Reimagining music's visual context anno 2016

Introduction

With the shift of sound waves turning into zeros and ones being behind us, the visual presentation of music towards the consumer has done the same. This is not a surprise knowing the fact that our lives and our second lives in the digital realm are starting to overlap more than ever now that we have reached a point where new generations are growing up in a fully digitalized world. Physical magazines stop the presses and continue their journalism on the web in a digital form. But most of all has the emergence of social media created an interesting new platform for artists to digitally represent themselves. Media like Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, Soundcloud, Tumblr, YouTube and Twitter have all created new stages for the artist to build a character and personality. Artists and musicians are becoming a factor the user can relate to and define itself with, within the digital realm. An important aspect of these media is that they are all almost completely visual.

This is especially creating interesting developments for the distribution of music in the context of social media. Obviously music is perceived sonically, but the perception can change a lot in relation to a visual context. The music is brought to the user through the screen. The screen functions as a new layer of your existence, actually replacing the one you are currently in plus the distractions of the real world. With this in mind: how does a musician gain the user's undivided attention, if at all? As Lev Manovich states in The Language of New Media, “the computer screen displays a number of coexisting windows, of which not a single one completely dominates the viewer's attention.” On social media the music presented through the screen is only a visual compartment, tempting the user to click the link to the actual music, adding even more distance between the music and receiver.

With rapid technological changes like social media and the screen in mind, I wonder: “how does this alter the way music reaches us?” How does this change the function of a musical artwork like the album cover? Interestingly enough we seem to be finding ourselves on the brink of a turning point in the visual representation of the musician, both looking back and forward in time. How has the way the artist presents him or herself to its audience changed in the last couple of years? And even more important: what is going to change hereon after?

Too many bedrooms

The digital revolution has caused production of music to turn completely digital. This means that any upper middle class kid with an internet connection and a torrent client can and will get into music, instead of stocking shelves in the local supermarket. With the internet both enlarging audiences and illuminating the way to the right scenes for the right sounds, a lot of young emerging artists have gotten the opportunity to reach overnight success with their digital creations, in the form of 5 digit + “play” and “like” counts. The reach for attention on the digital platform has become a championship of some sort. Rather than making music for the music’s sake, a constant demand for positive digital feedback seems to be the drive for young bedroom producers to make music more and more. This has two major consequences on the market:

- The music market is oversaturated.

- The period of time in which musicians seem to be making and releasing their new music has decreased immensely. Sounds and genres are shifting faster than ever, which makes it hard to keep up for both listener and musician.

Besides huge amounts of people trying to make it in the same business, within different subgroups, they're all making the same music. The internet has helped to create an environment that seems to be giving new artists the illusion that there is no time and space left for creative exploration, while in reality this is the main thing that potentially separates you from the masses. And even if you do manage to distinguish yourself, you will very likely drown in the overflowing stream of uploads to the web.

To stand out in a crowd of new generation musicians screaming for “views”, “likes” and “shares”, apparently you have to be distinctive on another level besides being so sonically. There has to be another factor that makes it appealing to engage with the artist, before the screen presents the user a place where he or she can interact with the music. As stated earlier, a new level has been added to the representation of the artist, which is the online presence (or absence). Not only should the artist make good, appealing, progressive and/or interesting music, the way it is presented should trigger the user enough that he or she actually decides to stop scrolling. Like back in the days the album cover would let you stop browsing when going through vinyl records at the local record store. It’s often even the case that the visual presentation of the music is much more appealing than the music itself and keeps the viewer interested anyways. This is when the strength and deceiving nature, but also the importance, of the visual truly becomes clear.

Is it because of this online presence that people tend to grasp to the physical or even the old? When music became digital and the Compact Disc (CD) became a mainstream medium (and again after the downfall of the CD) you could clearly see a revival of interest in vinyl as the ultimate medium, for several reasons. Firstly a lot of people would agree with the fact that the deep sound of the bass on a vinyl is of higher quality in comparison to an mp3 and secondly the warmness of the needle touching the vinyl must give some sort of feeling of nostalgia to some older listeners. But is there nothing more to it? Maybe the fact that the physical property of an album itself, i.e. that you can hold it and give it it’s own place in your room, something you can perceive physically and not only sonically, gives an extra layer to the experience of the concept “music”.

If the digital platform is the future of our visual culture to come then why are all digital artworks still mimicking the vinyl packaging in its square shape? Surely it's not because of the fact that Instagram would only let you upload square pictures until recently. Perhaps the square record had become a formality in the music culture and just like any physical property turned digital it stuck to the visual standard of skeuomorphism used in interface design in a very subtle way.

Take for example Apple's overly excessive use of skeuomorphism up until iOS 7 or the endless radio skin designs1 available for Nullsoft’s Winamp Media Player. Now that Jonathan Ive however made sure that every last bit of skeuomorphism has been beaten "flat" (and of course the rest of the companies followed) would you not say it's time that the digital records sleeve takes on a new shape? It would be a waste of possibilities if it didn't.

Music loses shape

“In an ancient past graphic design and music used to be very close. Album covers and far reaching projects with artist-performers would take the designer out of a boring deadlock of annual reports and corporate identities. The invention of independent pop music was the invention of another type of design. Now once again there is a closeness between both worlds but they have changed. Music has become an art form that is also one of the world's most exciting emotional currencies and design has become so fluid as to invade every field, wanted or unwanted, in search for meaning.” – Daniel van der Velden, Vinca Kruk - Metahaven.

