♦ ♣ ♥ ♠

Creativityas Discovery

●

ABSTRACT

In the field of graphic design, creativity in research and practice is actively encouraged. But what does it mean to be creative? How does it present itself? My thesis aims to investigate the role of creativity within the creative process and research the role it plays in relation to the unexpected outcome. I always had fascination for the unexpected surprises appearing in the creative process. In fact, in any artistic environment, chance, or the spontaneous random event has played a vital role in the creative process. Is today till the case? Can unexpected outcome be a key strategy within the field of graphic design? The most essential part of the creative process consists of exploring an acknowledged map that is still party undiscovered. Because we often don’t know where we are heading, serendipity is important for finding our destination. In fact, the less detailed the map, the more important Darwinian trial and error becomes. Personally I find the creative process more interesting than the final outcome. It is for me the place where every idea gets born and where every possibility can be explored. Indeed, the entire creative process can be compared to exploring a map that is still partly undiscovered. But more importantly, I will consider how exploration does not just present new, surprising routes… But instead present unexpected outcome as an entirely new conceptual map.

○

INTRODUCTION

One of the greatest preoccupations not only of our culture but of our civilization is the question: What is creativity? Dating back to the dawn of recorded thought, it wasn’t until the advent of modern psychology in the early twentieth century, that our answers to the question begin. Although, I have the feeling that creativity is somewhat an obscure concept. Somehow difficult to define in one sentence… What does it mean to be creative? What are the criteria to call an artwork creative? The answers to this questions are not that simple. The reason why creativity is perceived as a concept that is hard to grasp is that scientists haven’t really figured out what happens in our brain when we invoke a creative idea. In fact, we can hardly invoke a creative idea on demand. But more interestingly, it shows up quite randomly. If we look from another perspective, we could ask ourselves: What is the probability to encounter creativity in the creative process? And if we talk about probability, can we then talk about chance? My thesis aims to investigate the role of creativity in relationship to the unexpected. Chance, the spontaneous, the happy accident. Random events have played a vital role in the creative process. How can the creative process be design in order to construct an unexpected outcome?

The creative process can be defined as the development of any kind of idea or anything valuable of form. This process can refer to the making, assembling, arranging, associating, patterning,… and moreover the initiation of actions and proceedings towards a result. Generally, the creative process is the place where every idea are born, where every possibility could be explored. It’s the place where discoveries should be made. Discoveries could be for example the result of using intuition and imagination during the creative process, like this two elements, they play a dominant aspect in linking up ideas whose connection are never suspected. Creativity is not creating something that did not exist before, creativity is to discover what has always been there but had remained hidden from view.

I believe that the role of chance in design, can be pursued as a method for creative practice in order to discover new possibilities for creation. In the field of graphic design, creativity in research and practice is actively encouraged. Creativity in itself is a process that consists of internalizing the rules that define a domain [preparation], of letting the acquired knowledge digest [incubation], while we wait for an insight to appear [illumination], and of assessing and executing the insight [verification].

The following thesis is based on the structure find in ‘The Art of Thought’ by Graham Wallas (1858-1932), English social psychologist and London School of Economics co-founder, which in 1926 wrote an insightful theory outlining the four stages of the creative process. I was inspired by Graham’s theory to contextualize my thesis. This thesis will explore the three first phases preparation, incubation and illumination.

Furthermore my thesis aims to research and reflect upon the role of creativity within methodologies and tools. How does unexpected outcome get influence by methods? by tools? I will try to analyze the work of different practitioner and try to provide a new context for chance procedures in graphic design. But before proceeding to a discussion of methods and tools related to creativity, we should keep in mind Pasteur’s famous dictum, “chance favors the prepared mind”, because this will turn out to say more about what can be said about creativity. Pasteur was speaking, of course, about a very specific kind of creativity, namely, experimental scientific creativity. The quote actually begins: “In the fields of experimentation,” and was in part concerned with the question of whether experimental discoveries — also called ‘serendipitous’ — are really just lucky accidents? Pasteur’s theory seems for me to be relevant to all forms of creativity. However, one can interpret Pasteur’s dictum as follows: There is a (perhaps very large) element of chance in creativity, but it is most likely to occur if the mind is somehow prepared for it. Context shows that by ‘preparation’ Pasteur did not mean being born with the ‘creative’ trait. He meant that existing knowledge and skills relevant to the creative leap first had to be sufficiently mastered. For what can all that ‘preparation’ do but train our expectations, establish conventions, move in familiar, unsurprising directions?

In defining creativity as the production of something that is not only new and valuable, but also unexpected, it seems to have put an insuperable handicap on taking the path of preparation. For whatever direction the preparation actually leads, it cannot be unexpected. This seems paradoxical, but again, a closer look at Pasteur’s dictum resolves the apparent contradiction. The suggestion is not that preparation guarantees creativity. Nothing guarantees creativity. What Pasteur means is that the only way to maximize the probability of creativity is preparation. He correctly recognized that the essential element is still chance — like the unexpected — but this fortuitous factor is most likely under prepared conditions.

♦

CHAPTER I

Chapter I. PREPARATION

First things first. Preparation is a procedure for a future event. Preparing means to get ready. But, like preparing for holidays, each person as their own way to prepare. For example, some people will prepare months in advance, some will prepare with the famous ‘to do’ list, or ‘not to forget’ list, some will research in advance what the weather will be, or how to go from point A to point B. We can compare the preparation phase to planning things ahead. Also in the field of design, the preparation phase analyses a certain problem at first and then investigate the problem in many directions.The preparation phase is actually collecting intellectual resources and researches in order to construct new ideas. It is a fully conscious stage and involves research method and design method. As well it is an exploration phase where the maximum should be explored. Wallas writes: “The educated man has, again, learnt, and can, in the Preparation stage, voluntarily or habitually follow out, rules as to the order in which he shall direct his attention to successive elements.”|01||01| Albert Rothenberg, Carl R. Hausman, 1976. The Creativity Question.

I. I. Research method

There are too many ways to classify research, and types of research. But, in the broadest sense of the word, the definition of research includes any “gathering of data, information and facts for the advancement of knowledge.”|02||02| Shuttleworth, Martyn 2008. Definition of Research. Explorable.com.Reviewed 15 November 2015. Another definition which might emphasizes the importance of research: “A studious inquiry or examination; especially investigation or experimentation aimed at the discovery and interpretation of facts”.|03||03| Creswell, J. W. 2008. Educational Research:Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Indeed, the goal of the research process is to produce new knowledge or deepen understanding of a topic or issue.

Furthermore, I believe that in research methodologies, designers, artists or craftspersons will seek intuition besides objective knowledge. I will say that research methodology in design is something which varies from one person to another. One might be subjective while the other objective. One might investigate every possibility (e.g gathering data and linked databases, investigate contextual research, technical research, …) while the other might focus on one thing only. Research has to do with who you are as a designer; thought great design is built on good research.

Let’s take the example of a typeface. History made by Peter Bil’ak. In the article, The history of history, Peter Bil’ak reflects on the process of creating this skeletal system where different styles are imposed on a Roman capital base. His research method illustrates experiments, as well as inspiration sources such as polyhistorical model of ‘Milan Kundera’s Immortality’ which provided him the theoretical foundation of the project. This way the typeface mixes personalities of the past and present, describing an imaginary dialogue between the German poet Goethe (1749-1832) and the American novelist Hemingway (1899-1961). First of all, Bil’ak’s research process led him to construct History accordingly.

But what I like about the project so much is how the type system was developed. As a matter of fact Bil’ak started experimenting in the early 90’s with decorative layering, he explains in an article ‘The Making of Typographic Man’ by Ellen Lupton. So you might ask, How History came along? Only years later (2002), when Bil’ak was asked to work on a proposal for the Twin Cities typefaces, he proposed the idea of a typeface system inspired by the evolution of typography, actually the one he was working years before but never finished due to the technological limitations.

The more I think about this anecdote and more I think that Peter Bil’ak was quiet lucky to find another purpose for the research he had started but never visualized. I realize that research is an actual intellectual resource which active or not is anchored in our memory. Finally, the research you might have made years ago might pop up from the back of your head at the most unexpected moment.

