The history of the IS is very close to Al-Qaeda’s one. Being at first one of its branches, the IS took progressively distance with its parent organization for finally cutting all ties with it

(1). In fact, in February 2014, Al-Qaeda described the IS as being a brutal and intractable group. Therefore, in terms of strategy, the two groups have very different ways of proceeding: recreating a caliphate as being a pure islamic state was also Osama bin Laden’s greatest dream, but what Al-Qaeda was trying to build in years, the impatient IS wants to create in an instant. By proclaming the caliphate in June, the IS has been overshadowing Al-Qaeda and gathering a brand new jihadist generation who got spread out after the assassinate of Bin Laden and who were looking for a new spiritual home. (2) Engaged in an ethnic cleansing, the IS has been developping a strategy consisting in first: «purifying» the islamic state and second: expanding to the rest of the world. Unlike its predecessor who had different targets at the same time, the IS wants to show that it is following a clear goal, with a well-thought strategy that nobody can stop. Indeed, the division between Al-Qaeda and the IS can basically be compared to a conflict of generations: a dusty Al-Qaeda believing in a kind of «traditionnal» terrorism and a young dynamic IS breaking every rules. This generation gap finds its best illustration in the way the two groups have been settling their communication strategy and mainly their visual propaganda.

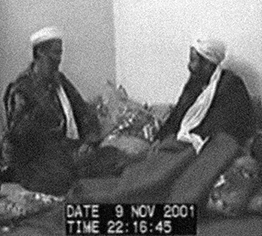

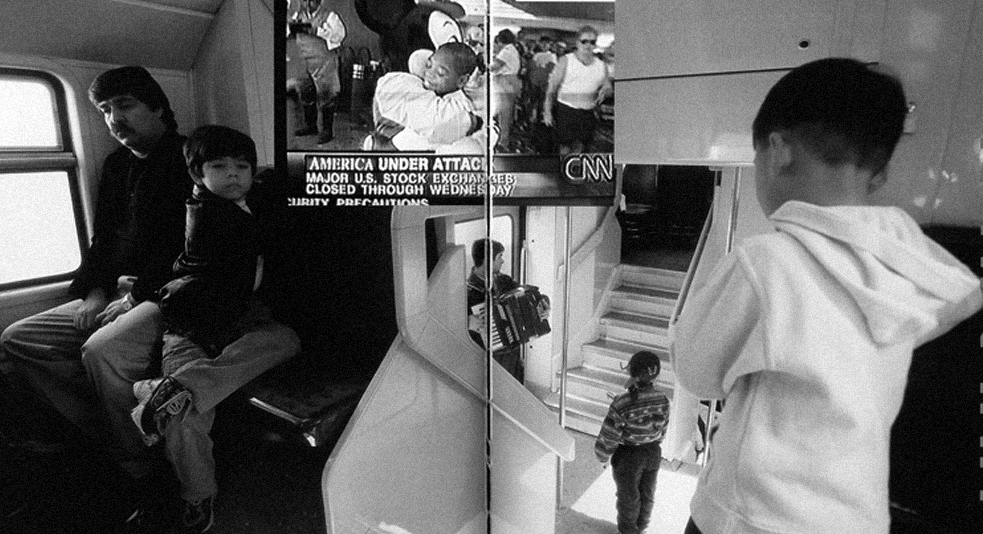

From the very first moments, islamist groups have been using visual propaganda in order to broadcast their convictions, to claim the ownership of an attack and above all, to get an international recognition. It is difficult to know when has been released the first islamist video, but what is sure is that its first main push happened with the 11th of September attacks in America. Bin Laden, as being Al-Qaeda’s leader at that time, released a few audio and rapidly video documents in which he claimed the paternity of the attacks. A video released on the 9th of November 2011 is considered as being the first Al-Qaeda’s video.

During about 9 minutes, the video is showing Bin Laden and a few of his «collegues» talking and laughing about the attacks. The quality of the video is pretty bad: shot in a square frame, the video displays on the bottom the date and time of the film in a 90’s style that was already a bit outdated in 2001.

The camera appears to be standing on a tripod and the only effects that are rythming the whole movie are a few zoom-in/zoom-out on the faces of the different protagonists. Putting this video out of its context (if possible), the film is not really different from a hand-made family movie that could be shot for any gathering event. It almost looks difficult to believe that those smiling men, quietly sitting on pillows, actually planned an attack that killed around 3000 persons. What can however catch consideration is the attention that has been put to attach english subtitles to the video; these

are the very beginnings of an internationalisation of the propaganda that the IS will later push to its extreme. Over the years, the «style» of Al-Qaeda’s videos has never really changed: most of the time they are being shot in a sort of minimalism, displaying one of the main leaders standing in front of a beige background, face to camera, making new declarations and threats. The IS’ videos are light years away from Al-Qaeda’s ones. It’s almost as if the IS looked at Al-Qaeda’s blured, dull camcorder sermons of a decade ago and concluded that extremist Islam really needed a fresh and energetic renewal. If the first IS’ video is sort of following the tradition of men standing face to the camera and making declarations, the whole setting around it completely changed. The video starts with photoshoped images of fighters, the backgrounds are now different exterior scenes,

the fighters pictures appear in a slow motion effect and type is hierarchised, directly included in the video. Far from Al-Qaeda’s english subtitles, the whole video is set in English, from the fighters declarations to the pieces of text accompanying the images.(3)

The evolution of style between the two groups is huge: unlike Al-Qaeda, the IS videos look like they are part of a much wider marketing strategy whose main target is the entire world. Every aspect of their visual propaganda seems to be controlled, with no space for amateuristic mistakes.