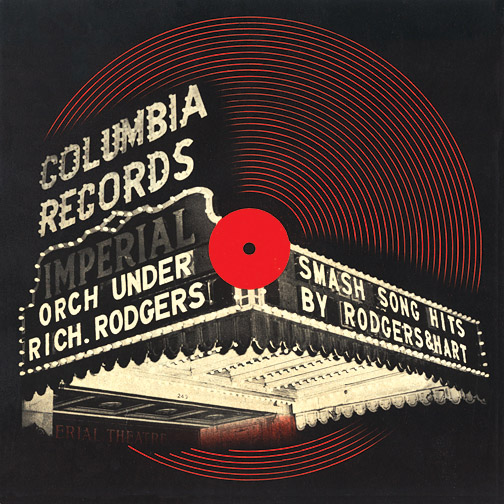

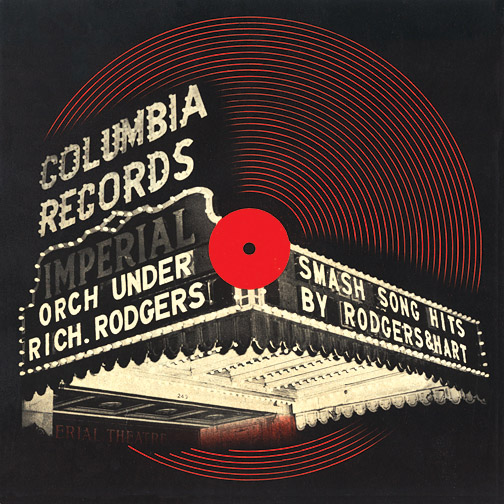

This ancient past Daniel speaks of must definitely be around the year 1939, when the first album cover ever2 was designed by Alex Steinweiss, art director and graphic designer at Columbia Records, commencing the first promotionally visual era in music ever. These were much simpler times in terms of artist representation or music in general for that matter. By that time, the bakelite phonograph disc had been in production for quite some time and it wouldn't be that long (9 years ) before the first vinyl would have been introduced to the world. What is of big importance for this period of time in music is that it was (especially compared to now) much more of a performative medium. As most people know, musical reproductions in the form of discs at that time weren't of a quality that would create a 1:1 replicate of the original recording of a song. Therefore to properly experience the music you wanted to hear you would have to go out to an event and see the band, or cover band (which was actually “a thing” existed around that time (I know)), making music itself dominantly performative. Before that time the only role design had in relation to music was to promote actual performances in the form of posters and pamphlets, rather than getting the audience to buy records. In a way the performance was the visual / the promotion. And even later, around the 60s, when the record industry was literally transformed because of the LP sales and the business that it had created over time, besides making waves through radio the only way to get any feeling of interaction with a musician was through actual concerts. There was literally no choice for both the artist and the audience. Concerts were the standard and the performer had to do the shows to sell the records.

However in the 70s, an early form of something that is becoming the standard in obtaining music in current times pops up. Besides being sold legally, cassette tapes had become a way to cheaply and easily reproduce (and illegally distribute) popular music. It's an early sign that shows that the more flexible the medium becomes, the higher the chances become of it being pirated or being used to other ends than originally intended.

This is why the U.S. Congress declares sound recordings worthy of copyright protection in passing the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment to the 1909 Copyright Statute. Even though this amendment was proposed largely in response to the record industry's complaints of vinyl bootlegging, the implications of the amendment are applied to the burgeoning recordable audiocassette market. The youth had been taping and swapping their favorite albums and the record industry advocated a tax on blank cassettes to make up for the lost profit from tape bootlegging. At that time the music sales were still growing. In the late 70s however, when sales started dropping and the introduction of the Walkman had turned the tape to a main format of music, piracy had become a real issue and an industry wide campaign against home taping had emerged.

Ironically enough, during the emergence of piracy within the industry, music is for the first time introduced to the consumer in a digital format when Philips and Sony announce the Compact Disc in 1978. The CD heralds the temporary death of vinyl (until it's sudden revival in the contemporary digital age) and the invention and emergence of the internet. The CD and the internet together combined created the mp3 in 1990. It appears to be the root of the state that music representation currently has gotten into. With the internet as an uprising platform in popular culture, things like music streaming and online music distribution arise which eventually leads to the ever ongoing fight against internet piracy, commencing in 1998 by the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America).

On the road to making all music as distributable and profitable as possible, the developments in mass production of music towards contemporary times seem to have resulted in the opposite. Reproduction has become so easy that piracy seems to have gotten the overhand and made profits drop tremendously. This has caused a huge shift in the position of the musician, both economically as well as artistically. The record sales don't seem to be the leading figure in the industries’ income anymore and instead of playing shows to sell records, it looks like the musician has to release records in order to do shows, performances and concerts. A new layer has been added to the promotional hierarchy.