History by Peter Bilak - Typotheque ©

I. II. Design method

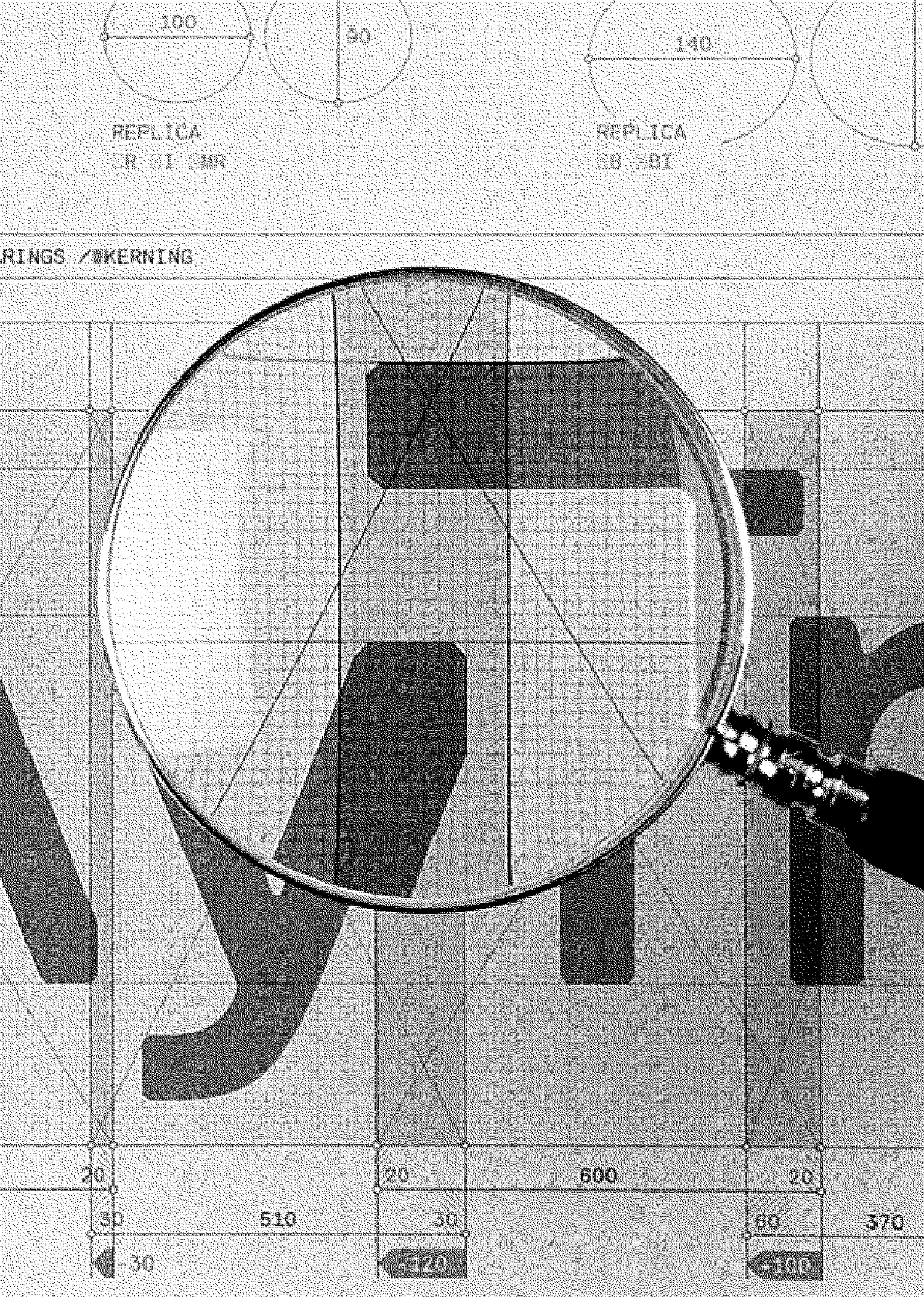

Design methods have influenced design practice and design education. A good example would be Swiss Design, or also called ‘International Typographic Style’, which emerged in the post-World War II. Everyone knows this particular style for its simplicity and its aesthetic beauty that arose out of the purpose of the thing being designed. Aesthetic beauty wasn’t itself the purpose. Ernst Keller (1891-1968) professor at the Zurich School of the Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) did not teach a specific style to his students. He rather taught a philosophy of style that dictated “the solution to the design problem should emerge from its content.”|04||04| Shuttleworth, Martyn 2008. Definition of Research. Explorable.com. Reviewed 15 November 2015. Designers were seen as communicators, not artists. In fact, this design method began with a mathematical grid because a grid is the most legible and harmonious means for structuring information. The text was then applied, most often aligned flush left, ragged right. Fonts chosen for the text were sans serif, a type style believed to “express the spirit of a more progressive age”|05||05| Shuttleworth, Martyn 2008. Definition of Research. Explorable.com. Reviewed 15 November 2015. by early designers in the movement.

By following this design method, the progressive, radical movement in graphic design saw creativity emerging from the constraints of the method itself. Which allowed each designer to pay extra attention to the creative process, for example: attention to detail, precision, craft skills, standard of printing as well as a clear refined and inventive lettering and typography. Their design method turned out to be a foundation for a new design movement. In 2008, the Swiss duo Norm — Dimitri Bruni and Manuel Krebs — produced a typeface called Replica by reducing the underlying grid from 700 units to 70. The result was unexpected. Bruni explains the process “The focus is on the exploration of the boundaries of the possibilities of drawing, or the precision of drawing offered by FontLab software. We have reduced these possibilities by factor 10, a concept that was defined before the actual drawing process had started and which had a very strong impact on the resulting drawings. In the sense, both projects are about causal systems that are defined by rational or mathematical principles and have a strong impact on their results. A sort of numerical design process, as it were. But despite these formal definitions, Replica offered far more room and need for intuitive decisions than I would have expected”.|06||06| Dimitri Bruni on Replica. Graphic Design: Now in Production. Their design method intrigues me, by using the already existing grid the duo Norm actually set on top of that new constraints (reducing the possibility by factor 10) which were set before hand. This method actually ables Replica to be unique as the unexpected outcome comes from the limitation itself.

Norm, Lineto, Replica Type specimen - Lineto ©

Replica Typespecimen - Sang Mun ©

Design methods took advantage of the design community by helping to create introductions that would never have happened if traditional professions remained stable. Design has been by nature an interloper activity, with individuals that have crossed disciplines to explore and discover. I would like to mention a quote from John Chris Jones (1927). Which to my eyes reflects the work of the typeface History, in which Peter Bil’ak focused on the creative process rather than its market potential.

I. II. I. Where process meets method

When process and method are discussed, they tend to be used interchangeably. However, while they are two sides of the same coin, they are different. Process (lat. processes–movement) is a naturally occurring or designed sequence of operations or events over time which produce desired outcomes. Process contains a series of actions, events, mechanisms, or steps, which contain methods. Method is a way of doing something, especially a systematic way through an orderly arrangement of specific techniques. Each method has a process. Design methods are concerned with the ‘how’ and defining ‘when’ things happen, and in what desired order. Design implements so many tools and techniques where there are many variables that affect the outcome. Because logic and intuition interplay with one another. Two people can, therefore, use the same method and arrive at different outcomes. How could the method we use (as graphic designers) influence unexpected outcomes?

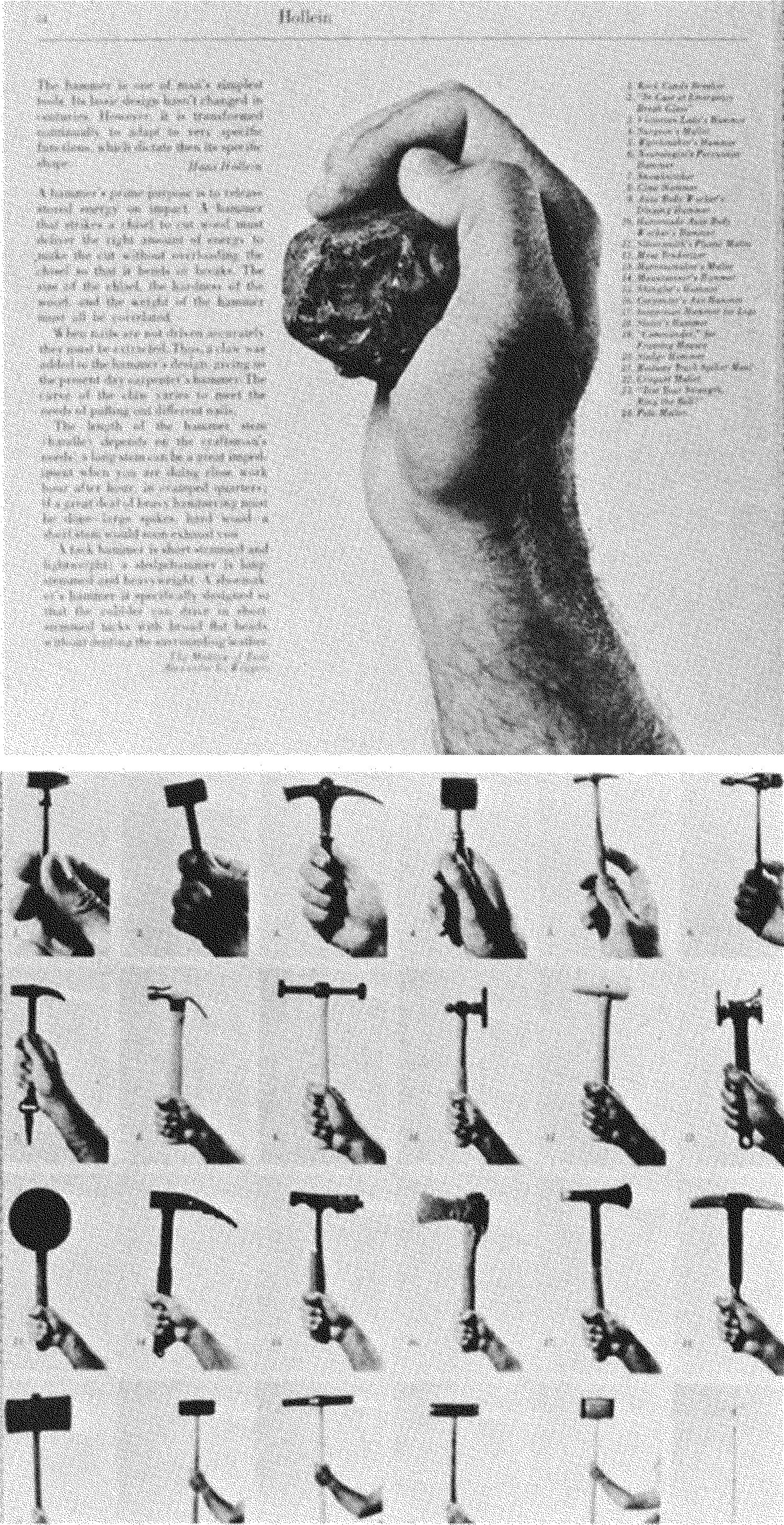

And how does the tools we use influence unexpected outcome(s)? I would like to illustrate the work of Hans Hollein (1934 -2014), Man TransForms. In the book ‘Graphic Design: Now in Production’, Jonathan Puckey explains:

Indeed, tools define the way we work, they shape our work, they are the essential element to creation. Tools are crucial elements among the creative process and method we work with. Without tools we wouldn’t be able to create.

