A commonly held view is that there are divisions within disciplines and studies, applied science and arts, technical and humanitarian approaches. The result is an ‘interdisciplinary blindness’, when specialists work with narrow fields, so particularly oriented on one problem or question that the evaluation of something interdisciplinary becomes an assignment for a group of people and the process is not viewed as a whole anymore, but is being divided in many pieces for examination. This approach often creates successful, though very specific views of any phenomena studied. With regard to development of contemporary technology, disciplines intertwine and the world becomes more ambiguous and opaque, when it comes to definitions. More and more things merge into one and it is harder to assign categories. In the art sphere this process becomes visible through the appearance and the rapid increase in value of such terms as multimedia, interactive multimedia, mixed media, hypermedia. Thus we should take notice that interdisciplinarity as a phenomenon has all rights to be treated not as a new tendency, but as a full scale process, that embraces not just the creative sphere, but many more. Interdisciplinarity occurs as a result of the merging of two or more disciplines, that used to be autonomous and separated by the rules, traditions and technologies of a particular genre and previous epoques. These separations have collapsed in our coreless shifting postmodernist world.

Most importantly, in this thesis I am zooming in on the merging of linguistics, literature, art in general and graphic design in particular into one interdisciplinary metagenre, which is a form of expression, that takes place simultaneously in several spheres of art: literature, music, visual art, sculpture, etc. and reflects the feelings and tendencies of today.

In earlier times structuralists considered that the principles of the systematizing of information are axiomatic, normative and over all constant. However, the humanitarian paradigm of the second half of the 20th century shows that these principles possess a rather conditional character. The poststructuralist approach to them will be set apart in this thesis by addressing the works of Jan Jacques Rousseau, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze, Pierre-Félix Guattari and Jean-Franaois Lyotard. Previously, stucturalistic approach created strict classifications and divisions between genres and spheres of media. It has changed nowadays and the world is understood differently: everything may vary and alterate, depending on a recipient (a subject, who receives and reacts to a message, addressed to him). The introduction of the World Wide Web has created a playground and a possibility for multimedia implementation and the direct participation of a viewer in a creative process. This development is a graphic demonstration of a shift in social consciousness, that is visible in both the analogue and the digital worlds. I am referencing the works of Marschall Mcluhan, discussing his theory of typographic man, which explains how following cultural and technical developments influence social processes, focusing on creative fields of language, literature and visual art. Supposing this reasoning is correct, interdisciplinarity becomes an integral part of our development and demands a definition of the metagenre.

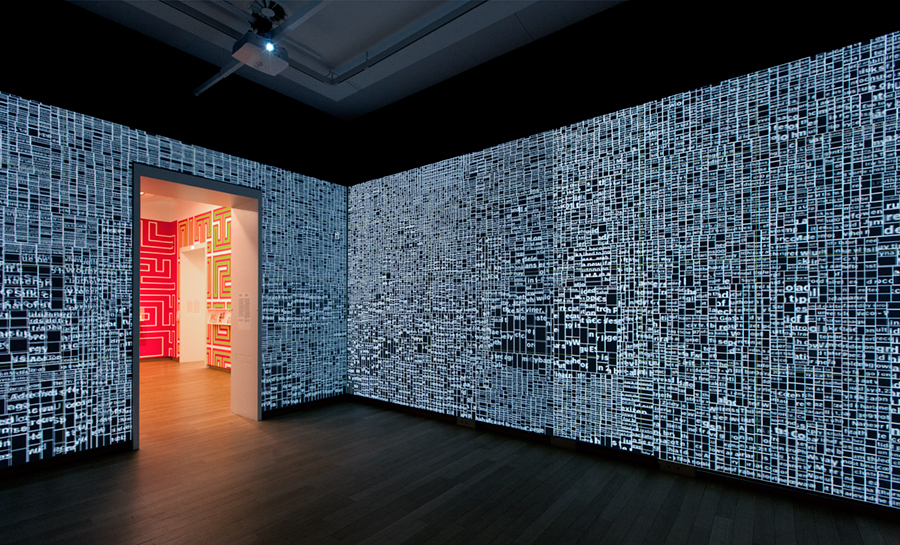

In the first part of the thesis, I describe what a modern metagenre is. My reasoning follows the poststructuralist theory of language and literature to show that they can be applied to analyze the visual arts, uniting those disciplines in one. Through the prism of such notions as hypertext and rhizome that are a way of information organization in this case, seeing the world through language and interpretations, I address its expression in visual arts. Here hypertext represents a type of information (embracing verbal and non-verbal one) and rhizome – the way of a hypertext structure. When it comes to the hypertext, people tend to divide into two groups: whose who know the term from the technological scientific point of view and those who approach hypertext linguistically.