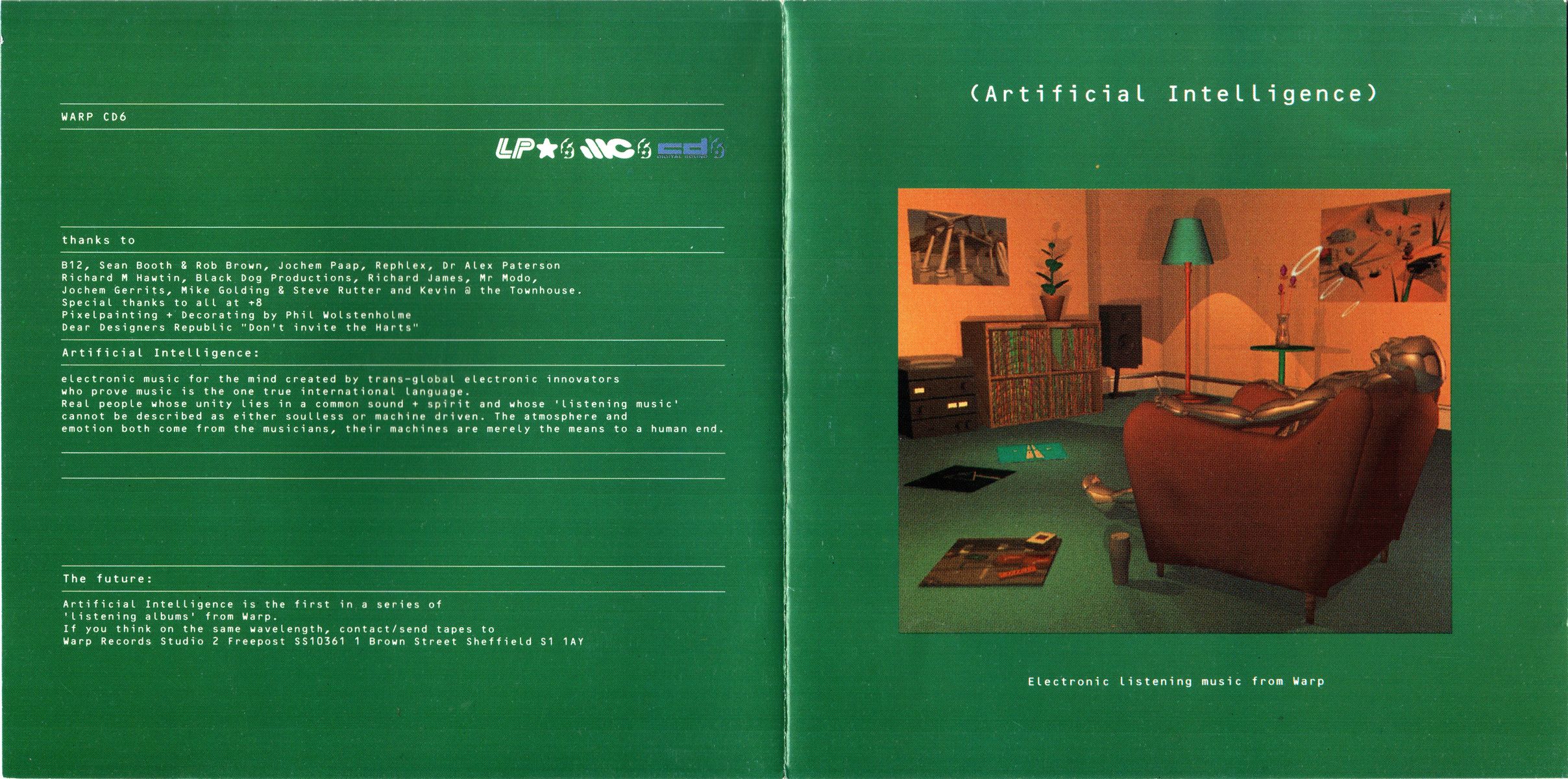

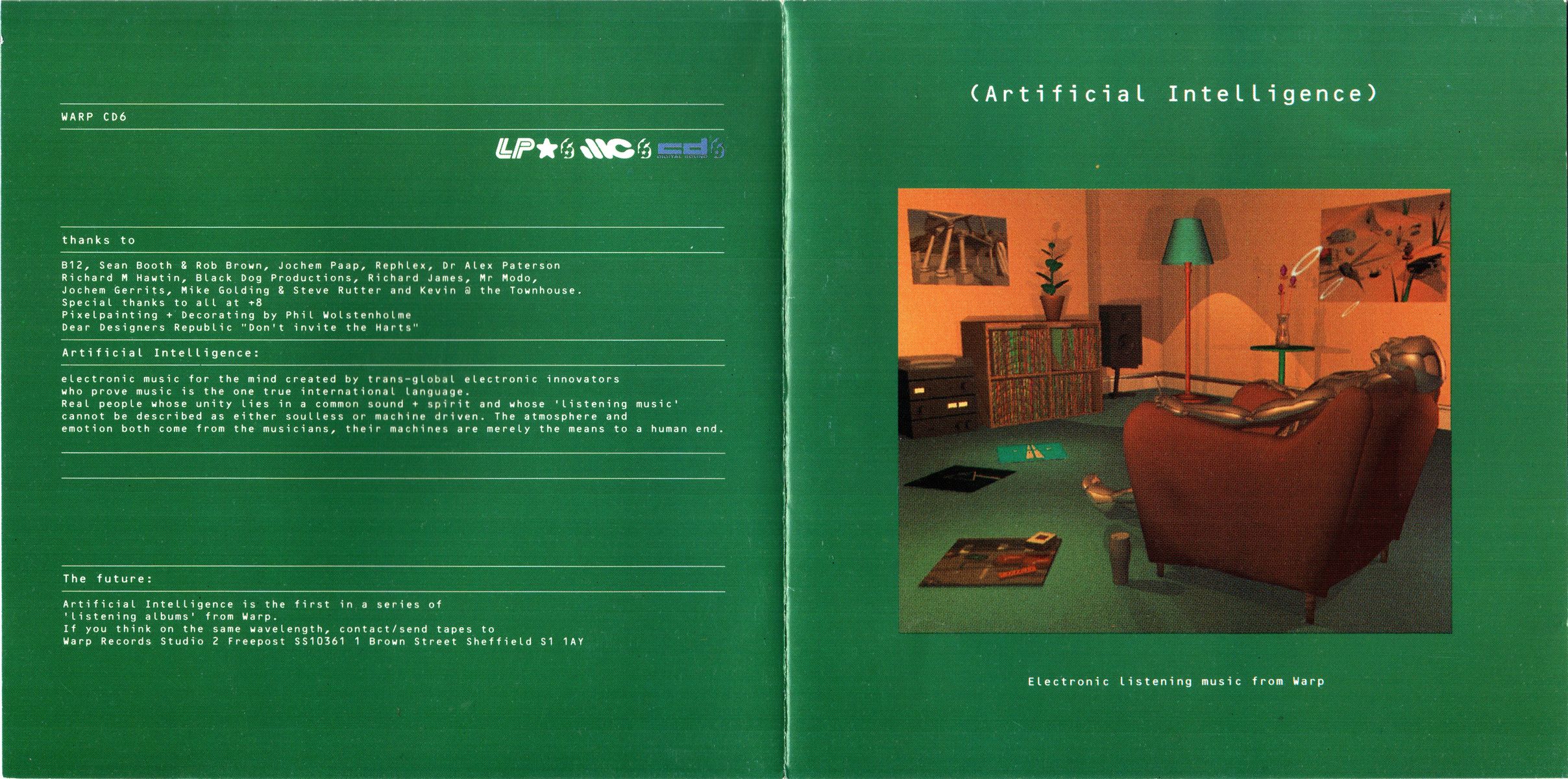

Of course not all music was made for performance though. For example WARP’s Artificial Intelligence series from 19933 announces electronic music for a non-club context very early on. The iconic album cover picturing an android listening to music in a living room shows an understanding that the context in which the music is perceived is crucial to the experience but also illustrates a reaction to the performance oriented state music was into at the time (and about to get out of). The promotional hierarchy has also been altered in the sense that in some cases (for some artists’ or genre’s) certain ways of musical expression have turned into distinct forms of musical experience instead.