MAN transFORMS by Hans Hollein ©

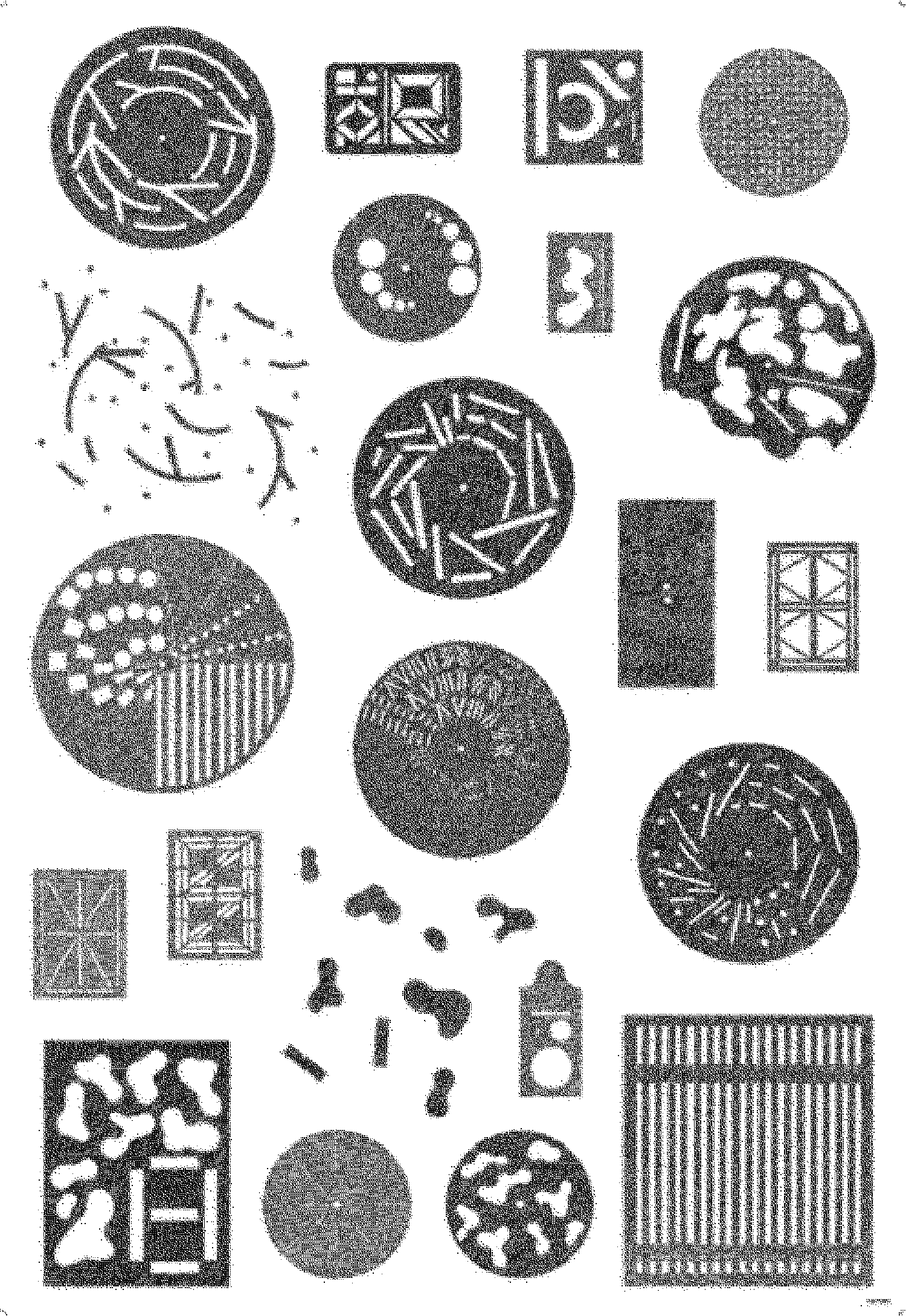

I would like to relate to the work of Karl Nawrot which uses a technique to create evolving shapes, all his work goes through the same process of assisted-drawing. Nawrot creates his own tools which can be anything from ink stamps to circular record templates and geometrical stencils.

Templates For Records, carton, plastique/cardboard, Karl Nawrot ©

Creativity lies within the tools he builds, these tools and devices permits him to investigate and explore deeper into the possibilities of shapes and patterns and to create new sorts of visuals. The creativity of this established drawing relates also to the relationship the tool and drawing have. What is fascinating about these tools? Why is the outcome so special? What I like about these tools are the possibilities they offer when you look at them. Each tool can create diverse shapes and by combining new shapes together, it creates new forms. I always thought that these assisted-drawings were the outcome of an unexpected process, but apparently not, or at least not totally. Karl Nawrot explains in an interview in Collection revue:

Still, these drawings are somehow the result of an expected outcome as the drawings will always be different. Furthermore I will add another little anecdote on the development of Karl Nawrot’s tools. The idea of the tool came after three months in New York where Karl Nawrot had done nothing but walk. One day, he found a Ronald McDonald stencil in the street and thought that it might be fun to use it to draw letter. Like the anecdote of Peter Bil’ak, in a certain way chance played a role in the creative process of his work.

I. III. Exploring new design method

Donald Alan Schön (1930-1966) was a philosopher who developed the concept of reflective practice and contributed significantly to the theory of organizational learning. Schön saw traditional professions with stable knowledge bases, such as law and medicine, becoming unstable due to outdated notions of ‘technical-rationality’ as the grounding of professional knowledge. Practitioners were able to describe how they ‘think on their feet’, and how they make use of a standard set of frameworks and techniques. Schön foresaw the increasing instability of traditional knowledge and how to achieve it. This is in line with the original founders of design methods who wanted to break with an unimaginative and static technical society and unify exploration, collaboration and intuition. Which brings me to Conditional Design Workbook which self combines elements to new design method.

Conditional design is often mention as a known example for their creative process. But what is creative in Moniker’s work? How is it different than other creative work? Conditional Design uses their process as their product and the most important aspects of their process is time, relationship and the development of its outcome. In fact, their creativity can be found between these three aspects : Time which restricts the development of its outcome — this one can be compared to the set of rules seen in the Swiss Style movement. Relationship, which Conditional Design is engaged to, this relationship can be seen as their tool. Additionally, they use this tool to design the conditions through which the process can take place. As well than, the development produces formations rather than forms. Conditional Design always presents their work as a documentation of the journey, of the making, rather than showing the outcome on its own. Finally, we could relate to the role of the unexpected in their design practice, in fact their design method will always seek for new rules and intuitive actions that present random logic visuals.

Conditional Design Workbook ©

I would like to conclude this chapter by underlining that graphic designers should use research and design as a combined method. From this uncommon method could generate other methods. For example, how would the typeface ‘History’ of Peter Bil’ak would have looked like if treated with the same methodology used by Conditional Design? This way unexpected outcome can emerge from the method and tools. I personally believe that new design method developed at a sufficient level can establish better process toward the field of graphic design. In fact, creativity shapes design methods by exploring new ways to execute them.

♣ CHAPTER II

CHAPTER II. INCUBATION

The second stage, is the incubation phase, a period of unconscious processing. There is much to be said in favor of laying a work aside to mature. In fact it gives the judgment time to operate, the mind is able to return to the work from time to time with a fresh outlook and check it from many different perspectives. I personally like to see the incubation phase as a big mood-board of ideas, which eventually will generate new ideas. It follows also that if new ideas are to be set aside to develop and newly finished works left to ‘mature’, there must be several things on hand at the same time in various stages of development. The continuity of attention is purposely shorted and interrupted partly on account of the rest this gives. Wallas wrote: “Voluntary abstention from conscious thought on any problem may, itself, take two forms: the period of abstention may be spent either in conscious mental work on other problems, or in a relaxation from all conscious mental work. The first kind of Incubation economizes time, and is therefore often the better.”|10||10| Albert Rothenberg, Carl R. Hausman, 1976.The Creativity Question. Like that, we can mention the importance of continuing going further with other things as sides projects for example, actually it might later help you solve the things you were struggling with.

II. I. The role of idea

In the text “The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism” T. S. Eliot (1888-1965), explores theories of how creativity works, by taking a curious look at how physical illness brings a near-mystical quality of poetry. In this text the key element of creativity are the presence of an incubation period when unconscious processing takes place. How big is the role of unconsciousness in the creative process? How does unconsciousness favor chance? How important is the incubation phase for producing an idea? In an interview, Stefan Sagmeister was asked to describe any method which was useful to him, to come-up with ideas. Stefan Sagmeister mentions a method used by James Webb Young (1886-1973):

Does Stefan Sagmeister use such methodology? Though I find a relation between James Webb Young’s method and Stefan Sagmeister’s method. Every seven years, designer Stefan Sagmeister closes his New York studio for a yearlong sabbatical to rejuvenate and refresh its creative outlook. In a TED talkshow, he explains the value of time off and shows the innovative projects inspired by his time in Bali. What can we learn from such methodology in relation to chance?

I believe that the best ideas come unexpectedly. But what if Sagmeister would never have gone to Bali? Would this life at that point be the same? What knowledge did he need in order to create this project? I think that in the case of Sagmeister, the environment played a major role in his discoveries, because in the end, it’s what surrounds you that inspires you.

The Happy Show, Stefan Sagmeister ©

The Happy Show, Stefan Sagmeister ©

In 1945, French mathematician Jacques Hadamard (1865-1963 ) set out to explore how mathematicians invent ideas in what would become ‘The Mathematician’s Mind: The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field.’ This one, introduces the process of discovery, using both his own experience and first-hand accounts by such celebrated scientists as Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) and Albert Einstein (1879-1955). But what Hadamard uncovered in the process, is how treatise were the general psychological pillars of all invention and the inner workings of the creative mind (whatever discipline it is applied to). Lewis Carroll (1832-1898) turns to a concept which has been expressed by many famous creator — the power of unconscious processing in productive work. French polymath Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) refers it to the vital workings of the subliminal self and T. S. Eliot argued it allowed for “idea incubation”. Lewis Carroll, too, speaks of its power:

Could the role of ideas find a place in new methodology where connection between other ideas are made? And what is the role of connection making in relation to chance?

