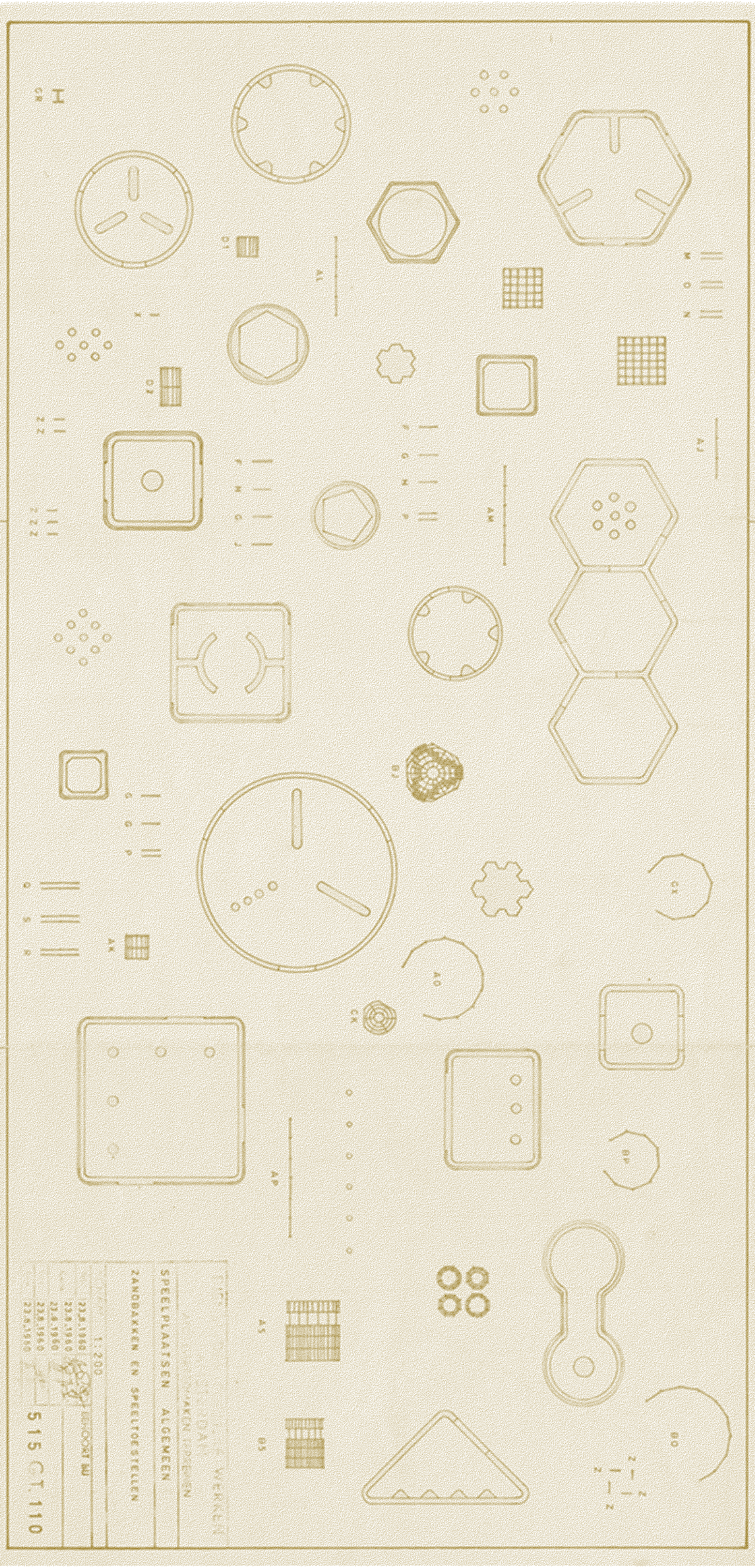

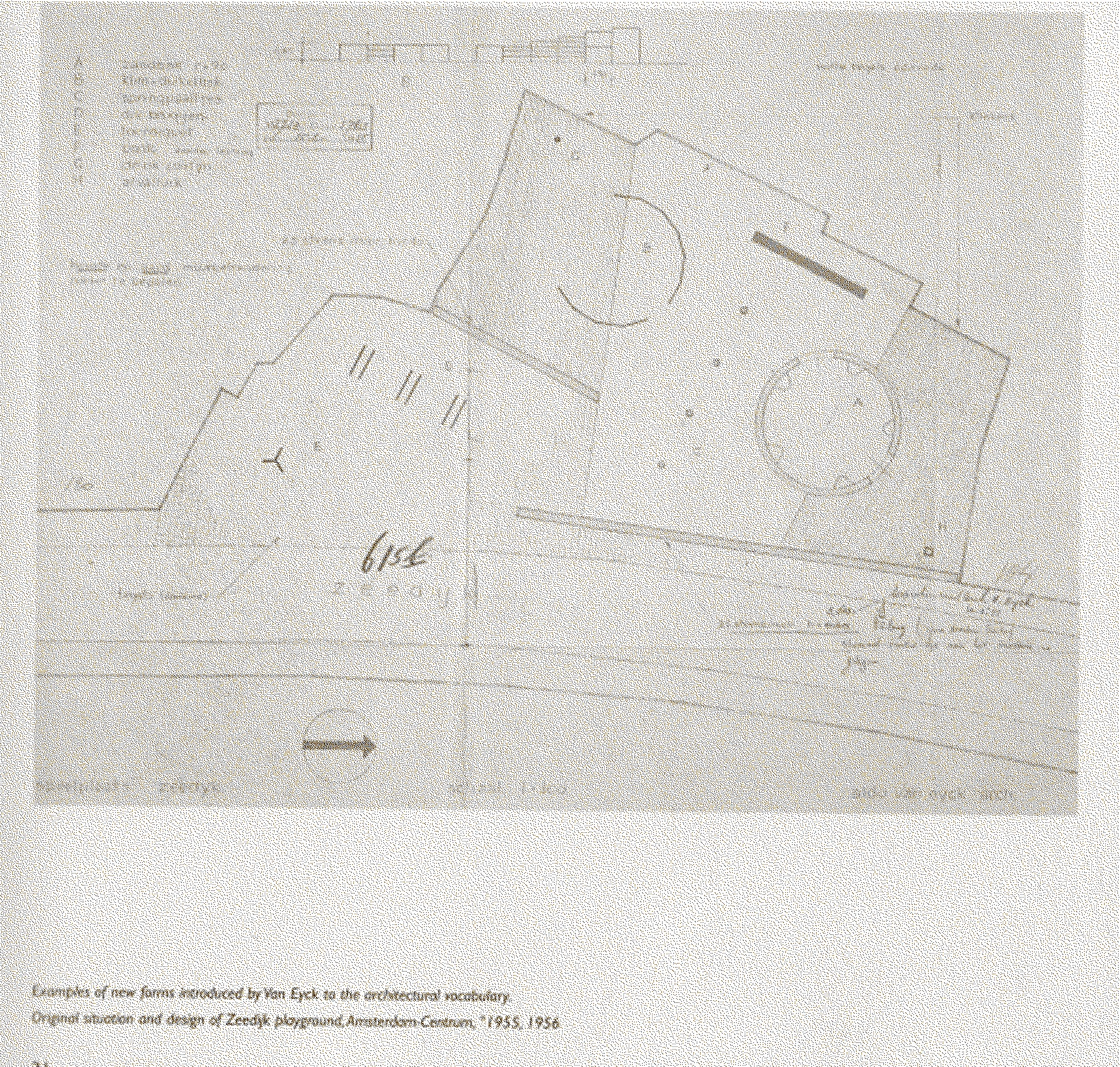

Empty lots between buildings, spaces used as garbage dumps hidden behind dilapidated walls, were gradually adopted for public playgrounds. [Fig. 20] Thus, the architect often had to adjust his designs to the existing urban space. The elements of each playground were composed in a non-hierarchical system in which all elements were equally important. All the components could be used according to the spacial properties of each space. [Fig. 21] Although consisting of a repetitive pieces, in each location the layout was different. Van Eyck was eventually responsible of the appearance of around 700 playgrounds dispersed around Amsterdam (constructed between 1947-78).2

The playground elements that he designed were almost always immobile, so the way of moving around them always had to be imagined. [Fig. 22–23] “Van Eyck encouraged children to discover shapes, forms, proportions, and distances, and develop their imaginations on their own terms. The form was only a suggestion of what it could be. Wherever you were in the playground, you were never on the edge, but always surrounded by something. (...) going from one place to the other. There was a whole sequence of games you played with other kids on the way.” 3

Van Eyck’s multi-centered focus was present not only in

his design, but also in his manner of thinking. He would say

“‘Do you see that, and that, and that?’ And then he immediately questioned his view, turned the other way around and said

‘But there is also that, that, and that!’ ” 4

The balance between the filled-in space and the space left empty was a space open for any games. No artificial borders were present as people (for example parents) would form a barrier, sitting on benches placed between the road and the playground. If that was not the case, bushes or naturally present obstacles such as walls formed the boundaries. Hence, the space remained both open and safe. As it is natural to decide to jump from one stone to another when crossing a river, in like manner no rules were necessary on a playground. The only rule of the playground might have been that you had to participate as soon as you found yourself in it.

Falling is an integral part of balance. Just as we learn how to fall, we learn how to fail. The simple play of maintaining balance on the somersaulting frame can be a long-term profiting lesson, because it is easier to fall when we play.