As discussed earlier, the musician is trying to find a way of online representation as a part of his or hers success. Where the performance was a promotional thing back then, the (social) media functions as a hugely promotional tool nowadays, creating interest for the music, which then lead to live (paid) performances or another musical expression respectfully to the artists’ musical context. It doesn't come as a total surprise that a rising number of artists and labels decide to give away digital records for free in the shape of mixtapes (take a look at Datpiff.com on which basically all rap careers are born through successful free records). In a way it’s the industry admitting or even surrendering to the idea of the record on it’s own not being profitable anymore. Thanks to the digitizing of everything, music has become more and more a mediated medium rather than a performative one and the musician finds itself on a social platform rather than on an actual stage

The social artist

"It's free and always will be". That's what it (for some reason still) says on the Facebook sign-up page. The intentions are always good, initially. Facebook would become the number one platform to keep your network of friends and interests together in touch in one virtual "location". The timeline would become a space in which all of your friends and interests’ activity would be chronologically summarized.

Soon however the timeline turned into a “feed” where posts would appear non-chronologically, sporadically and finally based on "your interests". Algorithms made their entry and slowly with that came paid posts. Basically what this means is that if your post doesn't get enough interactions (“comments”/ “clicks” / “likes”) within a small selection of your Facebook friends in its first moments of its existence, it won't show up in the rest of your friends' feeds. And the same counts for artist pages and fans, unless, of course, you sponsor your own posts. The more you pay, the more it's shown on people's timelines. The idea is for your feed to show only “good” content. Good content is however highly subjective which turns it into “most liked” content, which again basically means the content with the most attention or/thus the content that has been paid for the most.

Regarding Facebook or any other social media platform for that matter people always quote the widely used phrase: “if you're not paying for it, you're the product” – Andrew Price. However you can now decide whether you want to pay Facebook, which, I guess, makes you both a product as well as a consumer. We are now officially products of ourselves, thanks to social media.

And even outside Facebook the business that exists around online popularity continues in the form of websites offering fake likes and followers. “Share Castle”, a record label which entire existence is based on this phenomenon, was brought to my attention by a friend of mine. It’s a self-proclaimed “label for critical pop in the network age”, that seems to be generating attention by taking advantage of the possibilities of getting artificial attention nowadays. It's questioning the new functions of the web by experimenting with its possibilities. The real, non computed attention that it seems to be getting, however, is either people understanding the art school project or people sharing sharp project analysis like:

“this is terrible. I see why you had to pay for followers.” - Jason Temple

But let's not drift away from the main subject in question too much. The complexity of the interaction between user and viewer described above doesn't mean that everything is doomed. In fact it should push us to be more creative with the content that we share. As a result a lot of artists turn into meme pages , that share funny images to generate more audience before they even think of sharing music or “Like To Download” , which in it's turn turns their music rather into a currency for social media traffic.

But there are more ways to generate the right attention for your music. The last two examples (sharing meme’s and like to download) actually make your audience much more unfocused and unclear. Your fans might not even be fans of your discography and only follow you because you said something funny once or liked this one future bass Aaliyah edit you posted on Soundcloud, because you didn't share any new sounds for like a week. Congratulations you're not a musician; you're a meme now.

I'm not saying all the musicians that didn’t turn into memes are interesting online presences, though. Still, there's a serious pattern to be found in the way artists behave on the internet in the light of events in their musical career. The first and most important feature, one many seem to be taking as a standard, is that it's on the web. The guidelines of the tool used on their turn create certain nearly pre-generated approaches to the artist's online behavior. Whether it's Facebook or Twitter, the artist (read: generic artist) seems to feel it's mandatory to come across extremely enthusiastic about the event or opportunity in question. The artist has set certain goals to reach within its career that are often the same as other comparable and somewhat bigger artist's goals. Posts, in which the musician has a new announcement to make, have to start with: “Very excited to finally announce to you guys that...”4. I could make a whole list of unwritten rules on how to fit in as a generic artist on social media but I think you get the point. Musicians tend to fill up an existing platform with other people’s words in a ready-made context rather than create their own. The music should be good enough, right? Well, since you’re asking: no, the music is good enough to deserve something more than just a quick Facebook post.

The Website As Digital Mirror

You could look at the array of social platforms and blogs as being different "locations" that the regular internet user can quickly shift between, during their daily time online. Something announced on Twitter can get picked up by followers and blogs and can be spread in other places like Facebook or Soundcloud or any other comparable platform. People tend to limit themselves to the mainstream social media to get their work spread however. While a location (website) outside of these media is in no way subject to any limitations to the visual side of things, if any side. The dedicated website can create an almost immersive experience, be it informative, visual, audio/visual or even interactive. Just as any other media output (like a video clip), a website can be exciting enough to get picked up by third parties and be premiered by any big outlet. This is the big difference between a post and a website.

Take for example Rustie's Green Language record, released through Warp in 2014, which was streamable online by engaging in a first person video game. Just like the music, the game tends to create a virtual world and context curated by the musician. The further you get into the game the more songs you get to hear from the new record. It almost reaches a point where it's uncertain whether you're actually playing for the game or the music. Perhaps this is what is supposed to be achieved through the dedicated platform. Even though the visual (or virtual space in this case) is a response to the audio primarily, the audio/visual almost functions as a "gesamtkunstwerk", where the visual is equal to the audio. A virtual world in this sense means that it's just you, the game and the music. What is specifically important about this project and its visual is that a game engine originally is not something that is necessarily related to something musical, but was used anyways cause it showed to be the perfect platform for a record like this. However some online platforms even take it as far as bringing actual physical locations together on digital space, through streaming.

The famous party-streaming platform Boiler Room and streaming party platform SPF420 show two extreme examples of this. It's platforms like these that help define certain musical niches, almost in a way that forums in the earlier days of the internet used to bring people together to discuss about any interest they had. However in this case it is done by creating temporary live streams happening cross-platform that gets the user to engage with both the music and live discussing it. Where Boiler Room streams from one location each time to their website online, a place where everyone can comment on the events happening at the physical party, SPF420 let's a line-up of artists spread over the world stream their show from their bedroom to a chat room, creating an online club environment almost.

A smaller project based in The Hague, called Hyphae, would even go as far as creating the last described concept and then project the whole thing in a club and invite people to enjoy the program in this physical space and streaming the actual crowd back to the artist as live feedback, blurring the lines between URL and IRL. Actually this is something that all contemporary technological developments (music related or not) seem to be heading their course towards to. Take a look at Holly Herndon for example, who, in collaboration with partner and conceptual artist Mat Dryhurst, connects the digital platform to the physical space in her shows. By creating live interactions5 between audience and visuals and adding Facebook profiles of people attending the event to a three dimensional digital space projected behind the musical performance, a new layer is added to the idea of the performance.