II. II. Connection making

Lewis Carroll (1832-1898) affirms connection-making as the key to effective thought. Mentioning ‘connection-making’ in the context of creative process is crucial. For example in the case of ‘History’ by Peter Bil’ak . History was visualized only after years, and the reason why, is because Peter Bil’ak had connected his research with his project at that time. But another example would be the work of Blackout poem by Austin Kleon. In TED talkshow, ‘Steal Like An Artist’, Kleon explains how the idea of the blackout poem comes from. I noticed in the first sentence of his article

The word ‘every morning’ and ‘newspaper’ which both encapsulate time, reminds me that the outcome of this poem will always follow the same method, but will be generated differently, for example by the layout of the newspaper, the content of the newspaper, etc... Again such methodology brings the creative process forward, as seen in the previous chapter. Aspects such as time, relation and development are dominant in Kleon’s work. As well as using a similar method doesn’t mean a similar outcome. On the contrary, creativity reflects in the way Austin Kleon applies his method.

Blackout poem's Austin Kleon, by Stephanie Cheng ©

I will conclude this chapter by underlining the importance of connection making. In fact the essence of creativity lies in its discovery, like the making of unfamiliar connection of familiar ideas. Merging two or more ideas into something new. That is the reason why the role of the idea is indispensable in the creative process. The unconscious ideas and the connection making generated by our brain is better at filtering and processing data and intuitive decision-making. It is therefore the unconscious brain that generates the insights during the incubation phase, which are themselves a product of chance.

♥ CHAPTER III

CHAPTER III. ILLUMINATION

The illumination phase can be seen as the chance-opportunism phase like serendipity favoring scientific discovery. Introducing the word discovery, I would say discovery should be seen as an important form of creation that draws from our imagination. Discovery consists of making visible or known what has already been created by someone or something, but hasn’t been seen before. That’s why to discover literally means to uncover.

III. I. Creativity as discovery

Supporting Henri Poincaré's (1854-1912) insistence on invention as choice and George Lois’s (1931) conception of creativity as discovery. Rosamund Harding (1899-1982) writes: “The true novelist, poet, musician, or artist is really a discoverer. Ideas — the theme of a plot, a poem, a picture, a theme of music — come to him as a gift. The idea, ‘the seed-corn’ as Brahms called it, develops naturally. There may come a point where it branches in one or many directions; he is free at this point to follow one or other.”|14||14| Rosamund E. M. Harding,1942. An Anatomy of Inspiration In the interview ‘On Creativity’ George Lois (1931), legendary art director discusses the way he discovers ideas within the contemporary culture. He says:

The entire creative process can be compared to exploring a map that is partly undiscovered. Some important places and connecting roads are missing, and the process of exploration is essential for making the map complete. A classic example of an unexpected discovery would be how Columbus discovered America in 1492. If Christopher Columbus hadn’t tried to land on the East Indies going West (instead of East), his discovery might not have been made. What does the discovery of Columbus teach us as a method? The experience of Christopher Columbus can be analyzed as a certain method; by trying something new, something unfamiliar, discoveries can be uncovered. Such a method can be seen as applying chance in your favor.

A good maxim for any researcher is ‘look out for the unexpected’. I believe, we, as graphic designers are researchers too. Which means this maxim applies to the field of graphic design as well. I will name Jerome Bruner (1915) who considered which disposition is most fruitful to the art of discovery:

As a matter of fact each possibility that is tried out in the creative process, even a dead end, teaches us something that later will expand the knowledge structure. Bruner illustrates what is perhaps the most insightful lens on problem-solving ever crafted — the English philosopher Thomas Dewar Weldon’s (1896-1958) distinction between difficulties, puzzles, and problems. Bruner explains: “We solve a problem or make a discovery when we impose a puzzle form on a difficulty to convert it into a problem that can be solved in such a way that it gets us where we want to be. That is to say, we recast the difficulty into a form that we know how to work with — then we work it. Much of what we speak of as discovery consists of knowing how to impose a workable kind of form on various kinds of difficulties. A small but crucial part of discovery of the highest order is to invent and develop effective models or puzzle forms. It is in this area that they truly powerful mind shines.”|17||17| Jerome Bruner, 1962.The Act of DiscoveryAlong these lines Einstein (1879-1955) himself brought out:

III. I. I. Intuition

What is intuition? and How does it work? Intuition is a phenomenon of the mind, describing the ability to acquire knowledge without inference or the use of reason. I find difficult to define how intuition exactly works, it might vary from a person to another. Once the Hungarian photographer Brassaï (1899-1984) asked Picasso (1881-1973) whether his ideas come to him by chance or by intuition, Picasso add the following answer:

Pablo Picasso in his atelier

The decisive power making of the unconscious mind takes place in Picasso’s work. Furthermore intuition plays a role with time, in fact there is no time for extensive analysis or comparison of different moves. What is interesting about this so called ‘intuition’ is that it actually follows the knowledge that was established during the conscious stages of the creative process. All the technical and further knowledge which are gathered consciously are taken into account when our intuition is telling us that we are making the right decision. Could intuition be a tool to methodology? And how does intuition relate to chance? In Bergsonism, Gilles Deleuze emphasizes three distinct sorts of acts, which in turn determine the rules of the method: The first concerns the stating and creating problems; the second, the discovery of genuine differences in kind; the third, the apprehension of real time. Gille Deleuze writes:

III. I. II. Imagination

In the 1878 book, ‘Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits’, Nietzsche observed: “In reality, the imagination of the good artist or thinker produces continuously good, mediocre or bad things, but his judgment, trained and sharpened to a fine point, rejects, selects, connects… All great artists and thinkers are great workers, indefatigable not only in inventing, but also in rejecting, sifting, transforming, ordering.”|21||21| Friedrich Nietzsche, 1878. Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits.