The Power of Fascination:

The Islamic State's

propaganda aesthetic

The Islamic State is a relatively young terrorist organisation. Its creation started in 2006, when Al-Qaeda in Irak gathered with 5 other djihadist groups in order to create the Mujahideen Shura Council in Irak. The 29th of June 2014, a caliphate was proclaimed and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was naimed as its caliph. At the time of writing this essay, the group defies all competition as it is turning out to be the most violent and well-funded djihadist organization in history. On August 2014, the IS uploaded a video to Youtube entitled "A Message to America" showing the beheading of American journalist James Foley. Following this savage execution, the islamist group has been releasing other videos in the same gender, attracting really fastly the attention from the international community. Analysing more deeply the IS’ way of communicating, it appears that those brutal videos are actually just a small part of a much bigger communication strategy, consisting in designing films, magazines and games in order to promote the group’s identity. Thanks to an accurate knowledge of Western societies, the IS is attracting fighters from all over the world by producing high quality visuals based on the plagiarism of Western cultural codes. Thomas Hegghammer, director of terrorism research at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment declared in an interview with journalist Joshua Holland:

«We’re probably talking about around 3,000 people from North America, Europe and Australia. In fact, there are more foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq today than the combined number in all previous conflicts combined. So it’s a really extraordinary situation».

The thesis is going to investigate the means of the IS’ visual propaganda by following this research question:

How does the Islamic State's propaganda aesthetic manage to fascinate the western world?

A clear way of seeing the importance of control that the IS is putting on its image is by analysing how the image of the leader is being used. The new caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi became in a very short period sort of the new Osama bin Laden of our time. But unlike Bin Laden who was present almost in every Al-Qaeda’s videos, Baghdadi is nowhere to be seen. Only two pictures and the video of the caliphat declaration can be found of him while he’s the first djihadist leader to control this amount of fighters. When Bin Laden was acting like a

«pop-star» leader

often talking alone in his videos, Baghdadi almost doesn’t talk at all, only a few audio messages appear to be from him (4). Baghdadi is cultivating his image of an

«invisible djihadist»

with only his cruelty talking for him. This silence and absence participate in reinforcing the myth of his personnality. Actually, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is giving a great attention to the control of his image, being totally aware of the power of a communication strategy. The difference between the two leaders’ behaviours finds its best illustration in the visuals that are being produced:

Al-Qaeda’s visuals were about

declaring

whereas IS’ visuals are about

showing.

The IS takes a great effort in producing striking images that have a value of testimony, giving an «inside glimpse» of how sanguinary can IS members be, putting the viewer into the «intimacy» of a tragic scene. Most of the IS’ execution pictures follow a manichean division in the way they are constructed: on one side the IS murderers, standing and using their guns, are creating strong dark vertical lines in the pictures.

On the other side, the victims are very often lying on the ground in an horizontal position. It is interesting to notice that the way the IS is showing power by its images is actually quite simple, a basic opposition between power and prostration, one standing, one lying.

However, a precise analysis of those images made by Tungstène (a software analysing mathematic structures of pictures) reveals that those images have been scrupulously edited. (5) Many areas where dust and smoke are the most visible have been edited several times. This could have happen for different purposes, the simpliest one would be that the members wanted to hide something from the pictures, but it is more probable that those transformations are intended to reveal more dead bodies previously hidden by the dust. On other pictures, the victims blood has been altered: the color has been saturated and the shapes of the pools underneath the victim’s heads have been modified, probably in order to make it visually more present.(6) From a technical point of view, those manipulations are quite classic, even a bit rudimentary as it is basically about blurring and reproducing parts of a picture, everyone in the possession of a basic photo editing software would be able to obtain similar results.

But speaking more generally, it is obvious that the decisions of making changes are all tending to increase the shocking elements. It is also noticeable that the IS’ images have a sort of evenness in their graphical aspects, since all of them are in a rather good quality.

This aspect denounces the possession of a technical knowledge, no matter how big or small. Most of all, it points out an awareness from the militants of what to increase in order to efficiently convey a message. The IS’ execution images are intented to be seen by the world so they have to make a clear point and to communicate with a language that everybody can understand. As a matter of fact, the IS’ visual propaganda aims at triggering fear. First, to the whole Muslim community who is being threatened of a cruel death if refusing to pay allegeance to the Islamic State. Then, to the rest of the world, automatically considered as unfaithfull. However, the IS faces a important problem: the possibility of growing and keeping alive a sanguinary reputation implies to recruit fighters from abroad. In order to swell its ranks, the group needs to attract probable fighters from all over the world and, most of all, to develop a language that can universally seduce people and mainly young men.(7) The IS’ answer to that problem has been to develop a language modeled on westerns brands’ strategies and on products of mass culture:

blockbusters, games and magazines among others.

In May 2014, the IS established its own media branch called

whose main purpose is to distribute diverse materials in several languages. According to MEMRI (Middle East Media Research Institute), Al-Hayat

«is thought to be an initiative of Abu Talha Al Almani, a former German rapper also known as Deso Dogg, who left Europe to fight alongside the IS».(8)

If proved as true, it is very probable that Al Almani implemented his knowledge of the western cultures into the development of the IS’ propaganda. In fact, the uncommon aspect of the group’s communication is that a big part of it aims at an audience culturally different. Thanks to the development of Al-Hayat, the IS can recruit more western people who can add to the IS’ database a precious knowledge about how to target more efficiently the western population. Furthermore, thanks to its media arm, the IS is able to create and transmit its own content.