Obviously platforms like Boiler Room are a big part of an underground club culture and like no other do they get the sense of certain "scenes" and how artists make their way online. No wonder that they have a have some comment on the current state of music in a post internet age. “The internet has completely revitalized the underground culture. The democratization of access on a global scale has empowered musicians, freed information, started conversations, sparked incredible new levels of creativity, and put the jumper cables to an industry that was flat lining. It’s no longer potluck for who you know or where you’re at; the 1% have been rendered irrelevant. Good music finally reaches the right people. It’s better now than at any point in history, and we’re on track for it to get better and better. We’re part of a privileged generation. Some see the internet as a walled garden, where mastery of confusing new rules is required to stay afloat. We see the opposite: the barriers have been knocked down in every direction. The underground doesn’t just live online – it thrives there.”

In the process of writing this essay I had the chance to talk to the initiator of a new platform for music visualization called Whitestone (twice actually). The first time was when the project was in its recruiting stages. Roey Tsemah, the founder of the project, reached out to me and asked if I would be interested to try out his new platform as a musician. Later I got the chance to talk to him about why I wasn't extremely excited to engage into this. Actually, from the start I was skeptical about the whole thing. The website headlines “This is what music will look like in the future” (just the subject I'm writing about!). Roey explained to me that Whitestone would become the YouTube or Vimeo of websites/experiences. The idea of Whitestone is to create a social media platforms on which all musician’s that take part get their own page to do whatever they want on with predefined tools.

Like a bunch of its predecessors Whitestone seems to be aiming at reinventing the face of music all at once. Apple took it's shot back in 2009 when it launched iTunes LP , an extra iTunes feature that let's you create your own “rich, interactive experience” as your album artwork in iTunes. (Of course the fact that this was limited to iTunes already slowed down the process of taking over the music industry standards). Until recently popular music blog Pitchfork had their own platform called Pitchfork Advance that would play a yet to be released record alongside full screen animations, delivered by the artist. In a way that isn't much different from Pitchfork sharing someone else's streaming website on it's blog, but the template is an interesting take on the famous music blog album premiere preview stream. For some reason when I started looking up Pitchfork Advance however I couldn't find anything about it. My search for a platform’s approach to change the future of visually perceiving music ended up in something that was hidden, as if it never existed, or as if it knew that it wasn't really that new.

If you think about it, a YouTube for websites is in a way really the internet itself, in the sense that the internet is a collection of websites with Google as the search bar. A selection out of the internet websites wouldn't need a sole platform, it might just as well be a list presented on a blog. If you want to create/code an immersive experience, why not just make a self-serving website? And if it should be shared on social media, why not add a share button to that website? In this perspective Whitestone could also be a Facebook that only let's you like musicians and instead of artist pages you have websites that become artist pages once you scroll down. Of course it’s a step in the right direction and it sounds more exciting than Facebook’s musician page itself but it would only change a small part of those shortcomings. It’s still a prefab context for the musician’s music to exist in.

Either way it seems like I'm not looking specifically for a new social platform that gives the musician new templates to fill in with the same content. In the light of music's visual history and the most recent attempts of others to create a new thing or to reinvent the way that music is perceived, I guess the future brings a new approach to the things that exist and are within reach, much rather than an entire new thing, that will reinvent music.

Opposite of new platforms presenting new ways of doing the same things, there is something exciting called Saga v1.06 however. Saga is a framework that approaches content presented on the same old platforms but in a new way: “When you self-host your work and publish it using the Saga framework, every distinct plot where your work is shown becomes your space. You can choose to manipulate that specific space at your leisure, and those who share your work assume that risk when they choose to show it.” Saga gives the artists more control over the way their work is perceived on any place on the web. In this aspect it is really a new way of approaching media and is what any progressive platform should be: not a template.

In the process of design invading every platform, the musical visual seems to have joined in on the same development. Creative ways of reinventing media to amplify a musical project are making their first steps. Mainstream music in it's search for profit and distribution has always stuck to vinyl records, cd's, cassettes and the digital mp3 files and so on. But in more underground orientated scenes and companies, a not so obvious, sometimes even conceptually meta medium is what makes a project that much more significant.

Take for example "8 BIT MUSIC POWER"7, a compilation of contemporary chip tune 8bit music released on a Nintendo FAMICOM cartridge. The medium of choice is only playable through the gaming computer itself. What is even more interesting about this release is that it is the first time in over 20 years that a commercial release has taken place for that platform. This says a lot about the extremely flexible state of music at the moment and why something like this would not have been thought of before this specific moment in time. In that same aspect, music has also been released as USB sticks or SD cards8 very recently. Numbers' Sophie even went as far as releasing a record as a silicon product/object with a download code.

It is obvious that at this point Soundcloud is not anymore the only container for digital music to be presented in and digital files are even making their way off of the digital sphere. Literally anything can become the holder of a virtual piece of music if your project desires it. Not anymore is the medium just the carrier of the music files –digital or in waveforms- it has become “the outlet” that communicates the conceptual approach and/or message that comes with the musical project. Which is exactly why a medium like Whitestone for several new media is so confusing and should invite more artists to think of their work more as a complete package that can’t just be thrown into a predesigned grid on a free website.

The Performance as Landmark

There's a fine line between how physical performances get its share of online attention and the way that Land Art can create certain waves in the digital sphere. With the digital artist being omnipresent (and omni-generic) the physicality of things seems to have been forgotten. Often unconventional locations or places outside of the expected context of a discipline can emphasize the value of a project. Another aspect is added to the project, which is the travel, or even the quest, towards it. The unconventional location forces the beholder to break through the current of experiencing any art. In the most extreme form this could result in something like Francois Roche and Pierre Huyghe's “Train to nowhere” which resulted into a group of artists and art critics going on a one week train trip to a secrete location just to see a naked man run out of an igloo. Even though this project is a somewhat anticlimactic piece of art to some and not necessarily a piece of land art, it does emphasize and define the added value and anticipation of a destination that comes. In this aspect the musician can learn quite a bit of having their music take place outside of the conventional space.