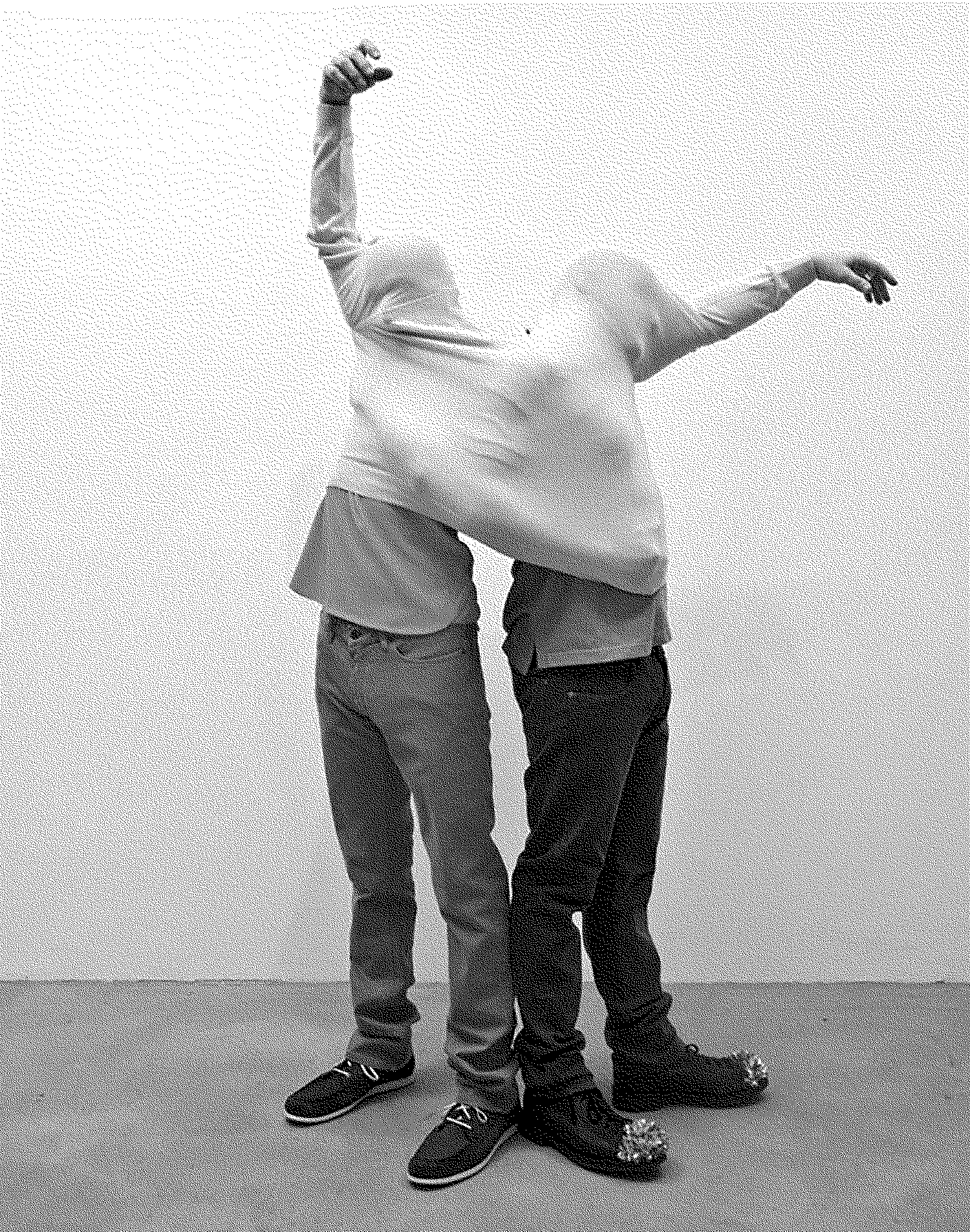

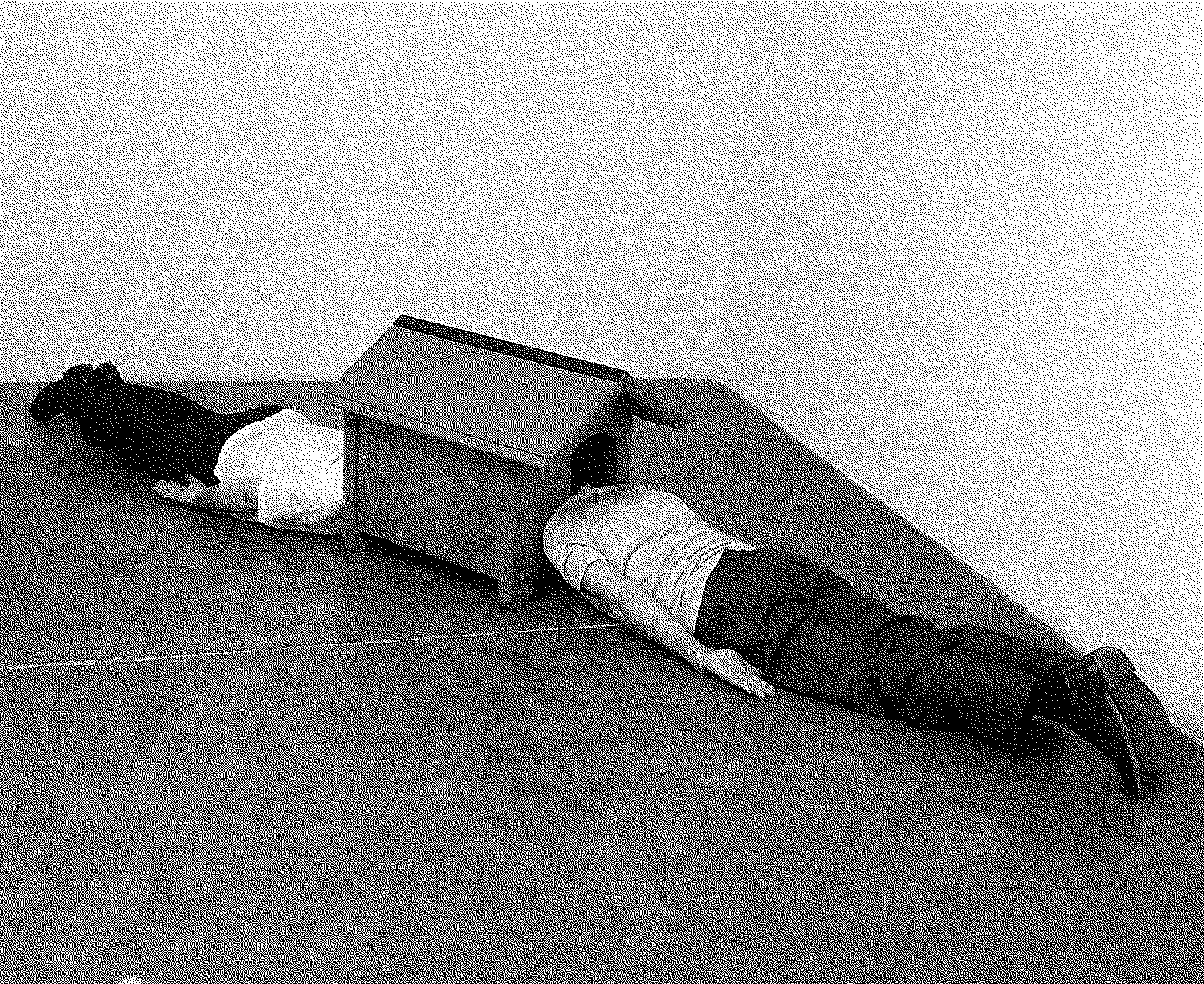

Creativity uses imagination to perceive that which we see and already know in new ways. I like to think that intuition and imagination consists in linking up ideas where connections was never suspected. For example, in the work of Erwin Wurm (1954), The One minute Sculpture — in which he poses himself or his models in unexpected relationships with everyday objects close at hand. He explains about his work: “I am interested in the everyday life. All the materials that surrounded me could be useful, as well as the objects, topics involved in contemporary society. My work speaks about the whole entity of a human being.”|22||22| Erwin Wurm, 2004, I love my time, I don’t like my time.

One minute sculpture, Erwin Wurm ©

One minute sculpture, Erwin Wurm ©

Wurm’s work is being inspired by what surrounds him and makes connections between physical, spiritual, psychological and political. Furthermore, Wurm uses intuition and imagination to create unexpected outcome which once again has a relation with time. Imagination like intuition are necessary elements to discovery, and Erwin Wurm uses creativity as a mental tool to find as many solutions as possible. The unexpected event takes place from the moment the viewer is engaged with the sculpture. How would the viewer react? would it necessary engage with the challenge of Wurm’s proposes? That is the mystery of the show, which for me becomes as interesting as the show itself.

III. II. Unexpected discoveries

III. II. I. Experimentation

At the Academy, students have at least once experimented. We often hear during a presentation ‘I was just experimenting’ to explain a design choice. I can’t remember when I started experimenting! Was it before the Academy? Or maybe it started with this class where the only advice from the teacher was ‘go and experiment’. Loved it. I wouldn’t know how or where to start, but I would just do something, see what happens; do something else, see what happens… and the process goes on and on. The process — and that might be explaining the reason why I have such an attraction for experimentation in general. The fact is, when you experiment, you have little expectation — also my fascination might come from the surprises and discoveries. Experimenting means being curious, believing you can make something that doesn’t already exist. If I mix element 72 to element 150, can it be outstanding? can it be insignificant?