The logo of Al-Hayat is featured on every media productions made by the organisation, attesting the paternity of the content but also adding a sort of institutionalism to what is being broadcasted. The logo, a 3D golden arabic inscription, is strangely close to the one of the Qatari TV channel Al Jazeera, famous for broadcasting Al-Qaeda’s videos in the past decades.

Appart from the movie Flames of War (analysed later in the Chapter II), Al-Hayat has been distributing smaller videos, subtitles for existing videos, articles, news reports but also magazines and video series. The variety of those productions is clearly reminiscent from commercial strategies. What comes instantly in mind as a comparison is the example of the release of a western blockbuster: quickly after reaching the theatres, all sorts of derivated products are being produced, from mugs to video games, and sold to hooked fans.

«The Potter films are global blockbusters, and Potter video games are spun off from the films. Lego developps Potter-themed-sets. Clothing companies sell Potter t-shirts, nightgowns, and pants. Candy manufacturers sell candy copies of snacks that appear in the film, including Bertie Bott’s Every Flavour Beans and Chocolate Frogs.»

Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization,Tanner Mirrlees.

The IS is completely following this path by merchandising its identity to attract potential combatants. Since the establishment of the Al-Hayat Media Center, the IS has been releasing a campaign circulating on Youtube called «Mujatweets».

This campaign is mainly targeting young people from western countries and showing how apparently great is the life under the obedience of the Islamic State (9). One of its episode (most of them have been deleted from Youtube), is depicting an IS member visiting injured fighters in a hospital and offering them comforting and encouraging words. Another «Mujatweets» video shows smiling IS members handing out candy and ice cream to cheering children. The production of this video serie is also in itself playing with western cultural codes and their history since the premices of TV series started in the United States in the 20th century.

However, those more politically correct messages transmitted in the «Mujatweets» give a paradoxal «normal» image of the IS fighters,

suddendly acting

like any other human being.

If brutality catches attention from the world, a kind behaviour can attract, giving the impression that behind the crimes a noble pursuit is being fulfilled. Furthermore, by showing a more ordinary behaviour, the group is also silently implying that everybody can become an IS’ fighter and, as soon as being part of it, can integrate a nice and fraternal community.

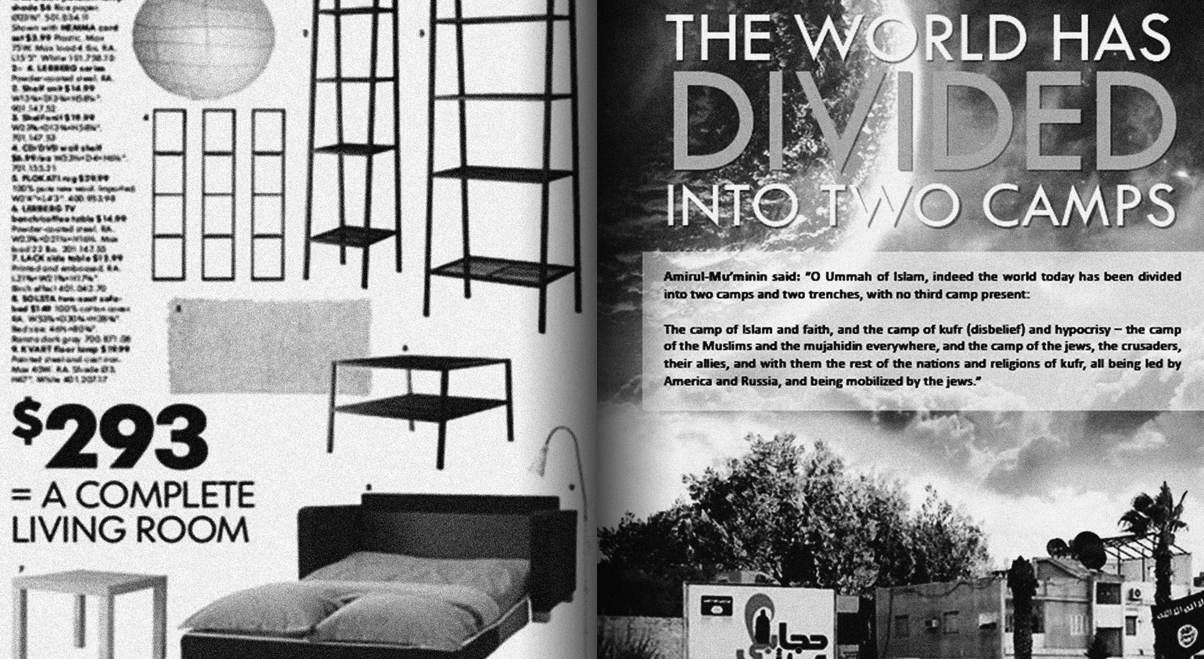

Besides trying to captivate its audience with a supposed kindness, the IS is also creating some «goodies» that people can purchase or download. One of them is an online magazine called «Dabiq» (10), first published in July 2014, in different languages including English. The layout of the magazine could be the one of any western magazine: a graphic guideline is being respected within the different issues and all the texts are set in the sans-serif typeface Futura which is, in the western world, one of the most used typefaces in the visual landscape.

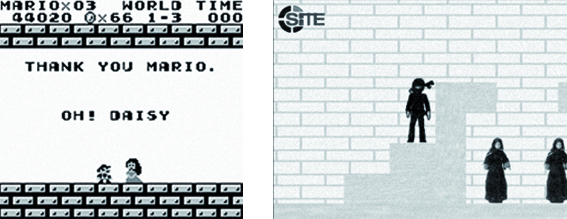

Another product that can be added to this collection is a serie of HTML5 little games available on the web.(11) If the design of those games stays quite basic and even a bit childish, their purpose is to play the war in the comfort of a living room. Thus, as seen from the start, the IS’ propaganda strategy made a giant step from Al-Qaeda’s one. Profiting from its recruits’ knowledge of western cultural codes, the group is developing a propaganda aesthetic that uses all of the tools of its digital era. Using Internet, social media, video games and movies among others, the IS is fascinating people from all over the world by giving an impression of an oversized movement, present everywhere, that turns fiction into reality.