As George P. Landow wittily noticed, one of the most important parallels between computer hypertext and critical theory is that ‘critical theory promises to theorize hypertext and hypertext promises to embody and thereby test the aspects of theory, particularly that concerning textuality, narrative and the roles or functions of a reader and writer’. I am naming both, as I see the unity of these definitions as an integral part for the understanding of the concept of the term. All in all, these are just two different approaches to describe the same thing in a different form: analogue and digital.

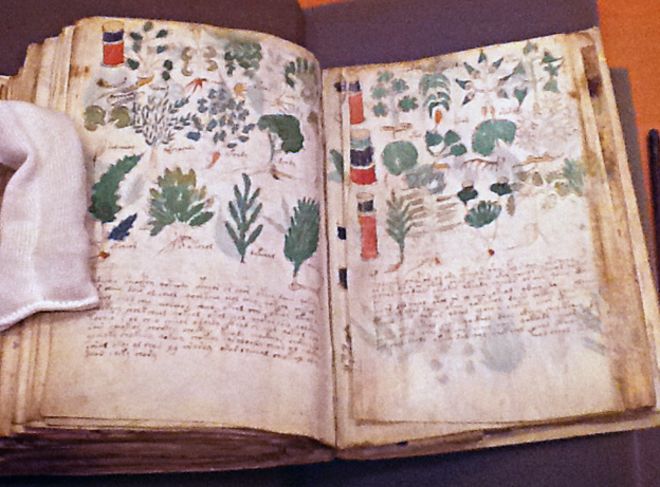

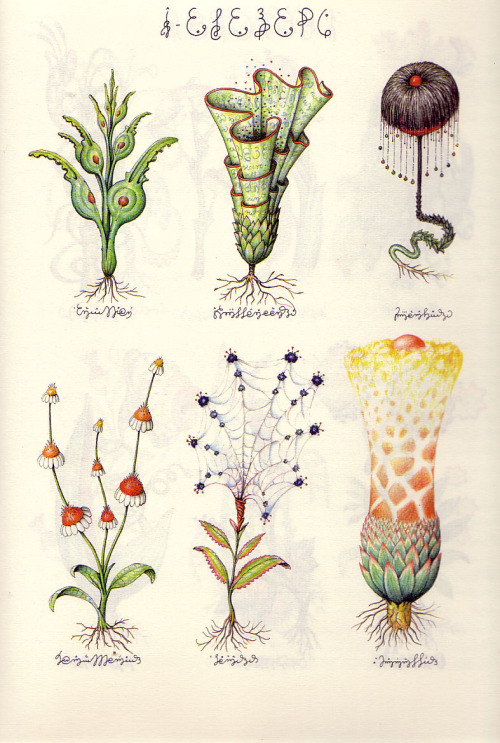

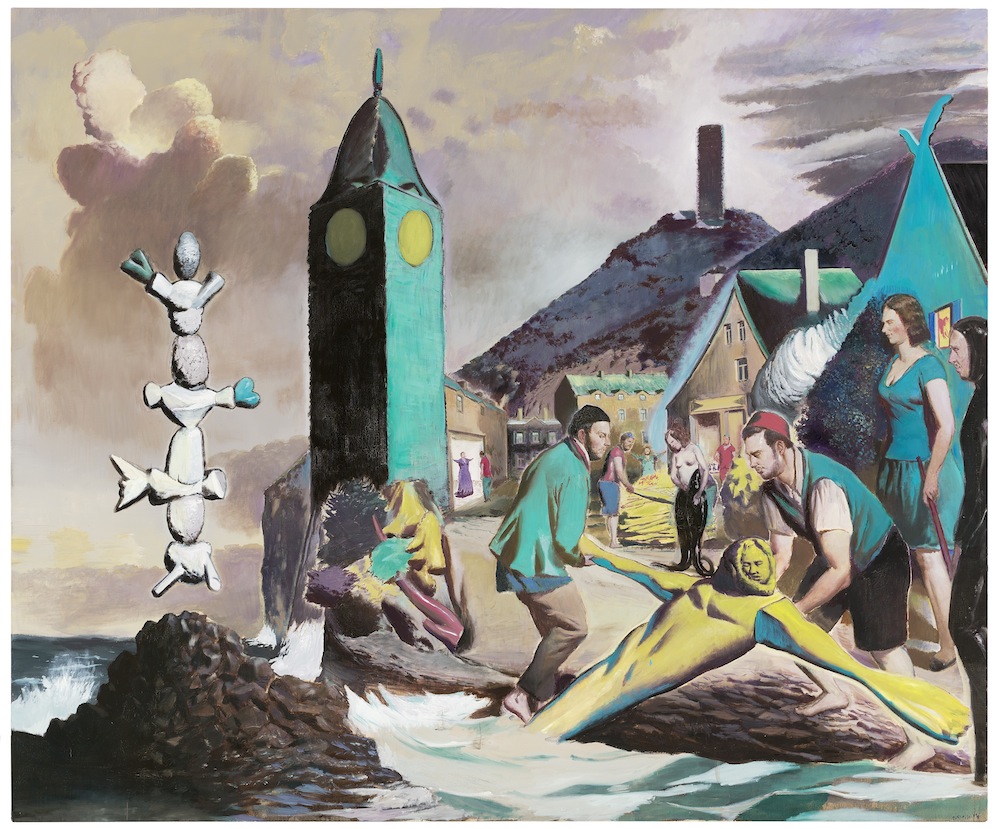

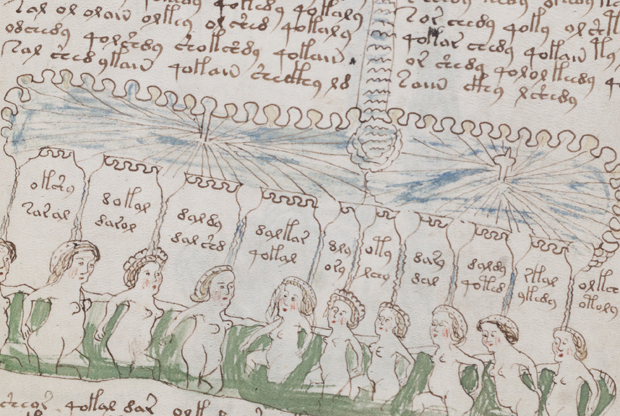