Something similar in the music industry did happen when Daniel Lopatin also known as Oneohtrix Point Never announced his most recent LP through a big web of fake blogs, ambiguous videos and hints that would eventually lead to a collection of MIDI files functioning as a teaser of his album. Not to say that everyone who wanted to hear the album got involved into solving the puzzle, but someone at some time did it and the feeling of fulfillment has got that person excited enough to share the story with the rest of the world through the internet. The internet on its turn generated a ton of blog posts about the secret code behind the cryptical promotional campaign of Lopatin's record (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_of_Delete). This is not only a special approach to the extent of promotion of a record but even more importantly: it creates the background and context for the record without having to do another expected interview with a hip blog in which you explain the thoughts you had before “diving into the production of your album”.

Another, perhaps even more famous, example is how the most recent record of Aphex Twin was announced through a link to the deep web and a green blimp9 with just the Aphex Twin logo printed onto it. Not a single promo e-mail was sent out that day from the Warp offices, but still for a few days nothing but green zeppelins were to be found across Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. The non-announcement seems to be a tactical promotional decision, but often only seems to work for already famous artists. A green zeppelin with just any random internet producer's illustrator traced logo on it will at max result in a series of confused teens posting photos of it online with relevant jokes rather than excited Aphex Twin nerds guessing the releasedate of your record. That doesn't mean that your only option is jumping back behind the screen to open your Facebook's artist page though.

The distance between audience and artist again is being enlarged but this time it is turned into a crucial part of the project itself. Instead of pointing the media and fan base to the music, they were pointed to something else pointing to another thing, which eventually resulted into the journey to the actual music. A location away from the expected context is what changes the whole way the musical piece is perceived and this is applicable to every discipline within music.

As far as performance, this is something that also needs to be discussed. Since the performance or club is already away from the screen the standard (club environment) seems harder to break than you might think.

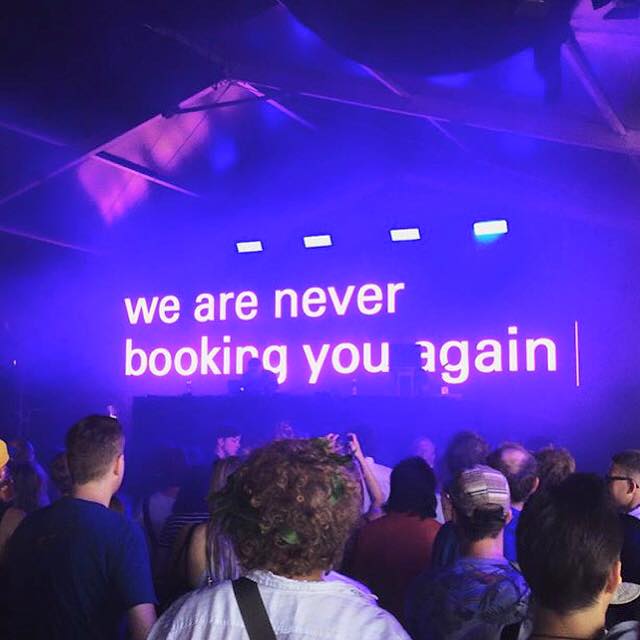

There are several ways you can approach the IRL performance differently, though. Take for example James Turell's10 work. James work is about light, scale, the perception of the environment and ones own body in relation to it but most importantly in respect to this essay: the location. The work is in the first place worth traveling to, but the travel adds value to that experience once you enter and see the installation. As if you haven't travelled to the installation itself: the travel helped you reach the portal that would let you enter the separate world that is created by mister Turrell. A perfect example of a location lifting a musical event beyond the performance itself would be how Red Bull Music Academy New York organized a Tri-Angle Records showcase last year in an old Wall Street Vault in the former J.P. Morgan building.. To some the line-up already was all-star enough for the event to be exciting, but it's not the first time that these artists names were lined up next to each other on one poster, probably not even the first time they played a show for Red Bull. So it is without a doubt the location that made this event specifically memorable. Interestingly enough one guy off the bill of this exact line-up, Evian Christ has recently started his personal search for how club nights can be more exciting and less generic. With his Trance Party-nights11 he pushes the bar of what a club night could (or in his view should) be, by experimenting with how nostalgic elements linked to the connotations that his music evokes can be of added value to the environment that everyone is familiar with from every weekend of there lives.

Conclusion

It has become quite clear that something that began with simplifying the distance between audience and musician has made everything even more complicated than it has been before, thanks to the way that new media have been adopted by artists. The combination of successful artists using an unwritten formula that younger musicians seem to apply one-on-one to their own practice and the ever diminishing space between their music and their audience made their product (i.e. their music) easier accessible. However, thanks to an overload of data and visual stimuli, it simultaneously becomes easier for the audience/fans to get distracted. It has only been so long for the new media to be settled and therefore it is not a surprise that the current state of visual representation of music happens to be the current state of visual representation of music.

Just like the standing out of the first ever full color cover design, the “standing out examples” shown in this essay are early cases of breaking through the current. And they seem to be having something in common. Unlike a lot of artists the specific examples seem to be remembering the visual oeuvre that music history has to offer, but also look forward in a sense that they embrace the new to empower the old. And if it doesn't embrace the old, it moves beyond the contemporary, aware of what it is and how everyone seems to conform to it. There are two big chapters to be looked at in current music history relevant to the subject in question if seen in broader perspective: the Performance itself and the Screen on which it’s presented. There is a period in between, but we are finding ourselves in a period that is moving beyond the latter, because of this handful of dear devil artists. The screen and the use of it seem to have settled in a way but the originally performative nature of music seems to be again dawning in the artists' minds.

In order to be progressive or engaging on a digital platform you have to consider actually stepping away from the platform or the screen. The work you present in the physical world always will find its way back to the digital world anyway, since the main use of social digital platforms is to share exciting enough real world stories to the social network you have achieved over time (so it seems). The problem lays within the fact that:

- The representation of the artist starts on the existing platform itself, which makes it hard for the content to leave that context once placed there.

- The user is not being challenged.

It seems that artists wants to create a connection between the user and the thing they present as easily as possible to access, which is basically the main ingredient for dull content. This also explains the existence of things like click bait (which on its own is already an argument for not sticking to this standard).