Films, series, magazines… The IS’ propaganda panoply is particularly wide, using all of the tools that are available in 2014: Internet as being its best ally. When, for instance, the Nazis were using flyers and radio emmissions in 1940, the IS is Tweeting, posting videos on Youtube and photos on Instagram.Thanks to Internet, the IS can independantly flood the world with its images and promote its actions without interruptions, constantly uploading new content. Since the summer 2014, the IS members became present on social media, creating their official pages on Facebook and Twitter where they can gather a great amount of followers from all over the world. Robert Hannigan, head of Britain’s surveillance agency, recently said that:

«a new generation of freely available technology has helped groups like Islamic State (Isis) to hide from the security services».(12)

In fact, the democratisation of technologies have considerably facilitated the IS’ terrible soaring. Numerous militants who left their countries (and mainly western countries) to join the IS are not only becoming fighters but also playing a very important role in the IS’ propaganda.

Those militants use their social media accounts in order to post images showing a supposed good life as being an IS’ fighter. Several of those posts show activists coming to join the IS and actually recreating their western standards of living on the site.(13) Joining the IS doesn’t necessarly mean to accomodate to really severe amenities but rather to obtain a comfortable standard of living, maybe even better than the one back home…

Pictures of new houses and cars that got obtained after the expatriation in Irak are targetting a population struggling in its daily life, who can easily be seduced by the idea of improving its level of life. Other pictures showing pizzas, candys and bathing in a swimming pool are all apparent proofs of a better life welcoming those who would join the movement. If no informations can be found yet about the number of people designing the official IS propaganda, it is definitely possible than only a few people with laptops and an internet connexion could have done the job.As an IS suppoter said, interviewed by VICE news:

«There are a lot of people in Isis who are good at Adobe applications – InDesign, Photoshop, you name it. There are people who have had a professional career in graphic design, and [others] who are self-learnt.».

Indeed, the development of technologies has been making everybody able to create simple images and to spread them around the world thanks to the social media. Steve Rose, reporter at The Guardian, exactly describes this effect:

«Ironically, the beneficiaries of this media democratisation are a medieval theocracy hell-bent on eradicating democracy from the face of the earth.» (14)

The IS strongly beneficiates from this democratisation, given the fact that another part of its propaganda is actually made by militants who stayed in their home countries and actively show sympathy for the movement by regularly posting messages or hand-made propaganda images on the web. This activity on the web maintains the visibilty of the IS and gives a feeling of a worldspread’s community, being encouraged by each others’ posts in continuing the media battle. Once again, the visuals created by those «independants» participate in giving a more accurate internationalisation of the propaganda. An example among others is an image posted on Instagram and seemingly appreciated by a western viewership:

«You only die once» reads one image that attracted many likes on Instagram, «Why not make it martyrdom?».

Looking at this image, it is quite difficult to distinct if the photo has actually been shot on the site or if the scene has been extracted from an action movie. This reutilisation of aesthetic codes from western action movies and video games is another string to the IS’ bow, participating in its power to fascinate audiences. The IS is digging into the commonplaces of western’s visual landscape and turn them into powerfull weapons; this strategy found its apotheosis in the release of movies. In June 2014, the first one of the gender was posted on Youtube. Entitled The Clanging Swords IV (confusingly, parts I, II, and III do not exist), the film consisted in edited scenes of battles, with sounds and effects such as slow-motion. The production had every features of an american blockbuster, except its lenght. This difference got quickly overcome in September 2014, when the IS released a 55-minutes English language film called Flames of War.