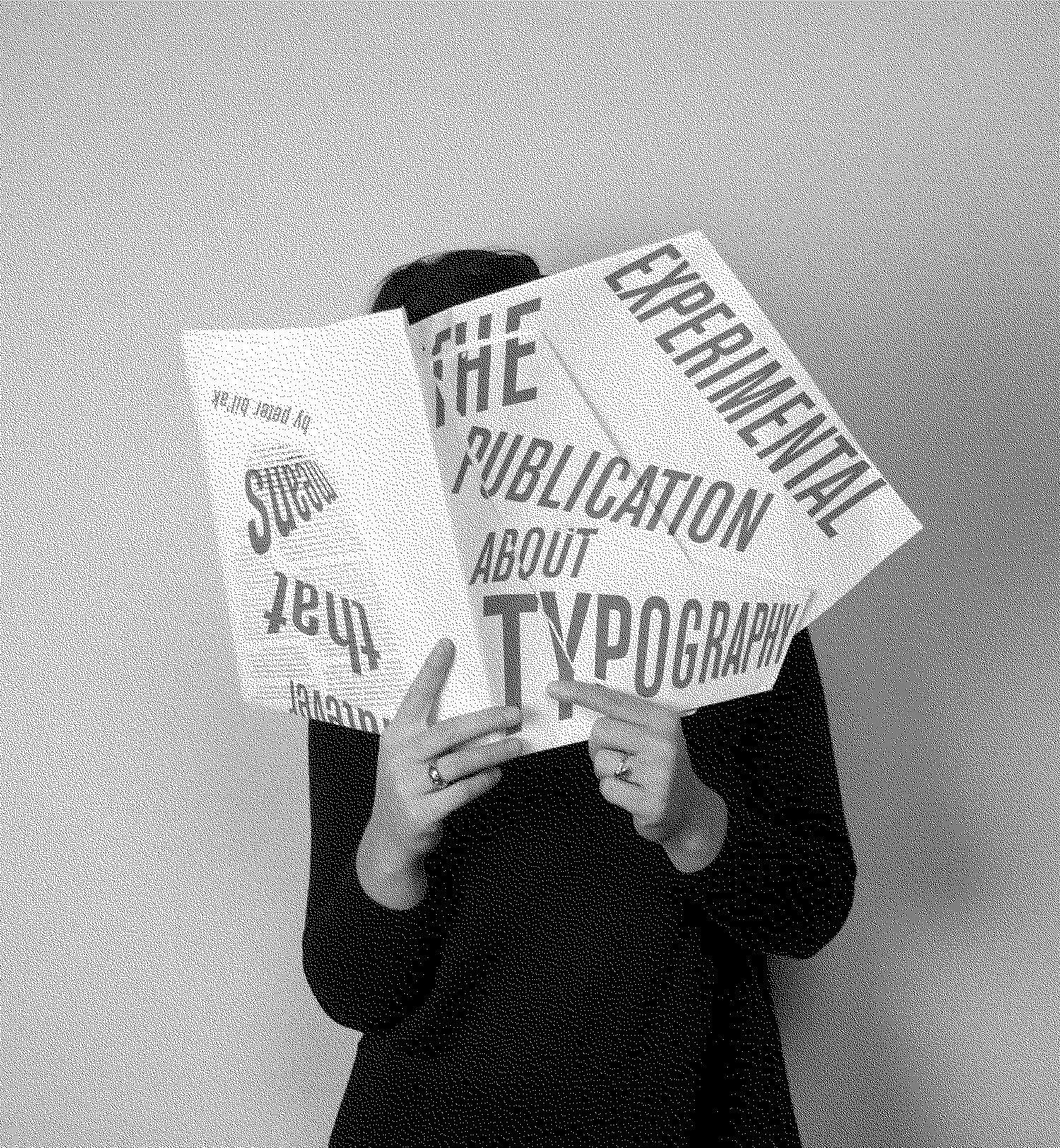

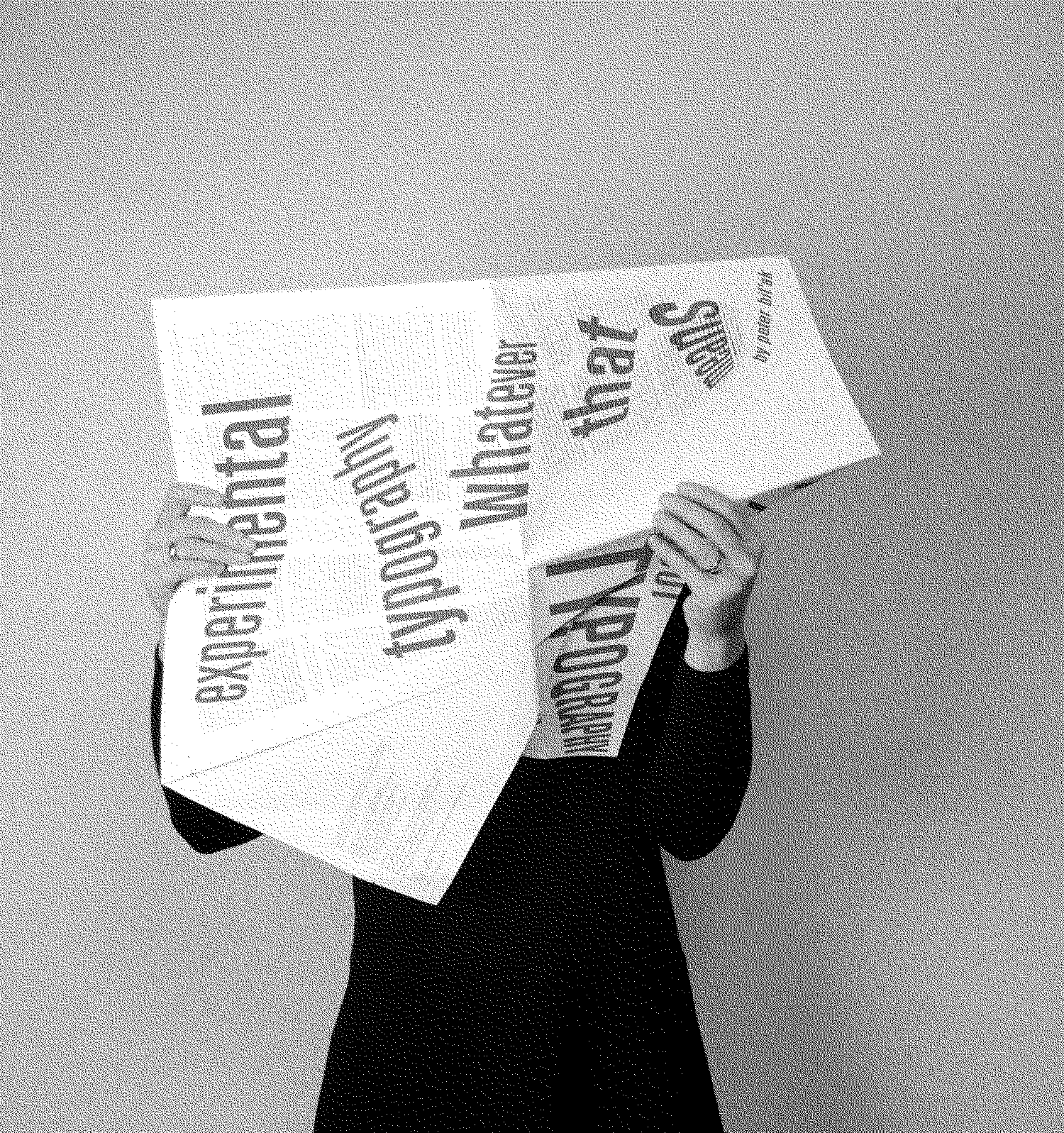

‘The experimental publication about Typography’, which I created during my time at the Academy, was experimenting with the layout — each article is defined by the folding of the publication.The size — unlike an A size the publication was randomly folded in the process phase. The typography adapts itself to the folded layout. The publication itself became something to experience in order to read it. I am now reflecting on this project and wonder if the factor chance appears in this publication? Of course, it is an unexpected way to open a publication, as when you turn the page, it goes from top to bottom from right to left… but the starting point of this project appeared when I was sitting in the train in France, and now that I think about it, I might have been in an incubation phase… This moment that you see something and later reflect it into your work. I remember seeing this man with his gigantic newspaper, he had trouble turning his page, the circumstance not helping. I thought it would be funny to have a publication where the experience of turning a page becomes almost a challenge. This project would have never existed, if I didn’t see this man and his newspaper on this particular day.

The experimental publication about Typography, Octavia van Horik

The experimental publication about Typography, Octavia van Horik

Many people have their own idea or definition of what an experimentation is, still, the word ‘experiment’ appears often in different context. Experimentation in art needs to be approached very differently than in psychology or in a scientific context. Through, the word itself experiment, expert and experience, derive from Latin experiri, ‘try’. In the following definition of ‘experiment in art’, I mention innovation which means to innovate; literally ‘to introduce something new’. It also means to make changes in anything established. Which is the historical meaning of the word’s root: to renew, to alter. Innovation does not necessarily mean something new. It means doing something unfamiliar, often with old familiar things.

Experimentation in art is an attempt at something new or different. True experimentation means taking risks. Not knowing the outcome but trying something that you think will be successful, although you have no proof. It is about innovation, but it is not always about formulaic nor is there an established set of rules. Let’s take the example of Picasso, which explains “To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing…” by saying this Picasso doesn’t know what the outcome will be, Picasso has in fact an experimental approach towards his work, by trying new things and in this manner taking risks within the decisions that he made during the creative process. While experiments in psychology is the work done by those who apply experimental methods to the study of behavior and the processes that underlie it. Experimental psychologists employ human participants and animal subjects to study many topics, including, among others: memory, cognition, learning, motivation, emotion… Finally, experiments in science is a test under controlled conditions that is made to demonstrate a known truth, examine the validity of a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy of something previously untried.

Looking at these three categorization of experimentation, each one of them has their own definition. Though experimentation is a legitimate research method. In the field of graphic design, experiments have been used to signify anything new, unconventional, defying easy categorization, or confounding expectations. Many designers have succeeded in this path, still I find it difficult to point a finger on ‘what is an interesting experiment and what is not’. Personally when I experiment, I always try a bunch of stuff because I never know what its going to be. Yes, there will be failings along the way. Besides, I consider mistakes as part of the glorious process of creating. They are not to be feared, but rather embraced as opportunities. Actually, it is when experiments go wrong that we find things out. Like Alice’s unexpected slide down to the rabbit hole. The unknown can be a marvelous misstep into a channel that carries the artist toward exquisite possibilities.

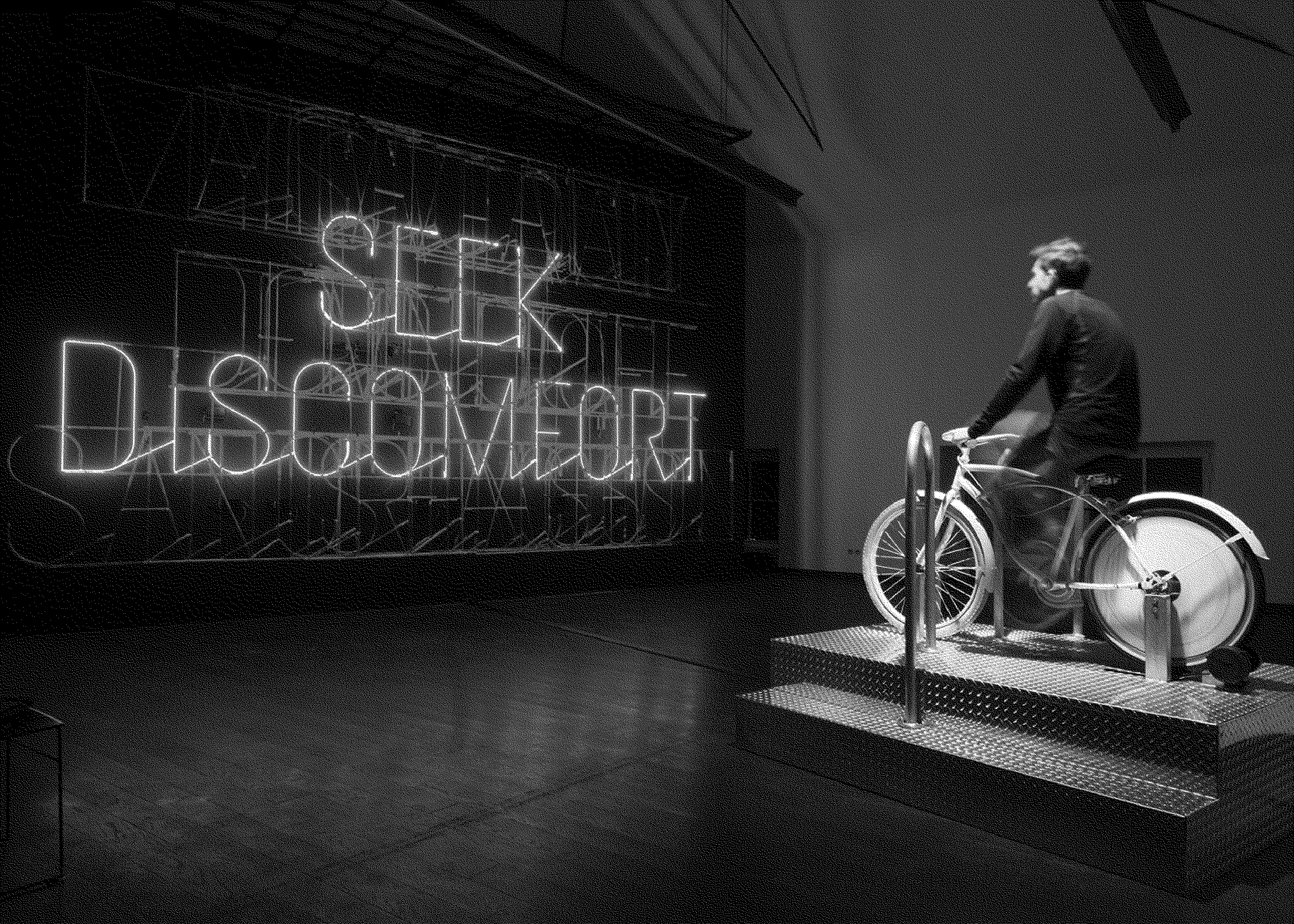

The unknown, the spontaneous, the unexpected or random event played a vital role in the creative process for many artists and in art movements such as Fluxus, Dada, and Situationists. For example, fluxus was heavily influenced by the ideas of John Cage, who believed that one should embark on the piece without having a conception of the eventual end. For Cage, it was the process of creating that was important, not the finished product. How did chance remain a key strategy in his work? From ‘Origins of the Fluxus Score’ from Anna Dezeuze the text ‘Chance and Choice’ points out at the very form of the work which reflects the process by which it was created. ‘The aim was to eliminate the subjective point of view of the author’ and therefore they introduced random chance processes. For example to determine the organization of sound ‘events’ within a time structure, Cage used to list in a chart all the event materials which he wanted to use and then would throw dice in order to determine their characteristics and order; (sometimes using the Chinese book of changes — I Ching). Cage’s work reveals an important use of chance techniques within the creative processes, these methods influenced many other artists like George Brecht, Mac Low, La Monte Young… In Chance Imagery, Brecht uses coins, cards, dice, roulette wheel, to determine how the performer will be involved.