The music visual asks for a musician who takes the context in which it's music and its presence perform seriously. The musician should use this context to create the platform its music needs, rather than fil

ling up the empty spaces on the existing platforms. Everything is within the musicians’ reach and the re-contextualization of existing disciplines within the music world on and off the internet is a skill and tool that the musician should use complementary to his music.

The digital and the physical performative nature of music are both absent and present and must be taken into consideration when thinking of ways of presenting yourself. By now you probably know what the standard is for every aspect of musical representation. The only thing left for you to do is accept them as they are and move forward. It's not possible to define one shape of what the future will be of the music visual, but you can definitely determine what isn't.

Sent from my iPhone

Joeri Woudstra, 2016

TL;DR

The visual side of music has always maintained a conventional character. LPs and CDs are round and in order to properly wrap them up the corresponding packaging is square. With that the artwork too; nine out of ten times the artist finds itself performing his show at the end of the room lifted above the crowd and the video always seems tied to the square design and visual context that YouTube or Vimeo offer you. This is not the most interesting feature for such an autonomous medium.

Why doesn’t the shape adjust itself to the music? Ever since the beginning of the digital age a shift has taken place within the way we consume music. Vinyl records and cassette tapes are turned into zeros and ones; music literally has no physical shape anymore. The platforms on which music is being delivered to its audience have massively multiplied and even more important: renewed (think of thousands of professional and amateur music blogs and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat.).

Never before has music taken on such a flexible form as it has done now, since these new platforms and media have been accepted as a normal component of our current society and every day lives. Still, it seems to be the case that the new possibilities that have been created are not being used to it’s full potential.

The static printed album cover has turned into the organic and ever-changing computer screen, but the album covers are still square (and not moving?). Artists seem to be falling in a routine when announcing a new record; an exciting message on Facebook, an interview at this blog; a mix for that blog; a show at that cool festival.

How has the way the artist presents him or herself to its audience changed in the last couple of years? And even more important: what is going to change hereon after?

With every artist mimicking the next when it comes to promoting themselves on these platforms, the only way of keeping the users attention is to break through the generic standards. The musician should understand the context in which he or she and the music operates. Rather than filling in the blank spaces on existing platforms the musician can use this context to create his or her own platform, with the help of everything, thanks to the internet.

Sent from my iPhone

Sources

- Accessions. (2015, October 26). Circulation, Image, NORMAL, Self-hosting, Video. Retrieved from http://accessions.org/article/saga-v1-0/

- Aleksander, I. (2015, May 13). Oneohtrix Point Never unpicks the secrets of Garden Of Delete. Retrieved from (http://tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/05/13/francois-roche-pierre-huyghes-train-to-nowhere/?_r=0

- Allen, C. (2013, June 23). Happy 65th Birthday to the LP Vinyl Record Read More: Happy 65th Birthday to the LP Vinyl Record. Retrieved from http://nj1015.com/happy-65th-birthday-to-the-lp-vinyl-record-photos/

- Allwood, E. H. (2015, December). Prada Marfa: Ten Years On. Retrieved from http://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/27039/1/prada-marfa-ten-years-on

- Aphex Twin Blimp. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.stereogum.com/tag/aphex-twin/page/3/

- Art 21. (n.d.). About James Turrell. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/james-turrell

- Boiler Room. (2015, November 05). 5 Years of Boiler Room Los Angeles. Retrieved from https://boilerroom.tv/session/5-years-of-boiler-room-los-angeles/

- Bosma, J. (2011). Nettitudes - Let's Talk Net Art (Rev. ed.). Rotterdam, Nederland: NAi Publishers.

- Columbus Circle. (n.d.). 8 BIT MUSIC POWER [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/japanrealtime/2015/11/27/new-music-coming-for-nintendos-classic-family-computer/

- Dryhurst, M. A. T. (2015, October 26). Custom Text Overlay [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://accessions.org/article/saga-v1-0/

- Eyeszmusic. (2015, September 15). Eyesz [Twitter]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/Eyeszmusic/status/643793010736672772

- Jonathan Ive. (2004, February 12). Retrieved March 03, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonathan_Ive

- Lemaximonstre. (2015). Post-internet electro #HollyHerndon #øya2015 #APøyablikk [Instagram]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/6XinerKo-r/

- Lista de Radio din Romania in Winamp. (2013, February 01). Retrieved from http://sateliti.info/showthread.php/26725-Lista-de-Radio-din-Romania-in-Winamp/page2

- Manovich, L. (2002). The Language of New Media (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Masachussets: The MIT Press.

- Margaret, R. (2013, June). What is skeuomorphism? Retrieved March 03, 2016, from http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/skeuomorphism

- Martin, C. (2015, November 25). Inside Evian Christ\'s Trance Nation. Retrieved from http://www.thefader.com/2015/11/25/inside-evian-christs-trance-nation

- V Mensvoort, K., & Grievink, H. J. (2011). Next Nature (Rev. ed.). Barcelona, Nederland: ACTAR.

- Minsker, E. (2014, August 18). Aphex Twin Announces New Album SYRO Via the Deep Web. Retrieved from http://pitchfork.com/news/56341-aphex-twin-announces-new-album-syro-via-the-deep-web/

- Muggs, J. (2015, October 06). Joe Muggs on Warp\'s Artificial Intelligence series. Retrieved from http://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/essays/the-wire-300_joe-muggs-on-warp_s-artificial-intelligence-series

- Novin, G. (2013, November). Chapter 72: A History of Record Covers. Retrieved from http://guity-novin.blogspot.nl/2013/11/record-album-covers.html

- Parry, E. (2015, November 25). Inside Evian Christ\'s Trance Nation [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.thefader.com/2015/11/25/inside-evian-christs-trance-nation

- Parry, E. (2015, October 26). Inside Evian Christ\'s Trance Nation [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.thefader.com/2015/11/25/inside-evian-christs-trance-nation

- Price, A. (2013, February 27). User-driven Content [Blog comment]. Retrieved from http://www.metafilter.com/95152/Userdriven-discontent#3256046

- Red Bull Music Academy. (n.d.). TRI ANGLE RECORDS 5TH ANNIVERSARY. Retrieved from http://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/events/nyc-2015-triangle-records-5th-anniversary