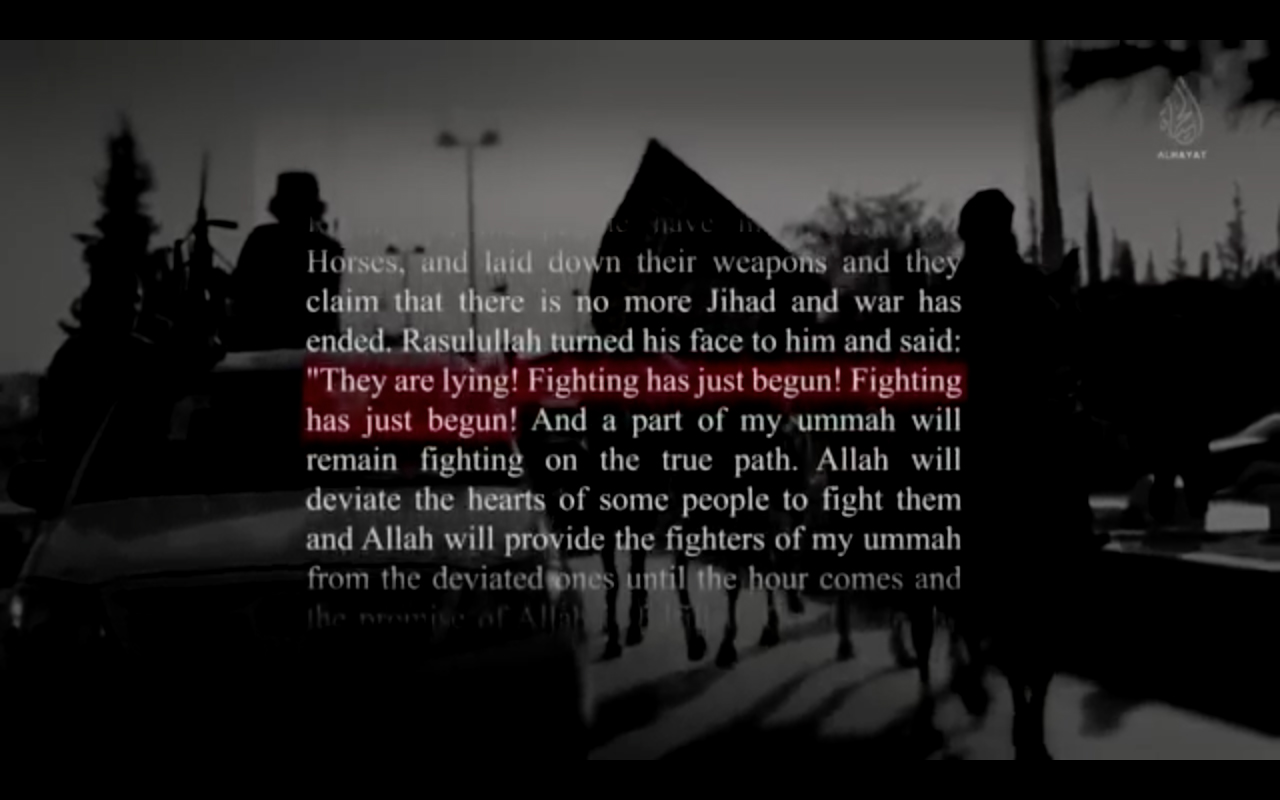

Released in September 2014, the purpose of Flames of War is to explain the IS’s seizure of the Syrian Army (15). The structure of the movie can basically be divided in three main parts. The first one (≈ 8 minutes) is a sort of introduction explaining, with archive images of American presidents and soldiers, the IS’ version of the war’s start. The second one (≈ 34 minutes), is more of an insight into the ground battles, showing explosions, battles, prayers and death. The last one (≈ 13 minutes) consists in the culmination of sanguinary and horror, with group executions and soldiers (apparently) digging their own graves.

What is striking from the very first minutes is the didactic purpose of the movie. Following the footsteps of IS’ communication strategy, the whole movie is accompanied with the english voice of a narrator or, in the case of an arabic one, english subtitles. At the beginning and the end, extracts from the Quran are being displayed, all translated in english while an arabic voice recites it. Following the rythm of the arabic voice, passages of the texts are being highlighted, allowing non-arabic speakers to make a relation between what they read and what they hear, and yet to feel closer to what is being said and, probably, to learn some parts of the text.

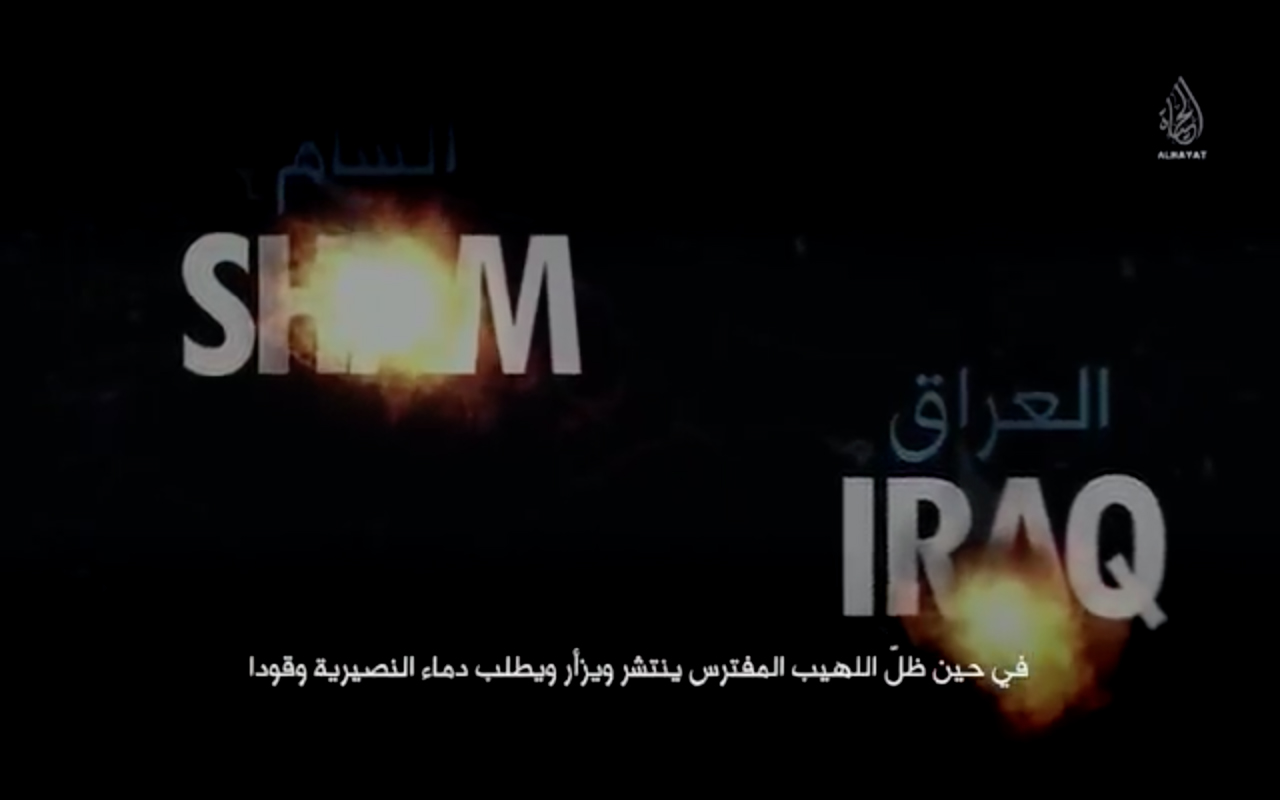

Another feature of the movie is the use of maps that are illustrating the talk.