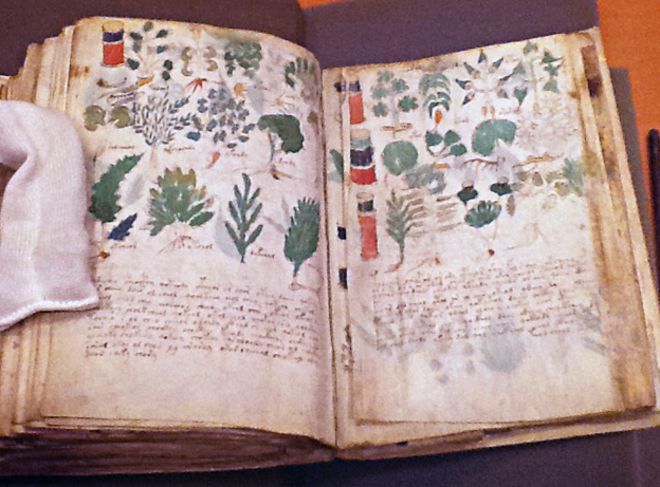

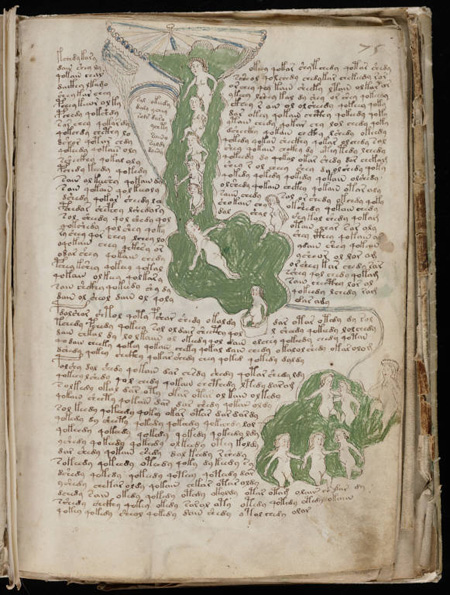

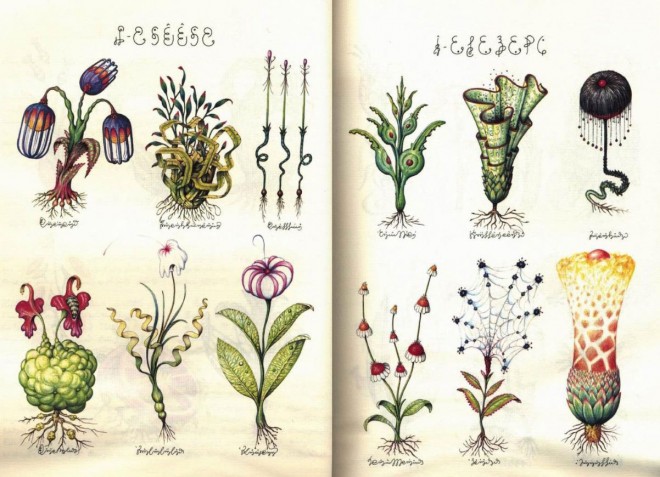

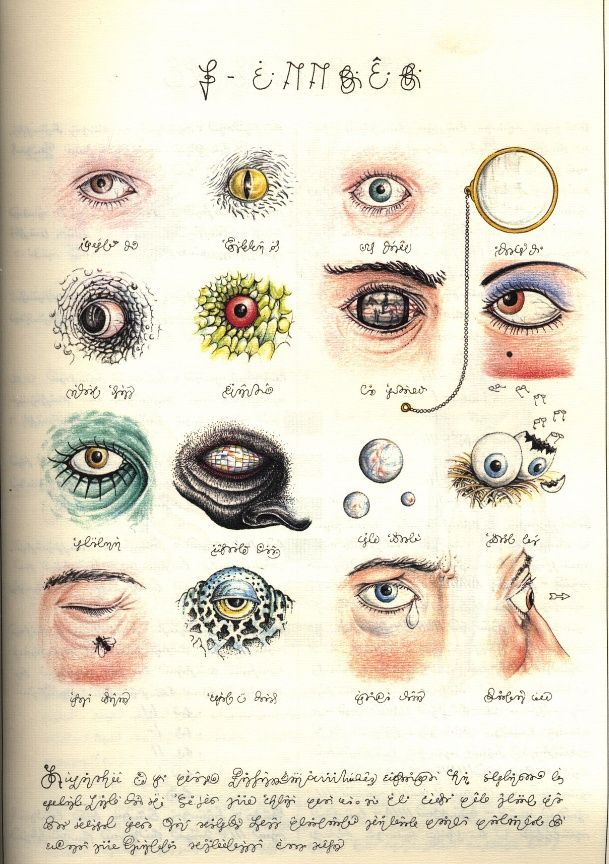

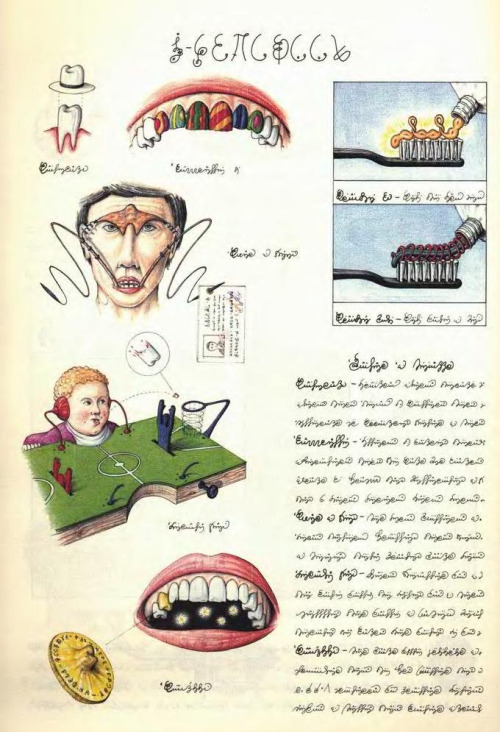

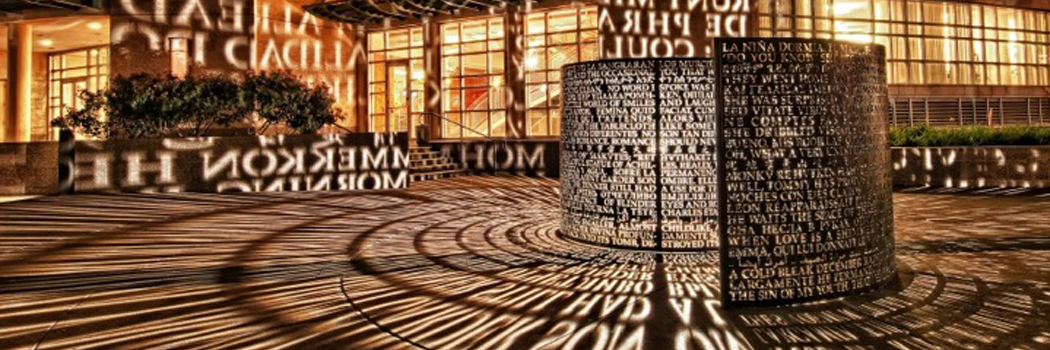

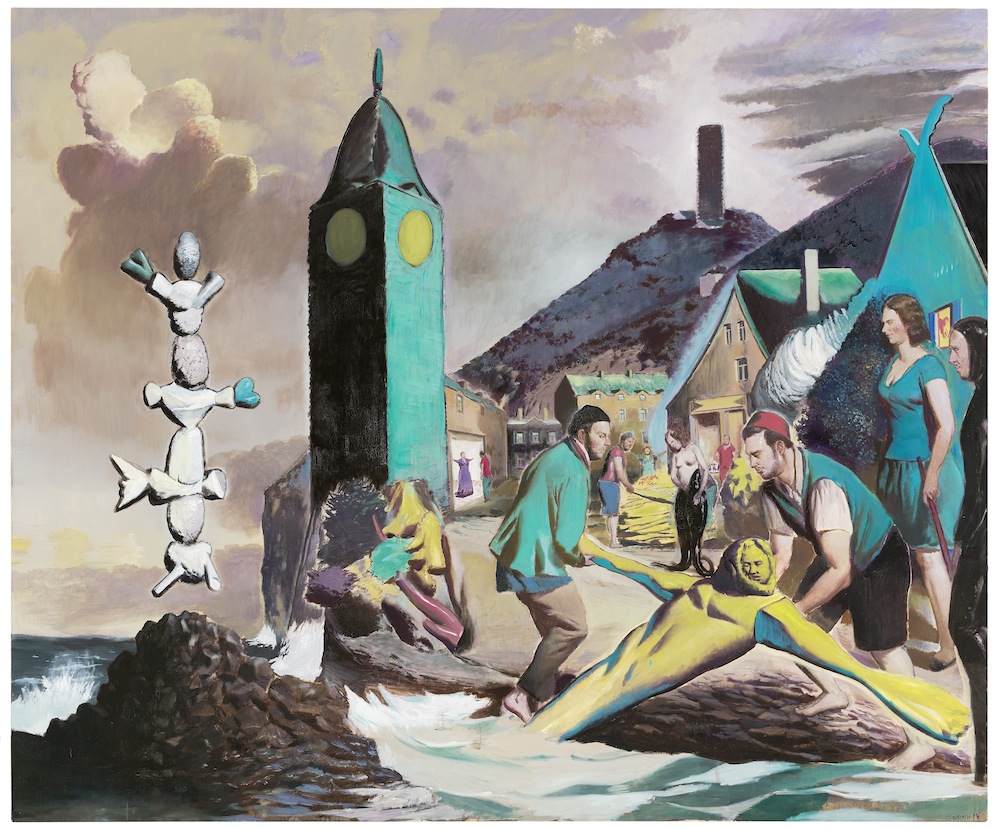

In the second part I examine interdisciplinarity and its existent examples. I have a closer look at the interdisciplinarity of language sciences and visual arts, by analyzing the following works: Voynich Manuscript, ‘Kryptos’ by Jim Sanborn, works by Neo Rauch and I will especially concentrate on the ‘Codex Serafinianus’ by Luigi Seraphini, as an example of a metagenre. All the named works, and many more that I haven’t mentioned, in my mind, represent a certain shift in the approach to art itself.

The immense explosion of new technology and the opportunities that followed it, erased the lines in media separation. The media world today is far more complex then it used to be. Disciplines keep on merging. Creative professionals will have to work in multidiscipline teams to make progress. The media boom has also broadened up the definition of art, freeing it from the limitations of genres and canons, creating one metagenre for the whole epoque and allowing a recipient to actualise connections between the elements of a work and participate in creative processes. The very way of modern thinking is shifting, becoming fragmented: understanding of order has changed and getting from one way to another in a linear way seems inefficient. As it was mentioned in the book the ‘Fantasies of the Library’, where Anna-Sophie Springer develops her theory on the ‘paginated mind’, we have to reimagine the relations between research, discipline, and creativity.’ And it could not have happened in any other age, than in the age of hypertext and fragmented thinking we are experiencing right now. The question is: how to approach and deal with these works?

Next, I make a conclusion out of the analysis and describe the a metagenre with an ascent on its dominant features. I elaborate on what shape could it take in the world of a rapidly developing technology, what place does it take in a graphic design world and what is possible to learn and discover from this type of information organization.