Fontana Mix, John Cage ©

The Dada movement’s main influence was Marcel Duchamp, who had originally been active within ‘readymades’, Duchamp created a series of artworks consisting of found objects, thereby negating any need for traditional artistic skill. For Duchamp, it was about challenging the art and culture, like Cage, doing something that no one else had done before. If I describe art as “experimental” in the large sense of the word, people might not refer to a formal testing procedure but to the inclination to test social boundaries and conventions; in other words, to contemporary art’s roots in the history of the avant-garde. During my research, I tried to reposition experimental periods and tried to understand how and why experiments started?

The role of the experimental has been located within the territory of the avant-garde, operating outside dominant traditions. The term ‘avant-garde’ (from the French ‘advance guard’ or ‘vanguard’ literally ‘fore-guard’) is traditionally used to describe any artist, group or style, which is considered to be significantly ahead of the majority in its technique, subject matter, or application. This is a very vague definition, not least because there is no clear consensus as to ‘who’ decides whether an artist is ahead of his time, or ‘what’ is meant by being ahead. To put it another way, being avant-garde involves exploring new artistic methods, or experimenting with different techniques, in order to produce something original, something brand-new. The emphasis here is on design, rather than accident, since it seems doubtful that a painter or sculptor can be accidentally avant-garde. But what constitutes ‘better’ art? Does it mean, for instance, painting that is more aesthetically pleasing? Or more meaningful? Or more vividly colored? The questions go on and on!

Perhaps the best way of explaining the meaning of avant-garde art is to use the analogy of medicine. The vast majority of doctors follow mainstream rules when treating patients. Similarly, most painters follow traditional conventions when painting. However, a very small group of doctors and researchers experiment with radically new methods — this group corresponds to avant-garde artists. Most of these new methods lead nowhere, but some change the course of medicine forever. The term was reportedly first applied to visual art in the early 19th century by the French political writer Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825), who declared that artists served as the avant-garde in the general movement of social progress, ahead of scientists and other classes. However, since the beginning of the 20th century, the term has retained a connotation of radicalism, and carries the implication that for artists to be truly avant-garde they must challenge the artistic status. Which is, its aesthetics, its intellectual, its conventions, or its methods of production.To experiment is to extend the work beyond the limits of newness and play it out into the territory of the unknown. Everything touches ‘experiments’.

Or better to say it this way — experiments touch everything. From literature, theatre, dance, music, to cinema, photography, actually including pretty much every form of art. I would like to introduce a few examples where experimental took place in the avant-garde territory.

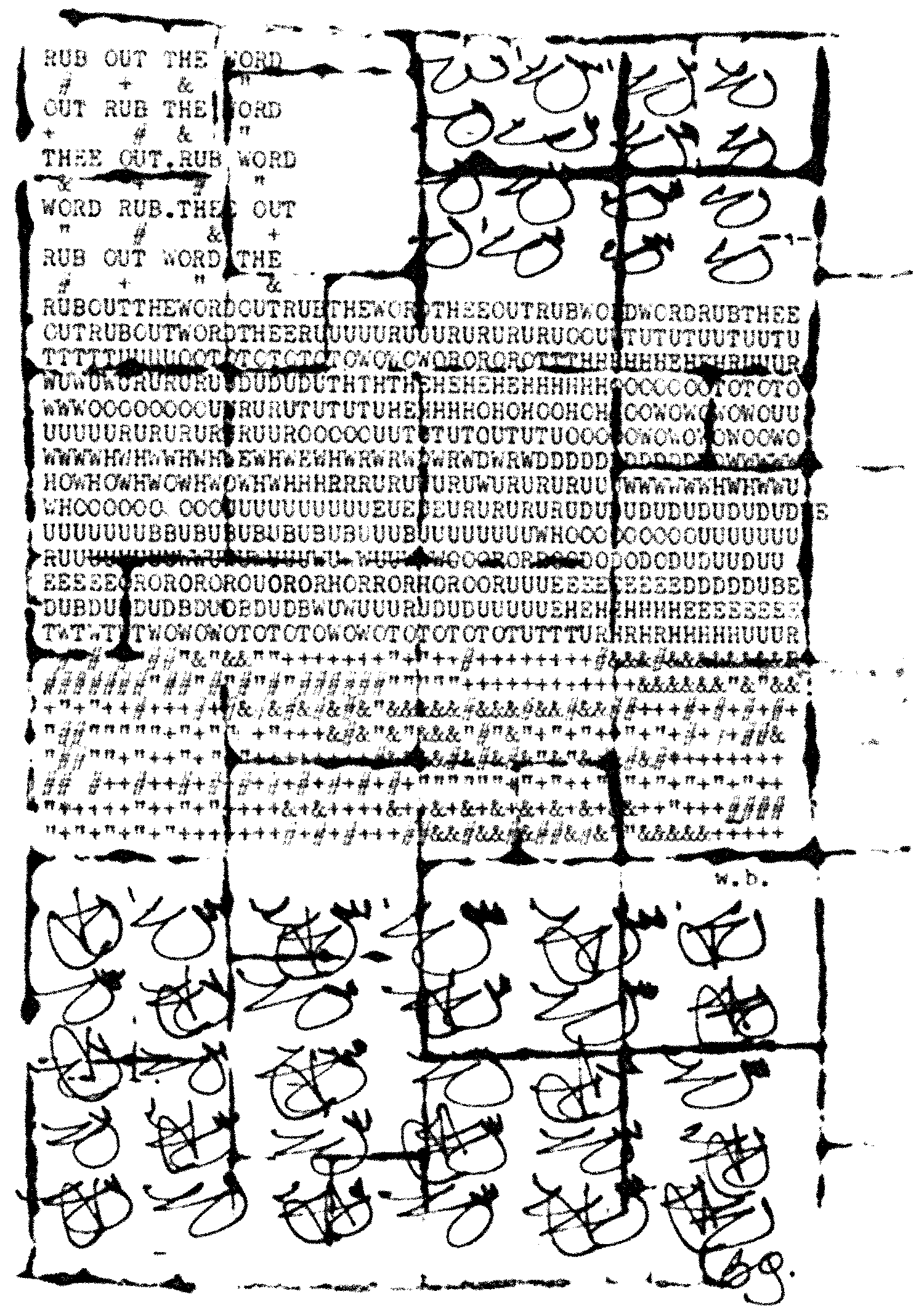

In literature, the writings of James Joyce and ‘cut-ups’ of Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs (1959) were experimental in the way words and language were deconstructed to create a fragmentary non-linear approach to the contemporary narrative form. Gysin introduced Burroughs to the technique and later they both applied the technique to printed media and audio recordings in an effort to decode the material’s implicit content, hypothesizing that such a technique could be used to discover the true meaning of a given text. In this example, chance or the unexpected event lies in their technique. The tools used are the language deconstruction which Burroughs and Gysin use methodically in order to encounter chance.

Visual Art of William S. Burroughs ©

In music, the composer John Cage’s with 4’33” (1952) — the score instructs the performer not to play their instrument during the entire duration of the piece throughout the three movements. The piece consists of the sounds of the environment that the listeners hear while it is performed. 4’33’’ received many critiques describing the work of John Cage non-musical. Ever since the piece remains controversial, and is seen as challenging the very definition of music. John Cage speaking about the premiere of 4’33’’ says:

In a 2013 TED Talk, philosophy professor Julian Dodd argues that 4’33” is witty conceptual art, but does not meet the criteria for it to count as music. 4’33” challenges the listener to question what the nature of music is. Paul Bloom puts forward 4’33” as one example to show that knowing about the origin of something influences our opinion about it as “that silence is different from other forms of silence”. |24||24| Paul Bloom, Paul Bloom: The origins of pleasure - Talk Video. Reviewed 12 November 2015. ted.com.

In cinema, the exploratory Dada films of Lars von Trier and the ‘Dogme95’ movement (1995), whose manifesto called for democratization of cinema; for example, films were to be made on location with hand-held cameras; or another rule that the director must not be credited. These were rules to create filmmaking based on the traditional values of story, acting, and theme, and excluding the use of elaborate special effects or technology. It was an attempt to take back power for the director as artist. Such technique can be compared as a method using certain rules as tools to frame their work.

In photography, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) was fascinated by the expressive possibilities of the photogram — photographic process of exposing light sensitive paper with objects overlain on top of it. While this simple process was practiced by photography’s founders in the nineteenth century and was later popularized. Avant-garde artists of the twentieth century revived the photogram technique as a means for exploring the optical and expressive properties of light. Moholy-Nagy ambitiously suggests that photography may incorporate, and even transcend, painting as the most vital medium of artistic expression in the modern age. He experimented with the medium until 1946.