The first one appearing is basically showing the geographical situation of Irak and Sham (the region of Syria) whose names are displayed in a white sans-serif typeface accompagnied with the arabic translation in a light blue.

A fire burning in the middle of the names makes clear that these are countries where battles occur. From a graphical point of view, this already shows a bit of a

knowledge; even simple, I doubt my mother would be able to do that. Another map is showing conflicts and two big arrows are describing the moves made by the fighters. This second map is using the same «graphic line» as the previous one and attests that a reflexion has been made about how to design and make things understandable. Appart from clearly explaining issues, Flames of War is also excelling in terms of using blockbusters effects. From bazooka fires to processions in the streets, the movie is rythmed by an alternation between live actions and slow motion effects that create an aura around these specific moments. The use of this effect is reminiscent of action films, where it is being used for dramatic effects such as the famous bullet-dodging effect, popularized by The Matrix. In opposition to the slow-motion, Flames of War also uses a lot of accumulation of action sequences that are fastly being displayed one after another. This results in dynamic sequences where the jihadists are turning into heros, being on all fronts and showing no mercy for their opponents.

In the same way, transitions betweensequences are often being made by a burst of flames, going from the bottom to the top of the image and radically «setting the screen in fire». If the link between those transitions and the title of the movie is far from being subtle, the repetition of this effect at some key moments of the film still participates in putting the movie in the action gender.

Finally, other details such as different camera angles, the raising of the volume for jihadist songs and the evenness of the light color in the sequences are all proofs that behind this movie, people with editing skills have been working and searching for the best effect.

To sum up Flames of War, it is patent that the movie inherits its visual vocabulary from action movies and especially from American blockbusters. Despite some defects like a better structure of the «storyline» (the sequences are somewhat repeating themselves), the movie is visually slick and sophisticated.

Apart from its cruelty scenes, watching Flames of War is disturbing in the sense that it is turning murders scenes in sequences of a movie, making the borders between fiction and reality difficult to grasp. Even the way of designing the title is also very reminiscent of the western popular TV serie Game of Thrones. With a typeface fairly similar, the use of a line in the construction and a title set in three parts:

Flames | of | war strangely sounds like Game | of | Thrones.

«The clash of swords

is the song of the defiant

and the path of fighting

is the path of life

•

between an assault,

that exterminates the tyrants

and a silencer,

with a beautiful echo

•

My religion has been strenghthened

and the tyrants have been humiliated

so rise up, oh my people,

on the path of the brave.

•

For it’s either a life

which delights the guided,

or a death which enrages the enemies

so arise brother,

get up on the path of salvation

so we may march together,

resist the agressors»

•

Nasheed Saleel Al Sawarim

soundtrack of

The Clanging of Swords IV

Throughout its numerous propaganda elements, the IS manages

to fascinate people who are being caught by the highly fictionnal aesthetic of its productions. The IS’ propaganda is aware of the flaws of western societies and gets nourrished by them: the promise of a better life as a reward is an aspect that has already been mentioned.

However, another one is the apparent possibility to realise in

reality what is normally only

possible in fiction.

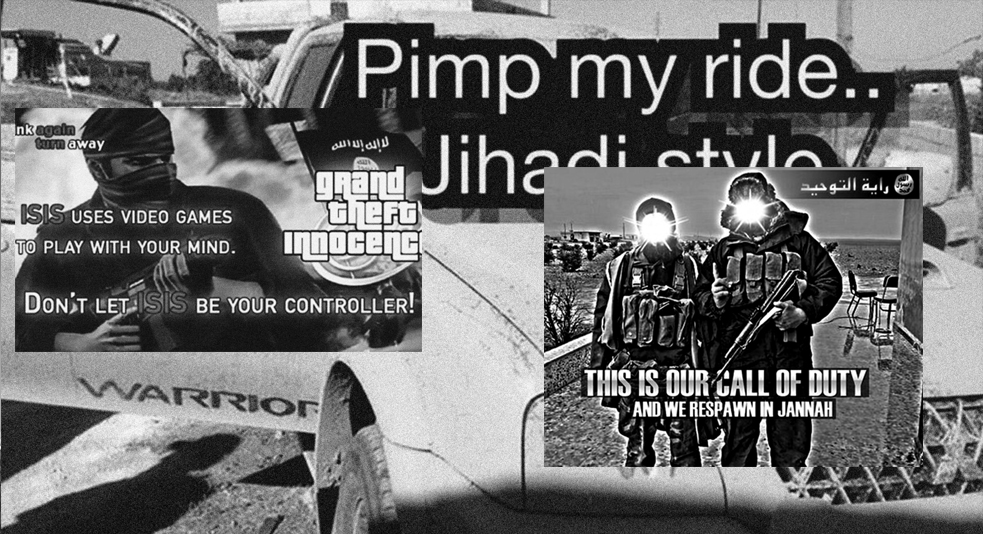

Indeed, a third movie posted on Youtube by the IS made a step further in getting this relationship between fiction and reality even thinner than before. This whole video is only made out of sequences from the famous video game «Grand Theft Auto», showing police officers being gunned down and trucks being blown up.(16)All of the sequences of the video are extracted from the video game, creating confusion for the viewer to define if what he sees is real or fictionnal.