- Ross, A. D. (n.d.). Deceptionista [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://p-a-n.org/product/adr-deceptionista-pan67/

- Ruiz, S. (2014). Throwback Thursdays: Artificial Intelligence – The Record That Launched A Genre [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.okayfuture.com/features/throwback-thursday-artificial-intelligence-warp-records.html

- Schoenherr, S. (n.d.). The Digital Revolution. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20081007132355/http://history.sandiego.edu/gen/recording/digital.html

- Steinweiss, A. (n.d.). Smash Song Hits by Rodgers & Hart [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/phono_technology4.php

- Taintor, C. (2004, May 27). Chapter 72: A History of Record Covers. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/music/inside/cron.html

- Temple, J. (2015). BU++ER - LUV LOVE ME [Youtube comment]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/v4s1xnKAEBY

- The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). URL. Retrieved from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/URL

- The History of Sound Recording. (n.d.). First Phonographs and Graphophones, and then Gramophones. Retrieved from http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/phono_technology4.php

- Turrell, J. (n.d.). Celestial Vault [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.stroom.nl/nl/kor/project.php?pr_id=4616026

- Vd Velden, D., & Kruk, V. (2015, December 04). Notes for Joeri "Torus" [Letter]. Retrieved from -

- Wikipedia. (2005, March 17). Internet Meme. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_meme

- Wikipedia. (2009, September 9). iTunes LP. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes_LP

- Wikipedia. (2013, February 27). DatPiff. Retrieved March 03, 2015, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DatPiff

- Willson, S. (2015, November 30). An album is being released on Nintendo Famicom cartridge. Retrieved from http://www.factmag.com/2015/11/30/nintendo-famicom-cartridge-chiptune-album/

- Willson, S. (2015, December 01). PAN to release “virtual ecosystem” from Aaron David Ross. Retrieved from http://www.factmag.com/2015/12/01/aaron-david-ross-deceptionista-pan/

- Wilson, S. (2015, November 12). Oneohtrix Point Never unpicks the secrets of Garden Of Delete. Retrieved from http://www.factmag.com/2015/11/12/oneohtrix-point-never-garden-of-delete-interview/

Figure 1

Figure 1 - A famous Winamp skin mimicking physical shape of a stereo sound installation.

Figure 2

Figure 2 – The first designed album cover. “Smash Song Hits by Rodgers & Hart”, by Alex Steinweiss, 1939.

Figure 3

Figure 3 - "Artificial Intelligence volume 1", Released by WARP, 1993.

Figure 4

Figure 4 - The cover image of the "Very excited to announce that..." facebook group.

Figure 5

Figure 5 - Holly Herndon Live A/V, 2015.

Figure 6

Figure 6 - SAGA v1.0, Mat Dryhurst, 2015.

Figure 7

Figure 7 - "8 BIT MUSIC POWER", FAMICOM Cartridge, 2015.

Figure 8

Figure 8 - "Virtual Ecosystem", ADR, Released by PAN, 2015.

Figure 9

Figure 9 - James Turrell’s Celestial Vault, Kijkduin, Den Haag.

Figure 10

Figure 10 - A picture of the green Aphex Twin blimp flying between the London clouds.

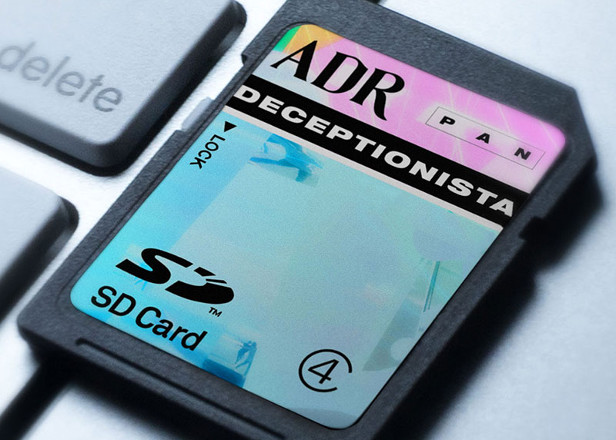

Figure 11

Figure 11 - Photo shot at Evian Christ's Trance Party, 2015.

If you want to experience the thesis "UR SCREEN AS MY ALBUM COVER" written and coded by Joeri Woudstra please type this URL in on your computer: http://kabk.github.io/govt-theses-16-joeri-woudstra-embracing-new-technology-in-musics-visual-cuture/

Figure 1 - A famous Winamp skin mimicking physical shape of a stereo sound installation.

Figure 1 - A famous Winamp skin mimicking physical shape of a stereo sound installation. Figure 2 – The first designed album cover. “Smash Song Hits by Rodgers & Hart”, by Alex Steinweiss, 1939.

Figure 2 – The first designed album cover. “Smash Song Hits by Rodgers & Hart”, by Alex Steinweiss, 1939. Figure 3 - "Artificial Intelligence volume 1", Released by WARP, 1993.

Figure 3 - "Artificial Intelligence volume 1", Released by WARP, 1993. Figure 4 - The cover image of the "Very excited to announce that..." facebook group.

Figure 4 - The cover image of the "Very excited to announce that..." facebook group. Figure 5 - Holly Herndon Live A/V, 2015.

Figure 5 - Holly Herndon Live A/V, 2015. Figure 6 - SAGA v1.0, Mat Dryhurst, 2015.

Figure 6 - SAGA v1.0, Mat Dryhurst, 2015. Figure 7 - "8 BIT MUSIC POWER", FAMICOM Cartridge, 2015.

Figure 7 - "8 BIT MUSIC POWER", FAMICOM Cartridge, 2015. Figure 8 - "Virtual Ecosystem", ADR, Released by PAN, 2015.

Figure 8 - "Virtual Ecosystem", ADR, Released by PAN, 2015. Figure 9 - James Turrell’s Celestial Vault, Kijkduin, Den Haag.

Figure 9 - James Turrell’s Celestial Vault, Kijkduin, Den Haag. Figure 10 - A picture of the green Aphex Twin blimp flying between the London clouds.

Figure 10 - A picture of the green Aphex Twin blimp flying between the London clouds. Figure 11 - Photo shot at Evian Christ's Trance Party, 2015.

Figure 11 - Photo shot at Evian Christ's Trance Party, 2015.