Gelatin silver print photogram, László Moholy-Nagy ©

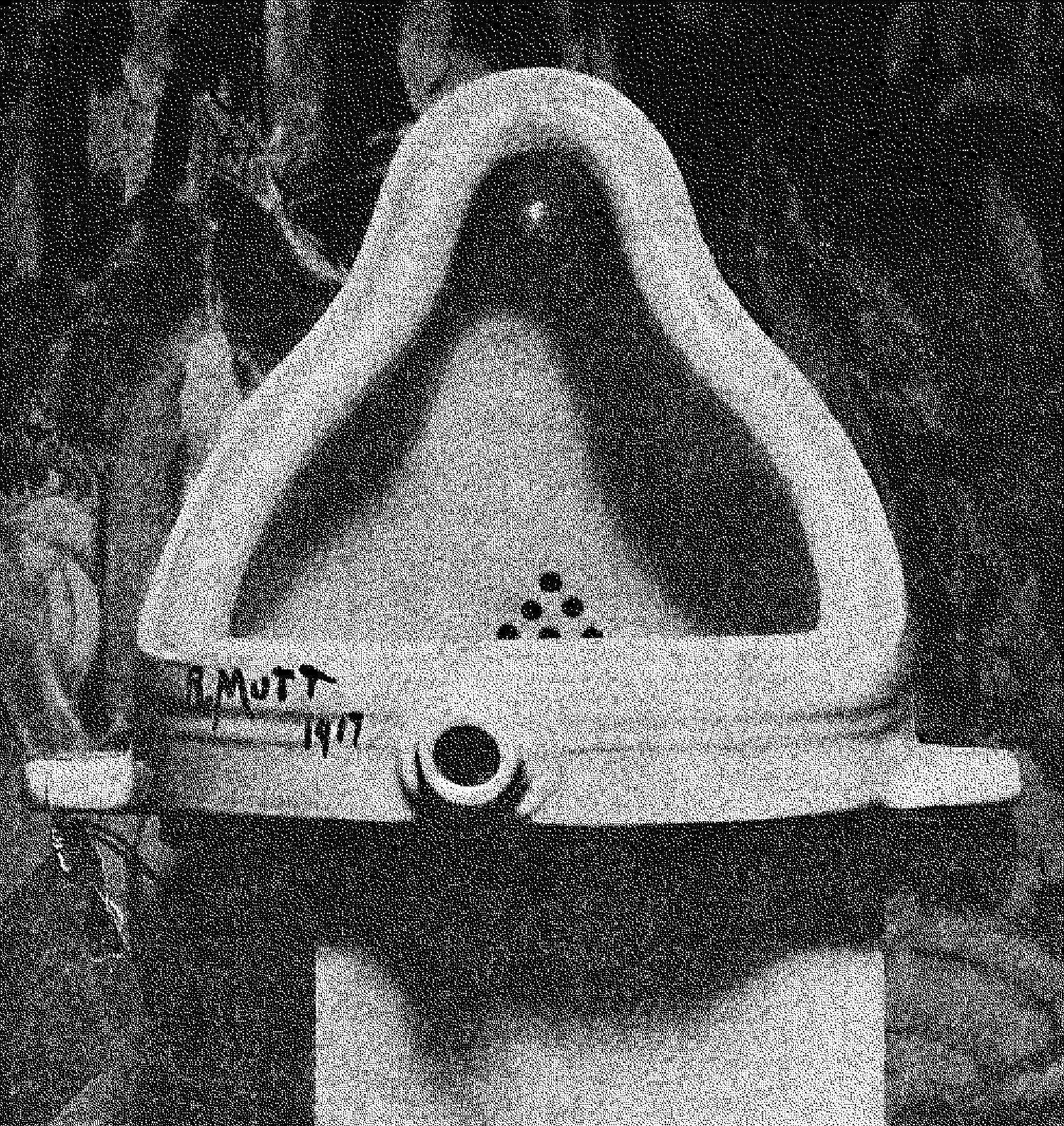

In visual art, the most prominent example is Duchamp’s submission of Fountain (1917) to the Society of Independent Artists — Fountain is a porcelain urinal, which was signed ‘R.Mutt’ and titled Fountain. Duchamp has produced relatively few artworks while he remained mostly distant of the avant-garde circles of his time. In a BBC interview with Joan Bakewell in 1966, Duchamp compared art with religion, whereby he stated that he wished to do away with art the same way many have done away with religion. Duchamp goes on to explain to the interviewer that “the word art etymologically means to do”, that art means activity of any kind, and that it is our society that creates “purely artificial” distinctions of being an artist.

Fountain, Marcel Duchamp ©

I will conclude that avant-garde movement offered critiques to the mainstream, challenging conventions; but developped new ways of seeing. Indeed, the avant-garde may have rejected existing traditions or tendency, but it also took forward ideas and developed original positions. Some may argue that a handful of examples will transcend time, but what is experimental at one historical point or in one cultural context might not be considered experimental in another. The avant-garde has been an insecure period and its boundaries constantly change as it searches for the next new thing. I believe that today more than ever, we are in perpetual search of this newness — this thing that hasn’t been done or seen before. As I am writing, I wonder how to achieve such a goal while it’s relatively easy to focus on what we know, but we can not think of things that we do not know.

III. II. II. Serendipity

The word ‘serendipity’ or the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident was first coined in 1754 by writer Horace Warpole (1717-1797) in a letter to his friend. The phenomenon he named was inspired by a Persian fairy-tale ‘The Three Princes of Serendip’, who go on a journey making discoveries, links, and associations, solving problems through their wisdom.

Serendiptology (the study of serendipity) is the process of making and developing unexpected yet intuitive discoveries, extending to all creative efforts. This method has been developed in order to structure yet liberate the process of artistic practice. Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) describes serendipity with an additional state of receptivity. In the field of creativity, being prepared, curious and open-minded, about the world can provide a useful process to enable a leap of the imagination beyond rationality, to develop intuition and ideas of consciousness.

This particular approach to discovery, and of unexpectedly finding knowledge, material possibility and acting on that to positive effect, could be defined as Serendipity. And as such used as a method in any artistic field. If discovery were made by chance or accident alone, any discoveries of any kind would be made by any inexperienced researcher. Starting to dabble in research as by Claude Bernard (1813-1878) or Louis Pasteur (1822-1895). I believe, the truth of the matter lies in Pasteur’s famous saying “In the field of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind”. It is the interpretation of the chance observation which counts. The role of chance is merely to provide the opportunity and the designer/researcher has to recognize it and grasp it.

Exploration does not just present new surprising routes but sometimes the accidents in a creative process show an entirely new conceptual map. In the scientific world, there are many examples of these kinds of happy accidents. To name a few, this was how Alexander Fleming (1881-1955) who invented the penicillin in 1928, Wilhelm Röntgen (1845-1923) invented the X-Ray in 1895, and Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) became world-famous from the daguerreotype in 1839.

In Daguerre’s case, it was due to a spilled jar of mercury in a cabinet in which he stored silver plates, after which the mercury produced a perfect image on the plates. Wilhelm Röntgen was doing experiments with vacuum tubes when he accidentally discovered a fluorescent effect, caused by the X-Ray on a piece of cardboard that was only there to protect an aluminium window. In Alexander Fleming, it was mould that accidentally infiltrated his lab through an open window. Of course this examples apply to science, but between 33% and 50% of scientific discoveries are unexpected. Often scientists call their discoveries ‘lucky’, and yet scientists themselves may not be able to detail exactly what role luck played. But what is crutial in the work of scientists is to experiment. In fact, to experiment is the key to any unexpected discoveries, (without forgetting to have a prepared mind.)

David Carson suggests that the essence of experimentation is going against the prevailing patterns, rather than being guided by conventions. This statement is in fact opposed to the scientific usage of the word. In the scientific field an experiment is designed to add to the accumulation of knowledge. In design, the results are measured subjectively and designers have a tendency to go against the generally accepted base of knowledge.

I will conclude this chapter by relating to the research method of a scientist and a designer. Both rely on experimentation as a method to find unexpected discoveries. Like Kurt Schwitters once said:

In fact in the field of design the fate of experimentation is a permanent confrontation with the mainstream and serendipity can be approached as a tool for such method.

♠ CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

We learned from the role of chance in relation to the creative process, that a certain level of knowledge is necessary. As a matter of fact, the knowledge we gather in the preparation stage are meant to construct new ideas. Therefore the research and other intellectual resources are essential in order to establish chance. In contrary, we know that creative breakthroughs are not always the product of the most expert thinkers in a discipline. But how do we find the balance between these two? The balance is in fact set between the conscious and the unconscious stage. By gathering the knowledge in the first place, it is only in the period of unconscious processing that the role of the idea can be generated and be carried further. From this point on the role of connection making is fundamental. Like intuition and imagination for example. These two aspects play a dominant role consisting in linking up ideas whose connection was never expected before.

So does chance appear between this balance? Not only. Chance or unexpected surprises emerge from experimentation which is the next phase . As William Blake says “The true method of knowledge is experiment”. Genuinely experiment will bring discovery since experiment is an attempt at something new or different. But do these stages leave apart from each other?

More interestingly, these different stages of the creative process should always be overlapping each other as we explore different problems. A designer reading a newspaper, a scientist watching an experiment, or a business man going through his morning’s letters, may at the same time be incubating on a problem which he proposed to himself a few days ago, be accumulating knowledge in preparation for a second problem, and be verifying his conclusions on a third problem. Even in exploring the same problem, the mind may be unconsciously incubating on one aspect of it, while it is consciously employed in preparing for or verifying another aspect.

With attention to construct unexpected outcome, the creative process should be design in such a way that the interplay of the different stages should always be in constant move. Interfering these different aspects of the creative process can influence discoveries. And that is another reason why in the field of design, designers should attempt at embracing every aspects of the profession. In fact, being prepared to move from a stage to another — interlacing between preparation, incubation and illumination. To wrap it all up, I would like to perceive chance not as a result of a method but as a strategy to a method. But at the end we can ask our self, Could chance be establish without any creative process? We are after all well prepared to perceive chance coming. So does chance really exist? Or are we the articulation of chance?

□ SOURCES

BOOKS

MAGAZINES

ARTICLES

DOCUMENTARIES & FILMS

The images used in supporting this thesis do not belong to me, nor were made by me. All acquired images have been acknowledged appropriately in the above section.

■

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank my thesis supervisors in alphabetical order Nick Axel, Marjan Brandsma, Eric Schrijver and Dirk Vis.

I would like to thank particularly Joseph Hughes for taking time and correct my thesis.