«Your games which are producing from you, we do the same actions in the battlefields.»

The sound, a djihadist song, is the only element that was actually created by the IS. In the same way, an image has been circulating on the web, showing two militants associated with the game «Call of Duty». Those elements, acting in the same way as Flames of War, are transposing the

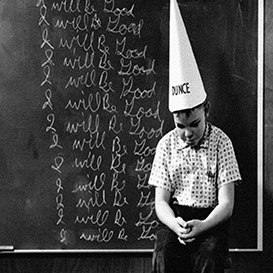

war into the fiction and here, into the game, implying that the IS’ fight is not far from the realisation of a game in real life. If you enjoy playing «Grand Theft Auto», you definitely can become an IS’ fighter. Moreover, with this video, the IS smartly pinpoints a major issue of the current digital era consisting in phenomena such as addiction to technologies and exclusion from the society. The social exclusion due to technologies have been one of the key roots of many contemporary urban problems. Affordable computers and Internet connexions have lead to the development of new social behaviours based on the reduction of direct human interactions: the screen has being a new buffer zone between individuals.(17) The IS’ propaganda is precisely operating in this field by implementing fiction in its real battles and profiting of a western new «desease»: the addiction to Internet, computers, and video games. Apparently, joining the IS would permit to quit a digital life lived by procuration since participating in the ground battles seems to offer the possibility to embody one’s favorite film’s or video game’s character. Taking part in the IS’ battles resembles to give a new meaning to one’s life that had previously been lost with the use of technologies.

It is interesting to notice that some reactions among the western countries have been to consider the whole IS events has a complot theory headed by the United States. One of the main arguments serving the theory is actually based on the quality of the IS’ visuals, some westerners can hardly believe that a community from the Middle East can possess this awareness of western codes, master technologies and use editing skills. Among other posts, the one of an American woman on her blog is a good illustration:

When the IS is «selling» his actions by using fiction, a part of the western world is actually asking for it, refusing to accept the possibility of a terrorist group being able to manipulate western societies. In reaction to the departure of some citizens to join the IS in Irak, the United States have been launching a «counter media attack» in the form of a Twitter page called ThinkAgainTurnAway, whose purpose is to avert people of the danger of joining the IS.

One of its post parodies the IS’ Grand Theft Auto video: «Grand Theft Innocence – don’t let Isis be your controller!» Predictably enough, the IS militants have parodied ThinkAgainTurnAway’s parodies: the media war between the West and the Middle East becoming a hall of mirrors. Ironically, the United States are fighting the IS propaganda by using the same tools (photo editing, social media, videos…) but suprinsingly, they are creating less strong images.

Through many of the examples that have been previoulsy mentioned, it is patent that the IS has been playing with visual codes that are part of western societies’ visual routine. By precisely mimicking films and video games, the IS manages to push forward a fascination developped by western societies for action. By consciously editing its videos, the group turns what is supposed to be real into a fiction where massacres appear

larger than life.

In fact, the appeal from the public for real stories translated in fictions has already been proving its worth: the use of the mention «based on a true story», sometimes displayed at the beginning of a film, is a catcher of attention for an audience used to a daily amount of violence. Watching Flames of War, for instance, places the viewer in a paradoxal situation since the horror is romanced without using actors: the viewer is confronted with watching men in their very desperate last moments. Following an argument raised by the American journalist Natasha Lennard (19):

This concept of «The Uncanny» was developed by Sigmund Freud in 1919. Freud used it in order to describe an instance where something can be both familiar and alien at the same time, resulting in a feeling of uncomfortably strangeness.(20) This situation is quite close to what is happening with the IS’ propaganda aesthetic: the viewer already saw those sequences a hundred times before in action movies and yet, sees them for the very first time. Something that is normally being considered as being part of a (disputable) entertainment is turning into something worrying. Following this theory, the higher level of the uncanny feeling occurs when related to death and cadavers since there are not many others fields in which the human thoughts and sensations have so less changed since the primitive times. Daniel Heischman, Head of the Upper School at St. Albans School in Washington DC, describes in an essay, the contradictory reaction he experienced as watching on the TV the events of the 11th of September 2001 (21):

The testimony of Daniel Heischman highlights two characteristics of the uncanninness that also occur with the IS’ visuals. First, the uncanny easily surprises every time the borders between imagination (fiction or here, dreams) and reality fade out. Indeed, in the realm of fiction, a lot of things don’t trigger the feeling of the uncanny as they would do in real life. Secondly, Daniel Heischman refers to a sort of unexplicable fascination when seeing a dreadful event, a behaviour also happening when watching the IS’ visuals.

According to the Webster’s Dictionary, «fascination» can be compared to a form of witchcraft: «The act of bewitching, or enchanting; the exercise of a powerful or irresistible influence on the affections or passions». It is manifest that under the spell of fascination, people can do things without understanding their reasons and also probably believing messages they previously didn’t agree with. By triggering people’s primitive emotions, the IS garanties to its propaganda an attentive audience. Plato, in the book IV of Republic, already wrote about the inner fascination of the human nature for violence (22):

This story illustrates what the german philiosopher Emmanuel Kant calls the human «double nature», both pathological and intelligible at the same time (23). If a solution to this deep human struggle can’t be found, it is however possible that a better moral but also aesthetical education could permit to stem the effectiveness of propaganda movements such as the IS’ one. Unfortunately, the western mass culture is pointing in another direction.

As confronting the IS’ propaganda with what has already been done in history, it appears that the motivations of the IS are not different from the ones of previous extremist groups. Since ancient civilisations, the manipulation of crowds has always been functionning throughout a conscious use of mass media. The IS is operating in the same turf, playing with what Western societies have been defining as their mass culture. It is however remarkable that very few progess has been made in the capacity from a population

to analyse the codes by which it is being massively entertained.

In fact, the western spoon-feeding mass culture is not asking reflexion from its audience, it keeps on harping the slightly same scenarios to a population hungry for entertainment without complexity. Many of those easy cultural products satisfy primitives emotions: a heroic behaviour from the main character, the use of a particular music at some key moments, a manichean division in the storyline…

None of those features leave a space for the viewer to create a personnal and more reflexive approach to its entertainment. In his book, The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord, french theorist and film-maker, describes the concept of «spectacle» as being the inverted image of society, in which relations between commodities have supplanted relations between people.(24) Debord notes that quality of life is impoverished by a degradation of knowledge with the hindering of critical thought. According to him, the society of spectacle is not providing the entertainment that is previously researched since it doesn’t trigger any action of thinking. In fact, the mass culture consciously draws a line between the passive contemplating (entertainment) and the active thinking (everything else than leasure).

An interesting comment has been made on that subject in the book entitled The age of the dream palace, where Jeffrey Richards (the author) analyses the mechanisms of entertainment. He highlights similarities between cinema and religion quoting Richard Winnington:

Thus, Western modern societies seem to have replaced religion by other means of fascination In the same way as religion has been accused to prevent population from the exercise of its critical thinking, mass entertainment is most likely another threat to reflexion. By implementing this

«spectacle» into its aesthetic, the IS managed to developp an ultra modern propaganda whose codes sneak into the Western visual landscape, beneficiating from the power of fascination that the mass culture has being developping over decades. In this case, an important responsibility is laying in the hands of those who create and design this visual landscape. Steve Rose, reporter at The Guardian (previously mentionned) raises this argument consisting in the fact that:

Actually, a few directors have been reacting to the expansion of the IS’ visual language, pointing up their possible role in the development of such propagandas. American documentary maker Eugene Jarecki declared that:

In the same vein, Joshua Oppenheimer, director of The Act of Killing, also urges the West to reflect upon its own position:

Even if the Western’s mass culture and entertainment industry can’t be seen as responsible for the development of religious extremist movements such as the Islamic State, it is however worrying to observe that they can be used as a

tool to empower

the propaganda of a group whose roots have nothing to do with secular democracies. Such phenomenon raise questions about the role and responsibility of professions who create and design this visual landscape.

To what extent are professionals designing this visual landscape responsible for such phenomena?

Robert Stam, an American specialist in film history, resumes the struggle for film-makers in choosing between critical thinking or passive pleasure in his book Reflexivity in Film and Literature: From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard. According to him, those professions are divided between

It is remarkable that this two contrasting sentiments embody a problem that can certainly be applyed to every profession dealing with

the use of visuals. Indeed, as focusing on the practice of graphic design, a same distinction can be found with either accepting to produce more seductive products in order to serve commercial purposes, or being able to concentrate on a more theoretical and research based practice, probably not financially enough supported. A conversation between design critics Rick Poynor and Michael Rock highlights this problem: (28)

Following this quote, it is manifest that the capitalism structureof the Western world is pressing designers and visual makers in producing visuals whose main prupose is to create a financial rentability. In her thesis entitled Re-envisioning Graphic Design as a Dialogic Practice, Marie-Noëlle Hébert describes the possibility of incorporating «disruption in design», whose purpose is to

awake a critical reflexion from the audience: (29)

According to Marie-Noëlle Hébert, using design in order to interrupt a linear transmission and to introduce unexpected

elements is susceptible to generate reflection both from the user in regards to what is represented, and from practitioners in regards to design’s basic functions and communicative capabilities. In the same idea,Jan van Toorn, a famous dutch graphic designer, has been developping the concept of a «dialogic design», aiming at a communicating in a critical manner (30).Jan van Toorn has been actively animating the debate about the social and cultural responsibility of graphic designers in the Netherlands. Throughout his work, he militates for a process where «both designers and recipients are co-authors of the message», teaching the receivers of its design to become «writerly readers».(31) His work functions as visual enigmas, gathering visuals that have, at first sight, nothing to do with each others.

The viewer is triggered in trying to reconstruct the storyline that has been build behind what he sees. By exercing its reflexion and getting involved in the visuals that are presented to him, the viewer deciphers the world in a new way, looking behind the commonplaces of its daily visual routine and building a better resistance to its visual surroundings. The work of Jan van Toorn is a model of how to get around visual manipulation by giving a better visual education to populations.

Thus, visual makers (film-makers, graphic designers, or others) experiment particularly complex situations since they are financially dependant from the capitalist structure of Western societies. The demand of profitability from the visual industry is dividing designers behaviours between either satisfying a mass audience used to spoon-feeding entertainments, either challenging perceptions and critical reflexions from the viewers. The IS, throughout its propaganda, has demonstrated its accurate awareness of flaws in Western societies by copying codes of mass entertainment but also by beneficiating from the struggle of a profession that can hardly change its current visual landscape.

However, the possibility of developing a better critical involvement from the audience by producing more challenging visuals is an opportunity that needs to be seized. Indeed, as a future professional graphic designer, I feel strongly commited to this process. In my previous works, I have already been having a certain intuition and interest for the research of «disruption» in graphic design, however without being able yet to precisely name this interest. Troughout the production of booklets and videos, I have been increasingly wondering about the power of evocation that images and typography contain, and mostly about how a conscious use of those features can bring the viewer in questionning what he is observing.

Interrupting a continuity,

building visual enigmas that can only be understood by an active and reflexive audience, those are themes that are dear to me and that I wish to explore troughout the research of my Graduation Project.